by Denise Noe

First published in August/September, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

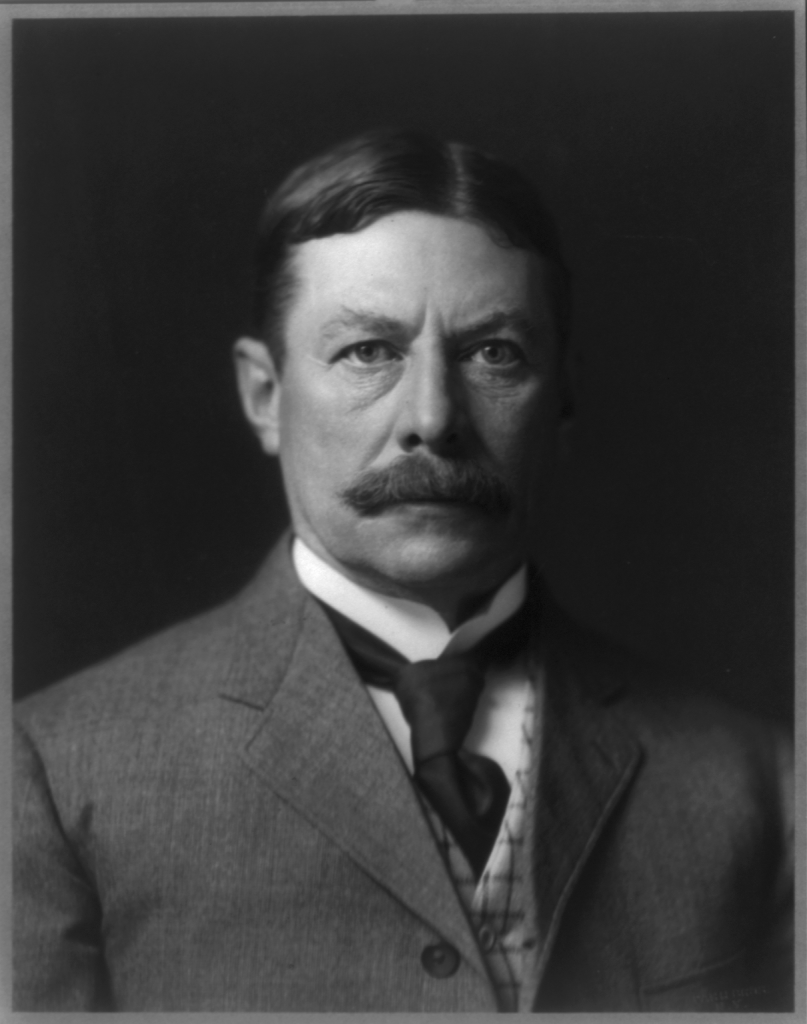

Borden buffs know William Henry Moody as one of the prosecutors of Lizzie Borden. Less well known are the facts that after the trial he went on to become a four-time congressional representative, a Secretary of the Navy, a U.S. Attorney General, and a Supreme Court Justice.

Indeed, it is hard to imagine a more extraordinary and accomplished career than that of William H. Moody. The man who would pursue that multi-faceted career, and earn himself a permanent place in Borden lore along the way, was born in 1853 on a farm in Newbury, Massachusetts. When growing up, he attended public schools in Salem and Danvers, Massachusetts. He graduated from Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts in 1872.

As a young man, he attended Harvard University where he proved himself a bright person and conscientious student by graduating third in his class in 1876.

Two Years Before the Mast

Moody studied law with Richard H. Dana, Jr. (1815-1882), author of Two Years Before the Mast. Since the world of the sea and ships would come to play a surprisingly significant part in Moody’s life, it is worthwhile to examine the life and work of Moody’s legal mentor. As Moody would after him, Dana attended Harvard. However, before he could graduate, he was stricken with the measles. This illness negatively affected his eyesight. Doctors suggested that a sea voyage might improve his vision.

How could a voyage improve vision? A writer on a medical newsgroup who calls himself “Zetsu” answered the question as follows: “A sea voyage would improve his vision because of the continuous wobbling and shaking about on the ship/boat. This movement causes the illusion in one’s field that the surrounding objects are moving in an oppositional direction. This illusion is restful to the mind and therefore improves the sight by relieving strain which causes imperfect sight.” The same writer elaborated, “I also presume that the recommendation was given because a sea voyage would improve his general health by being in the open fresh air, and by eating fresh seafoods.”

However, the Communications Administrative Manager for the American Academy of Opthalmology, Georgia Alward, wrote, “I do not know why a doctor would suggest a sea voyage to improve vision that was affected by the measles” and “I could not find any documentation where a sea voyage would help” with vision. She believed that such advice might be the product of “an old wives tale.”

