by Stefani Koorey, PhD

First published in Spring, 2012, Volume 7, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

The November 2008 issue of The Hatchet featured an article by Jerry Ross about his trip to Montana to visit the places where Bridget Sullivan, the maid at the time of the infamous Borden murders of 1892, lived after she left Fall River, Massachusetts, and to pay his respects at her final resting place. During the editing of that work, and while verifying some of the information Jerry presented, I was excited to discover that Bridget had some family still living in that part of the country (after all, she died in 1948, which is fairly recent in terms of the Borden story, and she came from a large family). The Hatchet was not able to include this newfound material because it had yet to be developed. Inspired by Jerry’s story, I have continued the quest for the family lore and historical truth of her life, which I will publish in a full-length book on Bridget Sullivan and the story of the Irish immigrant in Butte and Anaconda, Montana.

The November 2008 issue of The Hatchet featured an article by Jerry Ross about his trip to Montana to visit the places where Bridget Sullivan, the maid at the time of the infamous Borden murders of 1892, lived after she left Fall River, Massachusetts, and to pay his respects at her final resting place. During the editing of that work, and while verifying some of the information Jerry presented, I was excited to discover that Bridget had some family still living in that part of the country (after all, she died in 1948, which is fairly recent in terms of the Borden story, and she came from a large family). The Hatchet was not able to include this newfound material because it had yet to be developed. Inspired by Jerry’s story, I have continued the quest for the family lore and historical truth of her life, which I will publish in a full-length book on Bridget Sullivan and the story of the Irish immigrant in Butte and Anaconda, Montana.

Much has been written about the Irish story of mass immigration to the United States during the Great Hunger (Potato Famine of 1845-1849), a time of immense suffering that affected huge numbers of Irish people. Yet, surprisingly, it is in the post-Famine years that America saw the greatest influx of Irish, with 3.1 million migrating in the years between 1856 and 1921 (Emmons 1-2). Many settled in the copper-mining center of the world, Butte, Montana, and a considerable percentage of Butte’s Irishmen came from mining regions in Ireland, like West Cork, the birthplace of Bridget Sullivan. According to David Emmons in his seminal work, The Butte Irish, “County Cork in southwestern Ireland supplied a hugely disproportionate share of Butte’s Irish population” (15).

Most of the Irishmen and Irishwomen who came to Butte were under thirty, and a significant percentage were unmarried at the time of their emigration. Marriage, particularly to another Irish Catholic, was a significant part of the process of settling into Butte’s Irish community; but marriage, like the general process of which it was a part, was postponed until the town and its work opportunities had proven themselves (Emmons 14).

While the Butte Irish story is fairly well documented, the lives of individual immigrants are less so. Unlike Lizzie Borden, Bridget Sullivan is especially invisible to history, preferring to live out the bulk of her life in a community where she could almost disappear among her fellow countrymen—there were over 1,200 Sullivans in Butte in 1908. According to Emmons, members of at least 77 different Sullivan families emigrated from Castletownbere, Ireland, to Butte, Montana, and the six most common Irish surnames there during the representative years of 1886, 1892, 1897, 1902, 1908, and 1914, were Sullivan, Harrington, Murphy, Kelly, Shea, and O’Neill (15).

Anaconda, Montana, twenty miles from Butte, proved to be far enough away from Fall River for Bridget to be able to anonymously enjoy a life unencumbered by publicity or prying newspaper reporters. And just as Lizzie Borden refused to discuss the crimes that made her name known worldwide, so also did Bridget Sullivan choose never to mention, in any specific way, her association with what has come to be known as the “crime of the century.” Even members of Bridget’s own family were surprised, years later, to learn that their relative was that Bridget Sullivan.

To construct the narrative of this woman whose name once appeared in newspapers across the country, but who later “disappeared” from sight, research has to be done the old fashioned way—conducting interviews, following lines of investigation, sifting through genealogical databases and accounts of events by others—all the while verifying every detail so as not to add to the already distorted history of the Borden murder case or the life of Bridget Sullivan.

In far too many examples, what has been written about Bridget Sullivan is filled with errors, whether a result of reckless research or simply a case of mistaken identity—an easily understandable error. Even the historical society of Anaconda misidentified her in a very public way, mistaking Bridget for a woman with the same name. Add to this the fact that Bridget married an Irishman in Montana with the same last name. As the joke goes, at least she didn’t have to change the monogram on the linens! But this makes for a genealogical tangle that is difficult to unravel, especially when examining passenger lists for travel to and from Ireland. I needed to be a combination of detective, researcher, analyst, and code breaker, with an advanced degree in common sense, to make an accurate chronicle of Bridget’s whereabouts during her life.

