by Kat Koorey

First published in Spring, 2011, Volume 7, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

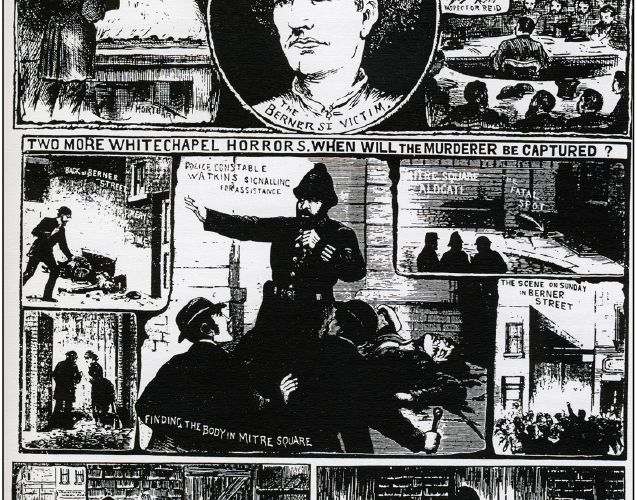

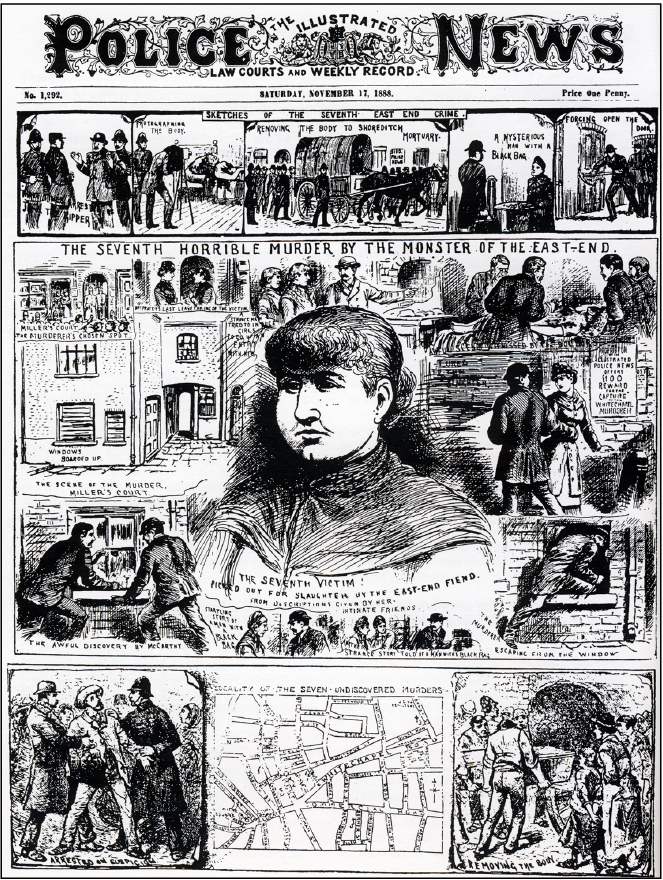

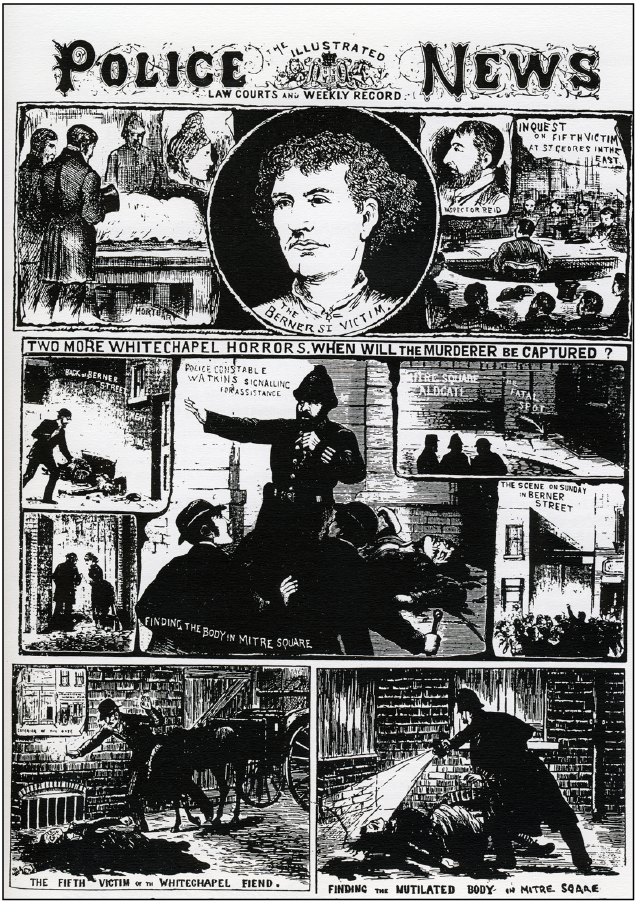

Everyone has heard of the name Jack the Ripper: that legendary hooligan who upset Victorian-era London in 1888 with his atrocious murders of at least five prostitutes in ten weeks. He struck by night, ripping these women open and handling their innards, displaying their bodies according to some kind of private ritual fantasy, and escaping without detection through the lurid, dark streets into history. This fiend’s name transcends generations; a world citizen who may not have heard of Lizzie Borden would still recognize the name of Jack the Ripper and know a little bit about those killings.

Movies, documentaries, websites, and countless books have been dedicated to the story—each emphasizing a particular suspect by providing “proof” or a unique clue to the identity of the miscreant, thus “closing” the cold case. Unfortunately, their views have been too narrow to accomplish anything other than contributing more pieces to the puzzle. Two separate authors, friends to one another, in the previous 25 years have proposed one name that would fit the case’s requirements, but, as usual, they don’t reach far enough. Their theory stays confined within self-imposed parameters.

This same suspect was recently resurrected in a 2009 television documentary. In using this suspect as a template, we can contemplate the bigger picture. While past researchers have been using a microscope, we will employ a sweeping searchlight.

We enter now the world of Jack the Ripper.

He is a hunter. Focused, senses alert, his veins are screaming—stealthily tracking, anticipating the attack.

His heart beats in his ear, drumming in matching rhythm with his prey.

They have not yet met, but their hearts are twined—not in sympathy—not in empathy, but as base animal creatures, one dying writhing miserably so that the other may feast, exalt, drain the life power, and discard the remains.

You eat the creature you kill to absorb them—so they only ever again exist as a shadow within you—their blood your blood—you own them.

He stretches his arms wide to the stars, leans back on muscled haunches.

He is released, and dominates once again. The night approves.

He smiles, with blood and entrails and gory fluids dripping from his gaping maw.

His eyes roll back, the whites show, eyelids flutter and he is back again, in control.

He looks normal.

He’s merely a red-meat eater—nothing lost, only gain.

It is his job, it is his passion. He is what he is made for.

He crawls, he skitters, he smells like fear and death—but not his fear and not his death.

How do you wash that away, deodorize, sanitize so there is no clue?

How do you have coffee in the morning, smoke a cigarette, read the newspaper?

He hates to put a lid on his beast and lock it away—but it is a choice of survival.

He revels in his secret life and he can’t wait to get to work again.

He knows in his marrow he is the only one fit to walk the planet and so he is alone.

He is the lust killer. Society breeds them in every generation. As sociopaths, they are not as unique as they like to feel, but this is the one who is deadly, who acts on his sadistic sexual fantasies. Some of this behavior is so deviant he cannot admit it, even to himself. He is anamorphic enough to defy understanding, and this naturally thwarts efforts to root him out, convict, and destroy him as a deadly alien visitor who threatens civilized society.

