by Denise Noe

First published in June/July, 2005, Volume 2, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

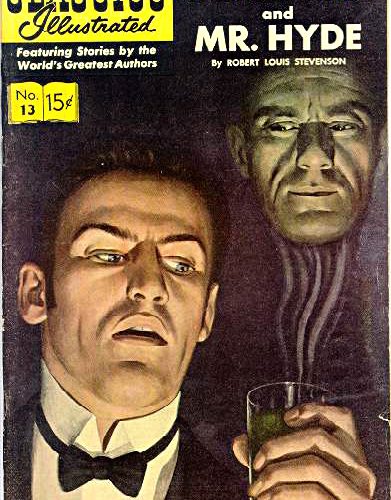

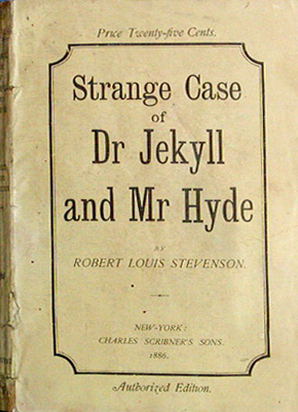

Published in 1886, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde has the force of a classic myth or fairy tale in the way it speaks to humanity’s deepest fears. The phrase “Jekyll-Hyde” has entered common parlance and is automatically understood.

It is not known if Lizzie Borden read this book. However, it is far from unreasonable to think she may have since, according to Len Rebello in Lizzie Borden: Past and Present, a friend described her as a “great reader” who read “all standard novels down to the popular stories of the day. Her father always had a good library.” She is reputed to have read Emerson and Carlyle, and a thrilling novel, with the impact of a horror story, may have also appealed to this Victorian Miss. We can be linked to Lizzie’s thoughts through what we read from that age.

It is not known if Lizzie Borden read this book. However, it is far from unreasonable to think she may have since, according to Len Rebello in Lizzie Borden: Past and Present, a friend described her as a “great reader” who read “all standard novels down to the popular stories of the day. Her father always had a good library.” She is reputed to have read Emerson and Carlyle, and a thrilling novel, with the impact of a horror story, may have also appealed to this Victorian Miss. We can be linked to Lizzie’s thoughts through what we read from that age.

Even as the story resonates cross-culturally and through the years, it could be seen as a tale that could only have originated in the milieu in which it was in fact written, the Victorian era, with its strong insistence on public propriety and rigid sexual repression. Robert Louis Stevenson claimed the idea for the novel came to him in a dream so it is not surprising that the story itself has a nightmarish quality.

The reader first learns of Hyde as a brutal man who deliberately walked right into and trampled over a 10-year-old girl. This Hyde has a friend and benefactor in a physician named Dr. Henry Jekyll who wrote a check to the child’s family so they would not press charges against his friend. The friendship between these two men is puzzling. Hyde is described as, “a fellow that nobody could have to do with, a really damnable man,” while Jekyll is “the very pink of the proprieties, celebrated too, and (what makes it worse) one of your fellows who do what they call good.” Not only is the “damnable” Hyde a bad man but also he is a man who looks the part. A character says, “There is something wrong with his appearance; something displeasing, something downright detestable” and that he “must be deformed somewhere.” However, the deformity is of a bizarre sort that escapes categorization since, “he gives a strong feeling of deformity, although I couldn’t specify the point. He’s an extraordinary-looking man, and yet I really can name nothing out of the way.”

What is the root of the friendship between Dr. Jekyll, a respected gentleman, and Hyde, a callous brute whom no other decent person but Jekyll “could have to do with”? A seeming clue appears with the information that Jekyll has not always been “the very pink of the proprieties” but “was wild when he was young.” Thus, it is speculated that Hyde might be blackmailing him with knowledge of a youthful transgression. A character in Mary Reilly, a contemporary movie inspired by this story, speculates that Hyde may be Jekyll’s out of wedlock son, a “wild oat” sown in his youth.

