by Sherry Chapman

First published in August/September, 2005, Volume 2, Issue 4, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Lizzie Borden’s 1897 “incident” with Tilden-Thurber seemed pretty cut and dry. Lizzie had stolen two objects of art, was almost arrested for the theft, but settled the matter before it got out of hand. The story appeared in the newspaper briefly; then it disappeared. It was one more piece of evidence that Lizzie was a kleptomaniac–something we all knew. I wanted more than that, if there was more to be found. I wanted to dig into the story like a kid on a beach with a sand shovel.

I thought that if I dug deeply enough then the truth would be revealed and all the stories of the Tilden-Thurber incident, from the arrest warrant to the settlement to the signing of a confession, would be neatly explained to my satisfaction. I would finally know what had happened and it would tell me much about the character of this enigmatic woman. I invite you to come with me as I explore this piece of history that has become so much a part of the Lizzie Borden legend.

The story of the event first ran in a publication called The Bulletin on February 15, 1897. That item being unavailable to me, I embarked on this journey as close to the beginning as I could: reading the Providence Journal’s first newspaper article on the story. Notice how in this front page story, the author uses Lizzie’s new difficulty as an excuse to rehash the crimes for which she was acquitted four years before. In fact, most of the piece is devoted to the murders rather than the Tilden-Thurber controversy.

Providence Journal 16 February 1897

LIZZIE BORDEN AGAIN.

A Warrant for Her Arrest Issued from a Local Court.

TWO PAINTINGS MISSED FROM TILDEN-THURBER CO.’S STORE.

Said to Have Been Traced to Miss Borden’s Home in Fall River.

OFFICIALS LOATH TO FURNISH INFORMATION OF AFFAIR.

The Warrant Was Issued Some Time Ago and Has Not Been Served. It is Understood That Miss Borden Claimed to Have Purchased the Articles and That She Retained Them.

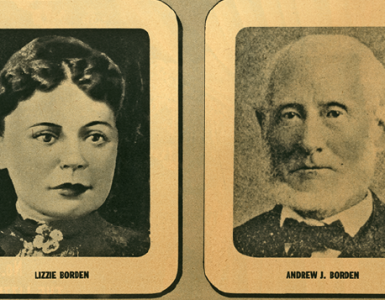

It is but a brief period since notoriety attached itself to Miss Lizzie Borden, daughter of Andrew J. and Abby Borden of Fall River, who were found foully murdered at their home in that city a few years ago. Again is the name of the young woman before the public and this time in a less pleasant character than at the last time, when a story of her alleged engagement was current.

The information published in the Bulletin last evening to the effect that it was alleged that a warrant had been issued against her charging larceny of two paintings from the Tilden-Thurber Company of this city created a sensation. This warrant followed a complaint made against Miss Borden to the proper officials here.

The young woman has been a frequent visitor to this city and a customer of the Tilden-Thurber Company. It is alleged that a short time ago she visited the store and after her departure two paintings upon marble were missed. Investigation followed and the missing goods were tracked to the present residence of Miss Borden at Fall River. This was done after the members of the concern had consulted with officials.

Miss Borden was asked concerning the paintings and declared that she had purchased them in the Tilden-Thurber store. It is said, however, that there was no record of any such sale and it is also charged that the salesman in the department in which these goods were located knew nothing of the purchase claimed. There was some discussion regarding the matter and that members of the company were not satisfied with the statement of Miss Borden is evidenced by the fact that a request for a warrant was made to the local officials.

The alleged affair having occurred in this city the necessary legal documents in the case would have been issued in the Sixth District Court before Judge William H. Sweetland, upon the request of Chief of Police Baker. Being a criminal complaint, the head of the police department would draw the warrant and Judge Sweetland as presiding Judge of the Sixth District Court would place his signature upon it.

Chief of Police Baker will not make any statement concerning the affair. He will not deny, however, that a warrant charging Miss Lizzie Borden with larceny from the Tilden-Thurber Company was issued, and Judge Sweetland, being Judge of the District Court, does not care to make any statement concerning the swearing out of this particular warrant in the District Court.

In fact Judge Sweetland never makes known the contents of the warrants taken before him by officers for issuance.