He grows in slums, suburbia, and salubrious backgrounds full of privilege. He is mixed up, messed up, and rabid. The face he shows his family, his employer, and the world, is his public mask—the face his victim sees, as the last glimpse of humanity on earth, is one of horror personified: a predator with bulging neck muscles, bared teeth, grunting enthusiasm, cold raging eyes, and a bitter heart of darkness.

There is a photo of Ted Bundy on the cover of the book Defending the Devil (Nelson, 1994), where the mask slipped, and his inner monster rose up, triumphant, off the leash, not to be denied. This image captures what true evil looks like as it descends to feed upon an innocent victim. He was a biter, therefore an eater, of beautiful woman-flesh, and it did not matter if it was alive or dead. A Bundy biter is like a Ripper—they both shiver in anticipation to get their hands inside their victim.

Some of the unfortunate early life experiences and unforeseen physical accidents that can contribute to the warping and colding of a male human heart have traits in common: a knock on the head; a puzzling complexity of inter-family relationships (when the grandmother is represented as the mother, and the mother is either unknown to the child or misrepresented as a sister); the perceived stigma of illegitimacy; the indulgence in violent sexual fantasies where the female becomes an object, not human at all, just a doll to be beaten and absorb the hurt and rage that is somehow tied to the act of sex; the preoccupation with sadism and violence; the sense of entitlement that allows the monster free expression adhering to no laws; and the freely chosen path of drug and alcohol abuse to lower the last and barely significant inhibition, with a concurrent over-indulgence or exposure to what society may consider pornography. These latter two stimulating factors are probably most important in the fantasy enactments that lead to murder and mayhem.

Bundy, in his live television interview, broadcast on the eve of his execution, boldly named alcohol and pornography as precipitating factors in his acting out. Of course he didn’t admit he had a choice as to whether he would indeed indulge in these activities; he must have known what such stimulation would lead to, having given in to this obsessive weakness over 100 times before (his own bragging estimate). There is not much soul-searching going on in these predator-humans—even as Bundy contemplated his own extinction within mere hours. He was grandstanding, he blamed society, he exhibited self-serving pity in an attempt to prove uniqueness (so as to be kept alive that doctors might study him); he had a weird capacity to justify within his mind what he had done, what death he had dealt others. This inability to fathom the consequences—that if he kills so must he be prepared to be killed—is forever puzzling to the representatives of the State intent on executing him, and the Society whose rule this is. He thought he was above the law. What makes him different in his own mind is an unanswered question only the dead can speak to after judgment.

The crimes of Jack the Ripper as a lust killer were the epitome of horror, and yet they only temporarily assuaged some terrible inner need in him to fill a personal black hole with female human blood. Women were chattel in most cultures from before written history, and socially sanctioned male dominance over millennia can breed sadism and a sense of superiority and contempt. Women were cattle: they might as well have moo-ed, so little did their language matter. They were only on the planet to be receptacles for male sexual gratification. But the overwhelming dichotomy, ever-present, the conundrum the man-mind could not grasp, was the reality that this woman was also their mother, the incubator of their children, and her contribution to the planet was crucial—so how can this conflict be resolved?

The average world citizen’s IQ is not much over 99 points, so the fact that the earth’s population is as civilized as it is is a wonder in itself. Women bear this with secret knowledge, and men make wars over huge populations attempting to establish boundaries, control, and dominance. And yet there are still also these few, these corrupt and licentious monsters, predators even outside of war’s rules of latitude, whose exploits and depredations have the ability to shock even the hangman.

Jack the Ripper Comes to America

A recent television documentary, titled “Jack the Ripper in America,” reintroduced a relatively unknown name as the culprit in the Ripper slayings. Host Ed Norris, a retired NYPD detective, ex-Police Commissioner, cold-case expert, and TV and radio star, appears in this role as the lead investigator: a sort of “Tom Colicchio of Crime.” He guides us through the process of discovery, evidence gathering, research, and the final conclusion drawn as to the identity of the Ripper. Viewers who are not aware of all the lesser-known suspects in these shocking Whitechapel killings may think he has found the solution, since he certainly exhibits a decided air of confidence when presenting his research as exciting new evidence, naming, as his choice, James Kelly.

The program begins in New York City where Norris walks the streets and describes what the area was like in 1891. Norris is indignant that the shocking murder and mutilation of a Miss Carrie Brown, who was found in a run-down brothel, where quick access to rooms cost a quarter and a trick cost fifty cents, remains unsolved on his streets. He stops at the modern-day spot, looks at the street sign where two roads converge, and resolves to pull the case folder and read it. By investigating the Carrie Brown crime, Norris, the viewer is led to believe, will eventually be led to the identity of Jack the Ripper.

This approach to the introduction of the Ripper material is intriguing. It subtly implies that Norris has embarked on a chivalrous crusade to solve the mystery of Brown’s slaughter and, by careful investigation, following accepted detective procedure, will uncover new information that will ultimately put to rest two NYC cold cases from 1891—while positing the conclusion that these killings were the work of Jack the Ripper.

A knowledgeable and committed Ripperologist would be unimpressed. Careful consideration of case literature proves that the Carrie Brown case cannot lead to the identity of the Ripper, but by following original source material, Jack the Ripper’s exploits can lead to Carrie Brown. Unfortunately, the second New York victim Norris has drawn into his investigation to bolster his case has spurious documentation. After showing a photo of her dead, drowned body, pulled from the East River on 7 August 1891, he quickly moves on. In truth, this other victim’s manner of death does not match any other, and she actually still remains unidentified.

Yet, the Carrie Brown case, because of its possible relationship to the Ripper murders, remains fascinating. Norris pores over the file at the New York State archives and invites an expert opinion by Dr. Jonathan Hayes on the “X” that had been carved on Carrie. Norris speculates it is a Roman numeral signifying a body count of ten—a number he arrives at by adding the five canonical victims of the Ripper together with his suspect James Kelly’s wife (as murder victim killed by Kelly), plus three more who are not usually attributed to the Whitechapel Ripper: Annie Millwood (25 February 1888), Ada Wilson (28 March 1888), and Martha Tabram (7 August 1888).

These additions are troublesome and tend to affect Norris’s credibility. It is interesting to note that the only source that compiles all of these names in one place is The Mammoth Book of Jack the Ripper (Jakubowski & Braund, 1999). Carrie Brown is listed on page 13 in the Chronology. James Kelly also appears as the subject in a major chapter contributed by James Tully, the author of Prisoner 1167 (1997). No other book before this one contains both this new suspected killer’s name and a new potential Ripper victim and, at 305 pages apart, they are not yet destined to meet in print. Philip Sugden, in 1994, in The Complete History of Jack the Ripper, broke the news item about the New York murder of Carrie Brown, but gives no reference to James Kelly. Tully, in 1997, devoted his whole book to his suspect James Kelly, who was apparently in New York around the time of that murder, but he makes no mention of Carrie Brown. Because of Norris’ obscure reference to Millwood and Wilson, it seems likely the documentary’s researchers used The Mammoth Book as a source.

A subsequent reference to Carrie Brown’s homicide is included in author Robert Graysmith’s 1999 Ripper book, The Bell Tower. She appears in a very short chapter entitled “Jack the Ripper comes to America.” Since the continuing title of Graysmith’s work is “The Case of Jack the Ripper Finally Solved…in San Francisco,” bringing Carrie Brown again into notice bolstered his case for an assault on America by the Ripper sometime after the London murders.

The next noteworthy revelation in Ripper literature was the discovery of, and investigation into, James Maybrick’s “diary,” which spawned multiple books—and the attention-deficit disorder that the reading public can experience due to multiple-theory bombardment—leaving Carrie Brown, and her momentary association with the name of suspect James Kelly, forgotten.

After the Maybrick sensation came Walter Sickert as the next big suspect (although not new), and Kelly was pretty much buried, until this November 2009 television documentary.

