The unabashed tale of filming a do-it-yourself Borden screenplay in technicolor in the sanctity of your own home.

by Shelley Dziedzic

First published in August/September, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

My year of awakening was 1991. Living a stone’s throw from Fall River in Newport, Rhode Island, during the uneventful Navy wife years from 1972-76, the great obsession that would later come to afflict me lay, mercifully, dormant. Never does a passion arrive when it is convenient, local, or on one’s doorstep. Then came the fateful autumn day in 1991, when Paramount’s version of the peculiar incident at the Borden house found its way to Sunday afternoon’s not-for-prime-time television, a re-run, starring the most unlikely vision of anyone’s axe murderess, Bewitched’s own lovely enchantress. Living in another state, but close enough to think of the location as nearby, I had been dutifully watching the movie while wielding an iron, carefully pressing the wrinkles from the weekly laundry. It was then that the feeling, which many of us know so well, struck like a thunderbolt: Bordenitis—a full-fledged Lizzie-Tizzie—a condition for which there is, thankfully, no cure. You see, the flats had gone cold and I had been ironing some handkerchiefs on the dining room table . . . but I digress.

My year of awakening was 1991. Living a stone’s throw from Fall River in Newport, Rhode Island, during the uneventful Navy wife years from 1972-76, the great obsession that would later come to afflict me lay, mercifully, dormant. Never does a passion arrive when it is convenient, local, or on one’s doorstep. Then came the fateful autumn day in 1991, when Paramount’s version of the peculiar incident at the Borden house found its way to Sunday afternoon’s not-for-prime-time television, a re-run, starring the most unlikely vision of anyone’s axe murderess, Bewitched’s own lovely enchantress. Living in another state, but close enough to think of the location as nearby, I had been dutifully watching the movie while wielding an iron, carefully pressing the wrinkles from the weekly laundry. It was then that the feeling, which many of us know so well, struck like a thunderbolt: Bordenitis—a full-fledged Lizzie-Tizzie—a condition for which there is, thankfully, no cure. You see, the flats had gone cold and I had been ironing some handkerchiefs on the dining room table . . . but I digress.

The very next day, ignoring children, home, and hearth, I made the pilgrimage to the Mecca of all true pilgrims, the Fall River Historical Society, to meet the oracle, Mrs. Florence Brigham. Alas, they were closed. Closed on Mondays. No more final and hope-destroying words could have fallen from the lips of the weary soul who answered the bell that day. I could return on Tuesday it seemed, and so with the heavy heart of a child whose ice cream has just fallen from the cone, I retraced the fifty miles back down Route 95 homeward.

Every passion first bursts forth like a weed from a seed tenderly sown. Florence Brigham was my seed, my portal, and my keeper of the flame. From her patient, and I suspect sometimes weary, re-telling of The Story, came the burning desire to know more, such was her graciousness in taking yet one more acolyte down the old familiar path into the past. Timing is everything in life—and the centennial of the crime was coming in eleven months’ time. During that interval, a cast of characters who would become friends and co-stars of my homemade drama were waiting to be discovered.

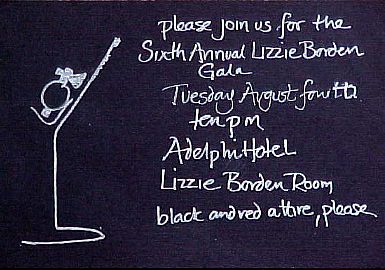

There were an alarming number of visits to the temple of Borden (Fall River Historical Society), and many enraptured moments bent down before the blood-splattered coverlet, gruesome specimen tags, hanks of hair and other relics of the crime of the century. One Saturday night before Christmas week I found myself in the presence of Ed Thibault and Barbara MacDonald at a grand holiday soiree at the Brayton manse on Rock Street. Surely, birds of a feather flock together for in a trice we three were deep in conversation over pear tartlets I had prepared for the occasion, all of us comfortably ensconced on the settee in the front parlor. Having just costumed HMS Pinafore, the closet was bursting with 1890s attire and I was decked out in full regalia. Don a costume and the world will beat a path to your face. It helps also to have no dignity and not mind a particle for those who would dub you “eccentric” or “mad as a hatter.”