There are only Bridget’s own documented sworn statements during legal proceedings against Lizzie Borden that chronicle her past employment and time in America since her immigration, to aid in forming an initial time line. City directories before 1900 are not helpful because they generally do not contain the names of servants, unless they happen to be male and residing separately from their employer. Bridget stated in her testimony that she worked for a year in Newport, Rhode Island, at the Perry House, but there is no evidence yet to verify her story, though it may very well be true. Additionally, Bridget repeatedly asserted that she lived and worked in South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, when she first came to the United States, and had relatives there. Once again there is a dead end when examining the directories of that town, as there are no Bridget Sullivans listed.

In order to piece together Bridget’s story, it is helpful to start with an examination of her testimony at the preliminary hearing and the trial, legal documents (her will, marriage license, death certificate, etc.), newspaper accounts, and all of the major nonfiction books on the Borden murder case. There is a need to determine a probable sequence of events: where she lived, when, and for how long; why she moved from place to place; when, if ever, she returned to Ireland, etc. Nothing should be taken at its face value, for experience teaches, with this case especially, that much of what has been written is not necessarily accurate or related truthfully.

Complications Abound

It is likely that Bridget Sullivan did not even know the year of her own birth! This is noticed when her statements about her origins are compared to legal documents and census records. It is not known for certain if Bridget simply didn’t know when she was born or if she was asserting a right to privacy and expressing her distrust of authority by not giving an accurate accounting when asked. According to her relatives, however, not knowing one’s year of birth was common in large Irish families, to which Bridget belonged, due to the intense poverty that precluded the celebration of birthdays. Bridget Sullivan was one of twelve children, which was not an uncommon occurrence. And yet, it is striking that coming from so large a family, Bridget Sullivan had no children of her own.

While there is a wealth of material to begin an investigation, unfortunately there is a missing piece of evidence: the first volume of the Inquest, dated from late August 1892. This is a document that contained both Lizzie and Bridget’s sworn answers to questions about the week of August 4th and the goings on in the Borden family. It is known from the Knowlton Papers that the prosecution was willing to turn over a copy of Bridget’s inquest to the defense, but they were unable to locate it in their files (or so the defense was told). In a letter to District Attorney Pillsbury, dated May 5, 1893, Knowlton states that he “declined to give it to them before the indictment, but I see no objection to giving it to them now. It is almost identical with her story as told before Judge Blaisdell, and will do us no harm” (176).

Scholars are forced to take Knowlton at his word that what Bridget said at the preliminary hearing was “almost identical” to her inquest testimony. But it should be considered that he might have been referring to matters of the case and not to any biographical inquiry into her life. It could very well be that in introducing Bridget Sullivan to the court, both the prosecution and the defense had broached many more personal matters with her than what we find in later sworn statements.

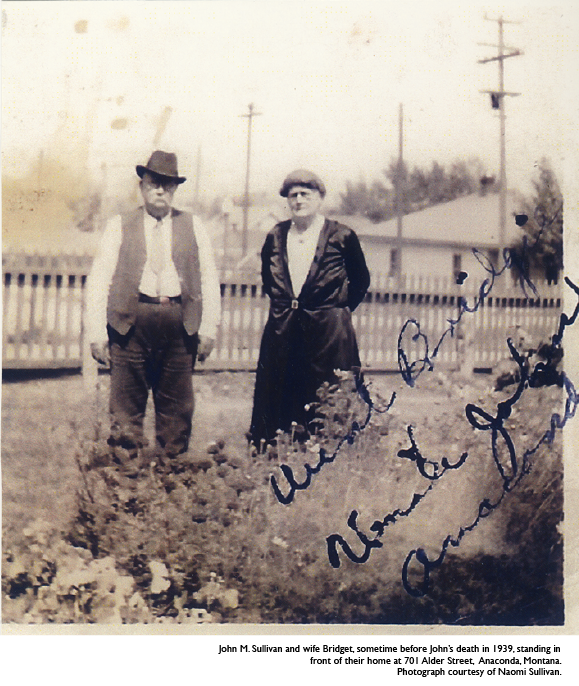

I was assisted in my understanding of Bridget’s family tree by relatives who were concurrently searching for Bridget’s history, and by relatives of Bridget’s husband John, who contacted me through my Lizzie Borden website. We shared family photos, notes, articles, leads, and resources, and continue, to this day, to forge ahead on all things Bridget. Without their help, this work would not be possible.

