by Denise Noe

First published in February/March, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

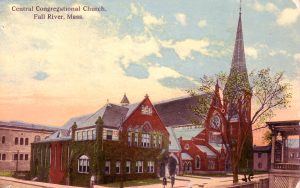

As any student of the Borden case knows, Lizzie Borden regularly attended Fall River’s Central Congregational Church prior to the murders. It was a major part of her life and she appears to have played a dynamic role in it. In Lizzie Borden Past & Present, Leonard Rebello writes that Lizzie joined the church in 1885 when she would have been 25 years old. Lizzie Borden was a dependable parishioner who apparently took an enthusiastic and conscientious part in church activities.

As any student of the Borden case knows, Lizzie Borden regularly attended Fall River’s Central Congregational Church prior to the murders. It was a major part of her life and she appears to have played a dynamic role in it. In Lizzie Borden Past & Present, Leonard Rebello writes that Lizzie joined the church in 1885 when she would have been 25 years old. Lizzie Borden was a dependable parishioner who apparently took an enthusiastic and conscientious part in church activities.

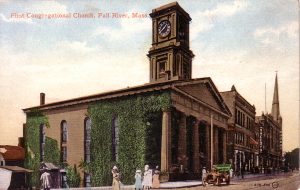

Andrew had attended the First Congregational Church as a young man. This writer was unable to discover the reason that he changed from that church to another of the same denomination—the Central Congregational Church—but does not believe it was for convenience based on location. Much later in life he switched back; rumor had the reason as a financial disagreement with another member.

Andrew had attended the First Congregational Church as a young man. This writer was unable to discover the reason that he changed from that church to another of the same denomination—the Central Congregational Church—but does not believe it was for convenience based on location. Much later in life he switched back; rumor had the reason as a financial disagreement with another member.

At Lizzie’s trial, the defense called fellow Congregational Church member Marianna Holmes to the stand. She testified that Lizzie “was a member of the Christian Endeavor Society,” and taught in the Chinese department of the Bible class of the Sunday school.

After returning home from their European tour, Lizzie and sisters Carrie and Anna Borden were given a reception at the church. An article about that reception appeared in the November 11, 1890 issue of the Fall River Evening News. The article stated that the reception included music, refreshments, and toasts and that the area in which it took place was cheerfully decorated with potted and cut flowers.

Rev. William Walker Jubb was the pastor of the Central Congregational Church at the time of the murders. He had held that position for slightly less than a year, having been installed as its minister on September 29, 1891. A native of England, he had visited America in 1881 and returned in 1891, where he visited Boston and friends introduced him to the Congregational Church in Fall River—a church that needed a pastor. The church offered him the position and he accepted. He must have been an asset to it as Rebello quotes members of the congregation describing him as “a man of great ability, eloquent as a speaker . . . a persuasive orator, genial and sympathetic.”

Rebello states that Rev. Jubb had been a Methodist when he began preaching back in England, and then switched denominations to Congregationalism.

What is special about this denomination? According to the Encyclopedia of Religion, Congregationalism began in England in the late 16th century. When the denomination was first forming, Congregationalists were often called Independents. Its major emphases have been on the right and responsibility of each congregation to make decisions about its own affairs and on the freedom of conscience. The Encyclopedia states that they also emphasize “the free movement of the Holy Spirit, which gives them some affinity with the Quakers as well as with Presbyterians.”

Congregationalists placed great value on the importance of preaching with their only official sacraments being baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Hymns played a particularly vital role in its services. In 1952, the English Congregational Praise was compiled and is considered by experts to be an excellent book of hymns.

The Church’s strong advocacy of freedom of conscience led it to support protection for the rights of minorities. Perhaps this advocacy is one of the reasons that, in both England and America, Congregationalism was one of the first denominations to admit women into the ministry.

In England, many “Independents” were influential during the English Civil War that raged from 1642 to 1651 and enjoyed a particularly strong representation in the army. The movement suffered a severe setback with the restoration of Charles II in 1660. In his reign, the Act of Uniformity of 1662 worked to suppress them although its primary targets were Presbyterian ministers.