Indeed, while Hyde is frequently thought of as Jekyll’s evil twin, the novella itself often talks of a father-son relationship. Jekyll says that he has done scientific experiments that allow him to bring out the more primitive elements of his nature by transforming him into Hyde and speaks of both himself and Hyde in the third person and as if they are parent and child. We are told that “Jekyll had more than a father’s interest; Hyde had more than a son’s indifference.” The mature Jekyll, tempted but restrained by conscience, appears the quintessential middle-aged and responsible paterfamilias while Hyde seems like the paradigmatic rebellious and irresponsible youth, heedless of consequences and carelessly indulging his whims.

Much in the novel is heavily symbolic; perhaps most dramatically the name of Jekyll’s alter ego. “Hyde” suggests the forces of wickedness hidden within the civilized individual. It may also be suggestive of “hide” in the sense of the flesh and its desires.

Jekyll remarks on his own “undignified” yearnings and tells us that, when he was young, “the worst of my faults was a certain impatient gaiety of disposition” that he “found it hard to reconcile with my imperious desire to carry my head high.” Perhaps equally telling, Hyde has the “hairy hand” that was, in Victorian folk belief, thought to be the mark of the habitual masturbator.

In her forward to the University of Nebraska Press edition of the novel, Joyce Carol Oates wrote that she believes that Hyde’s trampling of a 10-year-old child suggests, to the extent a work published in the era could, a sex crime. “Much is made subsequently,” Oates pointed out, “of the girl’s ‘screaming’; and of the fact that money is paid to her family as recompense for her violation.”

The novel may be read as a warning against sexual repression and that is how Oates views it: “Had the Victorian ideal been less hypocritically ideal or had Dr. Jekyll been content with a less perfect public reputation his tragedy would not have occurred.” Dr. Jekyll may have turned himself into Hyde in order to take a pleasant wank, then unwittingly released horrendously destructive impulses.

The novel may be read as a warning against sexual repression and that is how Oates views it: “Had the Victorian ideal been less hypocritically ideal or had Dr. Jekyll been content with a less perfect public reputation his tragedy would not have occurred.” Dr. Jekyll may have turned himself into Hyde in order to take a pleasant wank, then unwittingly released horrendously destructive impulses.

However, the story could also be interpreted as a warning against sexual indulgence because surrendering to our fleshly desires inevitably leads us to wrong other people. Looking at sexual behavior from a specifically male viewpoint (since this story focuses on men), a man who casually indulges his appetites may become callous, if not cruel. The heterosexually inclined male, who has sex with “loose women” or female prostitutes, can cause much harm. Attracted by a wasp waist, he is absent when the belly rises, and does not give the pregnant woman either emotional or financial support at a time she badly needs both, nor is he around to help with the awesome demands of rearing a child. The works of Charles Dickens tell of the terrible fates suffered by orphans in Robert Louis Stevenson’s day. Whether heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual, a promiscuous man may both receive and spread sexually transmitted diseases. Syphilis was about as mortal of a threat in Victorian England as AIDS is in today’s world.

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde has much in common with two other classics of the Victorian period, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. Like Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde warns that our scientific knowledge and capabilities may outstrip our wisdom to put them to good use. Both can also be seen—as can the story of Adam’s rib—as fantasies in which men give birth. Jekyll wrote of his transformation into Hyde, “The most racking pangs succeeded: a grinding in the bones, deadly nausea, and a horror of the spirit that cannot be exceeded at the hour of birth or death.”

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde has much in common with two other classics of the Victorian period, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. Like Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde warns that our scientific knowledge and capabilities may outstrip our wisdom to put them to good use. Both can also be seen—as can the story of Adam’s rib—as fantasies in which men give birth. Jekyll wrote of his transformation into Hyde, “The most racking pangs succeeded: a grinding in the bones, deadly nausea, and a horror of the spirit that cannot be exceeded at the hour of birth or death.”

As Oates noted, the creature created by Dr. Frankenstein and that conjured up by Dr. Jekyll differ dramatically in size. “Unlike Frankenstein’s monster,” she wrote, “who is nearly twice the size of an average man, Jekyll’s monster is dwarfed.” The meaning here seems to be that evil is small, for to be wicked is to be much less than what human beings are capable of being. Like The Picture of Dorian Gray, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is about the tragic duality of human beings—the need to responsibly suppress and sublimate our most destructive impulses combined with the dangers of too rigorously repressing natural yearnings.

