by Stefani Koorey, PhD

First published in Spring, 2011, Volume 7, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

The public and private worlds of Lizzie A. Borden have always been the stuff of legend and myth. So few factual details have surfaced before now that previous authors tended to lean their works towards fiction in order to flesh out her story and make a decent page count. What they created is an unfair and terribly inaccurate portrait, and one that has continues to be enlarged by gossip, theory, and innuendo.

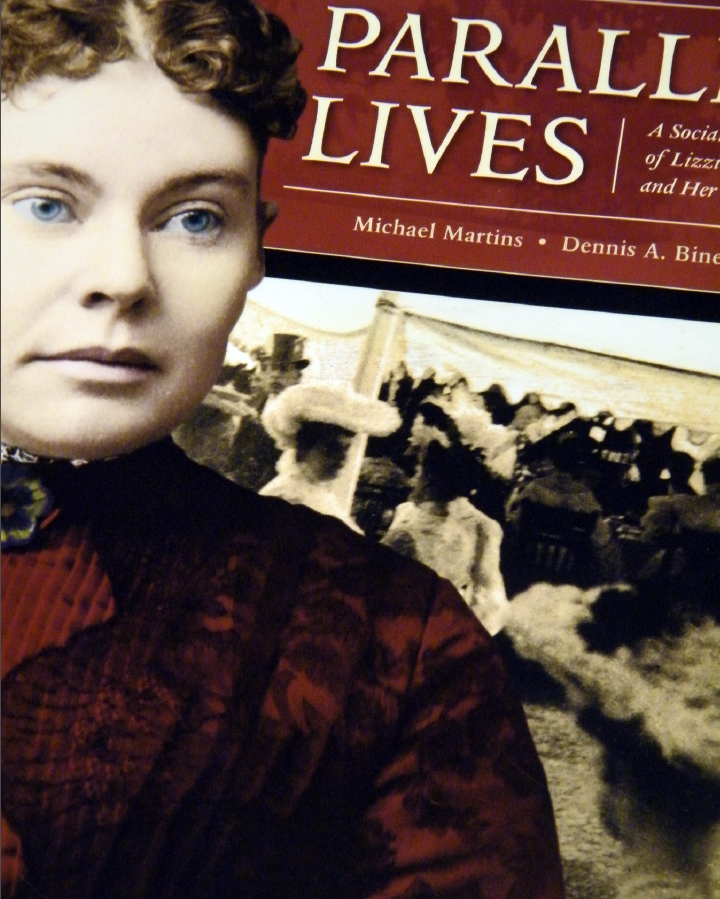

All of this changes with the publication of Parallel Lives: A Social History of Lizzie A. Borden and Her Fall River. Michael Martins and Dennis Binette, curator and assistant curator for the Fall River Historical Society, were the perfect pair to tackle this subject matter. By sheer detective work, they performed the remarkable feat of uncovering material that has been held in private collections and never before shared with the public. In all honesty, this book could not have come from anyone else. These “history hounds” sniffed out the truth of Lizzie A. Borden, and carefully and lovingly crafted a lush epic that places the reader squarely within this remarkable story.

On April 27, 2011, I sat down with Michael and Dennis for their first lengthy interview on the writing of Parallel Lives. It was not the first time we had discussed this city or its most famous citizen, as we have had ongoing conversations about these subjects on hundreds of occasions.

The 90-minute interview was recorded on a digital voice recorder and what follows is an exact transcription of that talk.

HATCHET: Tell me about your process if you can about working on Parallel Lives, from inception to how it ended up becoming organized.

MARTINS: Did it ever? Well the process is kind of like pulling at a stray thread where sometimes you pull at the thread and it breaks and other times you pull at a thread and the whole thing starts to unravel. So that is sort of how it worked.

HATCHET: You unraveled something, or you raveled something?

MARTINS: Unraveled. You start pulling at a thread and the fabric begins to unravel.

HATCHET: So it existed and all you had to do was unravel it?

MARTINS: Unravel it and figure it out. I mean obviously there were very obvious points that we wanted to go with. There were very obviously certain people that Lizzie knew, or certain aspects of her life that we knew about so it was simple enough to follow those leads. But then you had to look beyond the obvious and follow leads that most people didn’t know existed.

HATCHET: What kind of tools did you use to follow leads besides say a telephone and an email system? Did you use online sources?

MARTINS: As far as contacting individuals?

HATCHET: Or to try to figure out everything.

MARTINS: We did some of it online, sure, but I think a lot of it was making personal contact with people who had the material we were looking for.

HATCHET: Well, I noticed that sometimes, Dennis, you would be online with Ancestry and New England Ancestors, and things like that. Was that for this book, or a completely different project?

BINETTE: A lot of that was for this book, but it was mainly rounding out information that we had already found. We used a lot of online genealogical resources to fill in the blanks. One look at the book and you know that there is a lot of genealogical information buried here and there, throughout the text, giving background on everybody that’s mentioned. And once we had the framework, with all your key characters, its finding out who they were and where they came from, who there parents were, and what their stories were, a lot of the genealogical resources were good at helping us to round out stories that we were sort of discovering along the way and that we knew were there. What Michael said about unraveling, we started with a given, we knew what we had to work with, and we knew what we were trying to do. And as things moved along and we researched based on the information that we had to start with, we started to find that there were other avenues that could be pursued, so we kind of went along those routes to see what was there, and that’s where we kind of stumbled into—in some cases stumbled, and in other cases went looking specifically for—other individuals that really had never been characters in the story before. In finding out about them, we in turn found out about other characters that were never really part of the story before.

HATCHET: So interviewing real live people about stories of their families, and then you found that there was someone else involved, or someone . . .

MARTINS: Well, in many cases it wasn’t even live people as much as it was maybe diary notations or notes or letters that would sort of give you a clue. And in many cases we didn’t have a surname. We had a name.

BINETTE: Or a nickname.

MARTINS: Or a nickname and then you had to figure out who could this possibly have been. So we had to follow that until we found the right people, and they’d say, “oh yes, this is so.”

HATCHET: Well, I found it incredibly crazy complex where people named their children the same name, and then generationally you’d have a John somebody and then three grandsons later there was another John, same name. How did you navigate those kinds of complications—the way people named their children?

MARTINS: Well, depending on the family, there were certain families that consistently followed a pattern, so that you knew, for example, that with the Braytons and certain branches of the Borden family, when Sr. dies Jr. becomes Sr. and the III become Jr. There were certain families that consistently did that. One way to follow it is to look at the wives. But if two people had a wife named Mary, then that makes it confusing too. But of course, if you didn’t know that, it would have made it that much more difficult.

BINETTE: Right. But in tracking their stories that’s the easiest way to do it, knowing which of that family married what families. Actually tracking it through the wife’s maiden name is the easiest way to separate the generations.

HATCHET: I see.

MARTINS: It just makes sense. Because the maiden names in most cases are all going to be different. So even if you are going to have three John Braytons, or John Summerfield Brayton, then you know that their wives had different surnames.

HATCHET: And then you have the different spellings: Phebe, Phoebe.

MARTINS: Exactly. And those oftentimes changed back and forth. For example, Ladowick Borden.

HATCHET: Yes, I wanted to ask you about that.

MARTINS: Ladowick Borden. In all the texts he appeared as Ladowick Borden. But he clearly signed his name Lodowick Borden, L-o-.

HATCHET: What’s his tombstone say, do you know?

MARTINS: It’s very very eroded. It’s difficult to read. But it looks, and we’ve done rubbings, it looks much more like an O than an A. In the family, the family will tell you it’s Lodowick. And in their records it appears as Lodowick. However, in everything else it seems to appear as Ladowick. But he clearly signed his name L-o-.

HATCHET: So in some cases the book is sort of setting the record straight, even just in terms of very small facts and pieces of information.

MARTINS: Well, we tried to set the record straight in a number of cases and documented anything we could possibly document. So there’s something to go back to to justify why we said what we said.

HATCHET: And there is a lot of human interest in it as well, I mean, it is not just the rich or the mill worker, it’s a combination of both stories. But there is human interest on both sides with disasters that befell families, whether it was their own doing or whether it was a fire situation or . . .

MARTINS: The sleighing accident.

