by Denise Noe

First published in February/March, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Forty-six at the time of the Borden trial, Hosea Morrill Knowlton was born in Durham, Maine on May 20, 1847. He was the eldest son of the Rev. Dr. Isaac Case Knowlton, the pastor of the Universalist Church in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and Mary Smith (Wellington) Knowlton.1

Forty-six at the time of the Borden trial, Hosea Morrill Knowlton was born in Durham, Maine on May 20, 1847. He was the eldest son of the Rev. Dr. Isaac Case Knowlton, the pastor of the Universalist Church in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and Mary Smith (Wellington) Knowlton.1

A devotion to the faith in which he was raised appears to have characterized and defined Hosea Knowlton’s life. He belonged to the Universalist Society from 1872, was superintendent of a Universalist Sunday School for three decades, and acted as church society treasurer.2 The Universalist denomination originated in the eighteenth century and teaches, “it is God’s purpose to save every individual from sin through divine grace revealed in Jesus.”3 The church’s official creed includes the statement, “We believe that holiness and true happiness are inseparably connected, and that believers ought to be careful to maintain order and practice good works; for these things are good and profitable unto men.”4

Hosea Knowlton went to high schools in Maine, New Hampshire and finally Massachusetts. He attended Tufts University from which he graduated in 1867 as salutorian of his class. He later became a trustee of his alma mater, earned a law degree at Harvard, and was admitted to the bar in 1870, practicing law in New Bedford, Massachusetts.5

Knowlton served as a Registrar of Bankruptcy from 1872 to 1878, was on the New Bedford School Committee from 1874 to 1877, and was City Solicitor in 1877. Knowlton served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1876 to 1877. From the House, he won office in the state Senate where he served from 1878 to 1879. He was district attorney of the Southern District of Massachusetts at the time of the Borden murders in 1893 and would remain in that capacity until the following year (194).

Knowlton’s personality was one that was unafraid to try new things. He was noted for being the first lawyer in New Bedford, Massachusetts to employ a stenographer and ride a bicycle (195). Although not much is written about his hobbies, this fondness for bicycle riding may also indicate an interest in exercise and the outdoors.

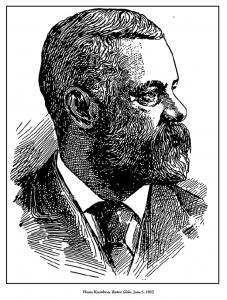

Thoughtfulness and consideration appear to have been some of his other qualities. It was reported that many of his good deeds “were done under the cover of a gruffness that hid a very tender heart.”6 Journalist William M. Emery said of him: “He was ever ready to do a favor for a friend. One day, during a Superior Court session in this city, I sat, as a reporter on guard, in an anteroom, longing for a cigar, and regretting stores were too far distant. Mr. Knowlton did not have a cigar in his pockets, but said, ‘I’ll get you one.’ Going into the courtroom he quickly returned with the desired ‘smoke,’ remarking, ‘I wheedled this off the high sheriff for you.’” Emery goes on to say that when Hosea Knowlton was under stress he “might speak tersely” or even “brusquely” but elaborates that, overall, he possessed a “winning personality.” Knowlton’s grandson, Gen. William Knowlton, described his grandfather’s physical appearance as of “not more than medium height,” and having a “robust figure and impressive presence,” a “deep voice,” with hair and beard a “sandy” color, although he kept himself clean-shaven in the last years of his life.7

Hosea Knowlton was also a music lover. He was first president of the Madrigal Society, a position he held for seventeen years.8 General Knowlton writes, “He had some ability at the piano and would play a polka, and his children and their young friends would dance” and states that he once filled in for an absent organist at the Universalist Church he attended.9

Hosea married Sylvia Bassett Almy in 1873. Sylvia had been a schoolteacher before their marriage. The couple had seven children—four boys and three girls.10

Knowlton’s questioning of Lizzie at the Borden inquest shows him to have been a clear and precise examiner. Yet, his persistence as a questioner is what sets him apart from the average prosecutor. This talent is strikingly illustrated by the following passage from the inquest when he questions Lizzie’s story of having slowly eaten some pears in the barn during the time her father was killed. Knowlton found this tale suspicious.