The ends of justice would be frustrated in many instances were he to make known the contents of legal papers placed before him for his signature.

In the present instance he will not deny that such a warrant as referred to is in existence.

Despite all this, however, it is known that the warrant was issued. It was never served and it is said that the two paintings are still in the possession of Miss Lizzie Borden. Whether a settlement has in the meanwhile been made or the exact reason for the withholding of service of the warrant is entirely a matter of speculation. While there has been no denial that the warrant was issued, officers of the Tilden-Thurber Company, speaking generally, say they either know nothing of the matter or refer inquirers to their associates.

It is said at the store that Miss Borden had been a large purchaser there. The two paintings which were missed and upon the loss of which the warrant was issued were jointly valued at about $100. Officers in this city were employed in the case and it is believed that the assistance of Fall River officials was also brought into the matter.

Mr. Jennings Hadn’t Heard It

Andrew J. Jennings of Fall River who was engaged as counsel by Miss Borden when she was first suspected of murdering her father and mother, and who defended her in the Second District Court at the preliminary hearing of the case, would have nothing to say yesterday when informed that it was reported that a warrant has been issued for her arrest on a complaint charging his former client with shoplifting. That is, Mr. Jennings said nothing to indicate that he had the slightest knowledge of any such offence on Miss Borden’s part, and intimated that he did not believe there was any foundation for the story.

Fall River authorities, including the Inspectors, who are usually detailed to assist officers from other cities in investigating matters of this kind, also stated that they were ignorant of any accusation of the kind. From other sources, however, it was learned that Detective Parker of Providence arrived in Fall River some little time ago and was heard to inquire of a man with whom he left the train where “she” was living at present.

The news printed in the Bulletin created a profound sensation, as does most news which recalls the remarkable assassination of Mr. and Mrs. Borden, and many tongues discussed the details of the crime once more.

A rumor going the rounds is that Detective Parker was in town last week, inquired for Marshal Hilliard, who did not happen to be in the city, and later called a well-known lawyer out of a place of amusement and disappeared with him.

The Borden Murders Recalled

Wherever the English language is spoken mention of the name of Lizzie Borden will bring with it remembrance of a crime – a crime still unpunished – one of the most horrid in the history of this country. On the 4th day of August, 1892, in the Borden homestead on Second street, Fall River, the bodies of Andrew J. Borden and his wife Abby were found. They had been murdered, done to death with an axe or hatchet.

The mutilation of the bodies was fearful. Even after death had come the perpetrator of the double murder had hacked and hewn at the bodies until floor, walls and even ceilings were spattered with the blood of the victims. On the morning after the discovery of the deed the whole country knew of the affair and the police force of the city of Fall River with Boston detectives were working to unravel the mystery which seemed to surround the crime.

Besides Andrew Borden and his wife there resided in the house his two daughters, Emma and Lizzie. The suspicion of the police was directed toward Lizzie, the younger sister. After some days of labor in the direction of preparing evidence, she was arrested. As in every other murder case of prominence where the identity of the criminal is in doubt, there at once sprung up all over the land a general discussion as to the guilt or innocence of the accused woman.

Lizzie Borden was defended at the preliminary trial by her father’s attorney, Andrew J. Jennings of Fall River, and by Melvin O. Adams of Boston. She was adjudged probably guilty and held for trial without bail. The plea for her freedom made at this time by Mr. Jennings was one of the strongest efforts of the case, and was sufficiently powerful to move his associates to tears.

Ten months following were spent by the accused woman in the jail at Taunton. The keeper of the institution was Andrew Wright, the diminutive High Sheriff of the county, who afterwards turned up as a never-failing source of amusement to the reporters from all over the country, who were at the trial at New Bedford. The Sheriff and his wife were old acquaintances of Lizzie Borden and her experiences in the institution were as pleasant as possible under the circumstances.

The trial of the case took place at New Bedford in June, 1893. In addition to the attorneys who represented her interests at Fall River there was associated in the defence ex-Gov. George D. Robinson of Massachusetts, who became senior counsel. The Government case was in charge of District Attorney Hosea M. Knowlton, who was assisted by William H. Moody of Haverhill.

