by Denise Noe

First published in April/May, 2004, Volume 1, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Most contemporary people who are familiar with Governor George Robinson know him as the attorney who so ably defended Lizzie Borden. Indeed, the most intelligent move Borden family attorney Andrew Jennings made in this case was probably calling on Robinson and asking him to be Miss Lizzie’s primary defender.

Robinson had enjoyed a most distinguished career in both law and politics and, as Frank Spiering points out in Lizzie, “he possessed one invaluable credential: as Governor, in 1886, he had appointed Justin Dewey [the presiding judge in Lizzie’s trial] to the Superior Court system for life.”

At the Borden trial, Robinson proved deft in examining witnesses and eloquent in his arguments. His cross-examination of Adelaide Churchill skillfully punched holes in the state’s case. The prosecutor had just established that Churchill had found Lizzie wearing a pale blue dress soon after her father’s murder. The following comes directly from Spiering’s book:

“Did you see any blood on her dress? [Robinson]

No, sir. [Churchill]

On a dress as light as that, if there had been any blood you would have seen it, wouldn’t you?

I don’t know. I should think if it was in front I might have seen it.

You were right over her fanning her?

Yes, sir, I stood in front of her.

You afterwards saw her with Miss [Alice] Russell [another neighbor and friend of Lizzie’s] and she was lying on the lounge?

Yes, sir.

At that time did you see a particle of blood on her dress?” [Robinson]

No, sir. [Churchill]

On her hands?

No, sir.

On her face?

No, sir.

Or any disarrangement of her hair?

No, sir.”

If the prosecution’s theory of the crime was correct, Lizzie had repeatedly swung a hatchet or some other sharp instrument onto her father just minutes before Adelaide Churchill saw her. Yet she was spotless and without a hair out of place.

Robinson’s summation was a masterpiece of persuasiveness. As quoted in David Kent’s Forty Whacks, Robinson began, “One of the most dastardly and diabolical crimes that was ever committed in Massachusetts was perpetrated in August. 1892, in Fall River. . . . we are challenged . . . to find somebody that is equal to that enormity, whose heart is blackened with depravity, whose whole life is a tissue of crime, whose past is a prophecy of that present.” The obvious implication was that they must look elsewhere than to Lizzie Borden, a gentlewoman of good works with charitable groups like the Fruit and Flower Mission.

He pointed to Lizzie’s cleanliness in the aftermath of two hatchet slayings and the failure of the prosecution to either produce the murder weapon or account in a reasonable manner for its disappearance. When talking about the mysterious weapon, he showed a wry, if unavoidably macabre, sense of humor.

“You have had all the armory of the Borden house brought here,” the attorney told the jurors. “First, these two axes. I put them down because they have the seal of the Commonwealth; they are declared innocent.”

“Then I pick up this one [the plain-head hatchet] and they tell me it is innocent and had nothing to do with it. I put it down in good company. I pick this one up [the claw-hammer hatchet] and they tell me today that this is innocent and I put it down immediately in the same good companionship.”

Finally, the Governor came to “this little innocent-looking fellow called the handleless hatchet.” If the handleless hatchet presented as the possible instrument of death had actually been used in the dirty work, then what had happened to the handle? The prosecution suggested that Lizzie had broken it off, then burned it in the stove in which an officer had found a charred but not destroyed roll of paper. In Spiering, Robinson asked incredulously, “. . . did you ever see such a funny fire in the world? A hard wood stick inside the newspaper and the hard wood stick would go out beyond recall – and the newspaper that lives forever would stay there! What a theory that is! So we rather think that our handle is still flying in the air, a poor orphan handle without a hatchet, flying around somewhere. For heaven’s sake, get the one hundred and twenty-five policemen of Fall River and chase it . . .”

In Kent, we see how frequently Robinson played the “gender card.” At the time, only men could serve on juries and he cleverly manipulated the jurors’ expectations about the proper role and behavior of women, especially upper-class ladies. The defender noted that the prosecution contended she had the opportunity to commit the murders because “she was in the house.” This fact of opportunity should not be held against her, he cautioned, since she was right where they all believed a woman should be. “I don’t know where I would want my daughter to be, than to say that she was at home, attending to the ordinary vocations of life . . .” Robinson said.

As fathers of daughters themselves, the jurors should recognize the mutual affection between Lizzie and her father symbolized by Andrew’s wearing her ring. “He was a man that wore nothing in the way of ornament, of jewelry but one ring—and that ring was Lizzie’s. It had been put on many years ago when Lizzie was a little girl, and the old man wore it and it lies buried with him in the cemetery. . . . that ring was the bond of union between the father and the daughter. No man should be heard to say that she murdered the man that loved her so.”

He reminded the jury that “it is not your business to unravel the mystery” but “to say, Is this woman defendant guilty?”

As he got to the end, the former governor said, “To find her guilty you must believe she is a fiend. Does she look it? As she sat here these long weary days and moved in and out before you, have you seen anything that shows the lack of human feeling and womanly bearing?”

Much in this summation can be criticized, and has been, as illogical, legally beside the point, saccharine, and sexist. But there is no question that it was effective.

Just who was this man who played such a pivotal role in setting Lizzie Borden free?

According to a flattering profile published in The Bay State Monthly of January 1885, “George Dexter Robinson was born in Lexington, [Massachusetts] February 20, 1834.” His childhood and adolescence were spent on his parents’ farm. The physically strenuous chores of a farm boy left him muscular and tanned. However, he did not want a career in agriculture. His superior grades won him entry into Harvard.