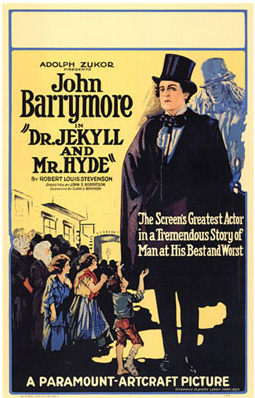

One gauge of the emotional resonance that this story has can be found in the extraordinary number of movies specifically based on The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The Internet Movie Database lists no less than eighteen movies titled Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. There are two more movies titled The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and two with “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” in the title (Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde Rock’n’Roll Musical). A 1920 silent movie version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde starred the legendary actor John Barrymore and was directed by John S. Robertson. The sets of the film are suitably antiquated and the atmosphere appropriately eerie so it can still be appreciated today, at least by those who are able to enjoy silent films.

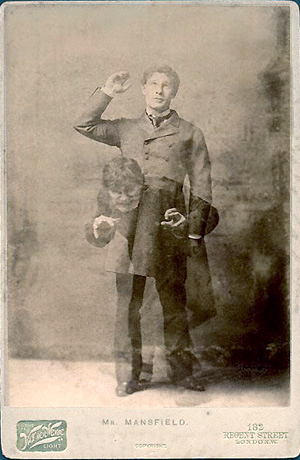

This motion picture, like others, embroiders quite a bit on the book. Stevenson’s novel was silent about any “respectable” love life for Jekyll and necessarily coy about any sexual indiscretions of his younger self or of Hyde. A saintly man who runs a hospital for the poor at his own expense, Barrymore’s Dr. Jekyll is shown as having two love interests, a classic “good girl” and equally classic “bad girl,” both based on characters first created in the 1887 stage play by T.R. Sullivan. Delicate-featured Martha Mansfield plays Millicent Carew, the virginal upper-class maiden. (It would be a breakthrough part for Mansfield but, sadly, her career would not last long. Four years later, she would be killed on the set of another movie. Her dress caught on fire from a carelessly tossed match and she died of severe burns.)

Dr. Jekyll is at a dinner party with the oily Sir George Carew (Brandon Hurst) who challenges this goody two-shoes. Appearing on the screen as Carew speaks are the words, “A man cannot control the savage in himself by denying its impulses. The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it.” Soon Carew leads the doctor to a music hall where he encounters temptation in the form of the sensuous singer and dancer Miss Gina (Nita Naldi). He resists but becomes obsessed with the idea of separating human nature so one side can indulge its baser appetites while the soul of the good side remains spotless. Barrymore’s transformation into Hyde is wonderfully creepy. It is accomplished with no special effects and little make-up but is largely a showcasing of this extraordinary actor’s ability to convey character change through manner and attitude.

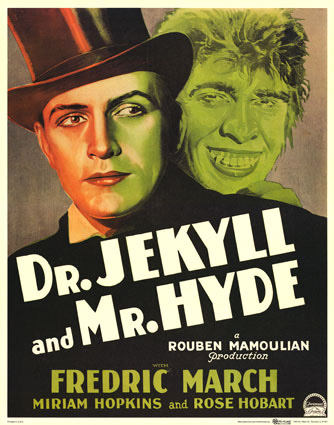

Among the best-known “talkie” versions of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is the movie released in 1931, directed by Rouben Mamoulian and starring Fredric March, Miriam Hopkins, and Rose Hobart.

Handsome in a clean, classically sculptured way, March had been known primarily as a comic actor before playing the title character(s) in Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Some at the studio objected to Mamoulian’s casting. The director countered, “I don’t want Hyde to be a monster. Hyde is not evil; he is the primitive, the animal in us, whereas Jekyll is a cultured man, representing the intellect. Hyde is the Neanderthal man, and March’s makeup was designed as such.” Indeed, when March turns into Hyde, he appears distinctly ape-like with hairy hands and a forehead made low by the growth of hair over it.

The role was a turning point for March who was not only taken far more seriously as an actor after it but also won the 1932 Oscar for Best Actor for his performance in the demanding dual role.