Granted, the online website discussion forum, Casebook Jack the Ripper, keeps all these theories and suspects organized, providing good material for researchers—but with a noticeable ten year gap in any interest in Kelly as a Ripper suspect, it is an unanswered question as to why the producers resurrected him to star as chief villain on The Discovery Channel.

Ed Norris talks to various experts in their fields. Sheila Kurtz analyzes the character traits of the writer of the “From Hell” letter. The fact that this horrifying message was written in blood and accompanied by a piece of human kidney makes any attempt at an objective analysis seem foolish, proving nothing. Steve Mancusi, a “NYP senior forensic artist,” is a most effective material expert who methodically de-ages a photograph of the elderly James Kelly, reportedly found by Norris. The resultant face matches 1888 witness statement descriptions, although the impact is considerably lessened when they go too far—adding a large mustache and a big floppy hat. The suspect now resembles anyone! It is ironic, as well, that the photograph of the aged Kelly is found on the cover of Tully’s book and one of him as a young man is readily found inside.

Norris visits what he deems to be significant sites, re-created scenes, and persons: a dungeon to experience true darkness, as some London streets might have seemed before electric lights—he steps back into a shadow and instantly becomes invisible which is a very stirring point; Smithfield Market to view butchers at work with bloody aprons, ostensibly to ascertain if someone covered in blood would be noticed on the street, in 1888, at night, during a get-away, and how common a sight it might be in that area; an upholsterer (James Kelly’s trade), who demonstrates the ripping action of the daily chore of stripping material and padding from a piece of furniture, with stress on the needful sharpness of the blade, which has valuable impact; and Broadmoor Lunatic Asylum, where Kelly’s file, photo, and “confession” were made available to him.

Kelly is described as prone to fits of rage, and “confesses” to “envy,” and “jealousy” and “malice,” possessing a hatred and obsession toward prostitutes, and being on the “warpath.” Norris sums him up as paranoid, delusional, and cunning enough to form a long-term plan of escape, which was successful. Kelly lists, in his post-escape narrative, the places to which he had traveled in his almost forty years as a fugitive, which Norris then uses in his investigation. Norris states that serial killers are well traveled, also making the point of how difficult and time consuming such extensive travel would have been in the late nineteenth century.

Three Ripper Suspects in America

Another source Norris uses is Dr. Thomas Bond’s contemporaneous original profile of the Ripper killer, which he deems “new” evidence. In this case it is true, as Bond’s writings had not been discovered until 1987, referenced in Donald Rumbelow’s fine offering of 1988, Jack the Ripper, The Complete Casebook. Norris uses Bond’s theories to eliminate two of his three likely suspects, settling on James Kelly.

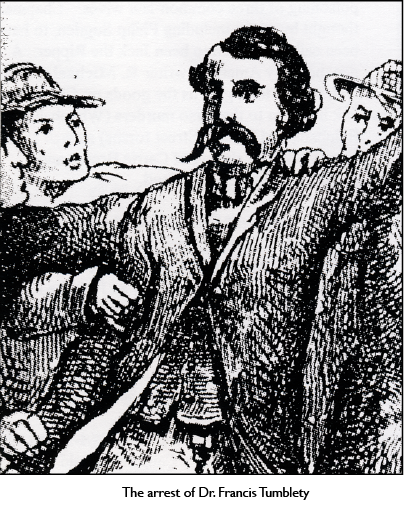

According to Jack the Ripper A to Z, by Begg, Fido, and Skinner (1991), Dr. (later Sir) Robert Anderson, the man in charge of the Ripper investigation since October 1888, brought Dr. Bond into the case, who made an examination of Mary Kelly and reported his findings to him. Anderson’s favorite suspect was a Polish Jew who had been captured and admitted to the insane asylum. Two names have been put forward of men who fit this description: Aaron Kosminski and “David Cohen.” Neither are considered by Norris and his Ripper expert Richard Jones; Jones’ three already established suspects, who had been considered insane and proven to have traveled to America (which meets Norris’ criteria) are Severin Klosowski, Francis Tumblety, and James Kelly.

Tumbelty’s name on that list is due to a coup accomplished by Stewart Evans in 1993. At that time, Evans acquired the “Littlechild Letter,” found in a batch of similar correspondence sold to him by a collector. Chief Inspector Littlechild, writing to a journalist in 1913 about the Ripper case, first mentions Canadian-born Frances Tumblety as a suspect. In fact, Evans, with Paul Gainey, based their 1995 investigative work The Lodger on Tumblety as Jack. That book is also published under the title Jack the Ripper, First American Serial Killer (1996).

Norris rightly dismisses Klosowski (aka George Chapman) because, as a wife-poisoner, he demonstrates a different M.O. from Jack. Tumbelty is considered too tall, too much of a character, and exhibited no violence towards women. In the Evans-Gainey book, Tumbelty is described as 5’10” at age seventeen, which would make him 55 years old in 1888 during those days of terror. Also, he was well known for “extremes in dress,” was always “pretentious” and “conspicuous,” with “titantian stature.” Additionally, he had a “very red face,” a “long flowing mustache,” wore fancy clothes, craved attention and notoriety, considered “handsome,” and had a reputation for being “eccentric and odd.” About the only personal attribute that might match Whitechapel murder witness descriptions is the fact that he sported a large moustache (192-7).

Referring to Evans-Gainey, again we find various descriptions from that time of the potential murderer where he averages between 30-38 years old, with a height most often given as 5’6” to 5’8”. Also, Tumblety, apparently, had more of a liking for young men rather than a demonstrable hatred toward women.

James Kelly as the Ripper

The remaining man from Norris’s short list, then, is James Kelly. Norris follows his pre-picked suspects’ exploits and gathers circumstantial evidence to fit him up as responsible for both the Whitechapel murders and the death of Carrie Brown, although it is unclear why this one homicide victim is highlighted in this television show and considered proof of Jack’s continuing work in the United States.

Norris then consults a map and plots the places where James Kelly claims in his “confession” to have visited: New Jersey, Galvaston and Dallas, Texas, and Los Angles and San Francisco, California. He finds similar murders there and makes the claim that James Kelly “puts himself in these cities.” There is an inference that Norris has found news items from these places, confirming continuing Ripper murders there, and now that Kelly is dead and taken his “secrets to the grave,” Norris’s case, though “circumstantial,” is “close to airtight.” He is satisfied he has solved the mystery of the identity of Jack the Ripper.

In The Complete History of Jack the Ripper (1994), Philip Sugden follows Ripper suspect Severin Klosowski’s criminal career. He is the first to reveal the Carrie Brown murder in New York City, naming her as a possible Ripper victim. Klosowski was Inspector Abberline’s personal favorite culprit, and he did have American connections and could possibly have been in the U.S. at the time of Carrie Brown’s homicide. It was the press who called up the recent nightmarish specter of Jack the Ripper with the headline “Choked, Then Mutilated, A Murder Like One of ‘Jack the Ripper’s’ Deeds’” (New York Times, 25 April 1891). Later in the article, though, the report states, “The police theory, however, is that ‘Jack’ is not in New York, but that an imitator, perhaps a crank, committed the murder.” This, before an autopsy was even performed!

The next day’s news coverage rightly made the distinction that “It would take a series of such crimes to establish the fact that the London ‘Jack the Ripper’ is in New York,” and by the following day the crime had become better known as the “East River Hotel Murder Case.” There was no further series of like murders identified, and the first suspect apprehended and detained, designated as “Frenchy #1,” held up through the whole investigation until he was finally taken to trial for murder in the second degree and sentenced to life imprisonment in July. Aamer Ben Ali served eleven years before the governor released him, due to a suspicion of planted evidence. Technically, that crime is unsolved.