Congregationalists enjoyed greater freedom when William and Mary ascended the throne in 1688. During the 18th Century, Congregationalists had their own spiritual upsurge that was probably influenced by the Methodist revival. In 1795, Congregationalists formed the London Missionary Society that established Congregationalist churches in many areas of the world including Africa, India, China and Polynesia.

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions that promoted missionary work in the Far East beginning in 1810 was composed mainly of Congregationalists.

The 19th Century was a time of great activism and widespread acceptance of Congregationalism. A national organization in England, the Congregational Union, formed in 1832 to serve as an umbrella association for English Congregational Churches. Many church buildings were constructed and Congregationalist ministers often became well known.

Congregationalism continued to surge in popularity and public respect in England until the early 20th Century. During World War I, this denomination, along with several others, saw a decline in membership. In 1972, most English Congregationalist churches merged with the Presbyterian Church to form the United Reformed Church.

The United States proved an especially hospitable environment for Congregationalism. Its numbers and public influence in America surpassed those of the church in its English birthplace. Congregationalists were prominent in the founding of some of America’s most distinguished institutions of higher learning including Harvard College and Yale University. As was true in England, the U.S. saw a rise in Congregationalism during the 19th Century so the Bordens belonged to a popular and widely respected branch of Christianity.

Congregationalism has focused and worked toward ecumenicalism. In 1961, it merged with the Evangelical and Reformed Church to form the United Church of Christ.

Henry M. Fenner authored a History of Fall River that discusses the formation and early history of the local Central Congregational Church. Fenner writes that the First Congregational Church was “the mother of the Central Church.” Fenner continues that seventy members of the First Congregational Church, disaffected due to “a business disagreement between two prominent members,” withdrew from the mother church to found the Central Congregational Church on November 16, 1842.

The newly formed congregation met at members’ homes until a facility called the Pocasset Building was secured. A fire destroyed that building and the group began holding services in a Baptist Temple. Finally, according to Fenner, “it was able to occupy the vestry of a new wooden edifice it had erected . . . [at] Bedford and Rock streets, on land donated for the purpose by the Durfee family.” This building was dedicated in 1844. Rev. Samuel Washburn was its first pastor and it started out with 106 members. Rev. Washburn officiated at the wedding of Andrew Borden and Sarah Morse on December 25, 1845.

Arthur Phillips, an attorney who worked under Andrew Jennings during Lizzie’s trial, wrote The Phillips History of Fall River, in which he discusses the formation of the Central Congregational Church. His history agrees with that already given but adds interesting details about the church’s outreach programs. According to Phillips, the wife of Col. Richard Borden was at a women’s prayer meeting for foreign missions held in the vestry of the old Central Church on Bedford Street in 1849 when she asked, “Are there no heathen about us, who need to be saved?” Her simple question was taken as a challenge that led the church to eventually form both its Pleasant Street Mission and its Boys’ Club. These organizations in turn led to fruitful alliances between this church and others. Phillips writes, “The efforts of interested members of the Central Church to reach the neglected children of the community attracted the attention of other denominations and a number of people from the several churches organized the Fall River Domestic Missionary Society.”