Q. You were feeling better than you did in the morning?

A. Better than I did the night before.

Q. You were feeling better than you were in the morning?

A. I felt better in the morning than I did the night before.

Q. That is not what I asked you. You were then, when you were in that hot loft, looking out of the window and eating three pears, feeling better, were you not, than you were in the morning when you could not eat any breakfast?

A. I never eat any breakfast.

Q. You did not answer my question, and you will, if I have to put it all day. Were you then when you were eating those three pears in that hot loft, looking out of that closed window, feeling better than you were in the morning when you ate no breakfast?

A. I was feeling well enough to eat the pears.

Q. Were you feeling better than you were in the morning?

A. I don’t think I felt very sick in the morning, only– Yes, I don’t know but I did feel better. As I say, I don’t know whether I ate any breakfast or not, or whether I ate a cookie.

Q. Were you then feeling better than you did in the morning?

A. I don’t know how to answer you, because I told you I felt better in the morning anyway.

Q. Do you understand my question? My question is whether, when you were in the loft of that barn, you were feeling better than you were in the morning when you got up?

A. No, I felt about the same.11

Knowlton apparently took on his most famous case with reluctance. According to David Kent in Forty Whacks, after being informed by the Attorney General of Massachusetts Albert Pillsbury, that he, Knowlton, would be chief prosecutor for the Lizzie Borden case, he wrote to Pillsbury, “Personally, I would like very much to get rid of the trial of the case and fear that my own feelings in that direction may have influenced my better judgment. I feel this all the more upon your not unexpected announcement that the burden of the trial would come upon me.” Later in the same letter Knowlton stated that he did not anticipate a conviction, remarking that, “there is every reasonable expectation of a verdict of not guilty.” More alarmingly, he indicated that neither he nor Pillsbury believed they had the full facts of the case, writing, “nothing has developed which satisfies either of us that she is innocent, neither of us can escape the conclusion that she must have had some knowledge of the occurrence.”12 This admission indicates an intention to prosecute despite the sense that neither of them was confident they possessed the full story of the case. “Some knowledge of the occurrence” is not the same as Lizzie’s having planned and committed the acts entirely by herself, but that was the theory the prosecution presented to the jury.

As an attorney, Knowlton’s skills were not limited to his ability to incisively question. He could also be eloquent in his arguments. In the trial he remarked,

That aged man, that aged woman, had gone by the noonday of their lives. They had borne the burden and heat of the day. They had accumulated a competency which they felt would carry them through the waning years of their lives, and hand in hand they expected to go down to the sunset of their days in quiet and happiness. But for that crime they would be enjoying the air of this day.13

Knowlton could likewise be astute, as when he ridiculed the possibility of a killer coming in from outside the household. During his summation at the trial, he stated, “Never mind the impossibility for the present of imagining a person who was so familiar with the habits of that family, who was so familiar with the interior of that house, who could foresee the things that the family themselves could not see, who was so lost to all human reason, who was so utterly criminal as to act without any motive whatsoever, as to have gone to that house that morning, to have penetrated through the cordon of Bridget and Lizzie, and pursued that poor woman up the stairs to her death, and then waited, weapon in hand, until the house should be filled up with people again that he might complete his work” (1790). The assumption that an outside killer would have no “motive whatsoever” is a rhetorical flourish unwarranted by the facts. A murderer from outside the household might have had a motive that the authorities had failed to ferret out.