This introductory article will focus on Bridget’s trip back to Ireland following the trial of Lizzie Borden, as well as her return voyage, which led her to her new home, and new life, in Anaconda, Montana.

One Small Step

It all started with a tiny blurb in the Barnstable Patriot. My friend, and fellow Borden researcher, Harry Widdows, excitedly emailed me his find. The small clipping was dated 20 May 1895, and in it appears this single sentence: “Bridget Sullivan, the witness in the Lizzie Borden trial, sailed for Ireland on the Lucania Saturday.” Saturday of that month and year was May 18, so it was simply a matter of finding that ship’s passenger list on Ancestry.com to find Bridget’s exact departure from the United States and her arrival in Ireland.

Harry Widdows further found an article that noted that the RMS Lucania made history on that trip, setting an eastbound crossing record of five and a half days. This from the New York Times of 25 May 1895:

Queenstown, May 24.—The steamer Lucania, from New-York, arrived here at 6:55 o’clock this morning, having covered 2,897 miles in 5 days 11 hours and 40 minutes, which establishes a record for the long route.

Her daily runs were 431, 505, 524, 522, 517, and 398 miles. On May 22, in latitude 48°, longitude 28°, she passed a submerged wreck, six feet of which were visible above water. The wreck was in a position dangerous to navigation.

Photograph courtesy of Wyn and Stacy Holmes.

The Ancestry record for this trip is incorrect in that they list the name of the ship as Lueania instead of Lucania. Regardless, it is now known that the ship’s port of departure was New York, New York, and the final port of arrival was Liverpool, England. Bridget is listed on the “Names and Descriptions of Passengers” form as being 26 years old, of Irish descent, a servant by occupation, traveling steerage, and with a final destination of Queenstown, Ireland (the port is now named Cobh). According to an advertisement for the Cunard Line, the steamship company who owned the vessel, the Lucania departed from “Pier 40 North River, foot of Clarkson Street, with a destination of Liverpool, via Queenstown.” Cabin passage was “$60 and upward; second cabin, $35, $40, $45, according to steamer and accommodations. Steerage tickets to and from all parts of Europe at very low rates.” Earlier, in 1890, the price for steerage was $16.50.

The RMS Lucania, a 12,950 gross register ton Cunard Line ship, was built by the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company in Govan, Scotland, for Liverpool to New York service, and launched on 2 February 1893. She measured 622 feet in length and possessed a 65 foot 3 inch beam. Her service speed was 22 knots (25.3 mph) and her top speed was 23.5 knots (27 mph), propelled by two triple blade propellers. She had two five-cylinder triple expansion engines producing 31,000 ihp (23,000 kW)—the largest in the world at that time—with 12 double-ended Scotch boilers, 2 funnels, and 102 furnaces, manned by a crew of 424. Her capacity was 2,000 total passengers, of which 600 were first class, 400 were second class, and 1,000 third class.

The RMS Lucania and her sister RMS Campania (launched 8 September 1892) were both built for speed and opulence. On her maiden voyage (2 September 1893) the Lucania set a new record crossing from Liverpool to New York, breaking the record of the Campania.

In his book,Victorian and Edwardian Merchant Steamships from Old Photographs, maritime historian Basil Greenhill stated that the interiors of Lucania and Campania represented the ultimate expression of the Victorian age, and remarked that later vessels’ interiors degenerated into “grandiose vulgarity, the classical syntax debased to mere jargon.” From The Cunard Passenger Log Book: A Short History of the Cunard Steamship Company and A Description of the Royal Mail Steamers Campania and Lucania with Numerous Illustrations and Chart for Recording Daily Runs (1893), we learn that:

Photograph courtesy of Wyn and Stacy Holmes.

There are rooms to suit all tastes in the ship. A large number of single berth cabins are, as we have said, provided, and many double cabins, together with several three or four berth rooms, while family apartments are provided in addition to magnificently appointed suites on the upper deck. Several of these ensuit [sic] rooms are fitted in the most beautiful satinwood and mahogany. They are arranged as parlour and bedroom, the parlour being fitted with table, couch, and chair, on the model of a lady’s boudoir, with suitable decorations.