At any rate, based on the advice Dana received, he became a sailor aboard a boat called the Pilgrim. The ship sailed to California, at the time a part of Mexico. He kept diaries during the voyage and, when it was over, worked from those entries to create Two Years Before the Mast. A website about Dana calls it “one of the best accounts of life at sea.” The book also had positive practical effects as it led to reforms in the working conditions of sailors. Dedicated to that cause, Dana traveled throughout the United States and to Great Britain to give speeches about the importance of improving the lot of sailors.

Apparently, the voyage also had its intended effect as Dana’s vision had improved by the time he returned to the landlubber’s lifestyle.

Dana had a good bit of the crusader in him as he took on another controversial cause: that of the enslaved. As an attorney in Boston, he represented several escaped slaves against the federal government that sought to return them to their Southern owners. Dana took no fees for this work. He also suffered for his principles as one pro-slavery advocate assaulted Dana because of it.

Perhaps Moody was influenced by his mentor’s steadfast commitment to principle as well as Dana’s special interest in the lives and working conditions of sailors.

Entering the Borden case

Moody was admitted to the bar in Salem, Massachusetts in 1878. He began his practice in the Massachusetts city of Haverhill. There the young and ambitious man was soon active in local politics as a Republican. He served on the local school board, was city solicitor, and was elected Essex County district attorney. His intelligence and legal skill caught the attention of Massachusetts Attorney General Albert E. Pillsbury, who appointed Moody to assist Hosea M. Knowlton in prosecuting Lizzie Borden.

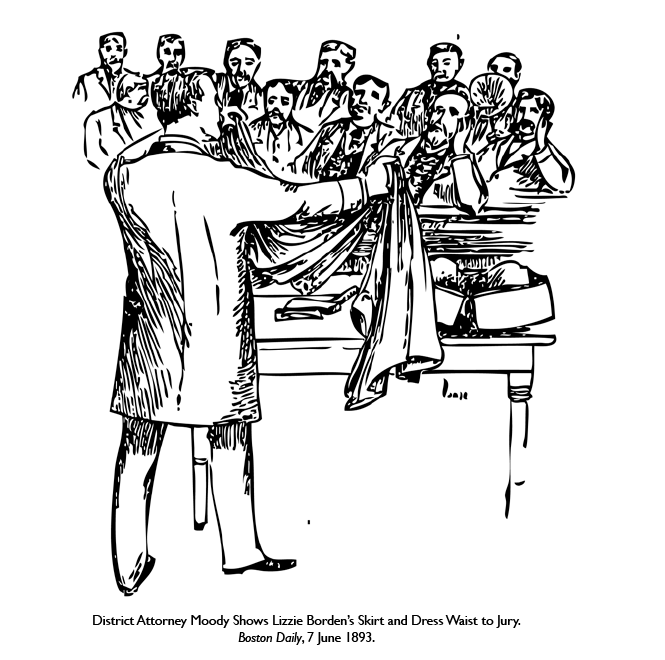

It was Moody’s first murder case. The junior prosecutor started by making what was arguably a major strategic blunder for his side. Leonard Rebello in Lizzie Borden Past & Present writes, “It was Moody who suggested George Dexter Robinson be retained by the defense.” The very able Robinson, who had once been Governor of Massachusetts, may have been largely responsible for winning Lizzie Borden her acquittal.

The young Moody gave the opening argument for the prosecution. He began with a description of the crime that was powerful in its simplicity: “Upon the fourth day of August of the last year, an old man and woman, husband and wife, each without a known enemy in the world, in their own home, upon a frequented street in the most populous city in this County, under the light of day and in the midst of its activities, were, first one, then, after an interval of an hour, another, severally killed by unlawful human agency.”

Moody immediately continued to the fact that an extraordinarily unlikely person became the suspect and then defendant, saying, “Today a woman of good social position, of hitherto unquestioned character, a member of a Christian church and active in its good works, the own daughter of one of the victims, is at the bar of this Court, accused by the Grand Jury of this County of these crimes.”

He suggested the root of the motive for the murders, saying, “There was or came to be between the prisoner and her step-mother an unkindly feeling” and briefly reviewed the tension between Lizzie and Abby over Andrew’s gift of a share in a building to Abby’s half-sister.

The junior prosecutor gave an extremely detailed description of the Borden home, noting that his depiction was “wearisome” but indicating that it was necessary to understanding the prosecution’s case. He detailed the movements of all those known to be in the Borden home at or close to the time of the murders, including Uncle John Morse, Bridget Sullivan, the victims, and the accused.

Toward the conclusion of the opening statement, Moody suggested that the jury would not be able to find “any other reasonable hypothesis except that of the guilt of this prisoner” to “account for the sad occurrences which happened upon the morning of August fourth.”