HATCHET: Or the sleighing accident, boat accident or . . .

BINETTE: I think that a lot of the content that’s not related to Lizzie Borden in Parallel Lives is meant to create . . .

MARTINS: An atmosphere.

BINETTE: An atmosphere that a story can take place in. Really it’s putting a world around Lizzie Borden’s story. It’s giving you, not just the headlines, it’s giving you what they were talking about in the next door neighbor’s house, it’s giving you what happened to the people that she saw playing in the yard, what did it smell like when the downtown was burning and she looked outside and saw a glow in the sky? It’s that kind of information, in a lot of cases. It’s painting the picture of Fall River from the 19th to the early 20th century, and . . .

MARTINS: Fall River as she would have known it.

BINETTE: Fall River as she would have known it. It’s pulling apart the lace curtains and seeing the city.

HATCHET: You have a lot of information about land transactions and business dealings, and some of them are brand new and interesting in their own right just in that exist. It sort of shows her as having to be involved in a lot of business because of her . . .

MARTINS: She was clearly involved in business transactions. She knew what she owned. I mean there have been a lot of cases, and certainly I’ve known a number of maiden ladies of good family who really had no sense of what they owned. And Lizzie had a hand in it. Charles Cook, I don’t think, acted completely on his own when it came to managing her affairs, or Emma’s for that matter.

HATCHET: I didn’t get a sense of that either from the story.

MARTINS: I mean, she clearly knew what she was doing.

HATCHET: Which makes her a more, not only, well-rounded, but sort of an interesting take on her. She’s not so help-less, as they might have made her be—as some recluse, helpless woman whose a victim of her life.

MARTINS: She was certainly vulnerable.

HATCHET: Yeah, but that’s different.

MARTINS: But that’s different. But I think she knew exactly how her affairs were being managed. In some cases, I suspect, there were instances when she was taken advantage of, I think we know that. But I think she had a pretty good handle at what was going on.

HATCHET: Do you think Emma did as well? Or did she more depend on . . .

MARTINS: No, I think Emma was very sharp. I think there is no doubt that Emma knew exactly what she was doing. In fact, I think that everything Emma ever did was extremely well thought out.

HATCHET: People are going to want to know certain huge missing links. Not necessarily that the book touches on them, but the huge missing links of why did Emma leave? A missing link as to, of course not the murder because you state you are not investigating the crime . . .

MARTINS: No, that doesn’t come into it.

HATCHET: No, it doesn’t come into it. But the Nance O’Neil relationship, her private life sort of exposed and her friendships, and these missing links are somehow, I don’t know, but because they are such a private story, to find out any information about these things is a big big deal to people interested in the story of Lizzie Borden. And you seem to unravel some of that.

MARTINS: Well, with some of that it was just a matter of looking.

HATCHET: Was it something anybody else could find? Or was it something that because you were the Historical Society you were given entrée to that?

MARTINS: I think that the fact that the Historical Society was undertaking the project made things considerably easier. Because clearly no one was going to profit from this, it was being done by the Historical Society, with no individual that was going to make any money on it, and we worked very closely with any of the families that gave us access to their materials, and I think that in most cases, they felt that the time had come to make some of this information public. Not that it could really vindicate Lizzie, but it could show, expose a different side to her character, give people a different or better sense of who she was as a person.

HATCHET: There’s moments in the book where it’s just so poignant.

MARTINS: Well, it’s a very touching story. I think against incredible odds, she tried to live the semblance of a normal life. And that wasn’t an easy thing to do. Especially faced with what she had been accused of.

HATCHET: Do you have a better sense of why she stayed? Instead of moving away and maybe becoming a cause célèbre in France, where it didn’t matter what you did to be accepted into society.

MARTINS: Well, it was certainly stated after her death that she stayed at the advice of friends because they told her that although her first instinct was to leave Fall River that it would appear as if she were running away. But that she later came to regret that decision and I think that is true.

BINETTE: I think when you look at her life the last thing she would have wanted was to be a cause célèbre. Because the degree of normalcy that she found in her life, I think, really comes to light in a lot of the research that we’ve done with people and characters that have been brought to the forefront who were very important to her. People that she cared about very much that were ordinary, honest, hardworking people. Which is totally at odds with what the stereotyped Lizzie Borden of myth has been assumed to have been associated with, or even been accepting into her life, because of social class or anything else. That whole Lizzie Borden is nonexistent.

HATCHET: It’s fictional isn’t it?

MARTINS: Of course, she did have friends of her own social class that were very close to her.

HATCHET: Yes, but they weren’t the party type anyway. They weren’t the social class that mainly had these big events that you detail with other richer folks had in the city. Lavish, sort of crazy lavish things that were going on in the city—the ostentatious stuff. She was not ostentatious.

MARTINS: Not in the least.

HATCHET: And Maplecroft is quite a modest home.

MARTINS: It is a very modest home. It’s a well-appointed home, but it’s no more than that. Maplecroft is certainly not the grand residence it has been made out to be. It is a very nice house, in a neighborhood surrounded by very nice houses.

HATCHET: And it’s at the edge of that neighborhood anyway. It’s at the sort of outer edge of . . .

MARTINS: In that period things were changing and people were moving out to the Avenue. So it was a very fashionable . . .

HATCHET: It was fashionable, yes.

MARTINS: . . . when she moved there. Earlier, in the 1860s and 70s, Rock Street would have been Fall River’s Fifth Avenue, and it was its most prestigious address, but by the time they bought Maplecroft, by 1893-94, Highland Avenue was becoming very fashionable. But it was not a particularly grand home, it was well appointed but it was no more than that. And there was nothing ostentatious about it. It was just a nice house.

HATCHET: The interior of Maplecroft is explored a bit in the book, and we won’t go into that, but I do like being given a glimpse of her world inside.

MARTINS: I think it is important that people have some sense of what the house was like because so much has been made up about it. I mean, so many people who have never seen the house have written about it.

HATCHET: Same thing with 92. I mean, still.

MARTINS: Exactly. Exactly.

HATCHET: Even though you can get in.

MARTINS: But with French Street it was so easy to assume what it must be like never having seen it. And now we know what it was like. It was a nice house, but it was nothing particularly great.

HATCHET: Right, right. The Acknowledgements in this book are massive. Tons of people assisted you. Did you take notes on all those names on every piece and then go search those people out and stick them in to keep track?

MARTINS: We just kept track of it. And there were some people who didn’t want to be acknowledged. There were a number of people who were very significant sources of material who did not want their names mentioned at all.

HATCHET: Just because they didn’t particularly want people to track them down and ask them questions?

MARTINS: Exactly. You know, I think it’s very important to realize that over 80 years after her death there are still a group of people protecting Lizzie Borden. They never knew her. I mean most of these people never knew her.

HATCHET: Another generation. Third generation.

MARTINS: Right. But because of the love and respect that has descended through their family because of the family stories, they still maintain this, this sense of respect for a woman that they never knew. What I think is so interesting about that is a number of these people have significant items that would be of value but they’ve chosen not to . . .

HATCHET: Profit . . .

MARTINS: Profit, not at all. And it says a lot about her.

HATCHET: That’s funny. That is one of the things that struck me, I guess because I am not related to the case but only interested in it. If I had something like a letter or a photograph or a memento or an object that belonged, I would not sell it, but I would sort of be delighted by it and show it to people, and that is just not what happened.

MARTINS: It’s just the opposite.

BINETTE: It’s important to realize that some of the people that we were in touch with that had materials pertaining to Lizzie or had stories carried down from their ancestors, it’s not an interesting, intriguing murder case to them. Put it in your own world. Think of somebody that your mother or your father cared very, very much about, that maybe you knew as a very young child, or maybe you didn’t, all you had heard about was this wonderful relative, this great uncle in the family who was just the sweetest man and that would do anything for anybody. And then he had a very sad life and he died and had some people who were very close to him. That’s Lizzie to these people. It’s got nothing to do with the murder. It has to do with them keeping the dignity of that woman’s life in spite of all of the people around that are saying, “Gee, isn’t Lizzie Borden cool? Don’t you wonder who did it?”

MARTINS: And, in fact, because of that, they have to protect her that much more. And I think, in many cases, or in most cases, they don’t like the way the story’s been handled, they don’t like the way Lizzie’s been portrayed.

