by Kat Koorey

First published in November/December, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 4, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

The phone rang and the householder answered. The caller was a man by the name of Frank Spiering. This name meant nothing to the person who answered, but this name meant something to the caller. In fact, the caller thought rather well of himself and had a way of barging into what he considered a story and taking over. This time he was up against that formidable obstacle, a New England Yankee, born and raised. His intent was to cajole or flatter or plead his way into the house of the recipient of the call. He was coming to Newmarket, New Hampshire to investigate the last whereabouts of Emma Borden, the long-suffering older sister of Lizzie Borden, acquitted hatchet-murderess.

To his credit, he was willing to travel from New York City to at least talk to the townsfolk and get some new anecdotal material for the book he was writing, to be titled Lizzie. To his detraction, he had a history of enlarging upon the truth, and of claiming to have solved mysterious legendary crimes by producing a controversial suspect who experts had disregarded as not relevant, and placing the onus on them. He did this with Jack the Ripper, in his 1978 book, Prince Jack, by naming the culprit as Albert Victor, the grandson of Queen Victoria. He would do it with this Lizzie book (1984) by naming Emma as the murderer of the Bordens, and he would do it in future in his book on the murder of Polly Klaas, Who Killed Polly (1995).

In his youth, Spiering was called a “young man in a hurry” and that tendency can be a detriment to the truth. He was the son of an insurance salesman who made his mark in Hayward, California, by a simple method of self-promotion: he made sure his name made it into his newly adopted town newspaper whenever he could convince the writers to cover his movements.

It was an easy way to gain importance, and his son and namesake learned the lesson well.

Frank Spiering, the younger, was born in Great Falls, Montana, January 12, 1938. In his junior year of high school he was enrolled at Bishop O’Dowd High in Oakland, California, and by graduation he had made a big enough ripple that he was president of the student body, an appointee of the junior city council of Oakland, and junior mayor of the city, year 1955-56.

By the time he spoke at the Lions Club after graduation, he supposedly had amassed quite a large collection of medals, certificates and plaques from speech tournaments.

Frank was slated to attend Notre Dame, in pursuance of a law degree, with post-graduate plans to specialize in foreign law and public relations—at least that was the story told around the Lions Club. Instead, he attended the nearby University of California at Berkeley. His interests were listed as “Fishing, mountain climbing, surfboarding, skin diving and various sexual endeavors.” That may be why he took a pass on Notre Dame.

In 1957 and 1958, Frank’s name seems to have competed for publicity in the Oakland Tribune and the local Hayward Daily Review with his father’s: the former co-launching an actor’s group called the ArtPlayers in the East Bay area with audition calls for singers and dancers, while the latter was a dependable committee member, helping to organize a benefit golf tournament, with Max Baer as a celebrity draw, and participating in a vote drive to elect the Governor of California, Mr. Knight, to the Senate.

Frank wrote a script the summer of 1958 for the new group, called Shadows Off Stage, with its first performance to be a benefit production in aid of St. Paschel’s Parish School—a laudable way to make the paper and fill the house. A news item appeared in 1958 in his local paper, the Daily Review, with a photo of Frank and two other members and next to the piece was an article on Capone’s Story, about a new film with Rod Steiger playing Capone. Years later, in 1976, Spiering published a book on Capone, titled The Man Who Got Capone. Beginning his pattern to single out the odd one as main character, his emphasis was on Frank Wilson, the tax investigator who “got” Capone on tax fraud charges, whereas the world remembered the name of Elliot Ness.

In 1959, Frank received a good review of his acting skills in the play, A Month In The Country, at UC Berkeley. He graduated in 1960 with an A. B. [now a B.A.], while his mother made the papers for her part in a benefit fashion show and his father was noted as co-chair in a drive to raise funds for a Boys Club in Hayward, along with such high officials as the Police Chief and the Fire Chief. That summer, Frank co-wrote songs and sketches for a review called Up For Air, to open at the Playhouse. Who knew the man would become a songwriter, copyrighting as “lyricist” 27 songs, with Richard Wolf accredited as “music,” in the early 1980s? He also co-wrote a musical, titled Durante slated to be directed by Ginger Rogers in the 1980s, which would ever after be considered a work in progress.

Spiering seemed to have loved the stage, considering himself a playwright. There was a lot written about his endeavors in that medium in that time period. Jockeys, a ballet about racing which he co-wrote, made it to off-Broadway in 1977 and was covered by Earl Wilson in all the papers before its debut. Spiering was good at selling himself and his projects and in acquiring backing. Whether the product was any good is another story. The ballet opened with a “sluggish start” and relied on a “baleful script” according to William Glover of the Oakland Tribune.

