by Mary Elizabeth Naugle

First published in August/September, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

When considering the famous Borden family menu, I have always wondered which was worse: eating the boiled mutton in any of its various incarnations or cooking it? Boiling the mutton to begin with would have taken from three to four hours—not the happiest way to spend a muggy Sunday in August. According to The New England Yankee Cookbook, even the traditional “‘Boil dinners’ were always served once a week from early fall until late spring.” If even the quintessential boiled dish was suspended, its poor cousin should have been as well. In addition to its violation of custom, the venture would have added to the already oven-ish conditions created by the last week’s heat wave. Remember that the Bordens were without electricity and therefore without fans to exhaust the hot rooms or bring in cooler air. So poor Bridget would have been slaving over a hot stove, boiling the smelliest meat on earth. And the rest of the family would have smelled it along with her—that day and for days afterward. Smells have a way of lingering in humid unventilated rooms. Window washing might have made for a welcome change of air. For that matter, so might a trip to the barn.

However, no one has ever mentioned a second possible scenario. Bridget could have resorted to one of the “convenience foods” of her day: canned boiled mutton. And, for all we know, she did. There is, after all, no account of her boiling a joint of mutton, only of her having served it. We tend to think of convenience foods as a recent innovation, from the T. V. dinners in the 50s to the microwave dinners of the past thirty years. Nevertheless, the Victorian Age saw the beginnings of convenience foods. Factory canning began early in the century, and the invention of the “stamped can” in 1847 made the hitherto slow process of tin-smithing into an efficient and affordable one. By the Civil War, soldiers were able to carry the first ration-kit-tinned meats into battle. When an even more effective “shaping and soldering” machine was displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, canned meat and vegetables had truly arrived.

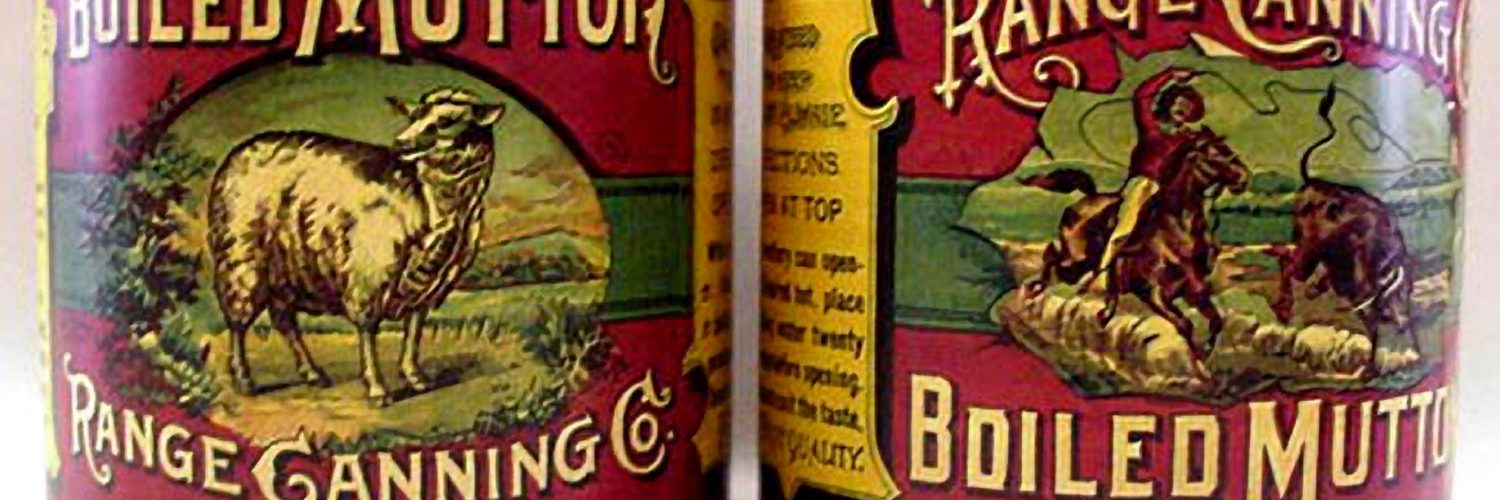

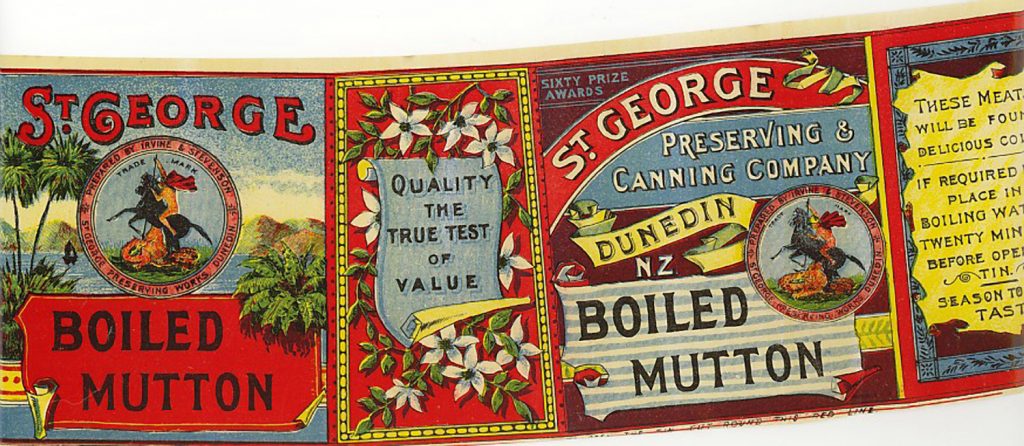

The directions must have seemed wondrously simple: If required hot place in boiling water for twenty minutes before opening tin. Here is a Range Boiled Mutton label from 1890. The Range Canning Company of McKavett, Texas, manufactured the brand. This can, of course, would have done some traveling to get into Bridget’s kitchen. Much nearer to home was the famous B&M Company (the letters stand for Burnham & Morrill rather than for Boiled Mutton or its aftermath) of New England, founded in 1867 and including boiled mutton among its initial offerings. The B&M Company still thrives, but on their baked beans, not their mutton. Mutton, especially canned mutton, has fallen out of favor in our ain countree:

Erica Rosa of the Livestock Marketing Information Center in Lakewood, Colo., near Denver, traces the decline of mutton in the United States to the canned mutton sent overseas to help feed G.I.’s during World War II. They hated it, she said, and ‘when they came home they said they never wanted to see lamb or mutton on the table again.’ Poor cooking techniques and inadequate distribution have also hurt, she said.

As a result, only one factory still produces mutton in the United States, and that mutton is slathered in a Kentucky barbecue sauce. India produces a popular canned curried mutton. Only Australia continues to take its mutton plain and boiled—but then, they eat vegemite sandwiches too. Uruguay has the dubious distinction of producing a mutton that came in at number seven on “The 8 Worst Convenience Foods” list. It is sadly dismissed in the following manner:

Guycan Corned Mutton with Juices Added (Bedessee Imports): The best thing about this Uruguayan canned good is the very pouty-looking sheep on the package label — he seems to be saying, ‘Go on, eat me already.’ The second-best thing is the presence of both ‘cooked mutton’ and ‘mutton’ in the ingredients listing, which would seem to have all the mutton bases covered.

The “spam, spam, sausage and spam” ingredients label does nothing to help the mutton cause here. The fact is that mutton is a gamey meat in a country that now shuns game. The rest of the world may take mutton, but we’ll take beef.

But the Bordens still took mutton. Here’s hoping it and its attendant broth came straight from the can. For Bridget’s sake.