by Mary Elizabeth Naugle

First published in January/February, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Imagine the headlines if a maniac with a hatchet offed a customer in an Abercrombie and Fitch at the Mall of America, then took out a second victim in the Food Court ninety minutes later. Apart from the shock and dismay the crime would provoke, two factors would make the story a standout: first, the sheer audacity of the crime, second, the fact that the killer, passed by dozens of window shoppers, could go unchallenged during the ninety minute interval. Far fetched as it sounds, this scenario is not all that far removed from the events of August 4, 1892. For the Borden murders not only took place in broad daylight, but also in a neighborhood that was a hive of activity. It is hard to appreciate just how much that hive was humming until you examine maps of the neighborhood and the number of witness statements from neighbors, shopkeepers, and laborers within a two-block radius. Many had a clear view of the house. None had seen anything out of the ordinary.

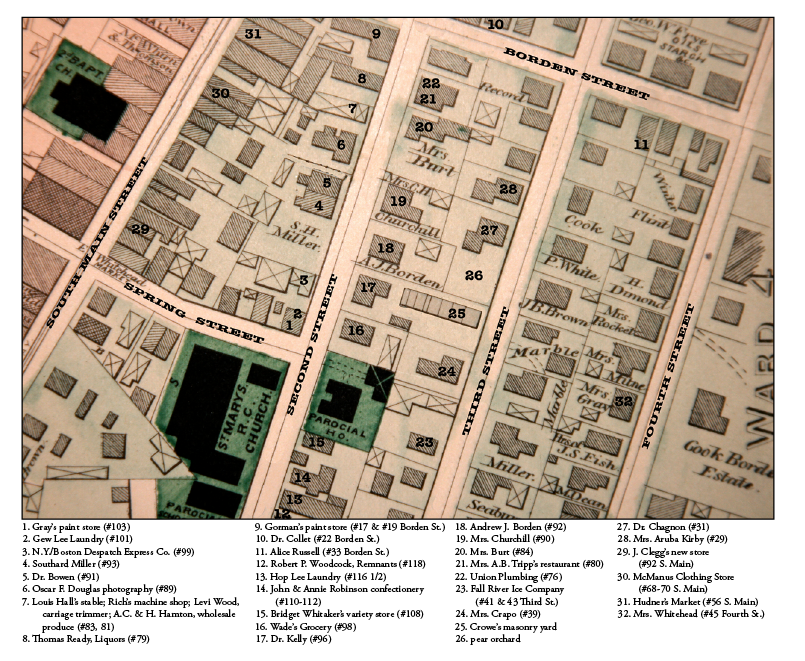

Significantly, Second Street, though residential in part, was a highly commercial street as well. Within the vicinity of the Borden home were an ice house, a masonry yard, four doctors’ offices, two groceries, a produce wholesaler, a remnant store, a variety store, a liquor store, two Chinese laundries, a photographer, an express company barn, a plumber, a dressmaker, a sign painter, two paint stores, a horse stable, a restaurant, a machine shop, two pharmacies, and a confectionery. In addition, the house was just north of St. Mary’s Church and its rectory. All these buildings were frequented by neighbors, peddlers, shoppers and shopkeepers going about their business in and out the various doors and up and down street on foot and by carriage. Right past the scene of two violent murders in a home that was practically perched on the sidewalk.

A close look at an 1890’s bird’s eye view of Ward 4 in Fall River and at Leonard Rebello’s Appendix D Map in his book Lizzie Borden Past & Present, reveals a series of buildings that rubbed elbows with each other. The Witness Statements, taken down by police investigators, further show that the shopkeepers stood in their doorways a good deal of the time—catching or shooting the breeze with the odd customer. Beginning with the west side of Second Street, St. Mary’s Church stood at the south corner of Second and Spring Streets. At the north corner was Gray’s paint store at Number 103 (#1 on the accompanying map); next, the Gew Lee Laundry at Number 101 (#2); and next to that, the barn for the N. Y./Boston Despatch Express Company at Number 99 (#3).

The Millers, whose maid with whom Bridget Sullivan was to stay afterward, were in the next house, Number 93 (#4). The house at Number 91 was Dr. Bowen’s (#5), a home business of the most unpredictable sort—in a day when doctors paid nothing but house calls, he might be fetched out or might return at any moment. Furthermore, Mrs. Dr. Bowen was watching anxiously for the arrival of their daughter, who was due home by train that morning. The upstairs boarder wasn’t talking. Next door, at Number 89, Oscar F. Douglas had set up a photography studio (#6), but he seems to have been in his darkroom that day, for we find no statement from him. Numbers 83 and 81 included Louis Hall’s stable—an outdoor business if there ever was one—Rich’s machine shop; Levi Wood, carriage trimmer; and A.C. & H. Hampton, wholesale produce (#7). Number 79 was the nemesis of the Young Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Thomas Ready, Liquors (#8).