More than one legal reputation was made in this celebrated trial. Of the attorneys, ex-Gov. Robinson is dead. Mr. Knowlton, the chief prosecutor, who held Lizzie Borden as a child upon his knees and with whose children the woman whom he tried to convict of the double murder had played in her school days, is now Attorney General of his State. Mr. Moody is now a Congressman from his district, Mr. Jennings is District Attorney for Bristol county, succeeding Mr. Knowlton as prosecutor. Mr. Adams is in practice in Boston and ranks as one of the leading members of the Massachusetts bar.

The trial at New Bedford lasted about four weeks and during the entire progress of the affair the remarkable nerve of the accused woman never deserted her. Only once did she leave the court room, and that was when the skull of her father, with its great gaping spaces, showing where the hatchet had struck, was made an open exhibit. She was apparently calmest while the jury was out in its final deliberations. Perhaps this was due to the air of confidence assumed or felt by the able ex-Governor and which he imparted to others. From a legal standpoint, the conduct of the case by both the Government and the defence was declared to have been admirable. Certainly the oratorical efforts of the attorney in their closing arguments have seldom been surpassed in this country.

After her release from confinement she returned to Fall River, where she has since resided with her sister. They purchased a residence in an attractive part of the city, but have never been able to entirely escape notoriety. A short time ago a story that Lizzie Borden had become engaged to a young farmer was current, and while the story was denied, it was responsible for additional gossip concerning the sisters.

It was believed by those who remained loyal to Miss Borden during the period of accusation that after her acquittal of the charges there might arise some clue to the real perpetrator of the shocking crime. The years have passed but there is no clue, and the murderer is still unpunished.

That same day, three thousand miles away, appeared this rather brief special dispatch (and introduced to the story the Christmas timeframe for the “crime”):

Los Angeles Times 16 February 1897

STOLE PAINTED MARBLE.

THE NOTORIOUS LIZZIE BORDEN AGAIN IN TROUBLE

A Warrant Out for Her Arrest on the Charge of Shoplifting-Tried for the Murder of Her Parents a Few Years Ago.

[BY THE TIMES’ SPECIAL WIRE]

BOSTON, Feb. 15. – [Special Dispatch.] Lizzie Borden, of the famous Borden murder mystery, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Andrew J. Borden, who were foully murdered, at their home in Fall River, a few years ago, is again in trouble. It is alleged that upon a recent visit to Providence she went into the jewelry store of the Tilden-Thurber Company, and upon her departure two valuable paintings upon marble were missing. The police investigated, and the missing articles, it is alleged, were traced to the residence occupied by Miss Borden, in Fall River. An official complaint against Miss Borden, charging larceny of paintings upon marble, was made in Providence, followed by the issuing of a warrant for her arrest.

Chief of Police Baker will not make any statement, but he does not deny that a warrant charging Miss Borden with larceny is in existence, and Judge Sweetland, Judge of the District Court, will not deny that such a warrant is in existence. It is known that such warrant was issued, but whether the case was settled or not is not known. It is a well known fact that Miss Borden has been a frequent visitor to Providence for the last three years.

“She has visited the store of the Tilden-Thurber Company a number of times, and made large purchases,” said a member of the concern today. “About Christmas time she was there, and called at the store, as well as at other retail places. It was shortly after that that the two paintings were missing, and then the police were notified.”

Lizzie Borden, it will be remembered, was believed by many to be guilty of the death of her father and step-mother, though a jury acquitted her. No strong proof was ever introduced, showing that any one else entered the house before the murders. Lizzie was powerful enough to have committed the crimes, as she was strong as a man. Throughout the trial she showed little emotion and even received the verdict without tears.

Then the next day, again on the front page, appeared the following article, which included the author’s speculations regarding Lizzie’s possible motive for lifting the pieces from Tilden-Thurber, and, for the first time, descriptions of the stolen paintings:

Providence Journal 17 February 1897

THE BORDEN AFFAIR.

Officials and Others Interested Still Uncommunicative.

PUBLICATION OF THE FACTS HAS CAUSED A SENSATION.