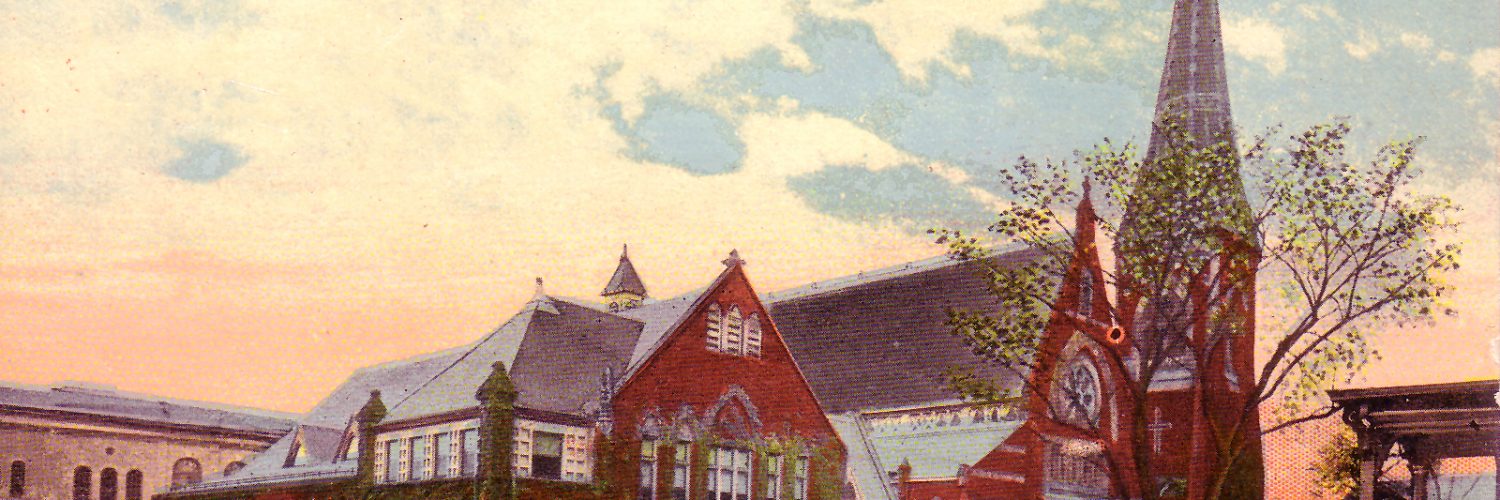

The construction of the new (and present) church on Rock and Franklin streets was begun in May 1874 and was dedicated December 13, 1875. Fenner describes it as a physically impressive and invitingly attractive building: “It is of brick, with Nova Scotia freestone trimmings, and is in the Victoria Early English Gothic style. It has a regular seating capacity of 1,200, which may be increased when necessary to 1,800. Over $125,000 had been subscribed for the building fund, including two gifts of $40,000 each from Dr. Nathan Durfee and Colonel Richard Borden, but the completion of the structure left the church with the old property on its hands and a debt of $100,000. This was a heavy burden, but was carried until Sunday, February 1, 1880, when $76,000 was raised in a single day. The original church property was sold in 1886, together with other land, and the church became and has since remained free from debt.”

As a pastor of the church, Rev. Washburn (1844-49), was followed by Rev. Eli Thurston (1849-69), then Rev. Michael Burnham (1870-82), then Rev. Eldridge Mix (1882-90), and then Rev. William Walker Jubb (1891-96).

According to Phillips, the Central Church’s Mission School called Rev. E. A. Buck on October 27, 1867 and asked him to become its missionary. Phillips gives Rev. Buck’s mottos as: “Help whomever, Whenever you can! Man forever, Needs help from man.” The busy Rev. Buck also became president of the Boys Club that was established in 1890.

Rev. Buck would play an important role in both Lizzie’s and Emma’s lives so it is worthwhile to know his background. Rebello gives his full name as Edwin Augustus Buck and notes that he was born in Bucksport, Maine on May 31, 1824. His parents were James Buck and Lydia Treat Buck. His father was from Bucksport, Maine and Rebello states that the similarity of name was no coincidence as Rev. Buck’s great grandfather Jonathan founded the town.

At 14, Edwin Buck traveled to Bangor, Maine where he got a job clerking in a general store. In an odd coincidence for one who was to play a significant role in the Borden case, his life was radically changed by an apparently badly wounding accident with an ax he was using for chopping. Perhaps the injury led him to reflect upon his own mortality and that of humanity in general. Additionally, the time laid up may have led to more serious thought about exactly what he wanted to do with his life. He apparently determined to become either a teacher or a minister.