Knowlton also made a well-taken point at the trial about how Lizzie might benefit from class prejudices by contrasting her with Bridget Sullivan:

One [woman, Bridget] is poor and friendless, a domestic, a servant, uneducated and without friends, and the other [Lizzie] is buttressed by all that social rank and wealth and friends and counsel can do for her protection . . . supposing those things that have been suggested against Lizzie Borden had been found against Bridget Sullivan, poor, friendless girl. Supposing she had told wrong stories; supposing she had put up an impossible alibi; supposing she had put up a dress that never was worn that morning at all, and when the coils were tightening around her had burned a dress up that it should not be seen, what would you think of Bridget? Is there one law for Bridget and another for Lizzie? God forbid (1856-1857).

Just as Lizzie’s lawyers would attempt to use sexist stereotypes of a pro-female character on Lizzie’s behalf, Knowlton tried to use anti-female sexist prejudices to her detriment. In his summation at trial, he tried to use the idea of feminine wiles to persuade the all-male jury to overlook the fact that all witnesses agreed she was neither blood-stained nor even disheveled when they saw her right after the brutal murders. How had she appeared clean and neat as a pin right after viciously slashing her father ten times? “I cannot answer it,” Knowlton said to the jurors. “You cannot answer it. You are neither murderers nor women. You have neither the craft of the assassin nor the cunning and deftness of the sex” (1838).

Although Lizzie’s inquest testimony was excluded from the trial, many in the public read it while the trial was still in progress as it was published in its entirety in the New Bedford Evening Standard, on Monday, June 12, 1893. In fact, it was Hosea Knowlton who had provided the Standard with a copy of Lizzie’s inquest testimony, subject to release the moment it was admitted or excluded.14

While the Borden trial ended in defeat for Knowlton, he was soon to know a major triumph when he won election as Massachusetts Attorney General, replacing Arthur Pillsbury. He would be re-elected four times to serve five terms. While Attorney General, Knowlton went before the state legislature to urge the abolition of capital punishment, and proved to be one of the foremost advocates for its elimination. His articulate views argued that, “the punishment of murder by death does not tend to diminish or prevent that crime,” and that the death penalty “is a relic of barbarism, which the community must surely outgrow, as it has already outgrown the rack, the whipping post and the stake.”15 He contended with renowned “strenuousness” that the “statute for the death penalty is not in accord with our civilization, nor is it wise in policy.”16 Perhaps Knowlton’s position was partially influenced by a sense that juries, such as the one in the Lizzie Borden case, might be reluctant to convict a defendant knowing a guilty verdict would lead to the person’s death.

At the request of Governor W. Murray Crane, Hosea Knowlton served on a commission that revised the corporation laws in Massachusetts. According to the New Bedford Bar Association Memorial, “His administration of the office of Attorney General marked an entire change in the method of conducting the legal business of the Commonwealth and evinced constructive ability of the highest order.”17

In 1901, one year before his death, Hosea Knowlton formed the law partnership of Knowlton, Hallowell and Hammond, after leaving the office of Attorney General. Gen. Knowlton writes that, in that year, he met an old opponent in the courtroom: Andrew J. Jennings. Knowlton represented a woman suing Jennings’ client for breach of promise of marriage. The jilted woman and the man who changed his mind were, like Jennings, residents of Fall River and that was where the case was tried. At this trial, Knowlton emerged victorious and Jennings’ client was ordered to pay $15,000 to the woman (17-18).

Hosea Knowlton’s wife Sylvia also led an active life. Gen. Knowlton writes,

A woman of fine culture and of a lovable disposition, she was very active and popular in various public interests. She served two terms as a member of the School Committee. Around the turn of the century, as the second president of the New Bedford Woman’s Club, the honor of introducing Winston Churchill fell to her when the future Prime Minister of England lectured about his experiences in the Boer War. Her later life was passed in or near Boston, and in Marion. Mrs. Knowlton died in March, 1937, in her 86th year (18).