The TV documentary’s theory is practical, potent, and well scripted—it’s just that the research is unoriginal: Dr. Bond’s 1888 suspect profile had previously been brought to light, Broadmoor’s files had already been breached, James Kelly had been a viable suspect since 1986 when John Morrison exposed his own theory in the newspapers, Carrie Brown had been tentatively linked to Jack the Ripper in a popular book in 1994, and other authors had plumbed world-wide news articles for ‘Ripper-like’ killings as early as 1928, deducing that he would need to find new killing fields away from the hot spot of Whitechapel, eventually landing in America.

We can be grateful to the program’s producers for the demonstration of a likely search for James Kelly that might link him to the Ripper. Although it is declared with confidence that the Ripper case is solved, author James Tully had already accomplished that. Their inclusion of Carrie Brown, in New York, to Jack’s list of victims is a creative steppingstone to bring him over the Pond and into the United States.

A Deeper Examination of the Suspect James Kelly

Profiling

John Douglas, known for his pioneering of serial offender predictive profiles, describes some indicative behaviors in his book Journey Into Darkness (with Mark Olshaker, 1997):

Most of them come from broken or dysfunctional homes. They’re generally products of some type of abuse, whether it’s physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, or a combination … By the time we see his first serious crime, he’s generally somewhere in his early to mid-twenties. He has low self-esteem and blames the rest of the world for his situation. He already has a bad track record, whether he’s been caught at it or not. It may be breaking and entering, it may have been rape or rape attempts … [has] a real problem with any type of authority … they believe they have been victims: they’ve been manipulated, they’ve been dominated, they’ve been controlled by others. But here, in this one situation fueled by fantasy, this inadequate, ineffectual nobody can manipulate and dominate a victim of his own; he can be in control … he’s finally calling the shots (36-37).

Describing Charles Manson, Douglas highlights the fact he was “born the illegitimate son of a sixteen-year-old prostitute who had grown up with a fanatically religious aunt and sadistic uncle until he began living on the streets at age 10” (37). Religionism plays a role (whether real or feigned). In a paranoid schizophrenic offender, he can believe he has the ability “to communicate with God. He might consider himself highly moral and whatever he does is because God has told him directly to do it … [has] hallucinations or delusions … religious delusions … [and likely to use] alcohol or drugs [to deal with stress]” (102). In a master manipulator, it would be difficult to determine whether this specific outlook was a form of reality to the offender or just another con.

In Jack the Ripper A to Z (1991), authors Begg, Fido, and Skinner include Dr. Bond’s deliberations on the psychology behind the criminality of Jack the Ripper. Writing in 1888, Bond listed two points specifically, hoping to describe the outlaw:

10. The murderer must have been a man of physical strength and of great coolness and daring … subject to periodical attacks of Homicidal and erotic mania … The murderer in external appearance is quite likely to be a quiet in-offensive looking man probably middle-aged and neatly and respectably dressed. I think he must be in the habit of wearing a cloak or overcoat or he could hardly have escaped notice in the streets if the blood on his hands or clothes were visible.

11. Assuming the murderer to be such a person … he would probably be solitary and eccentric in his habits, also he is most likely to be a man without a regular occupation, but with some small income or pension. He is possibly living among respectable persons who have some knowledge of his character and habits and who may have grounds for suspicions that he is not quite right in his mind at times (48-49).

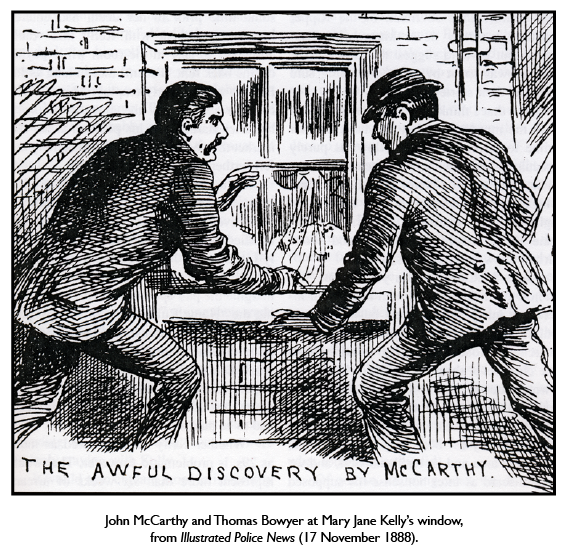

Bond’s conclusions, reached after examination of prior autopsy notes on the victims recovered from Buck’s Row, Hanbury Street, Berner Street, and Mitre Square, are considered “more speculative and, generally, less useful” (46) by the authors. His notations from his personal viewing of the remains of Mary Kelly from Dorset Street the day after her murder are described as having “limited intrinsic value, since he argues for instantaneous and silent killing in every case, despite the defense wounds on Mary Jane Kelly’s hands which he had observed. He accepts circumstantially impossible times of death for the cases on which he had read notes … [was in] conflict with Dr. Phillips … disputed Phillips … [and some of] his conclusions were not accepted” (49-50). Dr. Bond also changed his mind on cause of death of Rose Mylett. However, they did not criticize his offender profile. Author Tully, and Ed Norris after him, both seem to be excited and impressed by this 1888 document. They consider it remarkably innovative for the time period.

The History of James Kelly as Suspect Jack the Ripper

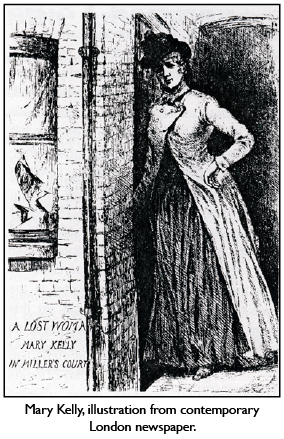

James Kelly was first introduced as a suspect to the public in 1986. One news item by Marcus Eliaso of the Associated Press, out of London, published in the Hendersonville, North Carolina Times-News of 5 December describes how John Morrison, a truck driver, aged 60, had recently erected a tombstone dedicated to the Ripper victim Mary Kelly in a Catholic cemetery in east London. Apparently Morrison had a crush on Mary Kelly, describing her as “the prettiest, the youngest. Everything about Mary Kelly was gorgeous. She was mixed up religiously, pregnant, in arrears with her rent. The poor little thing was the victim of circumstances.” Considered “an amateur sleuth” who compiled “files of correspondence with Scotland Yard, the Home Office and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher,” Morrison had collected a kind of “museum of drawings, maps and photographs” on the Ripper case.

The truth, he believes, is that Mary Kelly was murdered by one James Kelly, her former lover, who had escaped from a hospital for the criminally insane and gone looking for her in the East End, murdering prostitutes who happened to cross his path during his search and in the process earning the sobriquet of Jack the Ripper. … Morrison holds all rival theories in contempt. His ideas pour out in intricate detail, laced with quotations from long forgotten court cases and Home Office documents. He says it is on record that Kelly escaped from Broadmoor prison 65 days before the murders began, using a key fashioned from the wiring of a woman’s corset and making off with the staff’s weekly pay packet. He also says there is evidence that 39 years later he turned himself in claiming to be Jack the Ripper. Morrison claims the affair was hushed up because of the embarrassment that would be caused had it become known that Jack the Ripper had escaped from Broadmoor so easily.

John Morrison followed this news release in 1987 by self-publishing his own research as Jimmy Kelly’s Year of Ripper Murders 1888. (Note that his title implies one year of murders, even though Kelly traveled extensively after his escape.) Morrison, like many British authors on the subject, are notoriously insular and protective of their finite five victims in their few little acres of turf.

John Morrison followed this news release in 1987 by self-publishing his own research as Jimmy Kelly’s Year of Ripper Murders 1888. (Note that his title implies one year of murders, even though Kelly traveled extensively after his escape.) Morrison, like many British authors on the subject, are notoriously insular and protective of their finite five victims in their few little acres of turf.