Taken as whole, Moody’s opening argument must be considered more than competent and genuinely eloquent in both its beginning and its ending.

Congressional representative and bachelor

Although Moody’s side was defeated in the Borden case, prominent Republicans respected the skill he had displayed in it and his career continued on a steady rise.

The ambitious Moody spotted an opportunity when United States Representative William Cogswell died, leaving a vacant seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. Moody was chosen to fill that seat in 1895.

When he gained this office, Moody was 42 years old. The vast majority of people are married by that age. However, like Abby Durfee Gray and Emma and Lizzie Borden, William H. Moody entered middle age without a spouse. Unlike Abby, but like Emma and Lizzie, he would remain single until his death.

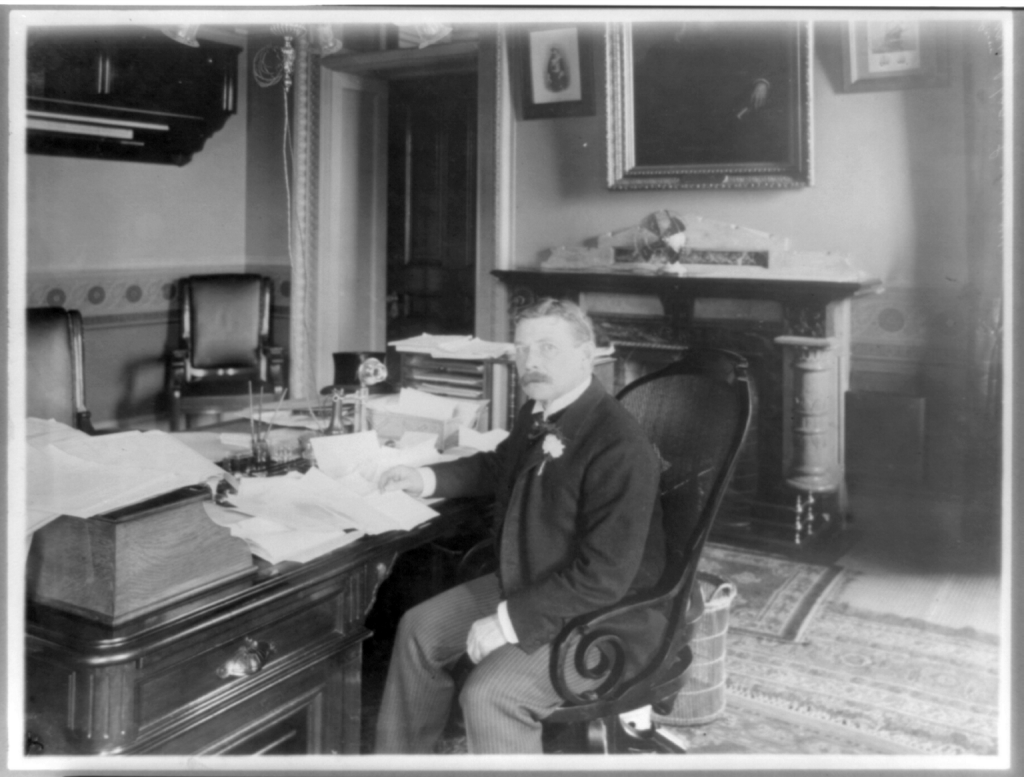

It can be surmised that the constituency of the district he represented in the House appreciated his service since they elected him three times. A New York Times article reported he was “well and favorably known as an industrious and active member of Congress” and that he served on the Appropriations and Insular Affairs Committees. The Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships describes Moody as “making a reputation by his knowledge of parliamentary procedure and his perseverance in debate.”

Theodore Roosevelt’s friend and associate

The politically astute Moody cultivated friends in important positions. One who would prove most significant was Theodore Roosevelt, a New York police commissioner at the time the pair became close.

It is likely that the two men were drawn together in part because of a shared interest in seafaring matters. Moody had studied under Dana, the author of Two Years Before the Mast. Theodore Roosevelt was the author of The Naval War of 1812. It was T.R.’s first book, partially written while the young Theodore Roosevelt was still in college. The Naval War of 1812 would become a standard for naval strategy studies and was required reading at the Naval Academy in Annapolis for many years. In 1897, President William McKinley appointed T.R. Assistant Secretary of the Navy. He served little more than a year in that capacity before resigning to become Lieutenant Colonel of a regiment that would become famous as the “Rough Riders.”

