by “Gramma”

First published in June/July, 2004, Volume 1, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Ruby Frances Cameron was born 19 April 1900 in New Bedford, Massachusetts to John Cameron and Margaret Jonsson. She broke the news to the world that she knew who had killed Lizzie Borden’s parents in a tiny local newspaper, The Ellsworth American, in January 1985. Not only did she know who killed them but her parents had been the ones to help him escape and shelter him until things settled down. As a nurse, Ruby had “specialed” Lizzie, who was ill after an operation, and had listened to Lizzie confirm the story from her own lips. Decades later, destiny found Ruby and “Gramma,” whose own grandmother had been a traveling companion for Lizzie, living within forty-five minutes of each other/ Because of this proximity they could now share the story in Ruby’s last months and form a friendship of kindred minds that still lasts beyond earthly bonds.

The telephone rang and my dear friend’s voice on the other end said, “Have you read the Ellsworth American?”

Now, how in the world would I have a copy of that, living at least seven miles out of a town that was at least 65 miles from Ellsworth, chasing after two young boys, and trying to keep the ends of daily life from unraveling? “No,” was my nonchalant reply, as if I had just forgotten to pick one up at the local convenience store. There was no mistaking the excitement in her voice when she said, “ I think there is a woman who knows something about Lizzie Borden and she is living in Cherryfield! There is an article in the paper claiming she knows who committed the murders.”

If you have lived with this story floating around in your life the first thing that pops into your head at words like that is, “Oh, yeah, …right, another one!” Bless the persistence of dear friends! She convinced me, however, that this was one I should really check into. I hung up the phone with all sorts of possibilities swimming around in my head. With two boys and a husband to look after, I did not call right away. I think it was at least twenty-four hours before I got up the courage. By then I had read the article and was astounded by the information in it. Could this actually be possible, here in the eastern reaches of Maine, to have a person who knew Lizzie personally? Only forty-five minutes away and a real live person to speak to about issues I hadn’t thought of in years, and then only briefly.

When I did call I heard a crisp sharp voice on the other end. “Hello” I said, tentatively, “I saw the article in the Ellsworth American. My grandmother worked for Lizzie and I grew up in Fall River. Do you think it would be possible for us to meet and talk?” “You are who?” came back at me. I patiently repeated my words and heard “Oh!” on the other end of the line. Then, “I didn’t think Nellie Miller had any descendants.” I chuckled and then said, “No, not Nellie, but Grandma was a friend of Nellie’s. Is there a time and place that would be good for us to meet?” “Oh, yes!” came the reply. “I can’t do it tomorrow but Thursday would be good. And we can meet right here at my house. I’ll give you directions.”

My heart was pounding even though I knew, rationally, this might be another person just trying to get on the bandwagon of Lizzie’s notoriety. Any disrespect of Miss Borden was not allowed in my home when I was growing up so I was sensitive to that issue. For that matter, any disrespect of any adult was not allowed. If there were questions about their character I was to hold my tongue and bring those questions to my parents. There, in the sanctity of home, a discussion would be had and the need to deal with anything would be assessed. Now I had to assess the veracity of a stranger on my own as an adult. Beyond that I had to decide if her story had any merit concerning Lizzie. It was not an easy task to decide to take on.

The next day dragged on so slowly and my focus had definitely been shifted to things other than my family and the everyday running of the house. I still didn’t know how much I would tell Ruby Cameron or how much she would share with me. Finally, to get anything done, I had to push thoughts of the meeting to the back of my mind and concentrate on the daily tasks at hand.

“Now, when you come bring some lunch and we’ll chat a good long while.” Words of sunshine to a busy mother with a part time job to boot! Time to just sit and talk! WOW! Not only that, but the subject was one not many in Maine were well versed in or even cared about. Finding a person who not only knew the story but also had personal involvement so close to home was like a gift from heaven. She was that, you know, a gift from heaven.

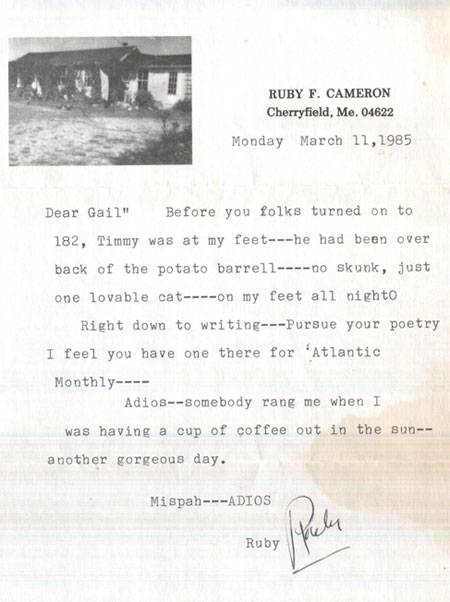

After our meeting, Ruby’s letters were like a conversation on the telephone. She had a thought, put it on paper, and mailed it. There might be two or three in the same mail, although most of the time she tried to conserve postage like most 84 year-old women on a fixed budget. My mailbox lit up with sunshine when a letter from Ruby was there. The part I loved the best was her sign-off, “Mispah, Ruby.” Short, straight, and to the point—facts, orders, or invitations sent about thirty-five miles up the road with a stamp.

She loved life, people, writing, Timmy the cat, and growing tomatoes in the summertime. She liked to fish too, but had put her boat away not long ago. She had thought it was not safe for her to push it in the river and climb aboard anymore. Until then, her evening meal might have been caught that very day from the river that flowed past her back yard. She lived much as I would choose to live at the end of my life, on her own, in a little cabin, with birds chirping, wildflowers blooming, and a kettle on the stove. There was no central heat, just a wood stove fed with logs she had split herself and a kerosene “pot” burner to use only on those days in deep winter when the temperature plummeted way below zero. Friends helped her split the wood now and church folks came to clean her small abode once in a while and help her button the place up for winter. Life in the further reaches of Maine is much the same as it used to be long ago.