This was the year Spiering’s first book hit the lists and was assessed in print. He was 39. Brian Alexander reviewed Capone for the Van Nuys paper. He also interviewed the author and garnered snippets of his life story:

Spiering worked briefly as an undercover investigator himself, mainly for insurance companies. His education was in English, but he chose a variety of non-writing jobs—waiter, bartender, investigator—rather than drain his creative energies by writing advertising copy or dabbling in other of the lesser literatures.

The “lesser literatures” paid the bills. He said he was already writing his next book, promising Alexander that it would be on a “controversial subject.” That book would be Prince Jack. On the modern web site, Casebook: Jack the Ripper, Spiering’s name appears. There is the story told, and accepted into lore in “Ripper” circles, that Frank Spiering demanded of Queen Elizabeth II to “open the Royal archives or hold a press release detailing the Duke’s [Albert Victor] activities as the Ripper.” As the Queen did not deign to answer, her spokesman replied that the archives were open to serious researchers, but Spiering backed down. Even in Britain, in 1978, he developed a reputation for promotional stunts.

He married Sarah Elizabeth Farrell on September 15, 1966, and sometime after ended up in New York. In his later years he had an address at 78 West 82nd Street, New York’s Upper West Side. Either his wife was rich or his product sold really well. During the time he was having lackluster luck off-Broadway, he was still writing commercially successful books, including Berserker in 1981. Later, he would write a biography of the Statue of Liberty, called Bearer of a Million Dreams (1986).

His last book, and maybe the most controversial of his repetoire, was Who Killed Polly (1995). The book was published before the Polly Klaas court case had finished. Spiering attended the trial of Richard Allen Davis in San Jose and in February of 1996 he was thrown out of the courtroom for objecting to the sealing of certain evidence by the judge. Apparently he was also promoting his theory of the case, because later he picketed in the plaza outside the courthouse with signs claiming a conspiracy of child sex slave traders. Poor Marc Klaas. He somehow found the fortitude to deal with Spiering’s antics outside while concentrating on convicting the confessed murderer of his child inside. Spiering was ordered by a sheriff’s deputy to get rid of the signs because they might influence the jury, which he did, but he made sure all the newspapers were taken away from the racks as well.

He must have believed in his theory to make such a spectacle at such a vulnerable time and place, but it could also be a part of Frank Spiering’s style—getting his name in the paper and promotion for his book.

He did have talent, but even a reviewer said about him that he was “not a modest person.” The book, this time, was Lizzie (1984), and Dick Case, of the Syracuse Herald American Stars Magazine complained that he “read and reread, the vital passages looking for the author’s evidence. I search for chapter notes, footnotes. Zip. The reader is left with only Spiering’s word . . .” Another reviewer, Florence King of Long Island’s Newsday, was written up in the Washington Post as giving Frank Spiering “five whacks” for what she claimed was “undue similarity” between passages of Spiering’s Lizzie and Victoria Lincoln’s book A Private Disgrace. According to Newsday, when contacted for comment, Spiering was unapologetic and “defended his research.”

In a bitter feud in the pages of The Village Voice, Walter Kendrick gave examples of Spiering’s lifted phrases, and warned readers also that “Spiering, indeed, takes liberties that a conscientious novelist—not to mention any nonfiction writer worthy of the name—would avoid.” Spiering fired back in a letter to the Editor, that the “integrity of my work” had been challenged and then addressed minor factual points in dispute but not the biggest charge of “unsettling similarities.” His final point was to again press his imaginative suspect, Emma, the elder Borden sister, as the “actual killer” and the motive as “Andrew Borden’s fortune.” Kendrick’s response was “I didn’t challenge the integrity of Spiering’s work. It has none,” and continued to say quite a bit more.

Spiering really did not see that he had done anything wrong, or wouldn’t admit it. Spiering continually and consistently promoted himself—and his name in the paper must have made it all worthwhile. A man like that might begin to believe his own hype.

When Spiering made that phone call to the householder in Newmarket from New York, he was met with a firm rejection. He was told not to come and that there was no interest in the Borden story at that address. Maybe the man didn’t know any better. Maybe he was used to getting his way. Maybe he believed he was entitled to the story. He did go, and he was met at the door with disapproval, and made to stand in the rain pleading his case. Eventually he was let in for a few minutes to look around the downstairs and ask a few questions. The result of the visit was more of the same Spiering invention that colors his other notorious projects.

Students of the Borden case have been enriched by his new stories of Emma’s time in Newmarket, but at the expense of truth and accuracy.

