by Stefani Koorey

First published in Winter, 2009, Volume 6, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

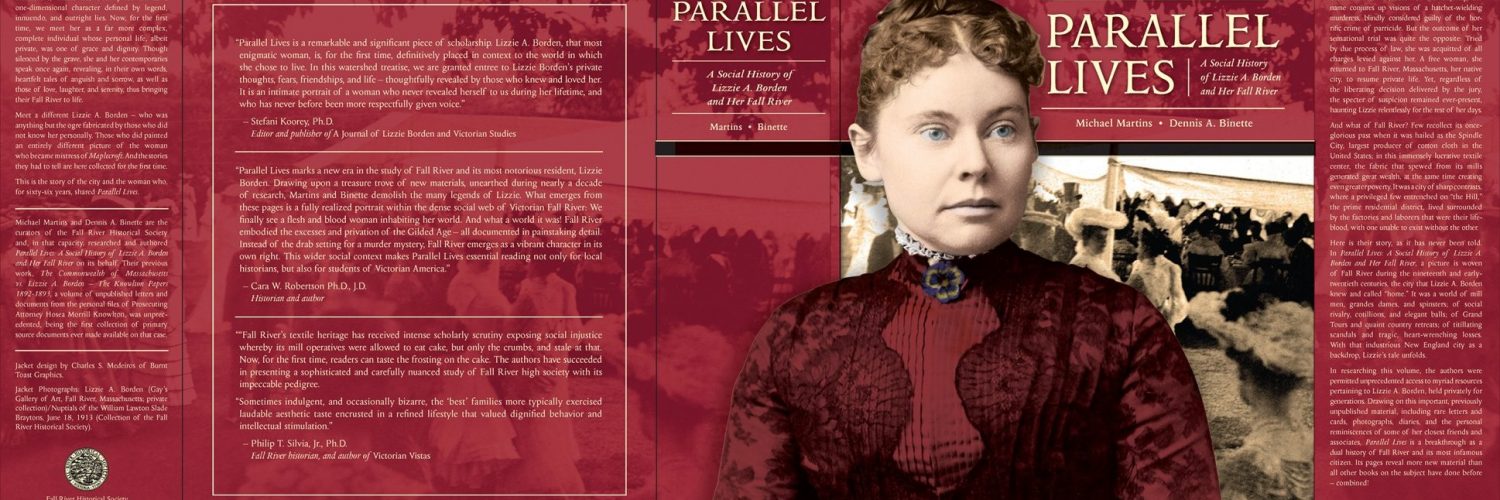

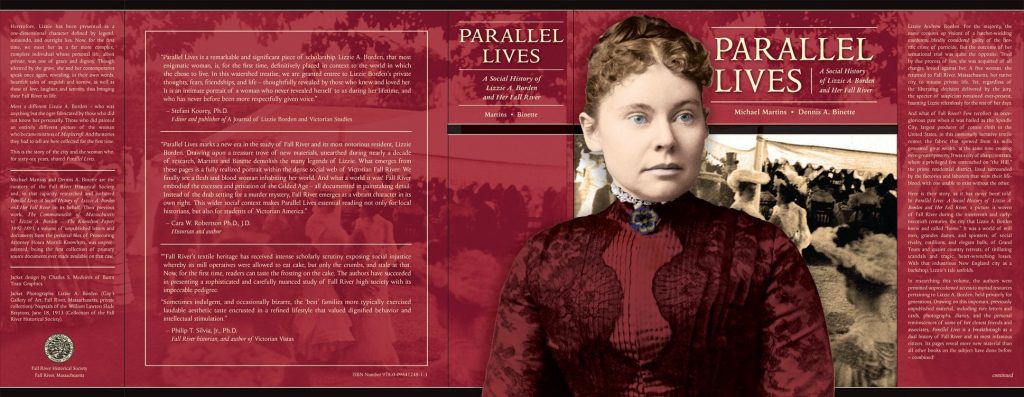

Parallel Lives: A Social History of Lizzie A. Borden and Her Fall River, written by the curators of Fall River Historical Society, and due out later this year, will be sure to please and is definitely worth the long wait. You can be assured that this meticulously-researched and carefully-composed history of Lizzie Borden and the city where she was born and chose to spend her life is overflowing with surprises and new discoveries—enough to satisfy the hunger we all have for significant details on both subjects. And how do I know this? I have read the book!