HATCHET: I don’t either. I never did.

MARTINS: They know a different person.

HATCHET: There were cases, though, where you started asking questions or inquiring about relationships and didn’t you find that, in some cases, the people didn’t even know they had what they had?

MARTINS: Oh, that was interesting. There were some people we contacted, and they said, “You know, let me talk to my sister. Let me talk to someone in the family.” And then they called back and they’d say, “You know, it’s funny. We have this and that. And I never heard that story but my sister did and maybe you should talk to her.” And then they would go through boxes and they would call and say, “You know, we have some things.” So it was interesting. And then there were other cases when we tracked people down who we knew from some little shred of information that we had uncovered, that these people were likely somehow connected, and contacted them and they said, “Oh, yes, we’ve been waiting for you to call.”

BINETTE: Those are the creepy ones.

MARTINS: And it was interesting. And in some cases, or in a couple of cases, one photograph actually, that we have, it was sent to us along with a collection of family photographs because we wanted some photographs of this family for the book.

HATCHET: Did they know who . . .

MARTINS: No. They knew who their relatives were, but they sent a box of photographs, and in that box of photographs was a photograph of Lizzie Borden.

HATCHET: So did you like drop your teeth?

MARTINS: And the interesting thing about that was it was not inscribed in her hand, but initialed. Through another family, we found another copy of the exact same photo. So it had been sent by Lizzie to two different individuals.

BINETTE: That didn’t know each other.

MARTINS: That didn’t know each other. So here these two new photographs show up, but rather the same photograph that just showed up twice, and there was no question what this was and both of them were inscribed in the same manner.

HATCHET: Wow.

MARTINS: And then there’s one instance, and this had to do with Nance O’Neil, where we went up to look at a collection of items, and one of them had to do with Nance O’Neil. The person who had it had no idea.

HATCHET: That’s probably why stuff disappears so much, because people don’t know what they have. Things get thrown away, or sold, and auctioned off as one piece, and travels around the country, until someone who knows what they are looking at spies it and says, “Oh!”

BINETTE: Like the response, “Oh, isn’t that interesting?”

MARTINS: Exactly! You know it’s like no big deal to them. But it was a very important link in the chain. If Nance O’Neil and Lizzie Borden’s relationship was a chain, this was that great big link in the middle, you know? It was just a very important link. Which is kind of cool.

HATCHET: And it was happenstance.

MARTINS: And then there were little things that we found out. Like for example, the little Maplecroft, the little B Maplecroft green label that everyone is referring to . . .

BINETTE: That’s the Maplecroft, there was no B on that one. That’s just the Maplecroft one.

MARTINS: That everyone is referring to as her little book sticker, her bookplate. Oh, yeah, she did stick it in a lot of books, but it was not its intended use, by any means. That’s not what she bought them for, that’s not what she usually used them for. So it’s just little bits of information like that that was interesting to hear. So when you see what they were intended for it makes so much more sense. You know?

BINETTE: She did have a thing for stickers.

MARTINS: She did. We know that.

HATCHET: (laughter) Do you think there were Easter Seals back then?

MARTINS: We haven’t found any Easter Seals yet. They had them. It was just some interesting personal sort of glimpses that . . .

HATCHET: Did you ever find out if she voted?

BINETTE: Mm, hum.

MARTINS: She was registered.

HATCHET: Republican or Democrat?

BINETTE: The Fall River polls do not list your affiliated party, so . . .

HATCHET: Shoot!

BINETTE: We know the people that she knew voted Democrat, but that’s not telling you anything.

MARTINS: At least some of them did.

HATCHET: So we still don’t know whether she was a Republican or a Democrat.

MARTINS: No, no. We may find that out eventually.

HATCHET: Or an Independent, if they had those back then. Or a Whig.

MARTINS: Certainly when we started this, I don’t think either one of us expected to uncover as much as we did. And in a couple of cases, when the floodgates opened, and they literally did . . . I remember one instance, where we were at someone’s house, who we had gone to see, and they just kept bringing these things out.

HATCHET: (laughter) Well, it’s like they were probably testing you with the interview too, right? A little bit?

BINETTE: There was some of that.

MARTINS: There was some of that. And then there was also, there were a couple of people who had material, and they knew they had material, but they didn’t know if it would be significant. And then, when we told them what it was like, they said “Oh, oh.” So that was interesting. And we do know much more about her life now. I mean we have a pretty good sense about how she spent her days. And we know where she traveled. And we certainly know who her friends were. We know every coachman and chauffeur that the Borden sisters had from the time they moved to Maplecroft until Lizzie’s death. There was a whole string of them and we know them all. So it’s information like that, material like that, that’s just interesting. And some of them she only had for a couple of years.

BINETTE: And even with the ones she only had for a couple years, it is interesting how she managed to establish relationships with them.

MARTINS: Lasting relationships.

BINETTE: With the families.

HATCHET: Well, the stories that are told of the people, sort of before, during, and after their relationship with her, as a servant or as a coachman, those are great stories. I mean those are stories that have never been told before, in any way, shape, or form.

BINETTE: Right.

HATCHET: And they’re once again little tidbits of . . .

MARTINS: Little anecdotes.

HATCHET: Little anecdotes. But some of them are longer than that.

MARTINS: They certainly are.

HATCHET: And the sort of tragedies and real life experiences of those people too, which will probably become a little more well known because of the book.

MARTINS: Oh, I think there’s this whole group of people who she knew and had close relationships with that no one knew of. There’s this whole new world.

HATCHET: Did you start with the will and go back from there and meet people that way?

MARTINS: Not really, because that was too obvious. I don’t want to say too easy, but it was too obvious a place to start. It had already been done.

BINETTE: A lot of the key players that we discovered aren’t mentioned in the will.

MARTINS: Right. Lizzie had a number of people that she was very close to and had done a great deal for . . .

BINETTE: . . . in her lifetime.

MARTINS: . . . in her lifetime, that they didn’t need to be mentioned in her will. And then she also had a number of friends who were just passing acquaintances, or people that she had long-term friendships with who she wouldn’t necessarily mention in your will. And then, of course, you have to remember that there was a will, but there likely was also a memorandum as to where she might have wanted some things placed. And that would be something that there would be no record of. Oftentimes, when someone leaves a will they also leave for your executor or executrix you leave a list of certain pieces that you want to go to certain individuals that are not mentioned as legatees of the will, that’s not uncommon at all, that’s commonplace.

HATCHET: And it’s not filed with the court? It’s just instructions. . . Did the administratrix of her will . . .

MARTINS: I’m not saying that in Lizzie’s case we found that document. We never did find that document. But I suspect, in fact I would say, that because of where certain things ended up, that clearly are not specified in the will . . .

HATCHET: I see, I see.

MARTINS: I’ve never known a Yankee maiden lady who didn’t leave a memorandum

HATCHET: See, that’s the thing. You know the pattern.

MARTINS: You have to think . . . I’ve spent most of my life with elderly maiden Yankee ladies. And you have to think in some cases the way they might have thought. And especially someone like Lizzie who was so cautious and so careful about everything. . .

HATCHET: But coming from a place south from here, without the experience you have had with Mrs. Brigham and learning the families, I mean you know them like you can reel them off the top of your head. I mean you knew these people.

MARTINS: That’s the thing, you know, some of these people, I mean a lot of these people were new contacts, but there was a chunk of them that were people who, and some of them are dead, I mean, but they were people who . . .

HATCHET: And you talked to them?

MARTINS: Well, I talked to them, you know, thirty years ago, or I had correspondence with them thirty years ago, twenty years ago, or whatever, so I know what they said, and also knew their families, so, and then Dennis met them when he was here, so . . .

HATCHET: You once teased me with, “Imagine how so and so would think, a certain person like that would think in order to retire, and where they would retire.” And I couldn’t do it. You know, not being from around here I think had a major impact on my . . . . you know, so when I read about Lizzie I’m discovering New England life as well. I’m discovering, you know. I’ve also thought of Andrew as being less of a miser and more of a Yankee, and that not having a negative connotation.

MARTINS: I don’t think Andrew Borden was a miser at all. He was just true to that Yankee heritage.