Notwithstanding the General Reticence the Issuance of the Warrant is a Matter of Record, Although It Has Not Been Served. – It is Stated That Miss Borden Claimed She Paid for the Articles.

According to the descriptions it is a remarkably pretty piece of bric-a-brac which is the cause of the additional notoriety which has come to Miss Lizzie Borden of Fall River. It is a painting on porcelain perhaps 18 inches in length and half that width.

On the day it was missed Miss Borden entered the store of the Tilden-Thurber Company and went to the upper floor. Here this particular painting was located. Toward the top it assumed an oval shape and was framed in gilt. The other painting which figures in the matter, which has caused so much interest and sensation, was smaller and of less value.

The large painting represented the figure of a young woman in a pose. Its title was “Love’s Dream.” While all connected with the affair are still uncommunicative it is declared to be a fact that but a very short time elapsed after Miss Borden had left the store when the absence of the larger painting was noticed. Members of the company were at once notified and they communicated with the police department.

Detective Parker was sent to the store. Mr. Parker is accustomed to handle cases of a delicate nature and he undertook to trace the lost painting. He visited Fall River one day last week and is said to have been there again Monday.

In the meanwhile the heads of the Tilden-Thurber Company went further. They swore out a warrant against Miss Borden, charging her with larceny. This fact has not been denied, nor will it be by a single person connected with the affair.

And while neither Chief Baker nor Judge Sweetland will talk upon the subject, it is also a fact that the warrant bore the signature of the Chief as complainant, and of Judge Sweetland as having issued the document for the arrest.

Apparently Miss Borden claimed to Detective Parker, who visited her residence at Fall River, that she purchased the painting. It is said to be a fact that “Love’s Dream” is now one of the ornaments of the Borden residence.

But there was no record of any sale at the time of Miss Borden’s departure from the Tilden-Thurber store, and it is a fact that the clerk complained to the heads of the concern of the disappearance of the painting.

From the reticence of all concerned and from the fact that the warrant cannot be located, it is declared that a settlement of the matter has been effected. In that event Miss Borden will not be called before the Sixth District Court to answer to the complaint made in the warrant.

The nature of the settlement of the dispute is, of course, a subject entirely for the imagination. Mr. Parker will not say that the warrant was placed in his charge, though there is little doubt of it. In fact he will not discuss the matter at all. The information that he was in Fall River in company with an officer of that city, presumably Inspector Medley, comes from that city.

As might be expected, the publication of the facts concerning the issuance of the warrant against Miss Borden has created more interest than any happening for a long time. Naturally, this interest is even more intense in Fall River than here.

It has been suggested that the allegation in the case has features not unlike the celebrated Castle case. In that case, it will be remembered, an American woman of great wealth and refinement was arrested in London for shoplifting. The matter was settled, though not without great publicity, after which Mrs. Castle was treated by experts for mental disorder. Eventually she was declared cured.

It is of course idle to presume that the paintings in question were valued by Miss Borden for their pecuniary worth as she is a rich woman. In view of the settlement of the case, which is said to be a fact, it is of course a possibility that the concern were led to see that the claim of the young woman that she purchased the articles was correct even though there was no record of such a happening and despite the complaint of the clerk to the heads of the company.

The issuing of the warrant on complaint of the Tilden-Thurber Company, however, must stand as a fact.

Fall River Officers Knew Of It

Now that the facts have come to light, it was stated on good authority last evening that certain of the police officers of Fall River were not in ignorance of the warrant issued for Miss Borden’s arrest. It was inspected by them some days ago and they were aware that an attempt was being made to trace the pictures to Miss Borden’s house, but inasmuch as the warrant was not to be served at the time they were pledged to keep the matter secret.

On the following day, the west coast newspaper offered their follow-up. What makes this piece significant is that it alleges for the first time in print that Lizzie Borden was, perhaps, a kleptomaniac, thus neatly explaining Lizzie’s motive as part of a larger psychological disorder. Lizzie must have appeared to the author as a person who deserved to have her character attacked when he decided to add this libelous slant to the story. This is the stuff of the National Enquirer, not the Los Angeles Times.