This Mamoulian movie depicts Jekyll (his name in the film is pronounced as “Gee-kul”) as an idealistic young doctor and scientific experimenter. He believes that people can conquer the evil in human nature by finding a way to chemically separate the two sides of that nature. Those around him dismiss such philosophical meanderings as silliness or, worse, a kind of blasphemy.

March’s Dr. Jekyll is in love with a proper, upper-class young lady named Muriel Carew (Rose Hobart). He encounters a lovely woman of the streets named Ivy (Miriam Hopkins). She has just been roughed up and the physician follows her to her home to examine her injuries. Tempted by Ivy’s charms, he leaves before it can get very far but the image of her shapely leg, fetchingly set off by a frilly garter and swinging by the side of her bed, lingers in his mind.

When Jekyll succeeds in separating his natures, the ugly, hairy, wicked Hyde seeks out Ivy and puts her up in an apartment. She dreads his visits in which sex is inevitably accompanied by violence of a pressured, rather than consensual, sort.

Even after so many decades, the 1931 film’s transformation scenes are dazzling. According to the Internet Movie Database, “The remarkable Jekyll-to-Hyde transition scenes in this film were accomplished by manipulating a series of filters in front of the camera lens, filters which alternately revealed and obscured portions of Fredric March’s Hyde makeup. During the first transformation scene, the accompanying noises on the soundtrack included portions of Bach, a gong being played backwards, painting on the track, and, reportedly, a recording of director Rouben Mamoulian’s own heart.”

This Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was remade a decade later. The 1941 version, directed by Victor Fleming, stars Spencer Tracy as Jekyll-Hyde, Lana Turner as his upper-class love interest Beatrix Emery, and Ingrid Bergman as barmaid-sex object Ivy Peterson. The Internet Movie Database says that, “The studio had originally cast Ingrid Bergmen in the Beatrix Emery role and Lana Turner in the Ivy Peterson role. Bergman felt the role of Ivy was more challenging and persuaded the producers to [let her] switch roles with Turner.”

Essentially a re-telling of the Mamoulian film, Tracy’s make-up is much more subtle and less ape-like than that of March. He never grows the hair on his hands that Victorians associated with sex-for-one. Rather, like Barrymore, Tracy relies primarily on changes in attitude and mannerism to suggest the transformation into pure evil.

In its depiction of Dr. Jekyll’s fantasies, the Fleming film is daringly kinky. In his mind’s eye, Jekyll sees Ivy being pulled out of bottle with a corkscrew and both Ivy and Beatrix harnessed to a carriage like horses while he enthusiastically whips them.

Some movies have brought a female spin to the Jekyll-Hyde story. The 1957 Daughter of Dr. Jekyll directed by Edgar G. Ulmer centered on a young woman named Janet Smith (Gloria Talbot) who inherits a country manor and discovers that she is the progeny of Dr. Jekyll. Bodies start turning up and the distraught Janet “Jekyll” wonders if she has unknowingly turned into “Hyde.”

Some movies have brought a female spin to the Jekyll-Hyde story. The 1957 Daughter of Dr. Jekyll directed by Edgar G. Ulmer centered on a young woman named Janet Smith (Gloria Talbot) who inherits a country manor and discovers that she is the progeny of Dr. Jekyll. Bodies start turning up and the distraught Janet “Jekyll” wonders if she has unknowingly turned into “Hyde.”

A Hammer film directed by Roy Ward Baker and released in 1971 was entitled Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde. The filmmaker did not try to have an actor or actress play both male and female; Ralph Bates played Dr. Jekyll and Martine Beswick played Sister Hyde. In this film, Dr. Jekyll is researching a drug that will cure many common ills and stumbles across a concoction that turns him into a beautiful but evil woman. Since female hormones are required for the formula, the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders are committed to obtain these.