HATCHET: But I don’t know that based on my own experience living here, I only know it based on sort of a semi-commonsensical idea about him.

MARTINS: Sure. What we tried to do with that is take other examples of Lizzie’s contemporaries and sort of explore their relationships with their fathers.

HATCHET: Right.

MARTINS: You know, to give you a sense of, you know, that Andrew Borden really wasn’t that uncommon. He was a man of his time.

BINETTE: I think it’s best illustrated in one example, one diary, where a young girl is very disgruntled because her father put a lid on her spring break and her expenditures and cutting back the tide and actually telling her that when he was her age, he had no where near as much money.

MARTINS: He said “you have more expended on you in a month than I had in a year.” Her father told her this, so it wasn’t uncommon and the Borden sisters were clearly well dressed and well fed and.

HATCHET: And the whole dressmaker thing. Everybody had dressmakers and it wasn’t as, you know . . .

MARTINS: You didn’t buy clothes off the rack.

HATCHET: Right. Today, we think of that as a luxury.

MARTINS: Right. And the Borden sisters’ dressmaker, Mrs. Cummings, was a very well known dressmaker in Fall River, she worked for some very prominent families. So it wasn’t like Mrs. Cummings was a lady who lived around the corner and made dresses. She had clientele extremely well placed in Fall River.

BINETTE: And it could very well have been that they had to run up their own dresses. I mean, Alice Russell, she ended up as supervisor of sewing. So I’m sure if they needed to know how not to drop a stitch . . .

HATCHET: Well there was a sewing machine at the house.

MARTINS: Right.

BINETTE: Right.

HATCHET: There were things that women did . . .

MARTINS: Well, Lizzie said in her testimony that Mrs. Borden had asked her to help her fit a dress and she did help her to the best of her ability.

HATCHET: Right.

MARTINS: So clearly that was going on. You know in a lot of these families, the dressmaker would make a garment, but any trimmings or if they had to be finished, oftentimes the women would do that themselves. For example, lace, you would take lace from one garment and move it onto another and things like that were often moved because lace was so valuable. But they clearly were well dressed and well fed.

HATCHET: There was a big discussion on the Lizzie Borden Society Forum recently about the pigeons.

MARTINS: Yes, which we talk about.

HATCHET: Right. And about the killing of those pigeons and what it meant. Lizzie never said that they were her pigeons, that they were pets.

MARTINS: No.

HATCHET: And Emma never said that they were pets. Just that her father had killed some pigeons.

MARTINS: Right.

HATCHET: Do you think that if they were her pets she would have said he killed my pigeons?

MARTINS: Well, we explore that, you know that. I think the answer to that is very simple. But it is another one of those things that has been so blown out of proportion . . .

HATCHET: Right.

MARTINS: . . . and people have read so much into something where it just simply doesn’t exist. And I think that her testimony makes her relationship to those birds very clear.

HATCHET: I thought so too.

MARTINS: And it’s right there, it’s not even . . .

HATCHET: It’s a nothing, common . . .

MARTINS: It’s not even a point worth discussing because it . . .

HATCHET: It happened.

MARTINS: But it was nothing uncommon. I don’t know where the story came from that Lizzie Borden kept pigeons. We discuss it, and we write about it, but . . .

HATCHET: Well somebody like Victoria Lincoln took it and ran with it.

MARTINS: And people believe it.

HATCHET: And made it some kind of psychologically damaging moment for her. And then claimed they were her pets.

MARTINS: Because she needed an explanation.

HATCHET: People did have pigeons and pigeon clubs and coops and things.

MARTINS: Of course.

HATCHET: But there was no sense that there were coops in that yard or in that barn that one would keep pigeons in.

BINETTE: They also ate squab.

HATCHET: Right. Which is little pigeons, right?

BINETTE: Uh hum.

MARTINS: Well, we clearly discuss that and squab comes up. It’s pretty easy to guess what those pigeons were intended for.

HATCHET: How long do you think it will take before it unblemishes her record? There’s so much in the book that proves beyond a reasonable doubt that certain myths surrounding her are baloney.

MARTINS: Right.

HATCHET: Will it hopefully help people to stop repeating that malarkey?

MARTINS: No, I don’t think it will at all. I think that it will make her life perhaps a little clearer and that’s all documented, but people are going to continue to believe what they believe regardless. And I don’t think that a lot of people have any intention of changing their opinions.

HATCHET: That’s so funny, because just today, President Obama released his certificate of live birth. He told Hawaii to go ahead and release it. And it’s online, and they’re still saying it’s a fake, it’s a Photoshop, it’s a forgery, it took him too long to . . . people who wanna think the way they wanna think will think that way no matter what evidence is presented.

MARTINS: Exactly.

HATCHET: That’s so crazy.

MARTINS: If anything else, I just hope that it gives people some thought and presents a much clearer picture as to what her life was like. And there were certain things that were relatively easy to dispel. I mean there’s so much myth that clearly is based on erroneous information.

HATCHET: How long do you think it took you to do the book from today backwards in time to when you started? How long was that process?

MARTINS: Well, for us, it was nine years, but . . .

HATCHET: The writing of it.

MARTINS: Right. But, of course we couldn’t sit down and just write and do research, I mean, there was an Historical Society to run. So there were other things that had to be done, so it wasn’t like there was continuous uninterrupted time to work. But in some ways I think the process began years ago. Years ago. Some of it was just based on very personal relationships we had, I had, with people.

BINETTE: And a lot of the newer relationships didn’t happen over night.

MARTINS: No, they took a long time to cultivate.

BINETTE: It took years to cultivate and gain the trust of people who were very . . .

HATCHET: Private.

BINETTE: Private but in light of . . . going way back, people who had stories about one of their ancestors chasing Edward Radin out of their house with a broom because he was asking questions that were, according to them, none of his business. So, I mean, we were going out to some people and this is their past experience with people writing a book on Lizzie Borden.

HATCHET: Right. Paparazzi type people.

MARTINS: Well, you don’t call someone out of the blue. I mean if someone calls you, and you don’t know who they are . . .

HATCHET: Well in New England you are introduced to people through people.

MARTINS: Exactly. And that’s how we did it.

HATCHET: I noticed that. That’s a very New England thing.

MARTINS: That’s pretty much how it was done. I mean, there were a number of cases where it would have been simple enough to pick up the phone and call someone, but we couldn’t do that.

HATCHET: Right.

MARTINS: Just because you don’t do that.

HATCHET: Well, I’ve noticed that myself just recently.

MARTINS: There are certain ways that you go about things and sometimes they take time. You have to be willing to wait.

HATCHET: Plus, not everyone that you’re contacting is online and easy to reach, so letters have to be sent and telephone calls . . .

MARTINS: And sometimes letters have to be sent through people who know people who might know that person. So it’s not, it doesn’t happen overnight.

HATCHET: I found that the book speaks with one voice, and yet there were two authors. I don’t know how you guys accomplished that because you are quite different people.

BINETTE: Neither do we.

MARTINS: At this point, reading things, literally, I mean in a lot of cases it was “Oh did you write that or did I?” But we wanted the book to sound sort of period.

HATCHET: It does. Language wise, it has the vocabulary of period.

MARTINS: In order to sort of invoke that whole feel for the period, we want it to sound period.

HATCHET: But you can’t differentiate between the two voices when you write.

BINETTE: I guess that’s a good thing.

HATCHET: It’s a great thing! But its a remarkable thing. I think it’s harder to accomplish and lucky that you did because otherwise it would have been a very choppy read, to have a sense that oh Michael wrote this chapter and Dennis wrote this chapter, when it’s Michael wrote this sentence and Dennis wrote that sentence.

MARTINS: Yeah, it’s all sort of . . .

HATCHET: Did you like take sections and write it and pass it along to the other person and then they edited it and edited it?

MARTINS: Well sure. Anything that I wrote he looked at and made changes to it, and anything that he wrote I looked at and made changes to, so yeah, it just kind of went back and forth. But, it just sort of evolved that way.

BINETTE: In some cases it was “Oh, I can’t stand this any more . . . here.”