Los Angeles Times 18 February 1897

CAN’T AVOID STEALING

LIZZIE BORDEN ALLEGED TO BE A

KLEPTOMANIAC

Prosecution of the Notorious Young Woman Stopped, Probably for a Monetary Consideration – The Affair Shrouded in Mystery

(BY THE TIMES SPECIAL WIRE)

BOSTON, Feb. 17. – [Special Dispatch.]

It is now alleged that Lizzie Borden, the Fall River woman who figured as defendant in a great murder mystery a few years ago, is a kleptomaniac. It has been suggested that the case has features not unlike the celebrated Castle case, Miss Borden, like Mrs. Castle, being independently wealthy. “Love’s Dream” is the title of a magnificent painting on porcelain which, it is alleged, now forms one of the decorations of Miss Borden’s residence. This painting was missed from the store of the Tilden-Thurber Company in Providence recently. A few minutes after Miss Borden had left the store another painting was missing, too. A warrant was issued charging her with larceny of the paintings. From the reticence of those concerned, and from the fact that the warrant cannot be located, it is declared that a settlement of the matter has been effected. It is, of course, idle to presume that the paintings in question were valued by Miss Borden for their pecuniary worth, as she is a rich woman. In view of the settlement of the case, the firm probably decided that she had purchased the articles, even though there was no record of such a happening and despite the complaint of a clerk to the heads of the company.

Five days after the first Bulletin, the Daily Globe added details regarding the way Tilden-Thurber discovered that a theft had occurred. Note how this article changes the previously reported facts, introducing the female friend who innocently brings one of the stolen paintings in to be framed. The author here has all this information from “reliable sources” and knows the story to be true, apparently, because of “the personality of the young woman concerned.” —-makes me feel confident about the reporting. How about you?

Fall River Daily Globe 19 February 1897

LIZZIE’S GIFT

To a Friend Exposed the Picture Business.

How the Tilden-Thurber Co. Learned

That Their Goods Were Being Sold Cheap.

What Detective Parker Learned in This City.

The Providence Telegram of this afternoon tells the following story of the alleged Lizzie Borden stealing: The non-committal attitude of the Tilden & Thurber Co. as well as the silence of Providence court officials on the matter involving the issuances of a warrant against Miss Lizzie Borden for alleged larceny of two quite valuable paintings from the store of Tilden & Thurber, have made it almost impossible up to this time to get at the true facts concerning the case.

These facts have at last been obtained from reliable sources and can be vouched for as real incidents connected with a proceeding somewhat sensational, not merely on account of the fact of the alleged larceny, but also from the personality of the young woman concerned.

It appears that the firm of Tilden & Thurber had never missed the paintings in question and did not know that they were not in stock in their store until the wife of a cashier of one of the banks in Providence brought one of the pictures to the firm to be framed.

Recognizing it as one of their pictures, an investigation was made by the firm and it was discovered that not only was that picture but also another similar one missing with no charge on the firm’s books for the sale of the same or any indication showing that they had been sold.

The clerks who had charge of the department in which the pictures were placed stated that the pictures had not been sold by them, and they were unable to account for their disappearance. With this evidence the lady who brought the pictures to the store to be framed was confronted. She informed the firm that the picture was presented to her by Miss Lizzie Borden of Fall River, on the occasion of a recent visit made by her upon Miss Borden.

She is a friend of Miss Borden and has frequently visited her at Fall River and as a testimonial of her friendship Miss Borden had given her the picture in question.

Tilden & Thurber then secured the services of the police department and Detective Parker was sent to Fall River to investigate. It was then learned that the second missing picture was at Miss Borden’s residence, and in answer to inquiries concerning it and the picture she had given to a friend in Providence she stated that she had bought them both at the store of the Tilden & Thurber Co., paying $16 a piece for them.

The question of veracity between Miss Borden and the clerks who were in charge of the pictures at Tilden & Thurber’s was thus raised by Miss Borden’s statement and there the matter remains up to the present time.

Tilden & Thurber state, however, that the pictures, or one of them, at least, was valued at $50, and they cannot understand how Miss Borden could have purchased them at the price she states. Miss Borden has been seen with reference to the additional facts but she refuses to talk.

