by Denise Noe

First published in April/May, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

There appears to have been a special relationship between Lizzie Borden and a poetic work entitled “My Ain Countrie.” The words “At Hame In My Ain Countrie” are inscribed in an oak mantle in Maplecroft.

Vida Turner was asked to sing the hymn “My Ain Countrie” at Maplecroft to commemorate the death of Lizzie Borden. Rebello writes, “[Turner] was told by the undertaker not to tell anyone where she had been.” This last sentence adds an eerie touch. Apparently, even details about services connected with Lizzie’s passing were shrouded in secrecy. Perhaps the undertaker and others wanted the singer to be silent because they wished to avoid raking up public interest. Ironically and inevitably, they added a tidbit to the Borden legend and mystique.

Vida Pearson was born in Topsfield, Massachusetts. She wed Fall River native Alfred Turner in 1907. They were members of the Central Congregational Church—the same church Lizzie had attended prior to the murders but stopped going to after her acquittal, and the one Emma had attended before leaving French Street in 1905.

Vida Pearson Turner was a soloist contralto and was an organist for the Fall River Chapter of the Order of the Eastern Star. The website of the Order of the Eastern Star states that it “is the largest fraternal organization in the world to which both women and men may belong.” The organization is oriented toward those with “spiritual values” and open to people of all religions, but closed to those of no religion. Its official purposes are listed as “Charitable, Educational, Fraternal and Scientific.”

Vida and Alfred Turner had two children and six grandchildren. An article lauding their 60th wedding anniversary was published in the Fall River Herald News in 1967.

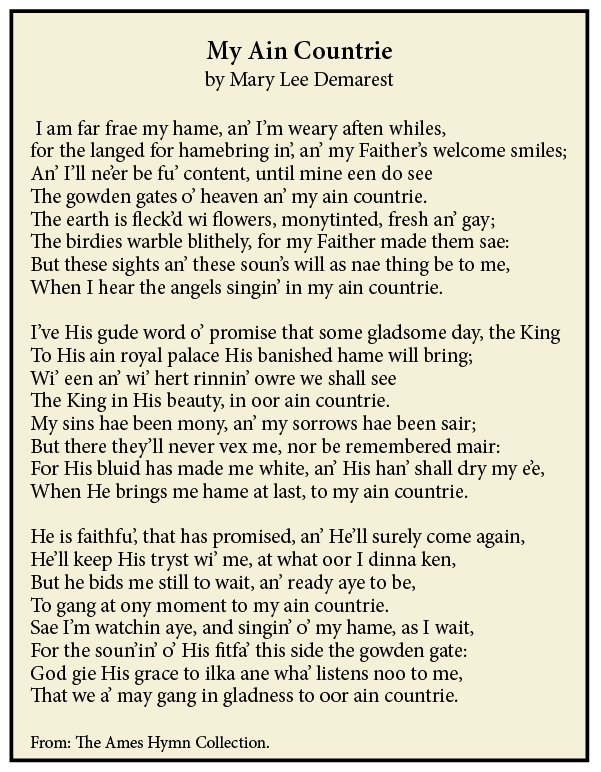

Before “My Ain Countrie” became a hymn, it was published as a poem. Written by Mary Augusta Lee Demarest, the poem made its first appearance in the New York Observer in December 1861. As re-published by Leonard Rebello, “My Ain Countrie” has eight stanzas of four lines each. With one exception, the stanzas follow a pattern in which the first two lines end with the same rhyme and the next two lines end with a different rhyme. In the fifth stanza, rhyming is forsaken in the first two lines.

“My Ain Countrie” is a powerful poem of religious longing. The “countrie” yearned for is that of heaven. The narrator, who could be either male or female, feels “far from my home” and “weary.” They will “never be full content” until entering “the golden gates of heaven and my ain countrie.”

The version given by Rebello is in standardized English. Rebello states in a note that he was aided in translating certain words from Scottish dialect by Mae Conlan Myers and that he and Myers used the glossary of Scottish words by Allan Cunningham, featured in Burns’ Complete Works, to guide them. However, Scottish influence remains evident in the title, which is also a phrase that is repeated at the end of each stanza, as well as in the description in stanza seven of heaven as a “bonnie place.”

