a review by Kat Koorey

First published in Fall, 2009, Volume 6, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

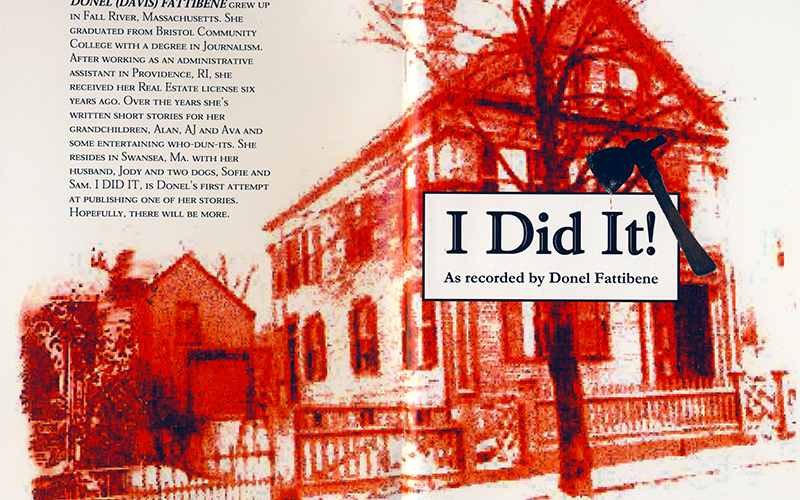

This booklet is eye-catching and attractively designed, and upon examining the cover more closely there is attribution given to Lisa Churchill. She is also named as providing “Editing”—which is curious, as there is no editing apparent within this book. Within the first two pages it is recorded that this is published “On the 137th Anniversary of the Borden Murders,” copyright August 2009. Not knowing what to expect, the thought occurs that the story might be set twenty years in the future, but no—it’s an avoidable math error, one that might dampen initial enthusiasm in the reader. There are other examples of miscalculation in store, such as age of characters and the span of years amongst relations. The author obviously had no one fact-check their work before publishing, which might be a lonely feeling after putting a private work before the public, for sale, without critical assistance, as there are always Bordenphiles willing to critique. There are expert contacts online who are open to a writer on the Borden case, and who would willingly supply some support to those who would deign to utilize them.

This booklet is eye-catching and attractively designed, and upon examining the cover more closely there is attribution given to Lisa Churchill. She is also named as providing “Editing”—which is curious, as there is no editing apparent within this book. Within the first two pages it is recorded that this is published “On the 137th Anniversary of the Borden Murders,” copyright August 2009. Not knowing what to expect, the thought occurs that the story might be set twenty years in the future, but no—it’s an avoidable math error, one that might dampen initial enthusiasm in the reader. There are other examples of miscalculation in store, such as age of characters and the span of years amongst relations. The author obviously had no one fact-check their work before publishing, which might be a lonely feeling after putting a private work before the public, for sale, without critical assistance, as there are always Bordenphiles willing to critique. There are expert contacts online who are open to a writer on the Borden case, and who would willingly supply some support to those who would deign to utilize them.

In her biographical material on the back cover, Donel Fattibene reveals this is her “first attempt at publishing one of her stories.” Well, it is a courageous attempt, as the Borden community of readers is hard to please. The story is enjoyable and diverting: Is it a dream? Is it reality? Is it fiction—or some combination of these? Does the author herself know? If Emma came to her in dreams (which is the premise), and asked that this story be told, maybe Emma herself was an imposter, or even possibly leading the dreamer astray by confiding a fabrication.

The conditions under which the ‘facts’ are revealed are remindful of a simple plot devise that is awkwardly obvious—the class of fact/fiction one might dub as “And Then She Woke Up.” This is not to be confused with “Once Upon A Time”: at least in the latter case one knows that it is a fairy tale in which one is investing their time. If you don’t believe in the possibility of ghostly visitation through dreams, or that Emma Borden would ever claim to the author that “Mrs. Brigham was not susceptible to her aura” and that obviously Ms. Fattibene was, then this booklet reads like a fairy tale. If you can suspend your disbelief, it is actually entertaining and somewhat imaginative: at least one is warned that the writer does awaken.