Ruby was an instinctive teacher when it came to written English. The world of publishing fascinated her and she tried to impart her pearls of wisdom every time we met. Her eyes were fading but her mind was clear when it came to who, what, where, when and how. If the details seemed a bit garbled in the story she broke to the world it was only because she did not think some things were as important as the reporters did. Of course, that was their job, to get the story straight. She viewed hers as just to tell her story as she remembered it. The weight of carrying it for years had bothered her and now that weight had been lifted. There were things about her personal family that still hurt deeply and those things she did not wish to make public. She really didn’t care about proving every last detail. Proof to herself was not necessary. She had lived it! Believing herself was not in question. Her curiosity never ended, though. She knew the story, but was no wiser than we when it came to motive. She believed it was love that had inspired the murders but had that tiny doubt in her mind, as we all do in ours, that it might have been more. Her perspective had been through Lizzie’s eyes and perhaps not an objective view of what had actually taken place. Never in question was that Lizzie had been in love with David and that she had refused to marry him later, after things had settled down. Never in question was the story Lizzie had told her about David’s frenzy that day in August, 1892. Never in question was Ruby’s love and consideration for her mother, so she left the nursing position with Lizzie to try and quell her mother’s fears. Although she carried guilt about that job ultimately being the cause of her mother’s suicide, she also carried regrets that she did not stay with Lizzie until she passed away.

When there was an item that needed proving or a discrepancy that needed clearing up Ruby became the detective. Reporters came and went and they got what she deemed them worthy of at the moment. Then, when they left with a question unanswered she busily set about finding the answer. They may never have known the outcome, but she did. Ruby was very suspicious of reporters and very few impressed her. One of the reasons for breaking the story in the Ellsworth American was that Ruby had known the personal history of Jack Wiggins. His father had an illustrious career with the Washington Post and had won Ruby’s admiration many years ago. She knew she would be treated with respect and the story would be broken with dignity. She also knew it would start a feeding frenzy in Massachusetts and often chuckled heartily about the papers there having to pick it up off the AP wire. Everyone who contacted her was scrutinized. She would set about finding out who they were and what they were after. She struggled long and hard with the decision to give the story to the Boston Herald. Rupert Murdock was not one of her favorite characters and it almost cost them an interview. In the end she decided to do it because of the distribution numbers. I think she regretted it when she saw that backlit picture they printed with her article, trying to make her look scary and appeal to the crowd interested in making the story into something sensational. I’m sure it sold papers, though.

If something did not strike her just right the fire in her eyes would light and there would be a flurry of action until the problem had been solved. How I loved seeing that fire in her eyes! She became a whirlwind of activity that put this younger woman to shame.

But in that activity was caring and a true love of what she was doing. Her days were full and she never lacked for things to do or people to contact.

Multitasking was not a new concept to her. She taught me much about the publishing world and was writing some short stories. There was a local author doing a workshop at the library and Ruby made sure both of us were there. She had finished a little children’s story and together we were getting it typed in manuscript form so she could submit it. At the time, I was tied up in my growing family and the option of authorship was not high on my priority list. Now I wish it had been. One of my regrets is not following through on some of her suggestions to publish some of my own poetry.

Another regret is never taking any pictures of our time together. The fact that it might end so abruptly never entered my head. Ruby was so full of life it never occurred to me that she might leave this earth one day without advance notice. Pictures were on the list of things to do but there always seemed to be something more important to get done. On my last visit to her little cabin she was not feeling well. She had wanted me to be there because there was someone coming to see her about some publishing matters. She liked having a witness there when such things were discussed. It was obvious she was ill but she conducted the meeting anyway. Then Ruby sent us on our way. I had children coming home from school and had to get there before they did. Otherwise I definitely would have stayed until someone else could have been with her. When I got home I called her neighbor and friend, explained the situation, and asked her to look in on Ruby to be sure she did not need help. The next morning the call came. Her friend had visited until about 6 o’clock when Ruby shooed her out to make supper. Ruby walked her to the door and told her not to come back that evening. She was locking the door and going to bed. Her friend discovered her the next morning when she couldn’t get her to answer. That unexpected call hit me in the pit of my stomach and I cried like she had been my own mother. The emptiness I felt was the same as losing a lifelong friend, but I felt cheated even more because our time had been so short together. There was so much we had left to do and now she was gone.

Her papers disappeared. Her lawyer called looking for them and I was horrified to learn he did not have them. Someone took them who had no right to them and, in my mind, it was robbing the dead. They couldn’t take my memories though, or the picture in my mind of her bright, cheerful face smiling, chattering and scolding with those fiery eyes so full of love.

My mailbox no longer contains Ruby’s sunshine but it will last forever in my heart.

Biographical Note: “Gramma” was born and brought up in Fall River, MA. Her grandmother worked as travelling companion for Miss Lisbeth A. Borden and resided at Maplecroft for approximately two years. Nellie Miller, Miss Borden’s housekeeper, was a close friend of her grandmother, as were Henry and Emily Cook, once employed by Miss Borden as chauffeur and cook, respectively. Gramma’s mother was named by suggestion of Miss Borden for a delightful little girl they met in the lobby of a Washington, DC hotel. Gramma grew up with the story all around her but the most amazing thing was living in Maine, at least eight hours away from Fall River, and learning that another who had grown up even closer to the real truth of the murders was only a little over a half an hour away. They both agreed Lizzie never committed the murders but they both also agreed there was much more to the story than was apparent in the testimony and recorded documents from the trial.