by Tim Evans, producer

First published in October/November, 2004, Volume 1, Issue 5, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

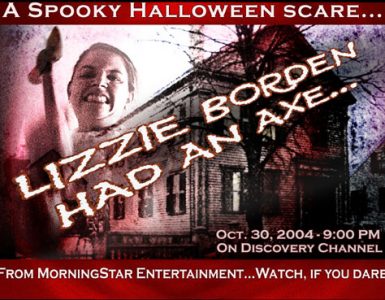

LIZZIE BORDEN HAD AN AXE is a one-hour television special that applies modern forensic techniques to the Borden Murders of 1892. It aired on the Discovery Channel on Saturday, October 30, 2004, at 9:00 pm.

For most of my adult life I have been a documentary producer. It’s the perfect job for someone with Attention Deficit Disorder. I’m assigned a topic, I read prodigious amounts of material in an attempt to become an “instant expert,” and then I get to talk to people who are the real experts. In three months, I’ve usually assembled all the possible visuals on the topic, edited the whole thing into a 44-minute-and-30-second show, and I’m ready to move on. I’ve produced documentaries on subjects ranging from the Abominable Snowman to the origins of Christianity, from haunted Caribbean islands to the life of Billy the Kid. I know a very little about a lot of things. My knowledge base is like a swamp. Or perhaps a better metaphor is an alluvial delta: very, very broad, but not at all deep. And with lots of strange things growing in the corners.

And one of the strangest, of course, is Lizzie Borden. When I got the assignment from the Discovery Channel, I figured it was a pretty standard show: crazy lady, forty whacks, blah blah—shoot a couple of re-enactments, talk to a couple of crime experts, move on. But the Lizzie Borden story is such an enigma, with plot twists and turns that defy explanation that I found myself hooked by the story.

One of the most wonderful parts of Discovery Channel’s show is that we got to actually re-create the crime with two of the best criminal investigators in America today. We laid out the crime scene with re-enactors to try to work out the crucial sequence of events. We created a “sound analog” of the murders to see whether anyone could actually have heard the crimes being committed. And, most importantly, we sprayed Luminol—the nearly magic forensic blood tracer—on various parts of the house to discover disturbing new evidence.

But when I found myself splitting open a skull with a hand-axe —on camera—I knew that I had perhaps gotten a little too deeply into my subject. Lizzie will do that to a person.

The result of this last event will NOT appear in the prime time documentary, mostly because it’s simply too grisly to discuss on prime time. But now I know exactly WHY the murderer gave Abby Borden 19 whacks in the back of the head. And it’s not what you think.

After being assigned the story, I immersed myself in the world of Lizzie Borden, reading everything I could, examining every possible suspect. Like most people, all I really knew in the beginning was the rhyme—so even finding out that Lizzie was acquitted was news to me. But once I’d gotten a good handle on the various texts and theories, I began to line up the interviews, and was fortunate to get some of the best Borden-ites (Bordenistas?) in the country.

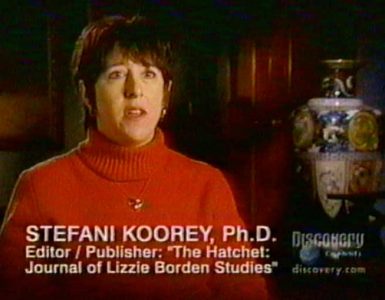

Stefani Koorey and Kat Koorey are not only the editors of this publication; they are some of the nicest and most knowledgeable people on the planet. They gave our show access to every piece of Lizzie material they had, and helped our team get in contact with whomever we wanted. They are also both great interview subjects, attractive, smart and funny, which is a rare and precious combination for a medium that thrives on short sound bites. We also lined up incredible interviews with Bill Pavao, former director of the Borden House Museum, and Len Rebello, whose book Lizzie Borden: Past and Present is a treasure trove of Borden minutiae. William Masterson, author of Lizzie Didn’t Do It, graciously offered to drive down from his home in Vermont to join in the interview. It was an all-star cast for Borden aficionados.

We shot our interviews in the beautiful and historic mansion that houses the Fall River Historical Society. Michael Martins has the unenviable job of running the Society. He is quick to point out the importance of Fall River not only to American history, but also to world trade in the 19th Century. The city was the largest producer of cotton goods in the world, it was the center of trans-Atlantic trade for decades, and at one point in history Fall River, Massachusetts may well have given Boston and even New York a run for their money for the title of “Most Important City in America.”