But this luxury was not at all part of Bridget’s experience on her voyage as a steerage passenger. The same pamphlet offers this information to those who are paying the least for their transatlantic travel:

The Steerage passengers, of whom from 600 to 1,000 may be carried, are accommodated on the lower deck. Iron portable berths are provided. These passengers will be allowed to promenade on upper deck, the circuit of which five times makes a one-mile walk, so that, in this respect, they are very favourably situated. Each compartment of the steerage has a pantry for the special use of the passengers located therein.

Did She Or Didn’t She?

Since Bridget and John Sullivan had no children, the relatives that I have been in touch with are descendents of both her and John’s siblings. Sullivan family lore has it that Bridget traveled back to Ireland directly following her appearance at Lizzie’s trial and purchased a small farm with the $5,000 that they say Bridget was paid by the Borden sisters for her silence. Until now, it was never proven that Bridget had returned to Ireland at all. But since she obviously traveled the least expensive way possible, it could be argued that she did not go back to Ireland a wealthy woman. Until further research into Irish land transactions can be conducted (probably in person with a trip to the Emerald Isle), the story of the purchase of a farm cannot yet be verified.

However, Irish history is clear that until 1900, individuals could not own farms in Ireland. The feudal system was still very much in place, with regions being designated by Baronies. Where Bridget’s family was from, Billeragh (Kilnamanagh, Cork), the Barony was Bear, which covered the northwesterly portion of the county. The Irish Land League was formed specifically to abolish landlordism in Ireland, reduce “rack-rents,” and provide a pathway for families to own the land they worked on. It wasn’t until 1902, when the Land Conference created the Land (Purchase) Act of 1903, that Irish tenant farmers could become landowners by purchasing their freeholds with government loans. For this reason alone, it is probable, then, that Bridget did not return to purchase a farm for her parents.

The Irish census of 1901 shows us that there is no one by the name Eugene (Owen) or Margaret O’Sullivan (or Sullivan)—Bridget’s parents—residing in Billeragh. We find listings for many of her siblings and extended family, but nothing for her parents. Could it be that they were both deceased by the time the census was taken? Or perhaps Bridget returned because one or both of them were ill or had recently passed away. Further investigation of their dates of death should prove illuminating.

The Irish census of 1901 shows us that there is no one by the name Eugene (Owen) or Margaret O’Sullivan (or Sullivan)—Bridget’s parents—residing in Billeragh. We find listings for many of her siblings and extended family, but nothing for her parents. Could it be that they were both deceased by the time the census was taken? Or perhaps Bridget returned because one or both of them were ill or had recently passed away. Further investigation of their dates of death should prove illuminating.

As for Bridget’s trip back to the United States, it is known that she was living in Montana in 1900 by the time the United States census was conducted. By a process of elimination, I have determined when Bridget returned to the States. Eliminating married women, women traveling with infants, those born outside the time frame of Bridget’s probable age, those with the final destinations of Connecticut and New Jersey, any with careers other than servant, and only including those who were of Irish decent, traveling from Queenstown, Ireland, and born between 1865 and 1872, I have found but one candidate: the Bridget Sullivan who is the focus of this essay, returned on the White Star Line SS Britannic (the first of three ships by that name) on 28 February 1896. She had been home in Ireland but nine months.

Had her plans been to stay and live her life out in Ireland? What changed her mind to return to the United States? Or was her initial trip to her homeland just an intentionally temporary visit? Were there fears that kept her away from New England, and what were the circumstances that delivered her to Montana? These are not easy questions to answer about a woman who died almost 65 years ago and whose pivotal historical significance dates back to the late 1800s. With a more in depth study and concentrated search, I hope to be lucky enough to uncover the truth of Bridget Sullivan.

Works Cited

Barnstable Patriot. 20 May 1895. Web. 25 May 2012. Print.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts VS. Lizzie A. Borden; The Knowlton Papers, 1892-1893. Eds. Michael Martins and Dennis A. Binette. Fall River, MA: Fall River Historical Society, 1994. Print.

“The Cunard Passenger Log Book: A Short History of the Cunard Steamship Company and A Description of the Royal Mail Steamers Campania and Lucania with Numerous Illustrations and Chart for Recording Daily Runs, 1893.” Gjenvick.com. n.d. Web. 25 May 2012.

Emmons, David M. The Butte Irish: Class and Ethnicity in an American Mining Town, 1875-1925. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1990. Print.

Greenhill, Basil and Ann Giffard. Victorian and Edwardian Merchant Steamships from Old Photographs. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1979. Print.

The Irish Democratic League of Great Britain. n.d. Web. 25 May 2012.

New York Times. 25 May 1895. Web. 25 May 2012. Print.