The 1996 Mary Reilly was directed by Stephen Frears and based on a novel by Valerie Martin, which was, of course, in turn inspired by Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. It tells the story from the viewpoint of the title character that is one of Dr. Jekyll’s housemaids. Played by Julia Roberts, Mary Reilly is a wan, humble, and continuously nervous soul. The theme of the duality of human nature is introduced when she recalls her father who became cruelly abusive when drunk. John Malkovich puts in a suitably layered performance as the polite, subdued Dr. Jekyll and is flamboyant as the careless, cruel Hyde. In contrast to the novel, this Hyde appears larger and more robust than Dr. Jekyll. Glenn Close puts in an appearance as a garishly made-up and toughened madam.

Mary Reilly opened to decidedly mixed reviews. Beautifully atmospheric, it won praise for its foreboding foggy look but was faulted for a slow pace. Some viewers felt deprived by Roberts’ necessarily grim performance as Mary since her lovely face is never lit up by a smile. However, it is definitely worth a look as it does have good performances and communicates a strong sense of the perennial struggle between good and evil that is at the heart of this story.

The story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde has also inspired quite a bit of cinematic comedy. Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, directed by Charles Lamont, came out in 1953. Boris Karloff plays Jekyll-Hyde. The Nutty Professor (1963) stars Jerry Lewis as a nerdish, socially inept college instructor who discovers a formula that turns him into charismatic party animal Buddy Love. The multi-talented Lewis also directed the movie and co-wrote the script with Bill Richmond. The 1996 remake directed by Tom Shadyac stars Eddie Murphy as the grossly fat Professor Sherman Klump who transforms himself into the slim but obnoxious Buddy Love through a potion.

The story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde has also inspired quite a bit of cinematic comedy. Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, directed by Charles Lamont, came out in 1953. Boris Karloff plays Jekyll-Hyde. The Nutty Professor (1963) stars Jerry Lewis as a nerdish, socially inept college instructor who discovers a formula that turns him into charismatic party animal Buddy Love. The multi-talented Lewis also directed the movie and co-wrote the script with Bill Richmond. The 1996 remake directed by Tom Shadyac stars Eddie Murphy as the grossly fat Professor Sherman Klump who transforms himself into the slim but obnoxious Buddy Love through a potion.

The comedic Dr. Jekyll and Ms. Hyde (1995), directed by David Price, seems to borrow a leaf from Daughter of Dr. Jekyll and another leaf from Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde. Dr. Richard Jacks (Timothy Daly) discovers he is the great-grandson of Dr. Jekyll and determines to make a similarly revolutionary discovery. He creates a potion that turns him into a beautiful superwoman named Helen Hyde (Sean Young).

A fascination with Jekyll-Hyde themes permeates popular culture through stories of contrasting “good” and “bad” twins as well as the veritable epidemic of multiple personality disorder on TV shows and in movies.

Real-life stories of serial murderers and other villains often contrast a respectable “Jekyll” façade with the malefactor who was “Hyde”-ing from friends and family. Where applicable, news reports often dwell on the contrast between a heinous crime(s), proven or alleged, and the supposed perpetrator’s probity.

Certainly that is true about many articles on Lizzie Borden. As I pointed out in my essay published in the February/March 2004 issue of The Hatchet, “Do Good People Commit Atrocities? The Deepest Question Raised by the Borden Case,” Lizzie Borden was a person with a sterling reputation prior to August 4, 1892. Quoting directly from that article, “Lizzie Borden appears to have possessed good qualities in full measure, both the ‘cool’ virtues of modesty and chastity and the ‘warmer’ positive attributes of kindness, generosity, and caring.” In the years before the murders, she was very active in charitable groups. After the trial, when public charity work was closed to her because of social ostracism, she continued to treat those she knew with great kindness. David Kent in Forty Whacks quotes a woman who kept up their friendship after the trial as saying, “She delighted to help people and gave most generously of her means. She helped several young people to obtain a college education. Fond of good reading herself, she saw to it that many persons who enjoyed good books but could not afford them were well supplied with reading matter.”

Many people believe that Lizzie Borden brutally murdered her stepmother and father. If she was in fact the vicious murderer they think her to have been, she was the ultimate, real life Jekyll-Hyde.

Works Cited:

“Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” Internet Movie Database 5 April 2005. <http://imdb.com> (30 May 2005).

Rebello, Len. Lizzie Borden Past & Present. Fall River: Al-Zach Press, 1999.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990.