Perhaps a shared love of athletics also helped bond William H. Moody and Theodore Roosevelt in friendship. Moody was a physically active and athletic sort who enjoyed walking, bicycling, riding horses, and playing golf. At one point, Moody served as President of the New England Baseball League. Pictures of Moody show a robust man with a ruggedly handsome face and slightly waved hair. The New York Times reported that some people actually mistook Moody for T.R. because of both their physical similarity and “a similarity in the decisive manner of both men.”

This friendship with T.R. would be crucial to Moody’s elevation to high office. In 1901, Vice-President Theodore Roosevelt became President Theodore Roosevelt after the assassination of President William McKinley.

In 1902, Secretary of the Navy John D. Long resigned his office. According to a New York Times article, about six people aspired to the position. After a brief time, the contest narrowed to two Congressional Representatives. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, a man much respected by the Theodore Roosevelt administration, sponsored Representative William H. Moody and the President appointed Moody Secretary of the United States Navy. At 49, Moody became the youngest member of the President’s Cabinet.

In January 1903, Secretary Moody was injured in an accident on the Naval Academy grounds at Annapolis. Accompanied by Senator Eugene Hale, who chaired the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, Moody was at Annapolis to inspect new buildings. Moody was in a carriage when a 17-gun salute was fired to honor him and the Senator. The horses pulling the carriage were startled by the noise and they suddenly swerved and dashed as the driver frantically but futilely attempted to control them. The carriage’s pole broke, further distressing the horses that ran even faster. As the horses madly pulled on the carriage, Secretary Moody opened a carriage door and leaped to the pavement. He landed on his face and was struck unconscious. The Secretary was lifted up and carried to a nearby home where he soon awakened. Luckily, he sustained only cuts and bruises from this mishap.

Moody served as Secretary of the Navy for two years.

Attorney General, Supreme Court Judge, and namesake

In 1904, the President appointed Moody United States Attorney General. Attorney General Moody helped craft the anti-trust campaign waged by the Theodore Roosevelt administration that helped dissolve the Standard Oil Corporation.

In 1906, Moody was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Thus, Moody had the distinction of serving in all three branches of the American government: Legislative, Executive, and Judicial.

As a Supreme Court Justice, Moody authored several important opinions. He pioneered the doctrine that corporations could be legally restricted in what they charge, in an opinion he wrote on the cases brought concerning the Knoxville Water Company and the Consolidated Gas Company.

He served on the Supreme Court for four years before retiring in 1910 because of his failing health. He suffered from a severe and disabling form of rheumatism. After resigning from the Supreme Court, he returned to Haverhill where he lived with a sister who, like him, had never married. No longer physically able to enjoy the sports he had loved throughout most of his life, the ailing Moody spent almost all of his time in the home.

William H. Moody died on July 2, 1917, at the age of 63. He is buried in the Byfield Cemetery that is located in Georgetown, Massachusetts.

Two years after his demise, on June 28, 1919, a Naval Fighting Ship commissioned Moody was launched. William H. Moody’s sister, Mary E. Moody, sponsored the ship.

The Moody would serve its country for eleven years. Among many other services, it brought torpedoes and ammunition from Rhode Island to California where it operated along the California coast. The ship was used on an inspection tour of Alaskan coal and oil fields. It was used in fleet exercises and good will visits. In 1927, the Moody was used in tactical maneuvers with the U.S. Fleet in the Caribbean. At one point, the Moody operated out of the Guantanamo port and out of Gonaives in the defense of the Panama Canal. Since negotiating the treaty that would lead to the construction of the Panama Canal was one of the major accomplishments of the Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, who had done so much to further of the career of William H. Moody, it was especially appropriate that the ship named after Moody was used to defend the Panama Canal.

In 1930, as a part of a disarmament agreement, the Moody was decommissioned. Much of the ship was sold as scrap metal. Her hulk was sunk in 1933. Like her namesake, the Moody is no more but like him she had had a very productive run—or sail.

Works Cited:

“Ex-Justice Moody Dies At His Home.” New York Times, July 2, 1917.

“Justice Moody Resigns.” New York Times, October 5, 1910.

“Moody.” Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. 27 July 2008 <http://www.history.navy.mil/danfs/m14/moody.htm>.

“Moody, William Henry,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. 27 July 2008 <http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=M000883>.

Rebello, Leonard. Lizzie Borden Past and Present. Fall River, MA: Al-Zach Press, 1999.

“Richard Henry Dana, Jr.: (1815-1882) Two Years Before The Mast.” Winthrop Denmark. 27 July 2008 <http://www.winthrop.dk/rhdana.html>.

“Secretary Long Resigns.” New York Times, March 11, 1902.

“Secretary Moody Hurt.” New York Times, January 13, 1903.

“William H. Moody.” Oyez: U.S. Supreme Court Court Case Summaries, Oral Arguments & Multimedia. 27 July 2008 <http://www.oyez.org/justices/william_h_moody>.