(laughter)

MARTINS: There were a couple of instances, I know with one family in particular I said, “I just can’t stand these people any more, Dennis, it’s yours. I just can’t deal with it any more,” you know. Because you just get so involved in these people. But it works. It is a lot of book. It’s not for the faint of heart.

HATCHET: It’s a lot of book . . .

MARTINS: It is a lot of book . . .

HATCHET: Well, it rivals Stephen King (laughter).

MARTINS: Well, you know, there are a lot of photographs.

HATCHET: You can’t lay it on your chest when you’re lying in bed and read it, unfortunately.

MARTINS: Unless you have a large chest, you could.

HATCHET: You’d have this imprint forever.

MARTINS: It is a lot of book, and . . .

HATCHET: Will certain people that I know that live in New York—Bob—be able to carry it on the subway and read it like you . . .

MARTINS: No. I don’t think you’d want to be doing that. But there are a lot of illustrations, all of the photographs have been restored, if that was necessary. And the illustrations are throughout the text, so when you’re reading about a certain person or certain incident, it’s just kind of nice to have that image right there.

HATCHET: Right, there’s not all the pictures in the middle.

MARTINS: And that helps to tell the story. It just kind of weaves the whole thing sort of through. It’s kind of like a . . .

HATCHET: . . . a textbook. In a way . . .

MARTINS: Well, but it’s not, it’s more like a chatty sort of romp through . . .

HATCHET: (laughter) A chatty romp! I like that.

MARTINS: . . . 19th and early 20th century Fall River, you know. You just kind of meander through, kind of like a vine.

BINETTE: It’s a tour.

HATCHET: (laughter) It’s a tour!

BINETTE: It’s a tour that’s sort of alive, really.

MARTINS: And speaking of tours, we know lots about Lizzie’s tour now.

HATCHET: (laughter)

MARTINS: That in itself is fascinating.

BINETTE: Segue right into that. It does stand as a social history of Fall River and it does stand as somewhat as the first biography of Lizzie Borden.

HATCHET: Well, it is also a biography of the city. I clued into that and loved that part of it. I mean, I couldn’t wait until the next Lizzie mention happened, but while I was getting to that point in the book, I was fascinated by the people that were being . . . and it really isn’t about a place but people within a place and how unique Fall River is. I think it helps form someone’s sort of understanding of Fall River as a city and how different it is from other communities. I think you used the word, did you use the word parochial? What was the word you used for the fashions?

MARTINS: Parochial.

HATCHET: Parochial. And sort of out of date . . .

MARTINS: Fashionably out of date.

HATCHET: Fashionably out of date, right, but not cutting edge. Certainly.

MARTINS: It wasn’t cutting edge but it was . . .

HATCHET: And cutting edge was looked down on. Which I thought was funny.

MARTINS: It was.

HATCHET: To someone who had the latest fashions.

MARTINS: It was fashionably out of date because you wouldn’t want to be branded vulgar. But of course you could still be dressed in Paris, and they were, you know, but it just had to be done the right way.

HATCHET: And you had to be careful when you went to Europe on your tours and shopped what you brought back. Right? You had to wait a year until you pulled those dresses out. (laughter)

MARTINS: Well, you could be dressed by someone, you know, like Worth, you could be dressed by Worth and come back with a dress and wear it. But if you were wearing some outlandish creation by Worth that was being worn in Paris, it was certainly going to be a bit much for Fall River. You just had to play your cards right. If you wanted to be received. And that is what it was all about. You either were received or you weren’t. And the interesting thing too is the fact that there was never a social register. Because there was no reason for one. It wasn’t needed. You knew if you were in or out. So why put it in a book?

HATCHET: So social registries are books of people. Like the red book or whatever. Boston . . .

BINETTE: Boston Blue Book.

MARTINS: The red book was for prostitutes.

HATCHET: Oh, I’m sorry. (laughter) The red bloods . . .

MARTINS: Blue book, blue book. The red book was probably a lot more fun. The blue book, they were published in Boston and there, of course, was a reason for that, but in a city like Fall River where society was so much smaller, it wasn’t necessary. You knew if you were in or out. Certainly by 1910-12, that period, in the regional blue book, there was a section for Fall River. But earlier on, it wasn’t necessary.

HATCHET: How much money did you have to have in order to be in that section?

MARTINS: It wasn’t even based on money in Fall River.

HATCHET: Oh, it wasn’t?

MARTINS: Pedigree. Pedigree had a lot more to do with it than money. Wealth certainly helped, but blood was much more important. Why couldn’t you be received here? I mean, you couldn’t buy your way into Fall River society. That wouldn’t happen.

HATCHET: But yet a lot of the people who were in that society were mill owners.

MARTINS: Oh, they certainly were wealthy and clearly, I mean, as a by-product of wealth you obviously want to become more exclusive and you want to attain your own sort of . . .

BINETTE: But I think looking at that in terms of the Lizzie Borden story, it makes perfect sense that Andrew Borden was smart enough to know that he wasn’t going to buy himself into the highest society in the city, regardless of . . .

MARTINS: I don’t think he ever really courted society, certainly it doesn’t appear to be something that interested him.

HATCHET: Well, his side of the bloodline was the worker class, the merchant class. The lesser Borden side I guess you’d say, so it wasn’t something where they could actually transcend over to the other side even though they were related. So they knew each other, and were pleasant to each other, but they were . . .

MARTINS: But there was never a stigma in Fall River about being in society and being in trade. Where in a lot of cities, very cosmopolitan areas, if you were in trade you were not received socially. You could be in trade and removed from that, but if you physically were in trade, if you maintained an establishment, then you wouldn’t be received. In Fall River it really didn’t matter.

HATCHET: Lately there’s been some writings about Lizzie’s unbelievable passionate desire to become a part of the society that she was locked out of because of her father, and I just never thought that that was one of her things she needed in her life or wanted.

MARTINS: She certainly lived the majority of her life surrounded by local society and she knew people, especially as a young girl growing up, and when she was in her early teens, she knew people who were, or came into contact with girls who were well-placed in local society.

HATCHET: But there is no evidence that she pined for that, is there?

BINETTE: No, but I think that if you embrace that theory, then you’re giving fuel to the flame. Making her discontent, and justifying her taking action against . . .

HATCHET: Exactly, exactly.

BINETTE: I’ve always said they go hand in hand. The more miserable you make her, then the more you justify . . .

MARTINS: And clearly she did not live an ostentatious life, by any means.

HATCHET: And she could afford it.

MARTINS: She could afford it. But she did not live . . .

HATCHET: She didn’t die penniless. She died with a lot of money still.

MARTINS: She still had a considerable amount of money and she certainly enjoyed her life . . .

HATCHET: As did both.

MARTINS: She loved to shop. She loved to give gifts to people, but she wanted nothing given to her in return. You couldn’t do anything for Lizzie Borden, she wanted nothing done for her, and some people could say well she was buying friends, you know if she gave then that gave her the upper hand over people. In Lizzie’s case, I don’t think that was the case at all, because these people were sincerely interested in her and she was sincerely interested in them, to the point where, when you read her letters, she knew about the day to day workings of their lives, they confided in her the very intimate details that you wouldn’t confide in them . . .

HATCHET: Well, she had relationships with them that were real.

BINETTE: There’s one thing in relation to that, there’s sort of been a desire for people to look at some of the known instances where Lizzie had befriended people that worked for her, or that she cared about people that worked for her, and kind of diminishing those relationships by saying that she could only find relationships or people that cared about her in those that were subservient to her. And I think that that’s unfair.

MARTINS: Oh, it’s very unfair.

BINETTE: It really diminishes the relationship itself, it diminishes the people that are involved in those relationships, because she apparently didn’t care. Social hierarchy was not important, what was important to her were people that could be loyal, that people were discrete, and valued her privacy, and actually apparently valued their own privacy, and were honest with her and up front and it didn’t matter if they were people that worked for her or people who knew people who worked for her, or people of her own class.

MARTINS: And they are the same who are maintaining that privacy to this day. Which says a lot. It says a lot.

HATCHET: Sure does.

MARTINS: And that’s one of the most intriguing things.

HATCHET: Well, she sort of crosses party lines that way, she has money, she can come and go as she pleases, in a way, and live the life that she wants to live, but she doesn’t go crazy with it. She is very conservative in her life, I think.