No one cares. All visitors to the Fall River Museum want to see is Lizzie Borden. Which makes his offer to help our production all the more gracious. Michael Martins—along with many residents of Fall River—finds Lizzie Borden a little too much of a headline-grabber for his tastes, but he not only agreed to be interviewed, he gave us access to the Society’s extraordinary collection of Lizzie Borden artifacts.

The hatchet that prosecutors say did the deed—the Society has it. The sheets Abby Borden was carrying when she got her “forty whacks”—the Society has them. Even the bloodstained headscarf Abby was wearing is carefully preserved in the collection. Some of this stuff is never displayed. None of it has ever been shown on television before. For a TV producer, this was a gold mine.

For a crime investigator, this was simply the Evidence Locker. That’s where Tom Lange and Tom Mauriello came in. Our show began with the premise that we might be able to apply modern forensic tools to this century-old crime—sort of a CSI: Fall River. Tom Mauriello teaches Criminalistics at the University of Maryland, and wrote the textbook that is used in every major university crime department. Tom Lange is a former LAPD detective famous for breaking the O.J. Simpson case. Both of the Toms were excited by the prospect of investigating the Borden murders. But neither was prepared for the wealth of materials that still exist.

When Michael Martins brought out the physical evidence, he insisted that we wear gloves. Lange and Mauriello were used to this sort of thing—I wasn’t. I felt uncomfortable even breathing on the artifacts. Tom and Tom looked at the stuff with a practiced eye. They noted the angle and spatter patterns of the ancient blood on the sheets. They examined the hatchet head—with its broken handle—and quickly spotted apparent vice marks that might have held the hatchet in place in 1892 while someone broke it. Mauriello had no problem popping the handle out of the iron head, just to see if it could be done. And when Abby’s scarf was brought out, Mauriello was the one who quickly decided to compare the cut marks with the hatchet head. While the cameras rolled, Lange held the hundred-year-old scarf out flat, while Mauriello attempted to insert the hatchet blade into a bloodstained cut. I gasped and nearly ruined the shot—it was a near-perfect fit.

But even this discovery was nothing compared to seeing the Koorey sisters examine the same axe. It was fascinating to watch two experienced cops at their job. It was even more fascinating to watch two true aficionados handle and examine what can only be described as the Lizzie Borden Holy Grail. And the difference in their reactions was enlightening as well. The cops simply said, “Interesting, but it doesn’t prove anything.” Kat Koorey summed up the Bordenistas approach when, after handling the axe head in a moment of two of silence, finally breathed: “It’s beautiful.”

To get a better idea of the actual crime, we made our way to the Borden house itself. The owners have done an amazing job keeping the house as authentic as possible. To the unpracticed eye, the house looks exactly as if it were still 1892—as if Abby and Andrew had just stepped out, or as if Lizzie were just about to walk down the stairs with a mischievous grin and a surprise behind her back. Lange and Mauriello were both a little skeptical of the restoration—as investigators, the seeming authenticity of the house only covered up the actual crime evidence. If they had their way, I’m sure both of them would have loved to strip the place down to the floorboards and submit each molecule of wood and fiber to DNA analysis. But short of that, they still had plenty to work with. Tom and Tom examined each room, walked the path of both victims and murderer, and used re-enactors to replicate the crime scene photos.

One particular piece of testimony bothered both men. Bridget Sullivan claimed she had been washing windows outside when Abby was murdered. But it’s a small house. Mauriello and Lange both wondered: “Wouldn’t she have heard a 200 pound woman fall to the ground?” So we put the question to the test. We placed a camera case weighing 200 pounds in the bedroom where Abby was killed. Then we placed Tom Lange and a decibel register by the window where Bridget claimed to be, and dropped the 200-pound case.

The answer was immediately clear, but it wasn’t good enough for Lange. Yes, we could see the result with a large case, but would a human body really sound the same? No, of course not. If we were to do this test right, we needed a body. One that would drop face-first to the floor multiple times—enough to get a clear answer AND get a good take for the camera.

Well, there were no bodies stupid enough to agree to this, and being the producer, I had to take it upon myself. I placed a 25-pound sandbag on each of my shoulders, raising my 160 pounds to the approximate weight of the large-and-lovely Mrs. Borden. Then I fell face first on to the floor. Then did it again. And again. I’m well aware of the importance of getting a good take, but I began to get suspicious when it seemed that both Lange and Mauriello were giggling when they said we needed yet another take.