Author Terence Sharkey capitalized on this new theory, including it at the end of his 1987 offering, Jack the Ripper, 100 Years of Investigation, in a chapter titled “Pick Your Ripper.” It was so new, one can almost hear the command “Hold the Press!” to allow for it’s addition—literally in the last 3 pages of his book. His version of Morrison’s theory adds that pregnant Mary Kelly “deserted him during his trial and fled to London from Liverpool in fear” (140). Although Sharkey’s treatment mentions the link between The Guinness World Records and Kelly’s escape from Broadmoor, he does not credit Morrison as the first to notice the listing that James Kelly had achieved the “longest escape from Broadmoor.”

Morrison’s imagination was stirred and he investigated the claim for four years, convinced James Kelly was the Ripper, but even his good friend Tully could not quite take him seriously. Morrison’s theory was next luridly paraphrased in Jack the Ripper A to Z, in 1991. It wasn’t until Tully decided to begin his own investigation, starting from scratch, that he became convinced Kelly was an extremely viable suspect.

Over time, certain earlier details fell away from the core story—Mary Kelly was pregnant and had either aborted or abandoned their child, giving James revenge and jealousy as motives; that authorities believed that since she was the primary victim the killings would stop, and therefore they no longer needed to pursue a killer and covered up the identity of the Ripper because of his status as an escaped lunatic; that this whole episode so embarrassed the government the original record of ‘longest escape from Broadmoor’ citation was removed from future editions of the “Records” book after c. 1985, with no explanation from the publishers; the claim that when Kelly turned himself in to Broadmoor in 1927 he said he was Jack the Ripper in order to be re-admitted, a story which seems to have no substance. Kelly did give a statement but it was mostly specious and vague. Any supposed family relationship rumored by Morrison to exist between the Ripper victim Kelly and the suspect James Kelly also was dropped from future speculations. The bare facts that remained surrounding the life, wife-killing, trial, incarceration, escape, and liberty of James Kelly are compelling enough on their own to stand as an interesting addition to Ripper lore.

James Kelly Fits the Profile

Born in 1860, James Kelly was raised in confusion about his origins: when he was fifteen he found out his mother died, whom he had never met; his grandmother Teresa had been passed off as his mother; he was illegitimate; on his mother’s side there was an insane cousin; he had had a stepfather who died before they met and who had no knowledge of Kelly’s existence; and he had been lied to by those closest to him. Soon, he was comfortable using three different names: Jim Kelly (his real mother’s maiden name), Jim Allan (his deceased stepfather’s last name), and John Miller (his real father’s real name). He was either suffering confusion over his identity or demonstrating an easy comfort in using an alias.

This was the Victorian Age, which made him the guilty scapegoat for his parent’s sin. He was left an inheritance in trust when he was to come of age at 25 in 1885, maybe as some compensation for his world being turned upside down, leaving him feeling somewhat entitled. His upbringing had been strictly religious, but the hypocrisy he now recognized sent him to the opposite extreme. By 1877, Teresa was dead and Kelly was worth about £26,600 in today’s money. With a rate of exchange figured at $2.50, in American dollars that would have been $86,5000, and only one trustee to convince each time he wanted a small advance. Kelly had become preoccupied with illicit sex and grew to believe women were whores, which might have been the outward manifestation of an innate schizophrenic paranoia.

He had trained as an upholsterer, as he had to work until old enough to enjoy the benefits of his inheritance. The knife seems to have become a comfortable and natural extension of his self, as he used it to attack his lawful wife in her home they shared with her parents. The 1883 marriage was a disaster and Kelly actually claimed his wife Sarah had given him a venereal disease, although he was still consorting with East End prostitutes. In a strange twist, he had married a woman named Sarah, making her Sarah Kelly, which was his mother’s name. Also, her mother’s first name was Sarah as well, although Sarah Brider. He ended that marriage by stabbing her in the neck and digging at her throat. She languished in hospital for three days, and after her deposition was taken, she died. During her dying, Kelly wrote his wife a letter, signing it “your loving and affectionate, but unfortunate husband, James Kelly” (Tully 37).

Kelly’s defense was “I must be mad” (Tully 33), and in July, the following month, he wrote his wife’s mother from jail, ending with “your forgiving but unfortunate son-in-law James Kelly” (Tully 39). She had lost a daughter to his murderous rage, yet Kelly was forgiving her for her witness statements—he continued to consider himself “unfortunate.”

There was an embarrassing trial the same year. Kelly had been evaluated over time by the assistant surgeon of the House of Detention, who testified there was no sign of insanity, although Kelly complained of misery and suffering due to pains in his head and had acted under an irresistible impulse. He was judged guilty with mercy recommended by his jury. Kelly claimed that during the stabbing “he was out of his mind, and he was sorry for it. He prayed God to forgive him, and felt sure that He had already forgiven him. For that reason he felt that he should like to live in order that he might serve God” (London Times, 2 August 1883).

The judge disagreed, ordered his death and, very shortly before sentence could be carried out, under a new government policy anticipating the new law about to be passed, an inquiry was made as to Kelly’s mental stability. The finding was one of “defective mental capacity” (Tully 50), and thus Kelly was admitted to Broadmoor Asylum, 7 August 1883, believing it was Divine Intervention.

He was justified, he was jealous, he was paranoid; it was rage against a woman who would not submit to his control. He was frustrated and stabbed her in rage. He considered himself innocent. It was someone else’s fault. He was “unfortunate” to find himself driven to the edge and having to defend his position.

James Kelly as wife-killer

Well, of course the blade used as a weapon to stab and tear a woman’s throat has a psycho-sexual symbolism and would be very gratifying and hard to relinquish once it had been employed in that capacity—a familiar trade tool—something always to hand—an extension of self utilized in a most satisfying way—ridding oneself of a burdensome shrewish wife which was his right—intimate and personal and oh so close up—you can breathe her fear and overpower her struggles—dominate—kind of like sex—and with a woman’s blood spilled all over his hands in a justifiable act—she made him do it—he warned her before—he’s hooked for life he and his knife—an exciting addiction. Once he’s committed to the asylum he’s not going to forget that power rush of settling a score, of setting things right—of taking his own—he’s going to have to escape. But he has patience because his bodily needs are cared for and he has time to settle his mind and there is excitement just in planning, now.

The mother-in-law Sarah stuck by him for years, maybe harboring expectations of all that lovely lucre her murderous son-in-law could not spend once he reached age 25 in Broadmoor. She might as well be compensated for the death of her daughter, who would have been Kelly’s natural heir anyway, and felt she was as deserving of that money as anyone, since the bequest was from the distant dead John Allan. How different the future would have been for both families if “unfortunate” James had had personal control of over $80,000 prior to 1883. A Trust can be proof one is not trusted. It is manipulation from beyond the grave and, in Kelly’s case, by those who had lied to him, those he had trusted.

As he grew, there were ten years where he was controlled by others making decisions for him about his life: that he would leave school and learn the upholstery trade by apprenticeship; that he would leave that and go to the Academy and learn clerking and bookkeeping; that he would go to work for a pawnbroker; and it was decided for him where he would live. By late 1878, he was showing signs of instability, had periodic rages, and became obsessed with moving away from Liverpool to start fresh in London where no one knew him and where he might re-invent himself. He was advanced money from his trust and tried to break into the London upholstery trade where the competition for work was huge, settling in an area on the outskirts of the East End. His job search would take him all over Spitalfields, Whitechapel, and Shoreditch, and he necessarily learned the interior routes through the alleyways, byways, and mazes of these areas.

Port city, pubs, multinationals, strange languages, noise, horse traffic, market stalls, blind alleys, dirt and debris, peculiar and nasty aromas, music, criminals and cons and pickpockets and prostitutes, fights, shouting, cursing and drinking, life lived outside in the open on the streets, urinating, furtive coupling, babies born, and folks dying. Sure he’d seen some things in Liverpool, but not on this scale.