MARTINS: She clearly enjoyed fine things. She surrounded herself with very nice things.

HATCHET: But not the absolute most expensive things.

MARTINS: No, no. She bought her silver and her jewelry from the finest establishments. And she was well dressed. And she bought her books from the best shops. And I am sure her furnishings came from the best shops in Boston. When she gave gifts to people, she didn’t buy something where you might say, “Well, instead of going to Tilden’s or instead of going to Tiffany and Company, I’ll buy that at McWhirr’s because of their station.” What she bought for herself is what she gave people. So she was clearly gifting things at the same level as she was buying for herself.

BINETTE: And not for them to say, “Oh my gosh, she went to, you know . . .”

HATCHET: Right. Well, I’ve met people who give gifts and don’t want any in return. And I have found them to be people who, in my experience, they sort of enjoy the giving so much, and the satisfaction of presenting something to someone that is important to them. They don’t just give, they give something nice.

MARTINS: And she also said that she had money to buy what she needed. So there was no reason for anyone to give her anything.

HATCHET: But the not needing anything in return has to do with there’s nothing I need, first of all, and second of all, you couldn’t give me what I really need anyway.

MARTINS: This I think, in a lot of cases, was her way of saying thank you. She appreciated the friends that she had. But I believe, certainly, especially later in her life that she was wise enough and was surrounded by enough good friends that the insincere would not have been admitted into that circle. Because she had enough very close friends who, I think, would have realized what was going on.

BINETTE: I think in some cases, correct me if I am wrong, there are going to be some people who actually do not like the Lizzie Borden that we found.

HATCHET: Why? Because that won’t fit into their world view?

BINETTE: No, I think that some people sort of rejoice in the fact that Lizzie can be this moody person that could have flown off the handle and was kind of off. For the rest of her life.

MARTINS: She certainly doesn’t appear to be off at all. Melancholy, yes. Prone to periods of depression, yes. Understandable. Lonely, even though she had people around her, I think at times yes she was. But she certainly wasn’t the recluse of legend. She wasn’t that scary lady in that house on French Street.

HATCHET: Who locked herself up and didn’t want to be seen.

MARTINS: The remembrances of so many people who remember when they were kids that she was always dressed in black and really scary. Clearly we know she wasn’t always dressed in black. In fact, I have yet to find a photograph of her later in her life where she’s wearing black. So I don’t know where that came from, except it just plays into that whole scary, sort of spooky, image.

HATCHET: To me, the big bad tragedy of this is that she has become an icon for Halloween axe murderers. I mean, she is still being used to this day as this scary, crazy woman who kills people.

MARTINS: Of course, and that’s going to be the case, I think, forever. And even at the time, at the time there were children in the neighborhood who, you know, said that when throwing eggs at the house on Halloween that they envisioned an axe coming out of every window, because this is what they were brought up to believe. They didn’t know her.

BINETTE: I think, unfortunately, I guess, the Elizabeth Montgomery movie’s kind of been the big proponent toward that whole image for a generation

HATCHET: Well, it’s the visualization of her doing it.

MARTINS: Exactly, exactly.

HATCHET: And that’s what they see in their head.

BINETTE: And they see her holding a hatchet in her hand and that’s become fact.

HATCHET: Because it is in everyone’s memory.

BINETTE: And it’s amazing.

HATCHET: And it was on TV, not at the movies.

MARTINS: You know what’s so interesting? One family in particular, the descendants didn’t realize, and clearly Lizzie Borden the name is know all across the world, I mean, certainly all across America, and this particular gentleman had no idea that the Lizzie Borden that his ancestors were so friendly with was Lizzie Borden the accused axe murderess. He assumed she was of the Borden dairy family, because she was such a lovely person that she couldn’t possibly have been associated with this axe murder. So in his mind, he never made the connection. And this is a man who is, what, in his 70s, late 70s? And he never made that connection to Lizzie Borden.

BINETTE: He’s also one of the people that . . . we got the same stories from a variety of sources, which is interesting. People who didn’t know each other. And one of the first times Michael had spoken with this man, and I spoke with him shortly after, and we were having a conversation, and he started to tell me things that were the answers to the questions that I hadn’t asked him yet. And, another creepy moment. I realized that all of these people had been brought up with the same stories, and in his case it was not even that Lizzie Borden, it was just a woman named Lizzie Borden, that they had all been brought up with the same stories about this person that the previous generation in their family had known intimately, and called friend. And they were the same stories coming from this state and that coast or this state and that coast or that country.

MARTINS: Right, and we had it in Asia, we had it in Europe, we had it in Canada, we had it in, you know, the same stories as they related to that particular individual’s family. So you know that these people aren’t making this up. And then they had the documents to prove it, you know.

BINETTE: There was a summer a few years ago. It was uncanny.

MARTINS: Two weeks.

BINETTE: Two weeks straight.

MARTINS: Every day.

BINETTE: Every day. There wasn’t a day that went by where the phone didn’t ring and it was a new lead, we opened the mail and it was an “Oh my God,” or “We’re sending you something.” And the thing that I think has been really rewarding about all this whole project is that so many people jumped on the bandwagon. And they were thanking us for allowing them to be a part of this project, when we were saying, “Are you kidding? You’ve given us priceless information” and . . .

MARTINS: . . . and they didn’t see it that way. One woman, when I called her and spoke with her the first time, she said, “I was wondering when the Historical Society was going to do something about this.” She was waiting for a phone call, you know. But it never would have occurred to her to contact the Historical Society.

HATCHET: I understand. Based on what you are telling me about the people that you met, it makes sense now why they wouldn’t call you. You know what I mean?

MARTINS: Right, right. That’s just not the way it works.

HATCHET: Plus, a lot of them didn’t know it was that person. They had to put two and two together as well. Or, in some cases, they hadn’t looked at their own stuff. Their family’s photo albums in a long time.

MARTINS: Several people said that this was going to give them a good reason to go through some things. And then when they went through some things, or when we went to their homes and went through some things, it was like, oh, wow!

BINETTE: There’s one man in particular, a great, great guy. But it’s funny because I received an email and he was in the process of doing some research on his own, and I received an email saying that he thought there was a connection between his, grandfather?

MARTINS: Grandfather.

BINETTE: Grandfather and Lizzie Borden. And I put it in the back pocket, unfortunately, that day and within two days my whole system crashed. I lost everything. Including the email from this man. And two years went by, three years went by, something like that, and the name came up.

MARTINS: The grandfather’s name came up.

BINETTE: And it’s like, wait a minute. Oh, that’s the guy.

HATCHET: Wow!

MARTINS: And then you had to go find him.

BINETTE: I made this phone call and this woman answered the telephone and she said, “Oh, hi!” She said, “You wanna talk to my husband!.” I guess so. So she passed me on. And as it turns out this man was the man who had sent me the email, years ago, and just started talking, and this man was filled with wonderful, terrific, terrific stories, came down to visit, and we spent some great time with him and his brother, and we’ve been back and forth over the phone, but these wonderful relationships that develop with these people that . . .

MARTINS: And it’s been going on for years now.

BINETTE: Yeah. And they just , like, so much enjoy being able to give you the information, and just getting access to this stuff. It’s just wonderful. It’s a win-win for a lot of people.

MARTINS: And certainly we weren’t always successful. There are some individuals who have material that have decided that the time is not right for them to make their material public.

HATCHET: Do you think that once the book comes out they will say, “Oh, the time is right. Now it’s time!”

MARTINS: I don’t know. I can respect them for that. I can understand where they are coming from. And I don’t blame them for that. I think it makes sense. I think they’re being very wise.

BINETTE: Because there are some people who are actually sacrificing their privacy just to be included and have their stories . . .

MARTINS: Right, because there is some very personal information there, some very poignant information there. And then there is some material that we were given access to, that we’ve been able to look at, that we have not used, because we know the families are not ready to have that material made public, for personal reasons. There is still this one very significant collection of letters out there that cover a lengthy period. Funny story about letters, I was in touch with a woman who we tracked down, and called her, and met with her, and in the course of speaking to her she said, “Oh, yes, I have a few letters that might be of interest to you and I’ll come down and chat.” And so we talked back and forth about a few things and then she came to the Historical Society and, in that instance, she arrived with a bag. We sat down and she had her letters, and the letters were very significant, I mean, very important letters, and a large collection of them, and then she took this plastic bag with all of this stuff in it, and she sort of threw it at me and said, “Oh I have this too. I don’t know if this will be of any interest to you. It’s just notes and cards.” Forty-seven of them! And that documented about twenty years? A twenty year relationship?