At the intersection of Second and Borden there was Gorman’s paint store on the southwest corner at Numbers 17 and 19 Borden Street (#9); Dr. Collet, whose daughter Lucy figured prominently as witness at the Chagnon house, was on the north side of Borden Street at Number 22 (#10). On the corner, was Walter J. Brow, apothecary, at Number 62 Second Street. These businesses stood ready for those seeking maintenance for the home or body—the pharmacy all set for those wishing to postpone a trip to the doctor or to fill the doctors’ (any one of the four in the area) prescriptions. If the pharmaceuticals whetted customer appetites, the siren song and scent of Star Bakery wafted down from one block east. Diagonally across Borden Street from Dr. Collet’s house, and east of Third, was Alice Russell’s new address at Number 33 (#11).

On the southeast side of Second Street near Rodman, were Robert P. Woodcock, Remnants, at Number 118 (#12), the Hop Lee Laundry at Number 116 ½ (#13), John and Annie Robinson’s confectionery at Numbers 110-12 (#14), Bridget Whitaker’s variety store at Number 108 (#15), and St. Mary’s rectory across from the church at Number 104. North of the rectory was an orchard, Wade’s Grocery stood at Number 98 (#16), and the Dr. Kellys’ home and office were at Number 96 (#17). Although there is supposed to have been a full lot between Kellys’ and the infamous Borden home at Number 92 (#18), photos seem to show only a narrow distance between them. Next to the Bordens, of course, was Mrs. Churchill at Number 90 (#19), where two occupants (Mrs. Churchill and Mrs. Buffinton) and a visitor (Mrs. Gormley), were able to look out from a variety of prospects. Skipping the residence of Mrs. Burt at Number 84 (#20), who offered no testimony, we find Mrs. A.B. Tripp’s restaurant at Number 80 (#21), Charles Sawyer, sign painter at Number 78, and Union Plumbing next to that at Number 76 (#22).

Behind the St. Mary’s Rectory on Second Street was the Fall River Ice Company, Numbers 41 and 43 Third Street (#23), which did a brisk trade hauling ice for delivery that August day and had several men working—none having seen a thing (Statements 8). Next door was Mrs. Crapo and her girl at Number 39, who said they had heard no noise that morning, nor had they seen anyone go through the yard (#24); then Crowe’s masonry yard, where laborers worked outdoors all morning (#25). Next to Crowe’s was the one vacant lot behind the Borden home: a pear orchard, which might have provided cover for the culprit had it been more accessible (#26). However, a board fence, strung with barbed wire across the top, backed that orchard, directly behind the Bordens. Beside the orchard was the home of Dr. Chagnon at Number 31, who was out of town but had arranged for Lucy Collet to watch the home and take calls that morning (#27). The poor girl found herself locked out upon her arrival, though, so she minded the office from the piazza at the front of the Chagnon home, where she might have seen anyone coming from the southwest portion of the yard. The other side of the yard was covered by Mrs. Aruba Kirby at Number 29, who divided her time that morning between her kitchen, which looked out onto the Chagnon driveway south, and her sink room, where she had her back to that window (#28).

Once the alarm was raised, the police established the whereabouts and whenabouts of the potential witnesses and culprits. Inspectors were most concerned with observations made between 9:00, when Abby Borden was last seen, and 11:15 when the alarm was raised. They were flooded with statements. From early that morning to the discovery, men such as John Crowe, John Denny, and others were busy at the Crowe’s lot site (Statements 8). A suspicious man sighted on the fence and woodpile at the back of the Borden yard turned out to be Patrick McGowan, taking a break to eat some pears (Trial 1195). Although the barbed wire top would seem to have made the fence an unlikely spot for a snack, McGowan’s movements that morning were deemed sufficiently accounted for.

Initially, Lucy Collet claimed to have stood guard at Chagnon’s from 9:45 on (Statements 7); however, she revised her arrival time to 10:50, when under oath (Preliminary 229). That change means she could not have seen the arrival of a killer—only the departure and only if the killer escaped on the south side of the house. Aruba Kirby, however, who lived to the north of Chagnons, insisted that she saw and heard nothing from that way either, even though she was in the kitchen and sink room all morning (Statements 19). The houses flanking the Borden’s were likewise well covered. Mary, the Kelly maid, was working in the Kelly yard that morning, and Mrs. Kelly was observant enough to have noticed Andrew holding a small parcel and struggling with the front door about the time she left for a dentist’s appointment. She could not have witnessed an escape, but might have noticed suspicious entry (Statements 10).