And Kelly had some money to indulge his fancy and two friends to introduce him to the low life. Eventually, he moved into the East End to be closer to work and for the cheaper lodging.

Apparently, around 1879 he left London for Brighton and later served on an American Man-o-War, according to Dr. Treadwell at Clerkenwell Prison, where Kelly was stationed awaiting his trial. Back in London by Christmas 1881, and now 21 years old, he met Sarah Brider (the daughter) and moved into her home while pursuing her to marry him—a real home with an intact family already in place—and at first they welcomed him. Being in close proximity to his Sarah was frustrating him, as by now he was used to having his needs met on command by prostitutes and Sarah would not give in. She was in a bad position because he was pushing her for sex outside marriage but if she gave in he would judge her as like the whores on the street. She did give in and it was a disaster—neither of them knowing about love and affection and how sweetly bodies can fit together. There was guilt and recriminations: Kelly accused his Sarah of being less than a woman, of malformation, of something needing a doctor’s consultation, as well as striking out verbally at her mother as being her accomplice in this subterfuge.

Kelly degenerated into depression. He was acting erratically and finally admitted to himself he had contracted a venereal disease, which he tried to treat himself. He had lost his job and yet he and Sarah married anyway in June 1883. By the end of the month, Sarah was viciously attacked in the bedroom by his hand, his knife, his paranoia, his hatred of women, his diseased mind. Thus began his odyssey through the British justice system, which leaves records like breadcrumbs: jail, trial, sentence, evaluation, reprieve from death sentence, and admitted to the asylum under Her Majesty’s pleasure 1883. Still yet not of age to inherit his legacy, he was now a convicted felon, a mentally unbalanced wife-murderer.

His destiny to fail seems to have been latently lurking in his genes, complicated by his haphazard upbringing and lack of nurture from a mother he never even met and who essentially gave him away. Upon the revelation of these lies at the worst possible age of fifteen, he was spun into chaos when faced with these major life blows, with no experience or ability to handle them. His circuits eventually overloaded and he had begun to show the evidence of the symptoms of paranoid schizophrenia. His subsequent unpredictable behavior seems to prove this—his life decisions ever after were confused, irresponsible, and flawed. What is amazing was that he somehow managed to get through his life, perfect a trade he could fall back on during his restless and nomadic periods, travel the world and care for himself despite his handicap, and reach the ripe old age of 67 before giving up and returning to Broadmoor a physical and mental wreck in 1927.

The stories surrounding Kelly’s surrender to Broadmoor differ. Some say he claimed to be Jack the Ripper in order to be readmitted. He had been gone so long the institution had released him from their responsibility, formerly discharging him as a patient in 1907. In order for him to be not only accepted back but cared for in his final few years through his decline and death, there had to be a review and an official determination of his status—Broadmoor does not just take in old lunatics who show up knocking on the front door. A main requirement was that he tell his story, and Kelly had just enough cunning left to concoct one that would get him in without incriminating himself. He would want to make it interesting because he was in the spotlight again and craved that kind of attention, now that his hands were clean, but was careful about any criminal admissions. That is why a purported statement that he claimed to be the Ripper just doesn’t fit with Kelly’s personality, motives, or modus operandi.

But Kelly would want to seem heroic, mythical, and adventuresome. He described his travels through France, England, back and forth to America, all over the United States, and parts of Canada, by ship, by foot, and by rail. He had evaded capture through help of friends who he claimed did not know about his “trouble,” and loaned him money. He showed he was too clever for the establishment to catch him, even when he was living right under their noses, within a few miles of Broadmoor itself, at various times in his existence on the loose. He appeared grandiose while belittling the system and the authorities by relating how he turned himself in two times in other countries only to again disappear. He was careful not to admit much at all in the way of criminal activity—just your everyday escaped lunatic confession that would feed his need to manipulate, achieve re-admission, and leave him some mystery and cache that he could trade on in future with his fellow inmates—a typical con.

Any sociopath could pull this off, but the fact was that he was aging rapidly now that he no longer had to take care of himself, now that the stresses of daily survival issues were removed from his mind, now that he was irritable and deaf. It was amazing that he could even be coherent, let alone disciplined, and careful not to admit to anything other than to the initial murder of his wife, which was the original complaint against him. His statement has often been carelessly referred to as a “confession” by subsequent authors—a term implying that he made admission to be Jack the Ripper. John Morrison was the one who contributed to this legend, but it is not more than speculation now.

Tully stresses “Kelly was never precise whenever there was a possibility of incriminating himself or others,” and “the only information which we have comes from Kelly himself” (73), further describing the events as “Kelly’s authorized version” (70). Tully complains, “he was to be even more secretive about this particular period of his life”, i.e. the first half of 1888 (74).

His mental state deteriorated and he complained of being “dosed in order to make him an idiot” (93). He made feeble attempts to leave the facility, but as his health declined, so did his ability to even imagine the climb over a now-impenetrable sixteen-foot wall—the wall he had gone over in January, 1888, had been bolstered by ten more feet in 1892.

Tully makes especial note that upon Kelly’s death, 17 September 1929 of double pneumonia, “he had taken his secrets with him, most notably the details of what he did and where he lived in 1888/9, the years in which … London was terrorized by Jack the Ripper” (94).

Kelly did devolve into madness upon his re-entry to Broadmoor. What would have motivated him, though, to wander the world in his condition? Experts say paranoid schizophrenia is an illness that prevents the person from knowing they have it—but Kelly must have so valued his freedom that he was willing to fight for it, work for it, and even steal it from Her Majesty (as the Institution represents her). It would have been easier to just capitulate and be cared for by interns rather than chance an escape and try his luck at solitary survival in the vastness of world civilizations. So what was his drive? He must have been an opportunist, a salesman, and very clever. If he had a need to kill, which he knew he could not satisfy in Broadmoor, it might be the catalyst to propel him through the life he chose on the run. Ted Bundy did that, always looking to escape custody, preying on more victims in a sort of wild gluttony, while knowing his days of freedom were numbered once the system had his name and description. Authorities were convinced after Kelly’s trial that he was mentally ill and committed him. He was likely an excellent actor. Upon his return 39 years later he again was assessed as mentally unfit in order to be re-admitted. How had he survived? Anyway, by May 1928, he was “delusional and mentally enfeebled” (Tully 93); by December, his physical health had degenerated, and he was exhibiting paranoia and senility. But, by 1929, he was again plotting to escape! He died that same year.

James Kelly is a marvelous suspect, a wonderful find by Morrison, and an inspired choice for a Ripper documentary thanks to Tully’s years of investigation into his life, providing welcome documentation. However, through his own statement, we are only privy to what James Kelly wanted us to know, and it is self-serving, not very informative, and tends to become muddled when we get to the good parts. Killers are liars and serial killers are serial liars. Where there is mystery there will be speculation, but his statement contains no proof Kelly admitted to, nor ever killed, anyone anywhere other than his wife Sarah. We are relying on his words, but he was judged unsound. Also, the only times it can be established that he was where he says he was are when he came in from the cold to authorities in New Orleans in 1896 and in Vancouver, Canada in 1901. There were three murders in Essex, England, in 1893, when James Kelly was thought to be back in that country, and there was the Carrie Brown homicide in New York, when he was in the States, but attempting to pin any of these, or any other world-wide Ripper-style murders on little James Kelly from Lancashire is a doomed endeavor. The culprit could as easily have been Jacques, Hans, or even Jose the Ripper.

Jacques the Ripper?

At the time of Jack the Ripper’s hey-day, there were probably more than fifty like him in the world, if modern forensic profile experts are correct in their estimations. Which crimes are elevated into social consciousness, becoming infamous and notorious, is a result of diligent media reporting by the press in a highly civilized culture. Letters to the newspapers bragging about the killings were received, which added fuel to the outraged fervour of the British Empire at the time. Some say the press invented the correspondence to feed the fever and that a journalist was originally responsible for the appellation ‘Jack the Ripper.’ The name evoked such fascination that even captured killers of that era, such as Dr. Cream (1850-1892) and Frederick Deeming (1853-1892), allegedly confessed to be the Ripper to add to their own notoriety.