BINETTE: Actually, that bag was a whole unexplored avenue.

MARTINS: Because it led in so many different directions. And then we went off because of that bag and met with a couple of families, one of which . . . it was really funny, because we had to go from Fall River, and then we contacted some people in New Jersey, who had cousins who were in Connecticut who had cousins in Massachusetts, who knew somebody else in Connecticut, who knew people who might have some information. And following all those leads . . .

HATCHET: Did any of it ever lead back to Fall River? That would have been funny.

MARTINS: No. But a lot of those leads led right out of the country. This particular one led right out of the country. But anyway, that brought us to a very significant collection of material as well. And in some cases, all you have to go by is a first name. But when you know who the people are, and who the people knew, you can find out who that first name belonged to. When you get the surname, then you can run with it. So there’s sort of a lot of detective work there.

BINETTE: Well, I still think we need a storefront with venetian blinds, fedoras, and cigars.

MARTINS: Yeah, a detective bureau.

(laughter)

HATCHET: The Fall River Historical Detective Agency.

BINETTE: The rewarding part, or one of the rewarding parts, is the phone calls where you asked someone if they’re so and so, who’s related to so and so, and you get that, “Yes . . . “

MARTINS: That’s why you call and leave your number to call back.

BINETTE: And then you start to explain what’s what, and . . .

HATCHET: It’s sort of like getting that call that they’re doing right now where they’re tracking down all the royal relatives, and they’re knocking on people’s doors and saying you’re four thousandth in line for the British throne, here we can prove it, and their like, oh, ok. In other words, you’ve been looking into my genealogy and I didn’t know it.

MARTINS: And in some cases these people were delighted and wanted the material that we had uncovered because they didn’t know anything about their families. And some of them were very, very elderly. There was one gentleman who was, oh, 102, 103? And very much with it. And he could remember Lizzie when he was a little boy. Lizzie driving around, as he described it, “in her glass car.” And he had some interesting stories. And there was another woman who was in Florida, and she’s nearly 100, and she’s descended from a family that was one of the Borden’s coachmen. And she had some very interesting stories. And she was very with it.

BINETTE: And then there is one of your new best friends that used to like to ride his bicycle up the hill.

MARTINS: Yeah, yeah. There are a lot of contacts like that, where there are people that you just start maintaining correspondence with.

HATCHET: Didn’t you tell me a story about the Cook family? And how you beat yourself up because . . .

MARTINS: Oh. Yeah, that was a good story. Charles Cook’s niece, who I knew for years, and had been to her home, and I knew, I mean, that she had things that belonged to Lizzie, and, you know, it never occurred to me at the time to ask where she got them because so many people had things and you don’t ask someone where their possessions came from. And it wasn’t until we started doing research for this book that I made the connection and saw the name, and . . .

BINETTE: I remember that day.

MARTINS: I couldn’t believe it.

HATCHET: And she’s gone now, right?

MARTINS: Oh, she’s long gone. And all of her things have been dispersed, and there’s no family, she was unmarried, and so the stuff is floating around out there somewhere. But she had furniture, and carpets, and I had tea from her silver set, I mean she had all of this stuff, and it made sense, it made absolute sense, and I thought wow, why didn’t I ever think of asking her? And you know, with somebody like Russell Lake, I knew Russell Lake for years, and he was a great old guy, and there are a lot of things that I think, oh, I should have asked him about that.

HATCHET: Yeah, I told you what you should have asked him.

BINETTE: (laughter)

HATCHET: I wanted to know what she sounded like.

MARTINS: I’ve got a bunch of Russell Lake letters and I should go through some of that stuff and see, because he would write little things, and you know. . . .

HATCHET: I want an 8mm of her walking down the street. Waddling away.

MARTINS: Well, maybe it exists, who knows . . .

BINETTE: The thing that I think is really fortunate is I go back almost twenty years, but Michael goes back thirty. And it’s that ten year period there, a lot of people that he spoke to were people that had memories of a generation that’s passed since. And he’s kind of brought those anecdotes and those memories to this book in a big way. And I think that’s key, because those reminiscences are woven at the heart of that period. And I think it’s an important part.

HATCHET: What do you think Lizzie would think after all this time that there is this big, big, big book with her picture on the cover, and it’s like published by, you know, two streets over.

MARTINS: I think that if you look at the body of work that has been published, where so much of it does not paint a good picture of Lizzie, I’d like to think that she’d be somewhat pleased that we were telling the other side of the story. But then there are also some very personal details, I think, that were never intended to be published. But I think there is a reason for publishing them. And I’ll tell you, I’ll be perfectly honest, in some cases, there were things that we had access to that we didn’t use because they were too personal. Maybe, eventually, the time will be right for that, but there’s still a significant amount of material maintained in private collections that, you couldn’t possibly use all of it. I mean, (laughter) have you seen how thick this thing is? Can you imagine, it would be like the encyclopedia of . .

BINETTE: It would be like a fence post. No, I think that she might think that we gave her a chance in this book. That we didn’t cut and dry say this is what we think happened, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. We didn’t go there. It’s not about that. It’s about her. And we’re giving her some breathing room.

HATCHET: Do you think Fall River could finally accept her as a daughter of the city, instead of, sort of, I don’t know, mocking her or assuming the worse therefore it is a forbidden topic. Or they don’t want the city to be known for her?

BINETTE: No, I think that’s putting too much thought on the city’s part.

(laughter)

HATCHET: Well, will she become respectable to talk about?

BINETTE: I don’t think that they think of her even that way.

MARTINS: You know, there was a group of people, a generation past, and certainly there are still a few who looked as this sort of a scar on Fall River and it wasn’t discussed . . .

HATCHET: Right.

MARTINS: . . . and that’s still the case, I think, with quite a few people. The people who knew her, or the descendants of the people who knew her, certainly don’t like the way it’s been discussed. But the times have changed. But, unfortunately, I think what has happened is Lizzie’s life has been so overshadowed by myth, so . . .

HATCHET: But other cities have the Hawthorne House and they have Emily Dickinson’s house, and she’s got her peccadilloes and secrets and . . .

MARTINS: She’s certainly a woman with big issues.

HATCHET: . . . and big issues and more famous than Lizzie Borden, absolutely, but there is a sense of ownership about these people that the communities have where they’re sort of proud of them as complex individuals.

MARTINS: But the difference here is that you are talking about a brutal, horrific murder. You know, and I think because of that, how do you present the Borden murders in a tasteful manner? It’s such a distasteful subject. So it’s a difficult thing to do.

HATCHET: Well, you did it by talking about the history around her and through her, and that’s my point. My point is that you can come to appreciate the city and its stories just by becoming interested in her. That that leads to bigger and bigger and bigger things. So she’s not just this sort of icon of murder, or some event that happened in 1892, but that she’s a product of the city in lots of very interesting ways. And to know the city of Fall River . . . you have to know the city of Fall River to know Lizzie Borden, and vice versa.

MARTINS: That was really the intent of this book.

HATCHET: Right. And that makes me want the city to sort of open their arms a little bit, because they are her and she is them and. . .

BINETTE: Well, she is a daughter of Fall River and she lived her entire life here.

HATCHET: Yeah, and that’s not something to be embarrassed about or ashamed of or guarded about.

MARTINS: Again, if anything else, there’s the whole other side of the story and if you focus on some of that, which is all documented, that’s where the fact is. I mean, no one knows who murdered the Bordens and no one is ever going to know. But we do know how she lived her life after August 4, 1892. So if you kind of focus on that, maybe it makes it less interesting for some people, but I think it might make it more intriguing for others. And you know we tried to make it a point of not looking at her life through sort of rose-colored glasses. But, we were very hard pressed to find any documentation for any of these outlandish stories.

BINETTE: Or disparaging remarks.