Buck decided he needed a higher education to meet these goals. He attended the Phillips Andover Academy and then Yale University from which he graduated in 1849. He started his religious higher education at the Andover Theological Seminary in 1850 and then transferred to the Bangor Theological Seminary from which he graduated in 1853. Rev. Buck married Elmira R. Walker who bore six children during the marriage, five girls and one boy.

On May 31, 1854, Rev. Buck was ordained and became the minister for the Congregational Church in Bethel, Maine. He served at that church until 1859 when he became the pastor at the Congregational Church in Slatersville, Rhode Island, and served there until the end of 1867. He accepted the position of city missionary at Fall River’s Central Congregational Church where he would have come to know the Bordens.

Prior to the murders, Lizzie planned to join a group of ladies on a vacation to Marion. Lizzie never went on this trip, but if she had, one of the women she would have met up with was Alice Lydia Buck, a daughter of Rev. Buck, so it appears that Lizzie was friendly with the Buck family.

In the immediate aftermath of the Borden murders, a Central Congregational Church organization in which Lizzie had been active, the Young People’s Society of Christian Endeavor, passed a resolution that they sent to her along with flowers. Rebello quotes an August 15, 1892 article in the Fall River Daily Herald as reporting that the resolution read as follows: “We, the members of the Young People’s Society of Christian Endeavor, desire to express to our fellow member, Miss Lizzie A. Borden, our sincere sympathy with her in her present hour of trial, and our confident belief that she will soon be restored to her former place of usefulness among us.”

Rev. Jubb also steadfastly supported Lizzie. Ann Jones in Women Who Kill quotes him as asking his congregation, “Where is the motive? When men resort to crime it is for plunder, for gain, from enmity, in sudden anger or for revenge. Strangely, nothing of this nature enters into this case, and again I ask—what was the motive?”

Rev. Buck conducted the funeral services for Andrew and Abby Borden, reading from the famous New Testament passage, “I am the resurrection and the life.”

Rev. Buck also came to Lizzie’s aid in this time of (literal) trial. He visited her during her imprisonment in Fall River and Taunton, Massachusetts. He oftentimes provided Lizzie with spiritual guidance and brought her books to read. He attended the preliminary hearing and the trial itself. He publicly championed her innocence. He gave an interview to the New Bedford Daily Mercury, published August 13, 1892, according to Rebello, in which Buck stated, “Both sisters are very much prostrated, but I think they are bearing up remarkably under the strain. Lizzie was surprisingly composed and self possessed this morning, and much better than I expected. Lizzie protests her innocence, but beyond the hope and expectation of being acquitted, she will talk very little about the arrest. I am confident of her exoneration.”

When she was acquitted, the Boston Daily Globe of 21 June, 1893, as reported in Rebello, gave several prominent men’s opinions of the verdict. Rev. Buck said, “I am delighted beyond expression. After Mr. Knowlton’s awful presentation of the case, I hardly expected a verdict so soon.” However, this statement seems somewhat confusing. By “awful presentation,” did Rev. Buck mean to say Knowlton did a poor job? If so, it seems the quick not guilty verdict would reasonably be expected. Or did he mean to indicate that the “awful presentation” was one that would greatly horrify? Perhaps the emotionality of the moment caused the minister to garble his expression.

The support of the Central Congregational Church, or at least of its rank-and-file members, like so much of the backing Lizzie received, may have evaporated after her acquittal.

Rebello quotes Lizzie’s close and loyal friend Helen Leighton as saying in an interview with the Fall River Herald, “She went to church but once after her acquittal, the Congregational church in which she had been an active worker for years.” Considering the importance this institution had played in Lizzie’s life, it seems unlikely she would quit attending unless that final Sunday visit had been a disaster for her.

Rev. Jubb, who had so strongly defended Lizzie from the pulpit, continued preaching at the Central Congregational Church for three more years. He resigned in 1896 to return to his native England where he died on March 4, 1904. We can only wonder if, during the three years prior to going back to his homeland, he missed Lizzie’s earlier enthusiastic involvement as a church volunteer or even just missed seeing her in her family’s pew.