In the summer of 1902, Knowlton’s mother died suddenly as the result of an accident. He was emotionally devastated and that grief may have contributed to the decline of his own health. Hosea Knowlton died of apoplexy, an illness that results from congestion or rupture of the brain’s blood vessels, on December 18, 1902, at his summer home in Marion, Massachusetts. His funeral was held on December 22nd, in New Bedford, “where there was an impressive service in the First Universalist Church.” The funeral’s large turnout included Massachusetts Governor W. Murray Crane and many other public officials. The President of Tufts College, Dr. Elmer H. Capen, prayed, “the Commonwealth might ever find as faithful servants as was he.” Banks at the city of New Bedford closed at noon and flags were lowered to half-mast in a display of mourning for Hosea Knowlton (16, 18).

The accounts of Rebello and General Knowlton differ as to what became of Hosea Knowlton’s remains. Gen. Knowlton writes, “By his request the ashes of the deceased attorney were scattered over the waters of the bay at Marion. His name is inscribed on a cenotaph in Rural Cemetery, where repose the ashes of Mrs. Knowlton” (18). Rebello notes that according to Rural Cemetery records, he is buried there.18 On December 29th, 1902, the Boston Daily Globe reported that, “The remains of Ex-Atty Gen Hosea M. Knowlton were cremated at Forest Hills Saturday morning [December 27th]. The body was brought from New Bedford, arriving at the terminal station shortly after 9 o’clock, and was taken to the crematory.”19

Although best known for a famous courtroom defeat, Hosea Knowlton “earned the distinction, while attorney general, of having tried more murder cases than any other man who ever held the office,” and he argued cases before both the supreme judicial court of Massachusetts and the Supreme Court of the United States. He lived a rich, full life, both personally and professionally. In his brief fifty-five years, he accomplished a great deal and enjoyed the respect of his peers, reporters, the electorate, and government officials. In his lengthy obituary, it was said of him that, “every newspaper man of any experience in Boston knew [Atty] Gen Knowlton well, and to most of them his death will be a personal loss. Brusque, surprising at times, he never refused an interview, and was always precise in his statements and kindly when the proprieties bide him say nothing. . . . His good deeds will probably never be recounted.”20

Endnotes:

1 Leonard Rebello, Lizzie Borden Past & Present (Fall River, MA: Al-Zach Press, 1999), p. 194; The Biographical Card File of Massachusetts Legislators, held by the Reference Department of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, emailed to me on April 4, 2005.

2 Rebello, p. 195.

3 The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001-05, http://www.bartleby.com/65/un/UnvrslCh.html.

4 Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography, http://www.uua.org/uuhs/duub/articles/winchester.html.

5 Rebello, pp. 194-5.

6 “Had Peaceful End,” Boston Daily Globe, 19 December 1902.

7 General William Knowlton (ret.), “Hosea Knowlton for the Prosecution,” The Lizzie Borden Quarterly (April 1997): 18.

8 Rebello, pp. 194-5.

9 Knowlton, p. 18.

10 Rebello, p. 195.

11 Inquest Upon the Deaths of Andrew J. Borden and Abby D. Borden, August 9-11, 1892, Volume I. (Fall River, MA: Fall River Historical Society; Orlando: PearTree Press, 2004), pp. 75-76.

12 David Kent, Forty Whacks (Emmaus, PA: Yankee Books, 1992), pp. 78-9.

13 Frank H. Burt, The Trial of Lizzie A. Borden. Upon an indictment charging her with the murders of Abby Durfee Borden and Andrew Jackson Borden. Before the Superior Court for the County of Bristol. Presiding, C.J. Mason, J.J. Blodgett, and J.J. Dewey. Official stenographic report by Frank H. Burt (New Bedford, MA, 1893, 2 volumes; Orlando: PearTree Press, 2001), p. 1759.

14 Rebello, p. 245.

15 Rebello, pp. 194-5, 436.

16 “Had Peaceful Death,” Boston Daily Globe, 19 December 1902.

17 Knowlton, p. 17.

18 Rebello, p. 195.

19 “Cremated at Forest Hills,” Boston Daily Globe, 29 December 1902.

20 “Had Peaceful End.” Boston Daily Globe, 19 December 1902.