MARTINS: Exactly. Very few disparaging remarks. Now certainly, she was not a woman that you wanted to cross. Lizzie was very careful about how she lived her life. She only let a few people in. And if you betrayed that trust, then she had the ability to cut you off completely.

HATCHET: Yeah, there were a couple of stories about that. I liked those stories.

MARTINS: And she did. But you can understand why she had to do that.

HATCHET: But also to me I saw that as a strength in her. How could I do that myself? And she has to do what she had to do. And she did it not easily, but decisively.

MARTINS: She had to, to protect herself.

HATCHET: Right. But it wasn’t just to protect herself. It was to distance herself from someone else’s shenanigans. It had nothing to do with her wanting something for herself. It was just what one should have done, is distance oneself from certain people.

MARTINS: And she tried, inasmuch as people were talking about her . . .

HATCHET: But that’s a strength, I think.

MARTINS: Oh, it is. Inasmuch as she knew people were talking about her, she didn’t want people to talk. She was very cautious and careful that everything was done by the book, so that she couldn’t be criticized for some of the things that might have gone on.

HATCHET: So who’s got the diary?

MARTINS: Which diary?

HATCHET: (laughter) Lizzie’s diary. Do you think she might have kept a diary? With all of her . . .

MARTINS: We know now, based on some of the things that we looked at, that Lizzie was a very sentimental person. There’s no question about that.

HATCHET: Sentimental people often record their daily thoughts.

MARTINS: Did she keep a diary? I don’t know.

HATCHET: Could it have been ordered destroyed in this piece of paper that you’re talking about?

MARTINS: Case in point. There’s a collection of diaries in the Historical Society’s collection and there was a memorandum left by the woman who wrote the diaries. And the memorandum clearly stated that her diaries are to be destroyed after her death, but only after her family reads them, if they choose. So some of her children and grandchildren looked at them, and then all of the pages were cut from the bindings, and they were burned. And the family, several members of the family said to me, “I’m so sorry that we destroyed grandmother’s diaries.” And then, lo and behold, a few years back, a great-granddaughter in Boston called and said, “I have a box of diaries and this is who they belong to and would you be interested in having them. And when those diaries came in, they’re all random years, they’re not in any order, this woman kept diaries from the 1860s until her death in 1929, all of these pages had been cut from the diaries. Now she could never understand why she had them. But I know exactly what happened. Things must have been packed up to go to this family in Boston, and this box of diaries, there probably were boxes of diaries where the pages were being cut out because they were going to be destroyed, and this box must have been mixed up with the boxes that were sent to Boston. That is the only reason they survived. And tremendous diaries. So did Lizzie keep a diary?

HATCHET: It was done back then. Women did. Businessmen kept diaries.

MARTINS: In some ways, and this is going to sound strange, but in some ways I’d like to think that if she did keep a diary, that her trustees burned it. And I know that might not make a whole lot of sense, but I think that in some ways that could be a good thing. Would I like to see it? Of course I’d like to see it. Who wouldn’t? But I’d also like to think that they systematically did what they needed to do to protect her. And I think she deserved that.

BINETTE: Because they were diaries, they would be treated with different protocol.

HATCHET: Sure. Like underwear.

MARTINS: But a scrapbook? Now . . .

BINETTE: That is where I was headed.

HATCHET: Because that is where you lay them out and people look at them. So it’s different.

BINETTE: But there’s even one particular thing that we’ve been given access to that we deal with in the book that is very personal as far as giving you insight into Lizzie’s character and her spirituality, really, that survived. It wasn’t a diary. That’s what I mean about the different protocol. But it’s still a look.

MARTINS: And I suspect that she may have kept scrapbooks, based on other things that we know she kept. It would make sense if she had kept scrapbooks. But whether or not they survived . . .

HATCHET: I find that people who read books and collect books and have libraries, often have ephemera, they often have paper things, and save things and are collectors in other ways.

MARTINS: And she was well traveled. She traveled a lot. She would oftentimes refer to it as “running away.” She would say that she needed to run away. And she would go off somewhere. And would stay for, you know, sometimes months. And she purchased items in different cities, the cities that she visited, so through these items you can sort of track where she was going.

BINETTE: And items for other people as well.

MARTINS: Oh, yes. She was always sending things to people when she was away. Lizzie Borden wasn’t the kind of woman that, when she was away, she went shopping and bought stuff for people and then, when she came home, gave it to them. She’d send it to them. She sent it to them from wherever she was staying. She’d send them notes. If she saw something that someone would particularly like, then she would . . . you know, I don’t see her as buying it and saving it until their birthday. Or buying it and saving it until Christmas. If she saw something that she thought someone was really going to like, she bought it and she sent it to them.

BINETTE: And also not giving it to them face to face fits totally in with her character, because she wouldn’t be there so they would feel like they’d have to say, “Oh, thank you so much.”

MARTINS: She didn’t want a lot of thanks. She didn’t want to be thanked for Christmas gifts.

HATCHET: I wish that I was the recipient of some of her largesse. It would have been so cool to have the delivery man say, “Here, a package for you!”

MARTINS: You know a lot of women, especially at that period . . . I was always told, and when I say I was always told it was by the little old ladies at the Historical Society, and I was just a kid, but, to this day, if someone gives me something, a note has to go out the same day I get it. It drives me crazy if it doesn’t. That’s just how you do it.

HATCHET: I need someone like you working for me.

MARTINS: In Lizzie’s case, if you sent her a note thanking her, she would send you back a note saying why did you thank me? You know, there is no reason to thank me, so why did you thank me? So that part of it is interesting, because she didn’t need to do that.

HATCHET: Yes, but people like to do that also just to say that I’ve received it, too. Like, it’s arrived at its destination that you intended. So part of that is just an acknowledgement of receipt.

MARTINS: She didn’t even want that, in a lot of cases. You know, she’s saying there was no reason to thank her. So it’s just sort of an interesting insight into her life. But there’s still more. There’s a lot more to uncover. There’s still more out there. And there’s more that I know we will have access to, eventually. There’s the whole “Lizzie Borden’s love letters” thing. A large collection, which is intriguing.

BINETTE: I think that the whole format that we came up with for the book is an interesting one in that it’s not a chronological history from the start. That it weaves on different aspects of, and different themes within the history of Fall River. Kind of spins on itself.

HATCHET: And things lead from one thing to the other.

BINETTE: Yes, and Lizzie’s life is fit into that and we get the murder over with, actually, within some pages of chapter one, and that’s the end of that story until the trial, which happens eleven chapters later. But moving on theme, from that point to about chapter eleven-twelve, and then picking up Lizzie’s story and letting her carry the weight chronologically to the end, I think, works well, because Parallel Lives at the beginning is more of a story of the people of Fall River and Lizzie and intertwining that through tales of weddings, and merchants, and whatever is going on in the city, and the Parallel Lives at the end actually becomes more a story of Lizzie and her city. And how they are traveling in tandem toward her demise and the destruction of the heart of her city.

HATCHET: I find a lot of biographies or historical works rush the endings because there is very little amount of information about the end of a person’s life, even if they are sort of a significant person. So you can always tell that the book is starting to wind down when the facts get thinner and the story goes faster, and then all of a sudden they’re dead.

MARTINS: In this case, it’s just the opposite.

HATCHET: It’s the opposite. The fast stuff about her, the thinner stuff, is in the beginning, and the thicker stuff is at the end and so you end up with these amazing tales about her later life that, I think, that’s unique to a history of her as well.

MARTINS: In the past, when you looked at Lizzie’s life, although very little was known about her life up to the events of August 4, 1892, some was known, and then a whole lot was known about her life during the time of the trial, and then she is acquitted, and then you can get rid of the rest of her life in a few pages because no one really knew much about that.

HATCHET: She didn’t do anything else. She didn’t kill anybody else, I guess. (laughter)

MARTINS: Now we know considerably more about her early life. We do know more about her childhood, and we know more about her father, and about Abby, and certainly about Emma. But now her later life is pretty well rounded out. But of course, there are lots of days that we don’t know anything about. So there’s still a lot of material out there. But you have to question how much of it has survived. I think there was a lot of it that was destroyed.

HATCHET: So sad.

MARTINS: But you never know what is going to turn up. We’re waiting now on a collection of how many books?

BINETTE: Over two dozen.