Emma seems to have continued attending the Central Congregational Church and receiving counsel from Rev. Buck. In the interview she gave to a Boston Post reporter in 1913, Emma recounted her decision to leave Maplecroft several years previously, a decision possibly triggered by a party Lizzie had given for actress Nance O’Neil. Emma commented, “I did not go until conditions became absolutely unbearable. Then, before taking action, I consulted the Rev. Buck, who had for years been the family spiritual advisor. After carefully listening to my story he said it was imperative that I should make my home elsewhere.”

Apparently Emma continued to be friendly with whoever lived in Rev. Buck’s home after his death for Rebello records that she gave her 1913 interview from the parlor of what had been his home.

Rev. Edwin Augustus Buck died at his home in Fall River on March 9, 1903. The Central Congregational Church conducted funeral services for the minister who had served it so faithfully. He was buried in Fall River’s Oak Grove Cemetery, the same graveyard in which the remains of Andrew, Abby, Emma, and Lizzie Borden rest.

Lizzie’s teaching of a Chinese Sunday School student has sparked an interesting theory regarding the Borden murders. That theory is described in a footnote in Edmund Pearson’s Trial of Lizzie Borden. Pearson writes that, “the late James L. Ford . . . form[ed] a theory that the murders were committed by one of the defendant’s Oriental pupils as an act of devotion to his beloved teacher. Evidence that the deaths were caused by a hatchet—a favorite weapon in Chinese ‘tong wars’ in New York—may have influenced Mr. Ford.”

The people who have owned and run the businesses that occupied the Rock St. building since it ceased being a place of worship did not forget that it had once been Lizzie’s church. In 1993, plans were made to celebrate Lizzie’s acquittal on the premises. According to Rebello, a Fall River Herald News article stated, “The Central Congregational Complex announced plans to commemorate the acquittal of Lizzie Borden on June 20, 1993. Scheduled events include lectures, Victorian music, walking tours of the historic Highlands area and William Norfolk’s play, The Lights Are Warm and Coloured, based on Lizzie’s life after her acquittal.” He goes on to note the celebration was postponed.

Oddly, the former church on Rock was the venue for filming a rock video by the band Aerosmith in May 1993!

The building that housed the Central Congregational Church still stands. Like other Fall River streets, it was renumbered in 1896 and its street address is now 100 Rock St. Today it houses a cooking school called the International Institute of Culinary Arts. The main teaching facility is called the Abbey Grill, apparently not in homage to Abby Borden but because it still possesses the beautiful stained glass windows inherited from the building’s ecclesiastical past.

Fran Jensen, a representative of the International Institute of Culinary Arts, wrote in an email to this author, “We purchased the building from SAVE [Save Architecturally Valued Edifices] in 1997,” after it had been vacant for a number of years. She continued, “We invested 2 million dollars into it, to make it a restaurant, school and function hall.”

Lizzie Borden is known to have been a person with a taste for the finer things in life and would probably have approved of a culinary school and eatery set up in a proud and majestic building like the one that once housed her dearly loved, then sadly lost to her, Central Congregational Church.

Works cited

Burt, Frank H. The Trial of Lizzie A. Borden. Upon an indictment charging her with the murders of Abby Durfee Borden and Andrew Jackson Borden. Before the Superior Court for the County of Bristol. Presiding, C.J. Mason, J.J. Blodgett, and J.J. Dewey. Official stenographic report by Frank H. Burt. New Bedford, MA, 1893, 2 volumes; Orlando: PearTree Press, 2001).

Eliade, Mircea, ed. The Encyclopedia of Religion. NY: Macmillan, 1987.

Fenner, Henry M. History of Fall River. NY: F.T. Smiley Publishing Co., 1906.

Pearson, Edmund. Trial of Lizzie Borden. NY: Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1927, PDF Version, H.E. Widdows, Orlando, FL: PearTree Press, 2001.

Phillips, Arthur. The Phillips History of Fall River. Fall River, MA: Dover Press, 1944-1946.

Rebello, Leonard. Lizzie Borden Past and Present. Fall River, MA: Al-Zach Press, 1999.