The result, however, (besides bruised knees) was a surprising refutation of Bridget Sullivan’s court testimony. But of course, you’ll have to watch the show if you want to know what we actually discovered.

The investigation got really spooky when we turned to the basement. The enormous underground area has not been restored at all—in fact, it’s pretty much as it was a hundred years ago. The “water closet” had been covered over, and the floor has been cemented, but there is still much that has been unchanged since a police inspector saw Lizzie Borden doing something mysterious down there in August 1892.

We had brought along a substance called “Luminol.” It’s a chemical compound that makes bloodstains glow bright blue, and is used regularly by crime labs. It’s especially useful when a crime scene has been covered up—even bloodstains that have been washed until they are invisible will glow when sprayed with Luminol. However, we weren’t sure it would work at all, since no one has ever used it with blood stains this old. Tom Mauriello had called the Luminol company, and they said they had used it once on bloodstains from World War II. But stains over a century old? They couldn’t guarantee we’d get any result.

Mauriello mixed the chemical compound in the Borden basement. It’s a caustic compound, which required us all to wear eye protection and gloves. The room had to be dark in order for the fluorescence to show up, so the entire basement was bathed in an eerie red light. Mauriello and Lange began to spray the substance at strategic spots around the basement. Then we turned off the red light, and waited for a reaction.

“Oh my god. Look at this! Look at this!” Mauriello snapped on the red light and rushed to the ladder we had set up. On the ceiling of the basement—just below the spot where poor Andrew Borden had his head split open—a glimmer of blue light could be seen.

Andrew Borden’s blood—112 years old—dimly glowed in spots and patches that had dribbled down through the floorboards of the historic house.

We had proven that Luminol worked on bloodstains that were over 100 years old. Subsequent stains showed up in other spots throughout the basement. Connecting these bloodstains helps to prove a sequence of events that we think points to the actual murderer of the Bordens. Again, watch the show if you want all the gory details.

But no details were gorier than a test I devised once I’d returned to Los Angeles. Tom Lange had made the point that the hatchet might be the key to the murder. Using new microscopic techniques, Lange believed that we could match the minute striations of the hatchet head with microscopic scratches on the Borden’s skulls—much like a ballistics test on a bullet. The L.A. Coroner’s Office agreed to show us how this could be done, if we could bring them the skull and the hatchet.

But since Abby and Andrew’s skulls were buried in Fall River’s Oak Grove Cemetery (at their feet, apparently, after they’d been shown off at the trial), we needed a substitute skull.

And here’s where—in the interest of science—I crept up behind a head and bashed it in with a hatchet.

A human head was out of the question, sadly. So my crew and I did the next best thing. We used a pig’s head. A hapless production assistant bought two sow’s heads from a local butcher and brought them to our production offices. We set up a small studio in the garage, with the pig’s head front and center in the camera. Then I gave it forty whacks.

Actually I only gave it one whack. But, damn it, I barely even dented the pig’s head, and there was quite a bounce to the hatchet. Flesh, bone and brain matter have a lot of “give” and it didn’t seem like I’d done much damage. So I gave it another whack. And then another. Another. Another! It took eight whacks before it was clear to me that I’d actually broken through the thick skull and caused enough damage to show up in a forensic test.

And suddenly, I was in Fall River, in a bedroom, with a prone body before me, and I realized why the murderer gave Abby Borden 19 whacks, and gave Andrew 10. It’s got nothing to do with familial rage or maniacal fury—it’s simply not easy to whack open a head with a hatchet. You need to do it multiple times to be sure the job is done right And the skull I whacked was just sitting there, not screaming or running or begging for mercy!

The pig-whacking incident doesn’t appear in the film. The L.A. Coroner’s Office easily showed that the striations on the hatchet matched the striations on the pig’s head, but since the Borden’s skulls are not available, the entire test didn’t really tell us much. And even if the Borden’s skulls were available (which the city of Fall River has made it very clear they will NOT exhume), the evidence would still be inconclusive. The hatchet might or might not be the real murder weapon, but it still wouldn’t tell us who did the deed. Like much of detective work, we had gone down a blind alley.

Fortunately, we had more than enough forensic material to create a television special and to develop a new and compelling theory for the Borden murders. Watch it on the Discovery Channel on the Saturday before Halloween.

As for me, I had an insight into the Borden murders that very few have ever experienced—the feel of the hatchet in my hand . . . the anticipation as I swung it high . . . and the peculiar emotions that come only when you feel an axe bite into a skull—and splatter pork all over your best shirt.