Three women were at the Churchill house: Mrs. Gormley, a visitor, heard nothing out the open window (Statements 8); Mrs. Churchill, who was out but briefly to Hudner’s Market, which was located around the corner of Borden Street on South Main (#31), between 11:00 and 11:15 saw nothing unusual (Preliminary 127); and Mrs. Buffinton, mother of Mrs. Churchill, who was trundling a sick baby back and forth in the dining room and also noticed nothing (Statements 8-9). Across the street, Mark Chase claimed to have moved continuously between the Express stable where he worked and Wade’s Store (Statements 20). Mrs. Dr. Bowen was watching for her daughter from the parlor window facing Second Street. She decided to give it up at 10:55 (Statements 10). Farther up the block at 81, Louis Hall stood before his office “for some time before eleven o’clock.” He claimed to “generally observe whoever is on the street, and [was] most positive [he] would notice any suspicious character” (Statements 19).

In addition to the residents and workers thereabout, many passersby came forward to testify to the nothing they had seen and heard. Only three unusual sightings were reported. First, a man was reported by several people to have been looking for a driver to New Bedford between 2:30 and 3:30. The man, described as dark complected, dark suited, and walking with an obvious lean to the left, was first encountered at the corner of Pleasant and Eight Rod Way. Six witnesses came forward to give statements as to his impatience (so great that he kicked one man’s horse to make it go faster and offered up to ten dollars for the ride to New Bedford). The only problem is that no one noticed any blood, and no one had seen him near the Borden home (Statements 40-42).

The second suspicious person was reported by James Cunneen and proved to be yet a fifth doctor in the case, Dr. Handy. While driving up Second Street, Cunneen noticed Dr. Handy’s carriage pulled up opposite the Kelly yard. Cunneen said Handy turned “his head from right to left, and left to right. He seemed very nervous, and his strange actions caused me to look around to see what was the occasion of this; but I observed nothing” (Statements 19). The police appear not to have pressed Cunneen for a time. When questioned, Handy first claimed not to have stopped at all (Statements 19). Then, at the preliminary hearing, Handy admitted to stopping sometime between 10:20 and 10:40 in the spot described by Cunneen to observe yet a third shifty looking character. That man Handy described as “small,” with a “full face,” and “exceedingly pale.” Handy recalled the man’s suit as light colored, and said his attention was drawn by his actions: “vacillating or oscillating on the sidewalk” (Preliminary 390-2). Unfortunately, Handy’s man does not match descriptions of the impatient pilgrim to New Bedford. In the long run, the most disturbing of the three suspects is Dr. Handy himself, but no one seems to have pursued the matter.

There were two rather anti-climactic reports of a man lingering in front of the Borden home close to the crucial times. One came from Delia Manley who was with Sarah Hart when she saw a young man standing by the north gate of the house between 9:45 and 9:55. Unfortunately, beyond saying he was young, she could give no description of this loiterer, nor could she say that his behavior was at all remarkable (Preliminary 392-3). The other report came from Mark Chase from the Express barn. He claimed to have been across from Number 92 between 10:50 and 10:55, when he observed a high back buggy and man beside the tree in front of Mr. Borden’s fence (Trial 1361-1364). This was the full extent of his observation, however. No description, no bloody hatchet, no oscillations. The later statement also contradicts his original claim to have seen nothing untoward.

And these were the sentinels of Second Street.

Statements and testimony reveal a fluidity of movement on the block and a vagary of timing during the crucial period. Who could blame them? After all, the neighbors were not posted for sentry duty; they were simply going about business as usual, at work or home. Therefore, they had no reason to stay in one place for the morning, nor did they have a great deal of time to spend watching the neighbors. This fact could work both for and against the assassin. On the one hand, the killer had the advantage of being the only one to know there was something to look out for. The hatchet-handler could watch out for watchful eyes, even calculate whether being seen at some point in the morning might be to his or her advantage. Working against the killer was the fact that these neighbors defied planning. Their habits were irregular. The doctors could not be counted upon to come or go at any particular time. The stable hands, masons, and icemen would be moving back and forth upon their lots as needed, and they took their lunch in the open air. Customers might come or go, and shopkeepers frequently stepped out. Housewives moved about their homes, did their marketing up and down street, and cared for fretful babies, whose cries might mask the death throes of the victims but could not be relied upon to do so. Unlike a heist caper in a movie, this crime could not be planned around the obligingly regular habits of the potential witnesses. The movements of the neighborhood on this or any other day were random at best. The murders, whether done from within or without, were not the work of a criminal mastermind but the work of someone with incredibly dumb luck. Had the crimes been the invention of a mystery writer, Raymond Chandler would have dismissed the killer as “having God sit in his lap.”

Nevertheless, the Second Street sentinels did have one thing in common that worked in the culprit’s favor. They were all busy with their own lives. They were doing hard labor, drumming up business, seeking out bargains, fretting over a late train, changing a sick baby’s diaper, grudgingly sloshing water on dirty windows, wistfully dreaming of lemonade just out of reach behind a locked door, or even munching pears up in a loft. What they weren’t doing was guarding the odd couple next door, who were struck down even though they always kept their doors firmly locked.