The author adds just enough of the mundane, the right little twist that is revealing of human nature, a clever nuance here and there that develops a character, allowing reality to intrude in spite of the story—these are the best bits in the tale. An example is first come by on page one, as Emma explains why she did not reveal these truths during Lizzie’s trial: “However, I almost related my saga to Dr. Bowen! His reply was that ‘he would not listen as he felt if he did not know, he could not tell—so to keep quiet to save Lizzie.’” She demonstrates an inventive imagination when revealing Borden family life, as told from Emma’s perspective, and is insightful in her psychological profiles of its members, extending this talent even to their relatives’ point of view, while also exposing how a small town atmosphere prevailed in old Fall River, before and after the tragedy. However, there are elements of the familiar themes of Victoria Lincoln and Frank Spiering, with a dash of Arnold Brown’s illegitimate child, including Muriel Arnold’s idea of the murder weapon being dropped into the Quequechan, along with the very title of I Did It! reminiscent of O.J. Simpson’s book—which leaves one wondering if Ms. Fattibene borrowed from, or was influenced by them.

By page eight, there begins a serious accumulation of misstated facts that multiply until the finale, but these do not have to mar interest in the story, if one can suspend judgment, and concentrate on the quality of the tale. Abby Borden is depicted as a hateful and hating person, and Andrew as muddled with senility. Abby is forced to choose between loyalty to her own half sister and family, and the Borden girls who are her husband’s daughters—she chose her blood kin, and consequently dies by the hand of the other, as the primary victim. There is motive here, and the beginning of a rationalization of this premeditated murder: “Jealousies are tampered deep down inside until one day, one little thing sets it off and revenge is born! . . .If you could see the hatred pouring out of Abby, you would wonder why neither of us did away with Abby including Papa long before it happened.”

By page thirteen, any reader serious about the Borden murder case may be shocked by faulty assertions, although they are bold and creative. Soon after, the writer mistakenly steps out of the persona of first-person-witness, which is a serious flaw because it is a reminder we are only observers and allowing ourselves to be manipulated. Perhaps if there is a second printing, all these errors can be remedied.

Once we are delivered back into first person narrative, the spectacle of the killing of Abby has an immediate impact and intensity. But soon, again, there is disappointment in how easily the author dispenses with an unruly problem of blood on the attacker: simple—“…it wasn’t much blood and I would be able to walk out and no one would notice if I hurried away quickly.”

Earlier, a similar foul was committed by the author, and this is the one that cannot be forgiven within this offering, if indeed we had already decided to overlook errors in grammar, punctuation, misleading facts, unsupported conjecture and conclusions jumped to, all of which suggest an initiates’ lack of scholarly sophistication. The front door locks are pivotal to the true story of how the crime was committed, and to this re-telling as well, but what we find here is a simplistic coverage of a fundamentally major problem—these locks, and especially the bolt, have to be dealt with when the claim is made that the killer entered here and had hoped to retreat through here. This puzzle cannot be brushed aside as no matter. If the author can’t get the villain in the house through this door (which she chose) utilizing a reasonably adequate solution, then the story has failed. If Andrew could not enter through this bolt, neither can we. In essence, Ms. Fattibene is trying to solve a ‘locked-room mystery’ by simply declaring the room was not locked! In your dreams!

By the finish, we are aware that the storyteller, Emma, has been gripped by an obsession for over one-hundred years, to convey her version of what really happened that day in August (“It had to be 100 degrees outside!”), in old Fall River of 1892, when the Borden folks were slaughtered. So desperate to impart the ‘true facts’ that she has been stalking the dreamer, Donel Fattibene, trying to gain her awareness: “I have sat in the Fall River Historical Society, Maplecroft and the Second Street home, and tried to come through their séances and never found someone to hear me—until now! This is my last chance to be believed!” Why this is the “last chance” is not forthcoming, although the author admits she had waited many years before advancing this version, and so has “done a terrible injustice to Emma. She needs to be able to have her peace, and by publishing this for her, she can finally do so!”

This is the point where the reader becomes aware again, and wonders: Was this a dream? Whose dream? Even Emma, within the dream, states she feels she was in a dream-state the day of the murders. Was it really Emma telling this story, or an otherworldly imp pretending to be Emma Borden, fooling Ms. Fattibene? Is Ms. Fattibene fooling us? The very fact that we are left pondering these questions proves this book as worthy.

Fattibene, Donel

I Did It! as recorded by Donel Fattibene, A Privately Printed Edition, Swansea, Massachusetts, August 2009. 54 pages PLU 1201, $9.95. Available Fall River Historical Society, Rock Street, Fall River, MA.