And then there is this sarcastic ditty from the Fort Wayne News on 27 February 1897:

Lizzie Borden, tried and acquitted for the murder of her father and mother, Mr. and Mrs. Andrew J. Borden, in Fall River in 1892, is again in trouble. A warrant has been issued for her arrest, charging her with the larceny of two valuable oil paintings from the jewelry store of the Tilden-Thurber company last Christmas. The missing articles were traced to her home. She has not yet been arrested. Lizzie seems to have been considerate enough not to have taken the building.

Here are some of the “facts” presented in the newspaper articles. You probably noted, as I first did when I read them, that they each presented quite alternative versions of events: the last one being downright mocking. I observed the following:

• The article entitled “Lizzie Borden Again” tells us that there were two paintings on “marble.” A salesman was in charge of selling those paintings, and the two paintings were still in Lizzie’s possession. The paper does say that the exact reason for not serving the warrant is “entirely a matter of speculation.”

• “The Borden Affair” article says that a painting on “porcelain” perhaps 18” in length and half that width was involved, and that the large painting was a figure of a young woman in a pose titled “Love’s Dream.” There was a second smaller painting worth less. The larger one was missing shortly after Lizzie Borden left the store.

• In “Lizzie’s Gift” we are told that Lizzie had given one of the paintings to a friend. The friend is described as the wife of a cashier of a Providence bank. When the banker’s wife brought the item to Tilden-Thurber to be framed, staff there recognized it as one of the two missing paintings. The clerks did not know the paintings were missing until the woman brought the one painting in. She told the store staff that Lizzie Borden had given it to her.

• The LA Times article of February 16, 1893 goes back to the description of the paintings being on “marble.” But an extra twist is added – that Lizzie visited Tilden-Thurber around Christmas time and shortly after the paintings were discovered to be missing.

• “Can’t Avoid Stealing” calls Lizzie an alleged kleptomaniac. The paintings, one a “magnificent painting on porcelain,” had been missing recently. After Lizzie left the store one day the other was missing. The reporter takes a guess that since the warrant cannot be found, maybe Lizzie did pay for the paintings and the store disregarded the salesclerk’s proclamation of thievery.

Even with an awareness of the progression of the Tilden-Thurber story, the tale seemed to be taking on a life of its own and the differences among them as to who, what, where, when, and how leaves us still uncertain as to the truth of the matter. For instance:

• Were the paintings on marble or porcelain?

• Were they discovered right after Lizzie left the store, or later?

• Did Lizzie have both paintings?

• Did Lizzie give one to a friend and was caught when the friend brought it in to be framed?

• Was Lizzie Christmas shopping at the time?

• Was Lizzie a kleptomaniac?

I turned to my beloved Lizzie authors for answers, thinking they would clear this up. After all, they were writing about the Tilden-Thurber incident from the perspective of time and had surely done a great deal of research in preparing their pages. I was both disappointed and confused by what I found.

Surprisingly, Edmund Pearson in Trial of Lizzie Borden doesn’t give the incident many lines. There is a different spin on the story, though, when Pearson says that a lady in Providence brought in “Love’s Dream” for repair. He quotes a letter from Tilden-Thurber that states, “The matter was ‘adjusted’ out of court, and the warrant was never served.” I found it somewhat strange that Anti-Lizzie Pearson would cease writing of this juicy incident without something more. He obviously had nothing more.

Edward Rowe Snow’s chapter on Lizzie Borden in his Boston Bay Mysteries and Other Tales introduces another, and new, entire story within the story. After telling us that this happened in the month of October (with Lizzie wearing a “voluminous sealskin coat,” presumably to hide her booty) he names the salesman as Miss Addie B. Smith. The two paintings disappeared, but the store could do nothing at the time since there was no proof. But in February, Lizzie’s friend came into the store and brought in the larger painting to be repaired, and stated Lizzie had given it to her. Incredibly, Addie “identified the stolen article immediately by its length of about fourteen inches, its oval shape at the top and its gilt frame.” It is interesting that she did not recognize it by the picture.

Snow also gives the full name of the detective as Patrick H. Parker. Henry Tilden, according to Snow, came up with the idea of having Lizzie sign a confession saying she was the murderer of Andrew and Abby Borden. In exchange for this document, the store would drop the charges. Lizzie refused.