According to the Ashburton Guardian of 22 February 1889, prior to the Whitechapel murders, there had been on the loose in Russia a “lunatic … whose homicidal mania was directed against the very class from which ‘Jack the Ripper’s’ victims are selected, and who it was stated had eluded capture in his own country. It begins to look exceedingly likely that this Russian maniac reached London and there followed his evil bent.” The reporter theorizes the culprit then escaped to the Americas, “pursuing a similar bloodstained career” in the West Indies and “neighboring countries, where precisely similar crimes are now recorded.” The Ripper killings stopped in London in November 1888, but in December, the very next month, “four negresses were killed in Jamaica. This was followed by news from Nicaragua where six similar atrocities were committed in January.” The last Jamaican victim was found with a note conveniently attached to the body, with the words “Jack the Ripper” written there.

This report ties these types of crimes together globally and evinces the bigger picture, giving scale, scope, and context to a major trend of terror. The horrific depredations perpetrated upon those women of the East End of London were only a few in a series of exterminations around the world. It was the London press who whipped up the frenzy with their lurid and graphic reportage. It was really just a few months of a killer plague that merely passed through England— only to gather strength and fuel for future and further conquests in other countries and accumulating unfortunate female souls and body parts in some kind of evil and sadistic gluttony—mere glimpses of which left the newspaper-reading public aghast and terrified for a time.

The New York Sun, 7 February, 1889, published more detailed news of the Nicraguan women who were butchered at an alarming rate that past January, 1889—six victims in ten days:

The people have been greatly aroused by six of the most atrocious murders ever committed within the limits of this city. The murderer or murderers have vanished as quickly as ‘Jack the Ripper,’ and no traces have been left for identification. All of the victims were women and the character of those who met their fate at the hands of the London murderer. Like those women of Whitechapel, they were women who had sunk to the lowest degradations of their calling. They have been found murdered just as mysteriously, and the evidences point to almost identical methods. They were found butchered out of all recognition. Even their faces were most horribly slashed, and in the cases of all the others their persons were frightfully disfigured. There is no doubt that a sharp instrument violently but dexterously (sic) and was the weapon sent the poor creatures out of the world. Like ‘Jack the Ripper’s’ victims, they have been found in out-of-the-way places, three of them in the suburbs of the town and the others in dark alleys and corners. Two of the victims were found with gaudy jewellery (sic), and from this it is urged that the mysterious murderer had not committed the crimes for robbery. In the cases of the other four a few coins were found on the persons, representing no doubt the prospective consideration for the murderer or murderers. All of the victims were in the last stages of shabbiness and besottedness. In fact, in almost every detail the crimes and the characteristics are identical with the Whitechapel horrors. All of the murders occurred in less than ten days, and as yet the perpetrator or perpetrators have not been apprehended. Every effort is now being made to bring him or them to justice. The authorities have been stimulated in their efforts by the statement that seems to be generally accepted, that ‘Jack the Ripper’ must have emigrated to Central America and selected this city for his temporary abode.

Author’s Evans and Gainey (Jack the Ripper: First American Serial Killer) tell of an early author on the case, Guy Logan, who exposes the Jamaican and Nicaraguan murders in his book Masters of Crime. They quote Logan, writing in 1928:

I think it probable that the Whitechapel fiend, finding London at last too hot to hold him, deprived of the opportunities for his blood debauches, did betake himself abroad, and that he went to America. Further, I think it likely that he had come from the States in the first place (230).

Although Logan calls these series of crimes “multiple murder,” he is describing a traveling serial killer, only forty years after the London slayings wound down, and he wrote this, conceivably, within the killer or killers’ own lifetime!

A study of the life story of suspect James Kelly provides a liberating factor and it opens the Ripper case up to further possibilities—that the Ripper did travel, as serial killers are wont to do. He had crawled out of the dark scummy pit of his own fantasies in another country altogether, killing and causing mayhem there, escaped into the teeming sick belly of the East End of London, ripping it open and exposing her entrails, retreating this time to a warmer clime as winter hoved into England, and perpetrated more atrocities on defenseless female victims, playing god and demon in some sun-drenched party town in Central America like the devil on holiday.

A World-Wide View: The Ripper in Context

Further original research reveals a cursory collection of twenty-six news items of like crimes from around the world, all claiming relationship to London’s Jack the Ripper. England may have named him, but up until that time he had been at work anonymously, and probably continues to this day: some kind of evil vampire who has seemingly passed on his cruel disease to generations from the beginnings of time to the end of time.

Otego Witness 16 November 1888

(By the Daily News American Correspondent)

Not many months ago a series of remarkably brutal murders of women occurred in Texas, the victims being chiefly Negro women. The crimes were characterized by the same brutal methods as those of the Whitechapel murders. The theory has been suggested the perpetrator of the latter may be the Texas criminal, who was never discovered. A leading Southern newspaper thus puts the argument: -‘in our recent annals of crime there has been no other man capable of committing such deeds. The mysterious crimes in Texas have ceased. They have just commenced in London. Is the man from Texas at the bottom of them all? If he is the monster or lunatic he may be expected to appear anywhere. The fact that he is no longer at work in Texas argues his presence somewhere else. His peculiar line of work was executed in precisely the same manner as is now going on in London. Why should he not be there? The more one thinks of it the more irresistible becomes the conviction that he is the man from Texas. In these days of steam and cheap travel distance is nothing. The man who would kill a dozen women in Texas would not mind the inconvenience of a trip across the water, and once there he would not have any scruples about killing more women. The superintendent of the New York police admits the possibility of this theory being correct, but he does not think it probable.’

Fielding Star (Manawatu), 20 December 1890

Eight Murders Committed

(Per Press Association)

Mexico, December 19.

An American ‘Jack the Ripper,’ who has commenced his horrible work in this city, has already committed 8 murders.

The Colonist, 6 May 1892

Washington, May 4.

Another body of a woman, mutilated in the same way as Jack the Ripper’s victims, has been found in Chicago. This is the second within a short period.

Poverty Bay Herald, 22 April 1893

Is He Jack The Ripper?

A woman was ripped in New York on the night of the 19th of March, by a knife which was left sticking in the wound. The knife was traced to Frank Castellano, an Italian barber, whose record has been under police searchlight. There are circumstances connected with the case that incline the police to believe that Castellano is none other than the mysterious ‘Jack the Ripper.’

Otago Witness, 19 October 1893

Four women were murdered in the ‘Jack the Ripper’ style in Ostburg, an island of Cadizan, in the four days preceding September 4. No arrests have been made.

Star, 13 October 1899

Two murders, similar to those committed by Jack the Ripper in England, are reported from Linz, in Austria.

Star (Canterbury), 22 February 1902

An American Imitator.

United Press Association—By Electric Telegraph—Copyright.

(Received Feb. 22, 10.40 a.m.)

New York, Feb 21.

Eight murders of girls, after the methods practiced by ‘Jack the Ripper,’ have been committed in San Francisco.

The research into James Kelly as Jack the Ripper does demonstrate that the five London killings of the autumn of 1888 have been taken completely out of context from the world-view of similar contemporary atrocities. The question then arises as to why were only England’s victims made infamous? Why when we think Ripper do we only see the flash of poor Catherine Eddows’ face etched in light, like a reporter’s flashbulb, illuminating, for a moment, her post-autopsy stitches, like the bride of Frankenstein’s monster? Russia, Texas, Jamaica, Nicaragua, Mexico, Chicago, Australia, Austria, Essex, England, Cadizan, and Amsterdam all had their Rippers within the same decade. Why was only London in the world’s spotlight that autumn? Why are there dozens of books and several movies based on just these five ‘canonical’ victims: Mary Kelly, Catherine Eddows, Liz Stride, Polly Nichols, and Annie Chapman? We don’t even know the names of the unfortunates in these other countries, or even much detail—only these five are accepted in the legend of the Ripper’s exploits. The total victim count of Ripper-like murders from all the citations next listed here is 94, not including lone Carrie Brown in New York City. And yet scholars still argue whether to include Martha Tabram or Frances Coles in the elite restricted list.

