First published in October/November, 2004, Volume 1, Issue 5, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

The Ellsworth American,

Thursday, January 3, 1985

Reprinted by permission of the Ellsworth American.

A Solution to the 1892 Crime?

Ruby Cameron Says David Anthony Murdered Lizzie Borden’s Parents

By John R. Wiggins

Lizzie Borden was, and still is, widely suspected of having taken an axe to hack her father and her step-mother to death in Fall River, Mass., shortly before the turn of the century.

“Lizzie Borden took an axe

And gave her father forty whacks;

And when she saw what she had done,

She gave her mother forty-one.”

So went the popular jingle that condemned Elizabeth Borden for a crime that was never proven. Elizabeth lived on, alone in the family house where the double murder took place, until 1927. When she died, the secret of who really killed the elder Bordens apparently died with her.

Ruby Cameron of Cherryfield, however, may have the last word on the matter. Miss Cameron, professionally known during her long career in nursing and health as Dr. Cameron, is, at ate 84, the last living link with people who may have been deeply involved in the event.

Miss Cameron says that David Anthony, who wanted to marry Lizzie, committed the murders in a fit of rage during one of frequent Borden family feuds. David later lived with the Cameron family. Ruby, who as a very young child grew to become fond of him, did not suspect until years later what role David and her own parents played in the unsolved Burden murder case.

“I was born in New Bedford on April 19, 1900, and worked at Massachusetts General Hospital and then got a bachelor of science degree as a registered nurse from Columbia University in three months. Later I got a master’s degree in English literature from Florida. In 1945 I got my doctorate from Chapel Hill in biochemistry. During my career, I put 45 consecutive years

into nursing work, plus doing many other things,” says Miss Cameron with some pride.

Today she limps from a recently broken leg and she is a bit hard of hearing, although that handicap is eased by a new hearing aid given her by a friend. Of the leg, she says, “I never let it get the best of me, but I worry about falling down the stairs, and sometimes I do say ‘damn.’”

She claims that her new hearing aid is very comfortable. “It only bothers me when I am typing. I am just finishing my memoirs, which are about 125,000 words long. I have six final pages to write. It is about my career and the work I have done and the people I have known.”

The memoir includes Lizzie Borden. Miss Cameron has never spoken of that case until last week, when she decided that the time has come to tell what she always regarded as her own family secret.

“David Anthony was the son of a very wealthy family that my father worked for. The Bordens said David was crazy. He wasn’t, really. He was just a brilliant mechanic. The only thing he was crazy about was motorcycles. In 1892, you did not have cars or telephones or electricity. When David went helling around on his motorcycle scaring horses, people didn’t think much of him for it.

“Mr. Borden and his second wife called him crazy and refused to let Lizzie marry him. There were many feuds in the Borden family.

“Nora Donahue worked in the Borden home as Lizzie’s maid. She came from Ireland and had only been in the United States for six months.

“My own mother, Margaret Johnson, was a maid in the Anthony home. She was from Reykjavik, Iceland. She was engaged to marry my father, John Cameron, who worked for the Anthony family first in Fall River and then went into business with them, opening the first meat packing plant in New England. It opened in 1890 in New Bedford. My father was a first-class engineer. He went with the Anthonys as his first job after getting out of the British Navy. He married Margaret on Dec. 22 in 1892.

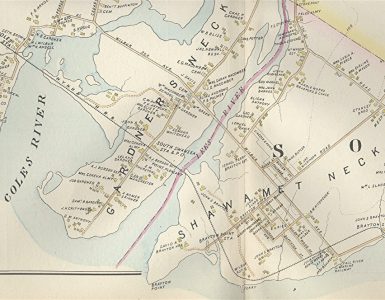

“There is one thing I don’t remember. I would like to have a map of Fall River as it was in 1892, because I don’t know how Nora ever got David over to my mother, who went and got my father, who took them all away. They disappeared: David, Nora, and Maggie. My father probably saw what happened and wanted to protect the Anthonys.

“It so happened that father was going to take over the Anthony meatpacking plant in New Bedford at about that time. He never did. He and mother bought the old Kempton farm on the outskirts of New Bedford, instead. That’s where they went after it happened.

“How father ever got them out of Fall River, I don’t know. The city only has one inlet and one outlet, the narrows over the river. Communications were so slow in those days. He could have been in New Bedford before anyone looked at him. I have sent to the Fall River Historical Society and to the New Bedford Standard and to the New Bedford Public Library asking for a map of that time. I haven’t had a reply yet.