After a very dramatic scene where the clock counted down until midnight, as Detective Parker was about to serve Lizzie with the warrant, she changed her mind and typed out:

Unfair means force my signature here

Admitting the act of August 4, 1892, as mine alone.

Lizbeth A. Borden

With a twist that would rival O Henry, the men in the room agreed to not make the confession public until all five of them died. Morris House took the paper to be copied. He explained the situation to the clerk who waited on him, Thomas H. Owens, and swore him to secrecy. However, Mr. Owens at first made a bad copy and saved it, and “as the years went by he watched the papers for any news of the death of the persons who witnessed it. In 1927 when Lizzie died Owens wondered if some news might leak out, but he read nothing. The years passed, and one by one the principals in the case passed away. Owens confidently believed that a revelation would eventually be made, but nothing every [sic] appeared in the papers.”

According to “Lizzie’s Tilden-Thurber ‘Confession’” by Paul Fletcher in The Lizzie Borden Quarterly, in 1952 Owens heard a radio broadcast of Snow’s, contacted him and told him about the confession he had. He asked $100 for the copy. Snow offered $50 and Owens took it.

Edward Radin, author of Lizzie Borden: The Untold Story, hired Ordway Hilton, a well-known handwriting analyst, for his professional opinion on Lizzie’s signature on this confession. Mr. Hilton stated the signature was a forgery; it was too exact and was probably a tracing of Lizzie’s signature from a copy of her will.

In A Dance of Death, Agnes deMille writes that there was no proof of Lizzie stealing the paintings, but the store marked the loss on the books as theft.” It was not until a year later that “a resident of Fall River brought the larger painting in for exchange [emphasis mine].” The woman said Lizzie had gifted her with the painting, and Lizzie was threatened with “exposure and arrest” unless she signed a confession admitting that she alone committed the murders of her father and stepmother on August 4, 1892. Mr. Welch, who was studying the story with deMille, “thought that the story might be a fabrication, and the extortion prompted only by curiosity.”

Robert Sullivan in his book Goodbye, Lizzie Borden wrote that he thought Lizzie probably did lift the paintings. “Remembering the ‘robbery’ which Andrew Borden had first reported to the police only to reject police investigation shortly thereafter, I am inclined to admit the plausibility of the shoplifting episode, but I do not consider it particularly material to the telling of this story.”

In A Private Disgrace, Lizzie Borden by Daylight, Victoria Lincoln makes a change in the story by telling us that it was a caller at Maplecroft who admired the paintings, and Lizzie gave her one. The friend dropped and broke her gift and took it to Tilden-Thurber to be repaired (the name of the store was still on the back of the painting). The friend said Lizzie had given her the painting. Ms. Lincoln writes that, “the plaques had been as expensive as they were ugly.” She does, however, point to an “employee” as a perpetrator of the “fraud.”

Was there a Confession?

One of the leading handwriting experts in the country proclaimed Lizzie’s signature of the confession a forged tracing over the signature on her will.

“Everything you have read about Lizzie Borden is quite factual,” president William H. Thurber confirmed to Joyce G. Williams in correspondence in 1979 and 1980, when queried about “the shoplifting story.” He learned of the incident from his father and his uncle, who were co-owners of Tilden-Thurber when Lizzie’s incident occurred. But does this mean the warrant was factual? Does it include the confession as well?

The original photographic plates that were made of the confession were lost in a fire at the store in 1913, some said. deMille states that the photograph of the confession, the negative, and the original were kept in the store safe at Tilden-Thurber. The “photographer had made a print for himself,” and it was this saved image that Snow and Radin supposedly examined. Not long ago, I interviewed a lady who was acquainted with a relative of one of the co-owners of Tilden-Thurber in 1897. The relative did say that the confession was lost in the hurricane. The store was flooded and ruined the confession that was in the store’s safe.

Was Lizzie a Shoplifter?

In correspondence with Joyce Williams for her Casebook, a long-time Fall River resident and former newspaper reporter, Mrs. Edith Coolidge Hart, had this to say: “There is little doubt in my mind that Lizzie was indeed a mental case . . . Lizzie did what a great many people with money do. She tried to buy friendship and the good times she never had.”