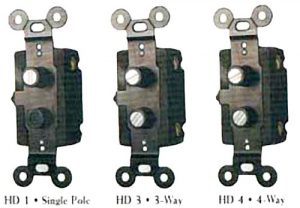

The Light Panel

Spiering wrote that when Emma occupied the Newmarket house she paid for the construction of a second stairway down the back of the house to the kitchen. The stairway was hidden by a closet door, beside which was a narrow auxillary pantry . . . [and] next to the pantry was an extremely unusual lighting panel, which could instantly illuminate the entire downstairs . . . [as] a protective measure.

Actually, the “lighting panel” Spiering refers to is not so unusual, and is not really a “panel” at all. It is merely a larger grouping of switch plates installed in a single area than one might be used to seeing. Upon entering one’s own home, there might be three or four light switches conveniently placed on the wall near the front door. Here, by the rear stairs, there would have been six plates alike, each one designed to accommodate two buttons, one button for light on and one for light off.

The style of these push button plates were the oldest, most common and simplest of the options available in the first half of the 20th century, and were widely used in American homes. What is rare is that most of the Newmarket house lighting switches survived home remodeling, as many did not.

There were originally six mountings with this simple configuration; the homeowner’s father has replaced two of them to suit his more modern taste.

The lower, middle switch is one of these modifications and is probably the most unusual feature of the whole panel. It has the normal, recognizable up/down toggle but incorporates a slide that is a dimmer feature. He had this adjustment made to add an ambiance to his dining room lighting.

The odd-looking plate in the upper right row is also a replacement cover to the original, and is noticeably off-center. It is a switch with a red light above it. This design does impact that stairway to the second floor, but not in any unusual way. The switch illuminates the stairway, and the red light glows as a reminder to the householder that that light was left on, since that back stairs door is always kept closed. One can see by studying the switch plates that they are now out of alignment, which gives evidence of the newer alterations.

Spiering, in his “Author’s note,” claims that “with a single movement,” a paranoid Emma could light the entire downstairs. Actually it is harder to use push buttons, and they are not labeled to designate which room they serve. They are ultimately confusing. It would not be unusual to press them all on, instead of pressing the wrong one first. In fact, the owner, after years of living with this light panel, still pressed an old button and asked if that had lit the porch. Obviously, if this panel was intact during Emma’s residence, it would take six movements to turn on all of the lights downstairs, not just a “single” one.

Spiering invented a legend centered on this light panel and adjacent stairway. When examined, we notice that this is a usual second stairway that happens to be situated towards the middle of the house, rather than in the very back. It has a regular interior door on it that always remains closed. To the right had been a regular kitchen pantry; it is not known that an ax was ever kept there. Next to that door, to the left, is the light panel where all the first floor rooms’ lighting can be accessed. If someone upstairs wanted or needed to flood the downstairs with light before descending, why wasn’t the light panel installed at the top of the stairway? It really is more likely to be situated where it is for the convenience of shutting off all the downstairs lights as one ascends to the bedrooms.

An investigator’s question might be who actually commissioned the “lighting panel?” Spiering is assuming it to be Emma, but it could have been any owner of the house from the turn of the century. Why must he create a mystery when his stated purpose is to solve one? Misusing his talents, he created his own spin to the story of the end of Emma’s life, which has influenced countless readers who place their trust in an author to be truthful in a non-fiction work. That is typical Spiering, who as a young man, wanted to excel in the field of public relations, a benign phrase for spinmeister. The homeowner was right to tell him not to come. We would be missing this new dimension he discovered of Emma’s life in Newmarket, but we also wouldn’t be burdened with unraveling Spiering’s imaginative deceptions.

Works Cited:

Alexander, Brian. “The unsung undercover man who jailed Capone.” Valley News [Van Nuys, CA] 19 August 1977: Section 3.

Case, Dick. “New Lizzie book interesting but unconvincing.” Syracuse Herald American Stars Magazine 26 August 1984: 11, 12.

Contemporary Authors Online. “Frank Spiering.” Gale, 2002.

Glover, William. “Jockey’s, A Ballet About Racing Off to Slow Start.” Oakland Tribune 17 April 1977.

Kendrick, Walter. “Hack Work or Hatchet Job?” Village Voice 10 July 1984: 36.

“Side Views.” The Daily Review [Hayward, CA.] 12 July 1956: 13.

Slung, Michele. “Checking Out A New Novel: The Fact-Checking Department.” Washington Post 8 July 1984.

Spiering, Frank. “Walter Kendrick Took an Ax.” Village Voice 25 July 1984, and Kendrick’s response.

Spiering, Frank. Lizzie. NY: Pinnacle Books, 1984.