“Lizzie couldn’t have swung an axe to split their skulls. She wasn’t strong enough. At any event, they couldn’t find an axe, not until years later, after Lizzie died.

“A couple of years before the New Bedford fire of 1930, Dr. Trudeau of Massachusetts General Hospital, who had his own hospital in Fall River, wanted me to take care of Lizzie in her last sickness. My mother refused to let me do it. She said, ‘I’ll see you dead before you go there!’ Mother always called Lizzie Borden ‘that woman.’

“So instead of taking the case, I got a classmate of mine and we went over there to the Borden home. That was when I talked with Miss Borden, herself. She kept saying, ‘You are Maggie’s daughter!’ I said, ‘Yes. I’m Ruby Cameron.’

“I got the other nurse to take the job, so I didn’t stay with her, but I met her and talked with her and saw how unfairly she had been maligned. There is no question but that she had a lonely life.

“I decided to shut my mouth forever, because it was clear to me that my own mother and father knew that David had killed the Bordens, and Lizzie, of course, knew it, too. You see, they would all be accessories to the fact. Now, 55 years later, I am the only one left, and it doesn’t matter.

“Lizzie and my mother let me see the truth. Father was dead. When mother forbade me to nurse Lizzie before she died, out of respect for Dr. Truesdale I did visit Elizabeth Borden, but I got another nurse to do the job.

“Mother kept talking about how she had got Jack, my father, to get them out of Fall River. ‘We all had to go,’ my mother said. ‘When Papa saw us, we got into the wagon, ad we sat in the back of the wagon, huddled out of sight, until we got to New Bedford!’

“Mother said, ‘I screamed for Jack when Nora brought David over.’

“The Anthony home must have been near the shop where Father was working. Mother screamed, and Father came into the house and then hurried them into the wagon and headed for New Bedford.

“Mother was 17 then. Nora was only 16 or 17. They were two kids. They wouldn’t even have known where they headed for. David was about 20 when it happened. David was a fine, fine fellow. He really was. He came to work at the factory with Father in New Bedford after the fracas, after the trials were over. He worked there with my father.

“David had a dozen motorcycles. He was crazy over them. He would go off to visit someone once a week. One day he made a little seat and attached it to the front of the motorcycle and sat me on it and said, ‘I’m taking Ruby for a ride.’ My parents must have consented. We went to Fall River to see a woman. Once a week we would ride to see that woman. She gave me a jellyroll cake and a glass of milk while they talked to each other. I didn’t know who she was. That was in 1910. I went on longer than a year. Everybody else was scared to go with him, but I had a good time. I still have a motorcycle of my own. He was a fine, fine person.

Lizzie’s own mother had been a very wealthy woman. She left money both to Lizzie and to her sister. Lizzie’s father and her stepmother were taking Lizzie’s money and not giving her any. They didn’t want her to marry David because they wanted that money. Nora kept saying to Mother, ‘I wonder how rich they really are?’ There was a lot of money involved. Her real mother had left her a big estate, including a couple of textile mills.

“Mother died in 1932. She and Nora stayed together all their lives. Me, the dummy, didn’t know why, not until I had met Lizzie. The real picture came to me then. Mother and Father were implicated and were just as guilty as David. I decided to keep my mouth shut when I realized what had happened.

“David had killed them in a fit of fury. David got tearing mad because Lizzie’s father wouldn’t let him marry her and had laid down the law. They fought then and there. David went out and picked up an axe in the back of the shed and came in and destroyed both of them before anybody could say boo! It was done in a fit of anger.

“Lizzie had nothing to do with it. She was a victim. She wouldn’t say anything because she loved David. He loved her, too. I don’t understand why he didn’t marry her when it was all over. I know that he went over and saw her every week. I was with him. Whether her lawyers or her doctor had decided to that it would be best if she didn’t marry him, I don’t know. I don’t even know how much her lawyer knew or how much the Anthonys knew. Mr. Anthony was an important businessman, and I have my doubts as to how much would have appeared in the papers. I wonder if the old files at the Providence Journal were washed away in the hurricane of 1928. The Anthony family published the New Bedford Standard and they might not have wanted to publish much about this case. David’s uncle controlled that paper as well as many businesses in New Bedford.