After earning his undergraduate degree, he became a high school principal in Chicopee, Massachusetts. He held that position for nine years. “Historical Societies” in Governors of Massachusetts, states that the ambitious Robinson “returned to pursue [his] masters degree studies at Harvard, then studied the law for nine years with his brother before being admitted to the bar in 1866.”

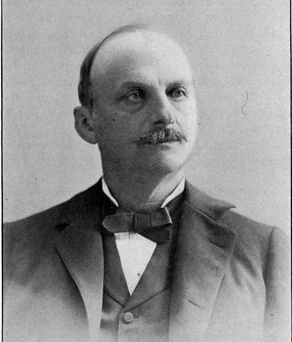

Drawings and paintings of Robinson show a strong-featured man with a prominent, square jaw. His expression radiates an air of confidence but not arrogance. The persona projected would stand him in good stead in his chosen endeavors.

As so many have, Robinson used a successful legal career as a springboard into politics. David Kent wrote in Forty Whacks, “Three had apparently been his lucky number. He had been elected three time to the state legislature, three times to the House of Representatives in Washington, and three times governor of Massachusetts.”

He won his first office in 1874 when he was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives. The Bay State Monthly said, “he was noted for the promptness and fidelity with which he attended to his legislative duties.” That conscientious approach paid off with the state’s constituents, for 1876 saw him in the Massachusetts State Senate. Again quoting from Governors of Massachusetts, “He won a Congressional seat as a Republican in 1877, which he held until he resigned to serve as Massachusetts Governor in 1884.”

When Robinson first went to Congress, he was appointed to a minor committee, that of Expenditures in the Department of Justice. The Bay State Monthly reported that later he was placed “near the foot of the list on the Special Committee on the Mississippi Levees.” Robinson did little to draw attention to himself during the first and second sessions of the Forty-fifth Congress but spent his time studying the ways of his fellow congressmen.

At the third session, he made his first major speech. The subject under discussion was a $4,000,000 bill to improve the Mississippi River. He argued that more the plan needed to be more thoroughly researched before such a great expenditure of the people’s funds was made. He made it clear that he did not see it as an issue, pitting region against region. “Whatever conduces to the prosperity of the West or South will benefit the East and North,” he said. “We are parts of one great whole and, if it is necessary under a proper policy to spend some money from the Treasury of the United States to meet the wants of those States lying along the Mississippi River, I hope it will not be begrudged to them but it should not be done, and the government should not be committed, until the plans have received a careful consideration and the endorsement of the proper officers.”

In the Forty-sixth Congress, Robinson was appointed to the Judiciary Committee. The Bay State Monthly relates that he “took front rank as a debater on points of order.” However, sometimes he was frankly frustrated by the ambiguous nature of Congress’ rules. “If there is a standing and clear rule that guides the Chair,” he once admitted in exasperation, “I have not yet found it.”

In 1883, Robinson entered the Massachusetts Governor’s race. His opponent was the incumbent, Democrat General Benjamin Butler. Robinson waged an energetic campaign, stumping throughout the state and winning votes through his straightforward and eloquent speeches.

During his tenure as Governor, Robinson oversaw some vital developments. The online Energy Time Machine reports that the first government agency regulating energy sales, consumption, prices and consumer advocacy was formed when Robinson approved the Massachusetts Gas Commission on June 11, 1885.

Governor Robinson was instrumental in bringing much-needed improvements to Massachusetts’ prison system. In the words of mass.gov, criticism that the prison at Concord “was not producing adequate revenue through its vocational shops” led Governor Robinson to sign an 1884 bill “that ordered the return of prisoners to Charlestown state Prison and established the Massachusetts Reformatory at Concord. This institution became a place where those under the age of thirty could learn a trade to be used upon their return to the community.”

As Governor, Robinson did much to better the lot of common people. He proposed a law requiring that every school student be provided textbooks free of charge; it passed, making a real education accessible to the economically disadvantaged. According to “Historical Societies” in Governors of Massachusetts, “He also created a requirement that corporations pay workers weekly and established the Commonwealth’s first State Board of Arbitration to resolve disputes between workers and employers.”

After serving as Governor, Robinson returned to the private practice of law where he was much in demand and took the case that would define him as the famous defender of Lizzie Borden for generations of crime buffs. She paid him $25,000 for his services, an extraordinary fee for an attorney in that era. Robinson died on February 22, 1896, and his remains are interred at Fairview Cemetery in Chicopee, Massachusetts.

The powers that George Dexter Robinson wielded in the practice of law were well honed and considerable. They undoubtedly resulted in many clients being both free and grateful though none would ever be so famous as Lizzie Borden, in whose defense he secured a permanent place for himself in America’s most perennial murder mystery.

Works Cited

Energy Time Machine – Events in Energy History. California Energy Commission, 22 April 2002. 26 March 2004 <http://www.energyquest.ca.govtime_machine/>.

Kent, David. Forty Whacks New Evidence in the Life and Legend of Lizzie Borden. Emmaus, PA: Yankee Books, 1992.

Spiering, Frank. Lizzie: The Story of Lizzie Borden. NY Random House, 1984.

Webber, Fred W. “George Dexter Robinson.” The Bay State Monthly, January 1885: 177-185. 26 March 2004 <http://cdl.library.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/moa/sgml/moa-idx?notisid=AFJ3035-0002-25>.

Wieneke, David, Ed. “George Dexter Robinson (1834-1896).” Governors of Massachusetts Interactive State House. 26 March 2004 <http://www.mass.gov/statehouse/massgovs.htm>.

Wieneke, David, Ed. “Local Historical Societies in Massachusettes.” Interactive State House. 26 March 2004 <http://www.mass.gov/statehouse/societies. htm>.