There was always the question as to why these killings started here in London, in this particular place, and seemingly ended here, in this place and time. These crimes were held to be a political and sociological scandal of such magnitude that they actually reflected upon the state of the Monarchy, compelling the Queen to comment. Since that time, hundreds of hours of research and investigation has been done to qualify a Britisher as the culprit. Upon an examination of the story of the life of James Kelly, we find the whole world was open to the likes of such a degenerate killer as London’s ‘Jack.’ He was not a five-victim kind of guy, who then conveniently jumped into the Thames, committing suicide before the year was over. Obviously the murders stopped in England because ‘Jack’ took his blood-thirst on the road—a Victorian globetrotter when long-distance travel was not quick or easy. Killing women and then catching a train might have become his life’s work, a mode of existence.

As a typically modern phenomena, this traveling serial killer would probably have to have a tidy income to fund his lifestyle, and contribute to a clean and organized appearance; he would have a natural cunning and the ability to take care of himself in any country in the world. He couldn’t look like a monster by day, nor could he be actively insane or noticeably degenerate. He would have to have a sound-enough mind to plan and choose to do what he did, to get away uncaught, and to remain unsuspected. Consider that there also could have been several Ripper-like murderers working worldwide, which expert profilers claim is possible at any given time in any country. As John Douglas would admit, man’s inhumanity to woman crosses all time-zones, borders, and races throughout the history of the species.

Again, because of a study of the suspect James Kelly, we can see that London’s victims weren’t special, but that it was the press coverage that made them so. That it created it’s own phenomenon is worth further study: the role journalism plays in making any crime into a super-crime by concentrating vast media attention on to a particular story of human interest, like focusing a microscope under a bright light source and then describing the sickening undulations of an unknown organism caught in the magnified glare.

If these Whitechapel atrocities were an isolated series of murders specific to this time and place, beginning and ending there, then some of the historical suspect names proposed as candidates for Jack the Ripper will always be worth further investigation. The mystery is compelling and provocative when placed in 1888 East End Victorian London pea-soup foggy nights and sputtering gaslight murky darkness where a particular kind of evil lurked on silent watch with a flash of a knife. But if these killings were a set of crimes taken out of context of multiple similar crimes in other countries in the same decade, the fascination seems diluted and diffused, like a spotlight when it is spread over a wider area. The culprit becomes like a shadowy wraith, and it’s more difficult to sustain the sense of mystery and thrill of atmosphere when we are forced to adjust to the threat that there may be no hope of solution or resolution. The question arises as to why London has an almost romantic attachment to the legend of ‘Saucy Jack,’ an insular and singular sense of ownership, when it is more likely he was a felonious predator-citizen of the world. If their culprit escaped to spree across continents, it is probable his identity will never be known.

Jack the Ripper in the World

These killings, world wide, were described in the newspapers as being in the style of Jack the Ripper; even if the gruesome details were not explicit, everyone knew what depredations were implied by the use of the moniker. It’s very possible some of these murders were actually the result of ‘Jack’s’ continuing bloodlust. The time frame is the lifespan of a potential killer expected to exhibit his criminal tendencies around age seventeen; he might continue until retirement age, if remaining at large and unchecked, as, for example, a suspect like James Kelly, (1860-1929).

Sometime prior to 1888, Russia, ‘a series of similar crimes’: Ashburton Guardion, 22 February 1889.

1888, ‘Not many months’ before 16 November, Texas, 12 victims (“chiefly Negro women”): Otego Witness.

1888, 31 August to 9 November, London, England, 5 victims, dubbed ‘Jack the Ripper’ murders: Jack the Ripper A to Z, Begg, Fido, Skinner.

1888, December, Jamaica, 4 victims: Ashburton Guardian, 22 February 1889.

1889, 24 January, Managua, Nicaragua, 6 victims: Poverty Bay Herald.

1890, 15 December, Mexico, 27 victims (reported day before trial of accused ‘El Chalequero’): New York Times.

1890, 20 December, Mexico, 8 victims: Fielding Star.

1891, April 25, New York City, New York, 1 victim (Carrie Brown): New York Times.

1892, 6 May, Chicago, Illinois, 2 victims: The Colonist.

1892, 23 May, Australia, multiple victims, (accused Frederick Deeming): New York Times.

1892, September, Vienna, Austria, multiple victims (accused Alois Szemeredy): Evening Post (Wellington).

1893, 22 April, New York, 1 victim (19 March, suspect Frank Castellano, also believed to be ‘Jack’): Poverty Bay Herald.

1893, 13 September, Essex, England, 3 victims: Tampeka Times.

1893, 19 October, Ostburg, Cadizan, 4 victims (in 4 days): Otago Witness.

1894, 27 April, Amsterdam, 2 victims, suspect Hendrick de Jong: New York Times.

1896, 11 June, America*, 9 victims (in two years): Mataura Ensign. (*N.Y., Buffalo, Cincinnati, Denver, ?, Denver, San Francisco (3).)

1897, 24 October, France, ‘nearly a score’ of victims (12) (accused Joseph Vacher): New York Times.

1899, 4 January, Vienna, Austria, ‘another Jack the Ripper murder’ (accused Schgstowitz): Southland Times.

1899, 13 October, Linz, Austria, 2 victims: The Star (Canterbury).

1902, 22 February, San Francisco, California, 8 victims: The Star (Canterbury).

1903, 4 April, Hamilton, Ohio, 5 victims (accused Knapp): Evening Post (Wellington).

1903, 19 May, America, multiple victims, suspect Klosowski (Chapman), from 1888 to 1903, accused of murders in Russia, London and America: West Coast Times.

1907, 29 July, Berlin, Germany, ‘3 little girls’ victims: Bay of Plenty Times.

1911, 3 July, Atlanta, Georgia, 8 victims, (*suspect possibly ‘black man’), New York Times. (*1912, 22 October, “Negro Murderer Confesses” to one murder: Grey River Argus.)

1912, 12 August, Denver, Colorado, 7 victims (in six months): Ashburton Guardian.

1929, 16 December, Dussseldorf, Germany, victim count not specified: John Blunt’s Monthly (U.K.).

Works Cited

Begg, Paul, Martin Fido, Keith Skinner. Jack the Ripper A to Z. London: Headline Book Publishing PLC, 1991.

Casebook Jack the Ripper. Web. 12 May 2011.

Douglas, John and Mark Olshaker. Journey Into Darkness. New York: A Lisa Drew Book/Scribner, 1997.

Evans, Stewart, Paul Gainey. Jack the Ripper First American Serial Killer. New York: Kodansha America, Inc., 1996

Graysmith, Robert. The Bell Tower The case of Jack the Ripper finally solved…in San Francisco. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, Inc., 1999.

Jack the Ripper In America, Discovery Channel television documentary, 2009.

Jakubowski, Maxim and Nathan Braund, Editors. The Mammoth Book of Jack the Ripper. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc.,1999.

Marriott, Trevor. Jack the Ripper: The 21st Century Investigation. London: John Blake Publishing Ltd, 2005.

Rumbelow, Donald. Jack the Ripper The Complete Casebook. Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc., 1988.

Sharkey, Terence. Jack the Ripper 100 Years of Investigation. Dorset Press, 1987.

Sugden, Philip. The Complete History of Jack the Ripper. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994.