“David died of influenza in 1917. He was buried in the same lot with my infant brothers in an unmarked grave. In those days, they bought big family lots in cemeteries. My two brothers died in 1895

and 1897. They died in infancy, at two weeks. They were buried in a single grave. I wasn’t born until 1900.

“In 1917 the influenza was awful. They didn’t wait when you died. They put you right into a grave. I worked at the Grace Episcopal Church taking care of people during the epidemic, and worked at the mill, in addition. David was terribly sick, and then it was over, and he was gone.

“Nothing was ever said about it at home. If I ever mentioned Lizzie’s name, father would raise his hand for silence. How much he knew, I never found out. He forbade me to even mention Lizzie’s name. He was dead when I finally went to see her.

“My friend who took the job as Lizzie’s nurse was Doris Humphrey. Doris did not know the true story. When Dr. Truesdale asked me to take that job, he said, ‘Your mother was a friend of hers. I think it would be better if you took care of her.’ When I told him I couldn’t take the job, he said, ‘Well, find someone you can rely on, then.’

Miss Borden left her nurse $10,000. Doris raised a family and bought a home with the money. It was the one happy swing of that whole mess.

“I don’t know where all of Lizzie’s money went after she died. She probably left it to the Audubon Society or the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. I would have to find out by looking at the will. She was in her late seventies when she died. That must have been around 1928. There wasn’t any work around for nurses then. People couldn’t afford nurses. But I never stopped working. I always had jobs.

“Elizabeth Borden was a fine old lady. There was nothing wrong with her. She lived a solitary life. She had a housekeeper, but when she was sick there was nobody who stayed with her but the nurse. Doris had all the meals brought in or cooked them herself right there in the house during Lizzie’s last six weeks.

“People used to ask, ‘Where is the axe?’ They found the axe after they tore the Borden barn down, six months after Lizzie died. They found an axe in the double wall. They couldn’t prove it was the right axe, though. It was all rusted. They never proved anything. They didn’t do real sleuthing then. It was a different era. If somebody was killed, that was that.

“From what I saw of David as a child, I liked him very much. I used to play at the meat factory that father managed. Father had an engine built for the pullies that ran the meat grinder. My father made a steam engine, and in 1932 I was given $50,000 for that engine. It ran on kerosene. It still worked in 1932. That was in the Depression, when there wasn’t a cent around, that I sold it. It ran the meat grinder.

“In 1905, Jonathan Swift was out to beat the meat market, and he did. Harold Anthony decided to sell to Swift rather than to fight him. Then John Armour came to New Bedford to see my father, because it was my father’s recipes that the plant was using. He bought my father’s sausage, ham, bologna, and pressed ham recipes. That was back in 1905. That was when David and my father moved the machinery to our home outside New Bedford. We had a meat factory in our cellar. David stayed there, in our house. Father built up a small factory at home. There was a big smokehouse, then, that was always filled with frankfurters and hams and bacon. Nobody stole anything in those days. We left the smokehouse full.

“Father built a cooler in the cellar. Then Mr. Grump, who had come from Germany, come to work for my father. War broke out, and public hatred of all Germans began. Father took the cooler and converted it into a home for Mr. Grump, who lived there all four years of the war. People were out to get him. They thought he was a spy or something. He wasn’t. You wouldn’t know how people treated Germans in this county during that war. My father stayed right with him all through the war and protected him. The last time I saw that house was in 1957. I was sick when I saw the trees all gone and the junkyards all over. Well, you can’t always have it your own way.

“I was too young to truly appreciate David as a person. I just knew he was a nice fellow who worked for my father. Looking back, I am not sure it was Lizzie that we visited on those motorcycle trips, but

who else would we have gone to see? Who else would treat me so kindly and set me at the table so they could go to the front room and chat. I recognized the house in 1927, when Dr. Truesdale sent me to see her before she died. That was when the whole picture came to me. I said to myself, ‘Now I see!’ I could see Nora pulling David from the room where it happened and getting the bloody clothes out of the way and going to get Maggie, so Jack could get them out of there. Father, with his foresight, got them all out of there.

“It must have been three or four hours before anybody else went in there and discovered Lizzie’s predicament. I don’t know. I am not going to make up anything I don’t know.