Soon after our meeting, the correspondence flew back and forth and plans were made for the upcoming symposium at Bristol Community College. In the orbit of Mr. Lizzie himself, Ed Thibault, the constellation of Kenny Souza, and Debbie Valentine, would soon be complete. And so it was that I found myself on August 4, 1992 playing “At Hame In My Ain Countrie” on the piano at the foot of the staircase at Maplecroft in a green plaid dress with leg-o’mutton sleeves. Bob Dube’s son Michael was giving tours as I arrived suitably attired to pay my respects to Lizzie and to get a longed-for glimpse of Maplecroft’s interiors. After the impromptu hymn-sing, I looked up to see a man pensively listening at the foot of the stairs: “I am Leonard Rebello,” he said—and now the Second Street Irregulars were complete.

In the months to come, Ed’s living room would be home base for many meetings, and the launch pad for projects and ruminations, speculations and re-creations—from real-time experiments with a stop watch (just how long did it take for a person to walk to Sargent’s or Alice Russell’s house and how long does it take to strip out of a waist and skirt, etc.), to birthday outings, to Dedham to see Lizzie’s dogs at the pet cemetery. There was even a picnic for Ken’s 26th birthday which featured The House rendered in cake and butter cream frosting, which Ken dutifully cut with a hatchet. Happiness is having companions on the road to lunacy! With 92 Second Street a closed premises, our experiments in re-creating The Crime were limited to pressing our noses to the window, forlornly looking in like disappointed children and galloping madly about the streets of Fall River, cameras and watches in hand. So the notion of actually filming the foul deeds elsewhere blossomed as a necessity, and The Pear Essentials Acting Troupe was born! I wrote Lizzie the Guilty and Lizzie the Innocent scripts, but we decided the guilty version would be ever so much more fun to perform.

I live in the Pachaug State Forest, about an hour southwest of Fall River—a location that, for the first time, proved a blessing. Driving 14 miles for a loaf of bread has been a tiresome encumbrance over the years, but in this case the remote locale in which Bambi would thrive compensated admirably—not having power lines and screeching cars and every other curse of modern life imposing itself on our 1892 soundstage. Even the small orchard of Golden Delicious apples in my backyard proved admirable stand-ins for those famous pears, at a distance that is, and joy of joys—I have a barn!

The challenge, of course, is in creating the illusion that the interior of a 1979 Garrison Colonial is a dead ringer for that well-known little nest on Second Street. Light switches, electrical outlets, and a hulking great refrigerator would prove the most obstinate illusion-shatterers. With Ken Souza’s expertise as director and film editor at Bristol Community College, he was our natural choice for our own personal Cecil B. de Mille. Ken quickly devised some unique camera angles to avoid the unsightly reminders of the Twentieth Century. With the foresight of having installed a faux wooden kitchen floor, so popular back in the 1970s, at least the floor shots were believable. With some artful draping of vintage towels over the dishwasher and removal of anything smacking of plastic or vinyl and the substitution of yellow ware bowls and wooden spoons and rolling pins, the kitchen was ready for its close-up.

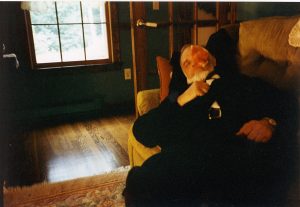

The living room proved a glamorous stand-in for the sitting room crime scene, with a door conveniently situated at the head of the sofa, thoughtfully positioned for optimum hatchet swinging angles. With a few antique props, the set was ready for business. All basements by their very nature are creepy, mysterious places where all manner of bug life and concealed deeds are possible. With the careful construction of a “privy” fashioned from scraps of plywood, a convincing latrine took shape in the darkest corner of the cellar. Having only the movie version as reference, the effect was one of a Girl Scout Camp “earth closet”—but such a dandy spot to lose a hatchet! McCormick’s best red food-coloring and Heinz ketchup was at the ready for special effects in the blood and gore department, and Ed Thibault, starring as Andrew Borden, fashioned quite a convincing “wound” out of layers of saturated paper toweling which we thoughtfully kept in the fridge between “takes.” The smell of the vinegar in the ketchup at close range (literally upon one’s nose) is, in a word, unforgettable. Just ask Ed. With costumes purloined from the convent school production of HMS Pinafore, we were ready—except for the cast of course.