Mary Augusta Lee Demarest’s “My Ain Countrie” appears on websites that do not show the poem in wholly standardized English, but rather incorporates Scottish dialect. The Ames Hymn Collection has a version of the poem that has three stanzas of eight lines each. The first line reads: “I am far frae my hame, an’ I’m weary aften whiles.” A website called The Cyber Hymnal displays a rendition of “My Ain Countrie” that also uses Scottish dialect but is divided into stanzas of four lines. However, the poem that appears on The Cyber Hymnal does not seem to be complete. Both of these websites play the hymn and it has a soothing, sweet tone.

Mary Augusta Lee Demarast was an American. Why would she write a poem in Scottish dialect? The reasons are embedded in both her personal background and in the story that served as her inspiration for the poem.

She was born Mary Augusta Lee in Croton Falls, New York, in 1838. Her mother died when she was still young. A Scottish woman often cared for little Mary who picked up her caregiver’s dialect. In addition, one of Mary’s grandfathers was a native of Scotland who often sang Scottish lullabies to lull the child to sleep. Mary Augusta Lee enjoyed the benefit of a good education and showed early literary talent. “My Ain Countrie” was probably her most famous poem.

The genesis of this fascinating poem was a story that Mary had heard and which apparently deeply touched her. That story was about one John Macduff. He and his young wife were said to have left Scotland for America hoping to seek their fortune in a country believed to be one of great economic opportunities. They landed in New York and stayed there a few weeks. Then he, along with the woman with whom he shared his life, soon traveled west to that section of America where they achieved financial success. However, at some point, the wife’s health began to fail. When her husband asked if she was homesick, she is said to have answered, “John, I am wearying for my ain countrie; will you not take me to the sea, that I may see the ships sailing to the homeland once more?”

John Macduff submitted to his wife’s wishes. He sold their home and the couple moved to the eastern seaboard of the United States. She often sat outside and gazed yearningly at ships sailing from the bay. Her health continued to decline and John Macduff believed that his wife was still homesick so the couple returned to Scotland. There she recovered—for she was home.

It is interesting to observe both how Mary Augusta Lee stayed close to the story that inspired her poem and how she departed from it. “My Ain Countrie” shows its origins by being written in the vernacular particular to Scotland. Like John Macduff’s wife, the poem is filled with a sense of longing. However, Mary Augusta Lee made a very significant change because in her poem that longing is not for Scotland or any other earthly abode, but for the home of heaven.

Mary Augusta Lee appears to have had another inspiration for her poem. That other inspiration was a similar poem by Scottish poet Allan Cunningham (who presumably wrote the glossary Rebello found so useful in translating some of Lee’s words). His poem was entitled “Hame, Hame, Hame” (“Home” in standardized English). The final words of the final lines of each verse in “Hame, Hame, Hame” are “ain countree.” Cunnignham’s poem does not convey the sacred feelings of Lee’s “My Ain Countrie” nor does the “ain countree” appear to be heaven. His poem speaks of “usurping tyranny” and has a this-worldly, and even slightly militaristic, flavor to it.

Allan Cunningham was born in 1784, fifty-four years before Lee. Cunningham’s birthplace was Blackwood, Dumfriesshire, Scotland. As a young lad, Allan’s interest in literary endeavors may have been heightened because the famous Robert Burns was a neighbor. When Allan was eleven, he was apprenticed to a stonemason. However, the lad’s interests went in increasingly literary and musical directions. Cunningham eventually published in many venues. He published The Songs of Scotland, Ancient and Modern in 1825, a four-volume set that included some songs he had written himself. It was a varied collection that included ballads, long songs, and religious tunes. The talented and accomplished Allan Cunningham died in 1842.

At the time Mary Augusta Lee published “My Ain Countrie” in 1861, she was still single, age 23. Like Lizzie, Mary Augusta Lee lost her mother at a young age. Indeed, the poet’s personal life has more than one parallel to the lives of the Borden ladies. She approached middle age without a husband, and so was a “spinster” or “old maid” by the standards of the time. However, unlike Emma and Lizzie, but like Abby, she eventually did marry. In 1870, when Mary Augusta Lee was 32, she wed Theodore F. C. Demarest. The couple lived in Passaic, New Jersey. She published a collection of her poems in 1882. In addition to her talent for poetry, she was known for her philanthropic works.

As well as having parallels to the lives of the most famous Borden women, the life of Mary Augusta Lee Demarest has a significant parallel to that of John Macduff’s wife. When Mary Augusta Lee Demarest’s health began to fail, she and her husband left New Jersey for Pasadena, California in the hope that the change might restore her health. There she died in 1888 at the relatively young age of 50. Before marrying, in 1864, Mary Augusta Lee had seen her poem set to a Scottish melody by Hubert Platt Main and Ione T. Hanna to create a hymn.