In Rebello, we find a segment of an article from 1992, where Mr. Edward Jennings, the grandson of Andrew J. Jennings, commented for the Brockton Sunday Advertiser. Mr. Jennings had this to say about Lizzie’s rumored penchant for taking things that didn’t belong to her: “Lizzie was a chronic shoplifter. Several years ago after the trial, she was caught shoplifting in Providence. My grandfather got her off, then came home and said, ‘I will have nothing to do with that woman.’”

There was the daylight robbery at the Borden house, in the summer of 1891. Facts pointed to the perpetrator being Lizzie. Emma and Bridget were both at home with Lizzie. Mr. Borden at first notified the police, then told them to cancel the investigation as they would never find the real thief. Perhaps this was a setup for the following summer’s murders. Lizzie could jump up and say that someone broke into the house with three at home and robbed them in full daylight. The daylight robbery of the Borden residence does not quite fulfill the prerequisites of someone diagnosed with “kleptomania,” does it? If Lizzie did commit the daylight robbery in the family home, it would seem that she had a far more important reason to do it than any pocketing of baubles downtown.

Conclusions?

Stories of Lizzie’s shoplifting in Fall River, with merchants instructed to bill Andrew Borden for reimbursement, have trickled down by word of mouth the past 135 years. But what is there in writing? What proof of this was there, or is there? I would think that some kind of hard evidence would be available today – a note or a copy of a receipt billed to Andrew Borden. There has been nothing. Are we to believe this is the only time Lizzie shoplifted and got caught? Or is this simply the first time she got caught? With many students and scholars studying the case for years, one would think someone would have turned up something by now.

Is the Tilden-Thurber episode proof enough for us to say unequivocally that Lizzie Borden was a shoplifter? The warrant was never served so there is no legal document for us to see. The story was never completed in the papers; all mention of it ceases soon after. Perhaps Lizzie did steal the two paintings on porcelain or marble, and paid for them when caught a few minutes after she left the store, or months later when a friend, who visited Maplecroft or was the wife of a Providence banker, brought one of the paintings Lizzie had given her in to the store to be framed or repaired. It is also equally possible that Tilden-Thurber had made a mistake and merely dropped the charges. It is hard to think that this is the simple truth, since it has become part of the popular lore that Lizzie took the paintings and probably bought her way out of the situation to avoid arrest. Could it be that Lizzie Borden is innocent of both the Tilden-Thurber shoplifting and even kleptomania in general? You may agree with me that at least the possibility for both exists.

Works Cited:

“The Borden Affair.” Providence Journal 17 February 1897: 1-2.

“Can’t Avoid Stealing.” Los Angeles Times 18 February 1897: 2.

deMille, Agnes. A Dance of Death. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1968.

Fletcher, Paul. “Lizzie’s Tilden-Thurber ‘Confession’.” Lizzie Borden Quarterly II.4/5 (Fall/Winter 1995): 8-9.

Fort Wayne Herald News 27 Februuary 1897.

Lincoln, Victoria. A Private Disgrace: Lizzie Borden by Daylight. NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1967.

“Lizzie Borden Again.” Providence Journal 16 February 1897: 1-2.

“Lizzie’s Gift.” Fall River Daily Globe 19 February 1897: 8.

Pearson, Edmund. The Trial of Lizzie Borden. NY: Doubleday, 1937.

Radin, Edward. Lizzie Borden: The Untold Story. NY: Simon & Schuster, 1961.

Rebello, Leonard. Lizzie Borden Past and Present. Fall River: Al-Zach Press, 1999.

Snow, Edward Rowe. Boston Bay Mysteries and Other Tales. NY: Dodd, Mead & Co, 1977.

“Stole Painted Marble.” Los Angeles Times 16 February 1897.

Sullivan, Robert. Goodbye Lizzie Borden. Brattleboro, VT: Stephen Greene Press, 1974.

Williams, Joyce G., J. Eric Smithburn, and Jeanne M. Peterson. Lizzie Borden: A Case Book of Family and Crime in the 1890s. Bloomington, IN: T.I.S. Publications Division, 1980.