“Lizzie was bedridden when I last saw her. She was very much on her last legs, ready for the final count. She could do some things for herself, but she needed someone to feed her and take care of her. Her doctor was very loyal to her and wanted her to have the best of care. His name was never mentioned in all the publicity. I would like to see a copy of her will. If I see what is in it and how much money was left to whom, I would learn something, perhaps. Her sister was still living then. There was no love lost there. I am quite sure David did it. I asked Doris to find out, when I gave the job to her, but then Doris got too curious, and I said, ‘No more.’

“David was a fine person, as I look back on it now. Who else would have thought to take a child along for a ride on his motorcycle? I don’t know what they talked about in the next room. I was having a good time and had something to eat. What did I care about them? I don’t think David even had an obituary in the papers when he died. During the influenza epidemic nothing was put in the papers about people who had died. They were dying all the time. The influenza was terrible.

“Lizzie, when I last saw her, was mentally sound. She never was unsound. She died of pneumonia, of course. That was the last complication that took her. She was a beautiful woman. She wore her gray hair back straight and was always very neat. She had beautiful night clothes. She loved fancy night clothes. Everything I saw about her, I liked. Maggie and Nora had only seen her a short time. How could they know her? Maggie and Nora were two scared little kids. Nora was fresh from Ireland and glad to have a job in the Borden home. Nora and my mother never separated. They never parted company. They lived within three streets of each other the rest of their lives.

“Lizzie was a gentle person, a gentle cultured woman brought up with undoubtedly excellent tutors. They were rich enough to hire teachers and tutors. In those days, there was a lot of music in Fall River, and I imagine it played a part in her life, but I don’t know.

“My father was working for the Anthonys when it happened, and he was protecting the Anthony boy, as he did all of his life, until he died. They worked together beautifully. They had the same temperament. They were both engineers.

“Lizzie spent the rest of her life alone in that house. She was wise enough to know that if she had gone out in public, eventually somehow things would have leaked out and gossip would have torn her apart. It’s gossip that does that to people.”

In her retirement, Miss Cameron has written two novels and is working on her memoirs. “I have six more pages to go on the memoir. The first novel is a story about an academy in New Hampshire. The second novel is about a candystriper, a nurse who takes one suffering dropout, and then seven other girls, and makes decent women out of them. It is a Christian story.

“I started the memoirs five years ago. There are ten chapters and 125,000 words. I rewrote it as I worked on it.

“I thank God for my parents’ brilliance. When my mother came from Iceland at age 17, she had a college degree and spoke five languages. She was a Scandinavian and had blond hair. Father once said, after mother had been very sick, that her hair used to be yellow gold and hung down to her knees. ‘You don’t know how many times I combed your mother’s hair!’ he said to me. He worshipped my mother.

“I have the best parts of them both, I think. I have the brains, and I have the same attitude, in many ways.”

Miss Cameron indulges and interest in politics. “I am a registered Republican, but I vote independently. When I last talked with Sen. George Mitchell, I asked him something about taxation, and he said, ‘The subject makes me sick.’ He’s a great guy. I lived in Sacramento for several years, running a big farm and cutting a lot of wood off it. Ed Greely in Searsmont once said to me, ‘I want you to meet Ed Muskie.’ That was way back at the time of the liquor scandal. Ed Greely said to me, ‘I am for him. He could turn us around. Will you donate a little money to his campaign?’

“I said I would donate as much as I could. I went back to Boston and took a job and was able to donate $50 a month. I was making very good money working in Boston. I did that for two or three years until Ed Muskie got on his feet and was elected governor, and then senator. When Ed Muskie was getting through, he wrote to me saying, ‘I hope you will stand by George Mitchell as you stood by me.’ I wrote Ed to say that I didn’t have the money I used to have while I was working, but I would contribute what I could.

“The biggest mistake I ever made was after I finished putting the Hebrew Home in Boston on its feet. While I was doing that I met some of the finest Jewish people in the world. That was when Dr. Cook wanted me to meet Golda Meir. They wanted me to go to Jerusalem and open a clinic. I was 68, and I said I would not do it. You don’t have the steam at 68 that you have when you are younger. I did go to South Carolina with Golda, and the people I met with her there said they would give me all the money I needed to go establish a clinic. I turned it down, but I have the friendship of those Jewish people to this day.”

Miss Cameron has the friendship of many people she has known and worked with in the past 84 years. “I got over 150 cards this Christmas. I have answered all but four of them with letters. I am glad that so many people remember me and still want to keep in touch.”