No, I haven’t laid my hands on some bootlegged copy or stolen pages from the Historical Society’s offices. I have been retained as the indexer of the treatise, and, as such, have been reading it all along, a chapter at a time, as it has been written and typeset, and working to develop a user-friendly but sophisticated back-of-the-book research tool.

While my job as indexer has granted me fortunate access to all of the inside scoops and astonishing finds, it has also given me the rewarding opportunity to assist the curator, Michael Martins, and the assistant curator, Dennis Binette, in editing the material and advising them on matters such as readability, grammar, and syntax. I am not the sole person to be asked to copyedit—Michael and Dennis have enlisted others as well to insure that this book is the best it can conceivably be, and as free from error as practicable.

The index that I have been tasked to create will be an extensive one as the Historical Society and I envision it to be useful to several audiences—the general reading public, researchers, and genealogists. Parallel Lives is about the people of Fall River, with Lizzie Borden figuring prominently, during the years of Lizzie’s life: 1860-1927. There are an enormous number of human dramas playing out between its covers as the city’s history is recounted, and each story centers on the people who experienced them. That means, of course, that the book is teeming with names and relationships, both generational and social, that must be made accessible to the user in a way other than the text can provide.

There is no software or computer-assisted shortcut to create a true index. The only help one can obtain from automation is in the physical formatting of the data collected into a preset design, such as an alphabetical listing. An index is not a concordance, where every word or name is counted and cross-referenced. If we were trying to determine the number of times, for instance, that the word “fire” appears in the book, we could certainly use software that would not only count the use of the word, but could tell us where, exactly, that word is found, whether or not these mentions are significant.

Concordances are most often found on websites, such as those that contain the works of Shakespeare or the texts of dictionaries and famous quotations. It is sometimes useful to have such knowledge, especially when you are looking at the lexiconography of a work or a series of works, or need to locate a specific instance of a word in a large database. The “find” command on your word processing software uses this technology, as do search engines such as Google, Bing, and DogPile. Simply enter a word or phrase and you are rewarded with a list of every website that contains it. The ordering of the relevance of your results is problematical, however, as each search engine operates with a proprietary algorithm that ranks different websites in rather secret ways to determine the ordering of the results.

The possible use for the concordance is limited, with the resultant collection becoming fodder for statistical or numerical examinations—interesting findings in and of themselves, but not something that is sensible for use in locating concepts and subjects not expressly listed in the parent work.

Indexes will probably always require a human being to construct because they are creative works, first and foremost. The Library of Congress’ US Copyright Office deems them to be so and, increasingly, indexes of books are registered for their own copyright, separate from the book’s copyright from which they come.

The reason why indexes need humans to work properly is that so much of what an index is involves thinking outside the box—organizing words into concepts and subjects that a reader might want to use to find what they might want to know! It is the anticipation or prediction, if you will, of what someone is looking for that determines the specifics of just how the index is organized and what subjects to detail. An index is a finding aid, and a really good index will be both accurate and extensive. Names must be cross-referenced so that if you are looking for a woman who married, you would be able to find her under both her maiden and married names. The major events in a person’s life, such as Lizzie Borden’s, would have to be categorized in such a way that makes the search process quick and correct. If you simply want to find information on Lizzie’s educational history, and nothing else, you would first look to the index to get the location within the book where that part of her story is detailed.

Perhaps, also, the index would contain the information you are looking for without necessitating a visit to the text to read the narrative. If you want to know, for instance, the married name of someone, or the names of their children, you can often use an index to determine that data. When we don’t know the full names of individuals, epithets are used that provide their descriptive title or duty. With so many Bordens, Durfees, and Chases populating the history of Fall River, it will be important to specify, when known, their relationship to the story, to each other, to their family, or indicate their significance or accomplishment.