Hubert Main was born in 1839 in Ridgefield, Connecticut. He grew up in a household in which he been exposed to a great deal of music in his daily life from an early age. His father, Sylvester Main, was a singing teacher. Young Hubert attended singing school until 1854, when he traveled to New York City where he worked as an errand boy in a wallpaper business. This teenaged boy may have wanted to be around a music-oriented business, as in April 1855, he went to work performing errands for the Bristow & Morse piano company. In that same year, he aided his father in editing a songbook that was authored by Isaac Woodbury. In 1867, Sylvester Main joined with Lucius Biglow to take over William Bradbury’s publishing business. The new partnership became Biglow & Main, specializing in hymns, and Hubert Main went to work there.

“My Ain Countrie” became a song through Hanna and Main’s collaboration. The Cyber Hymnal states that this prolific artist also wrote over 1,000 pieces of music. The website also indicates that most of the music he created was religious in character. He was not only a music writer but a music book collector as well and was apparently outstandingly prolific at both endeavors. In 1891, he sold a collection containing over 3,500 books to the Newberry Library in Chicago, Illinois. The collection became known by the aptly wry title, the “Main Library.” Hubert Main died in Newark, New Jersey, in 1925.

Ione T. Hanna was married to a banker and lived in Denver, Colorado. A website about the history of women’s suffrage indicates that she made a successful venture into politics. An article on the website states that suffragists in Colorado during the 1890s encouraged women to exercise the limited voting rights they had been granted at that time to demonstrate that females were genuinely interested in voting and could be expected to make use of a broadened franchise. The piece claims that the “most famous deployment of this strategy” was “the election of clubwoman Ione T. Hanna to Denver School Board #1 in May 1893, largely through women’s votes.”

Ione T. Hanna possessed musical talent, collaborated with Hubert Main to make a well-known poem into a song, was a wife, was active in clubs, and ran for and held a public office. It appears that Ione T. Hanna was a multi-talented person of varied interests who enjoyed a rich, full life.

Having “At Hame In My Ain Countrie” inscribed into a mantle at Maplecroft and requesting that “My Ain Countrie” be sung at services upon her death indicates that Lizzie Borden felt a strong connection to this poem and hymn. There is no information indicating that the Bordens had Scottish ancestry. Theirs was a French heritage that can be traced to Normandy. Their ancestors traveled to England with William the Conqueror. They lived in the county of Kent. At some point, the Bordens went to Wales. In 1635, they immigrated to the English colonies in America.

People often have interests in and attractions to countries and cultures without having ancestry from that area. Emma Borden visited Scotland in 1906. Both sisters appear to have been fond of Scottish poetry and music.

Lizzie must have had a special feeling for the very phrase “At Hame In My Ain Countrie” as well as the hymn “My Ain Countrie.” What was it about that phrase that resonated with her? Perhaps because it partly explained what some people have seen as her puzzling decision to remain in Fall River after the trial when she found herself ostracized there. The feeling of being at home may have been so primary to her that she felt herself too much a part of Fall River to leave it.

It is also likely that “My Ain Countrie” spoke powerfully to Lizzie as a hymn. Like most Christians, and many adherents of non-Christian religions, she probably cherished hopes for an afterlife. “My Ain Countrie” sings of a celestial home. Lizzie, who had endured loneliness and the scorn of her neighbors for so many years, may have richly appreciated the prospect of a heavenly home to which she hoped she would be warmly welcomed.

Works Cited:

“About the Order of the Eastern Star.” General Grand Chapter Order of the Eastern Star. 10 May 2008 < http://www.easternstar.org/aboutoes.htm>.

Demarest, Mary Lee. “My Ain Countrie.” The Ames Hymn Collection. 10 May 2008 <http://junior.apk.net/~bmames/ht0137_.htm>.

Demarest, Mary Lee. “My Ain Countrie.” The Cyber Hymnal. 10 May 2008 < http://www.cyberhymnal.org/htm/m/a/mainctry.htm>.

Rebello, Leonard. Lizzie Borden: Past & Present. Fall River: Al-Zach Press, 1999.

“Why Did Colorado Suffragists Fail to Win the Right to Vote in 1877, but Succeed in 1893?” Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000. 10 May 2008 < http://womhist.alexanderstreet.com/colosuff/intro.htm>.