I have always maintained one’s children should be exploited by their parents whenever possible, and so I had no qualms in roping in my 13-year-old to pose as the Kelly maid, and my 17-year-old to dress in men’s breeches and riding boots to serve as Mr. Cunningham, that intrepid bearer of The Bad News to three Fall River newspapers and ultimately the police.

Both darling daughters, quite accustomed to a distinctly bizarre mother who had subjected them to Titanic, Jack the Ripper, vampires, and other un-matronly passions over the years, without demur and without a whimper acquiesced, and their little friends who only went to Little League games and Sunday School thought it all very “cool, dude.” Even Old Jack (our antediluvian white gelding) came in for his share of glory as the vehicle upon which Mr. Cunningham rode down our dirt lane to raise the alarm. Animals are always a plus in any cinematic production.

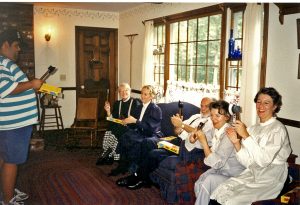

And what are friends for if not to take advantage of? Our piano teacher, Mrs. Lillian Fessenden, donned the spinsterish garb of Alice Russell. Good friend and vocal teacher, Ms. Carol Fiske, clothed herself in the black gown and hat of Adelaide Churchill, complete with her downstreet ensemble of gloves and parasol. Deborah Valentine was resplendent in her Irish maid costume as Bridget Sullivan, along with Ed Thibault as Andrew with beard grown out especially for the spectacle. I was admirably wide fannyed and convincing as Abby, and even Len allowed himself to be “shot” from the back in a cameo as Dr. Bowen. Barbara MacDonald, in true diva fashion without audition, had declared herself the only possible candidate for the leading lady, and had cajoled a willing New Bedford seamstress into producing a most remarkable Lizzie wardrobe.

The summer day of production dawned bright and sunny, and quite possibly as warm as the original. Without a rehearsal, our lines had to be learned scene by scene, with little cheat sheets tacked up in convenient places like foreheads, saucers, and light fixtures, or palmed inconspicuously in moist hands. The hardest part was trying not to crack up while delivering a powerful line like “I can get water from the barn if you want to lock the door Lizzie.” After Ed and I had been summarily dispatched by the hatchet to the Other Side of the Veil, we laughed uncontrollably beneath our stifling blood-soaked sheets as we lay like filleted codfish on the dining room table. My long-suffering spouse, retuning from Navy Reserves, paused momentarily in the doorway, called out plaintively for his dinner as I lay oozing beneath the cloth, and then continued onward without further interest into his man cave to watch the Red Sox as if this were an everyday occurrence. Men.

With compelling if hammy still shots, re-shoots, artsy camera angles, mad improvisations, Wild West antics on horseback, and countless “takes” on scenes where we simply forgot the lines or burst into fits of hysterical giggling, the filming took most of the day. As the sun set in the west, we collapsed over refreshments which included many attempts at fashioning pears into various forms of edibles, not all a total Martha Stewart success.

With compelling if hammy still shots, re-shoots, artsy camera angles, mad improvisations, Wild West antics on horseback, and countless “takes” on scenes where we simply forgot the lines or burst into fits of hysterical giggling, the filming took most of the day. As the sun set in the west, we collapsed over refreshments which included many attempts at fashioning pears into various forms of edibles, not all a total Martha Stewart success.

Exhausted but entirely pleased with ourselves, the crew piled into cars and returned to Fall River, richer for the experience, if not ready for the Hollywood A List. Ken edited and tweaked the raw footage into a semblance of a blockbuster, added an Enya soundtrack and removed all the color to reproduce an Alfred Hitchcock effect. Our official premiere was at the Down Under Aussie pub during the Lizzie Expo in 1994 to a captivated audience. And now, there’s that other version to consider. . . . and August is here again.