I have quite a bit of experience creating indexes, having constructed them for each of my published works. One of my books is an annotated bibliography of playwright Arthur Miller, and is over 900 pages in length. The index for this massive research book is in two sections—a name index and a subject index. I deemed it imperative that these two methods of organization be separated so as not to clutter the index and make it difficult and time consuming to use. I approached the crafting of the index as if I were a reader or researcher, putting myself in the shoes of the seeker. How might I approach the content if I don’t want to read the whole thing? How could I not only find where in the book Miller’s marriage to Marilyn Monroe is mentioned (using the name index), but also how she figured into Miller’s work thematically (subject index).

A proper index is not easy to construct, is unbelievably time-consuming, and requires super-human attention to detail. I am sure you have encountered both good and bad examples of them in your reading. When I use a book for research and cannot locate the information I need on the fly, like a quote or a date, it drives me insane! I have been known to scream at a book that does not have a complete or accurate index. Poorly created indexes are the bane of every researcher.

Did you notice that Sarah Palin’s book, Going Rogue, did not have an index? The publisher felt that hers was a book that would be picked up by a lot of people who were looking to see if they were mentioned in it, and if they found they were not, or simply went to the section they were in and read that portion only, that they would not purchase the book and put it back on the shelf! And this plan worked. Everyone who was anyone connected with both presidential campaigns had to buy the book, and read the book, to see if they were in there. In addition, the news agencies and reporters who were covering the book’s release were also forced to read to discover if so-and-so or such-and-such was discussed. This trick created a lot of buzz, but also a lot of ill will. Future editions of the book, promises the publisher, will contain an index.

The index is the last thing that is written before a book is published. It has to be. The index can only be created once a chapter is typeset because accurate pagination is vital to the process. A gifted indexer can create an index for a 400-page non-fiction book in about three weeks. Parallel Lives is probably going to top out at close to 1,000 pages, with over 500 photographs and illustrations. Its massive size is one reason why the project was begun as each chapter has been made ready for printing, in smaller increments. It will shorten the time necessary at the end stage of the writing process, and not hold up the publication.

Another important point to make is that an indexer must read and re-read the book they are going to work on so they can more accurately understand its context and subject matter. How else could the content be indexed without a deep knowledge of a book’s terminology and approach to a subject? It is fortunate that I am well versed in the history of Fall River and Lizzie Borden, and this has served me well while doing this work. However, it is even more important, I think, that I have read the work several times, once for editing assistance, once for help in proofreading the typeset chapters for errors, and now a third time to index. Obviously, indexing is not a job for the lazy or the sloppy.

The size or length of an index depends on several important factors, not the least of which is the editor’s requirements for page length for the entire book. In publishing, a book is arranged so that it has an even number of signatures. A signature is a group of 16 pages that have been cut and folded from one large sheet of paper, or press sheet. The press shee tmight be 49 inches by 37 inches, containing 32 pages per side. If the publication editor has only a limited space for the index, then it must somehow fit within the printing parameters. If not, two extra signatures must be added to the book, raising the cost per volume rather significantly.

So, then, how do indexers and publishers estimate the size of an index? The answer is a bit technical, but interesting still the same. It depends on the type of book and the average number of entries that genre usually contains on a per page basis. A good rule of thumb is that a mass market trade book that is not heavy on the facts has a percentage of index pages of 2-5%, or 3-5 entries per page. A college textbook, cookbook, scholarly book, or general reference work has a percentage of index pages at about 7-8%, or 6-8 entries per page. A user-manual or technical book might have as high a percentage of index pages at 10%, or 8-10 entries per page. Codes and regulations and service and repair books have the highest percentage of index pages at 15+%, or 10+ entries per page.

Parallel Lives is a comprehensive historical work with a large number of indexable entries per page. Using the rule of thumb, the completed index might be anywhere from 50-80 pages long. So you can see I have my work cut out for me, and how important it is for this book to have a great index. It will be up to you to judge whether I succeed or fail. My goal is not to have any of you curse me as you are trying to find what you are looking for in the index of your copy of Parallel Lives!