by Denise Noe

First published in Spring, 2012, Volume 7, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

In attorney Andrew Jackson Jennings’ opening statement to the jury that decided the fate of Lizzie Borden, he issued a ringing challenge to the prosecution: “Mr. Foreman and gentlemen, I contend that as to the weapon, they have either got to produce the weapon which did the deed, and, having produced it, connect it in some way directly with the prisoner, or else they have got to account in some reasonable way for its disappearance” (Trial, 1320).

I argued in a previous Whittling entitled “What Happened to the Weapon?” that the government’s failure to adequately meet this challenge was a major reason Lizzie was acquitted.

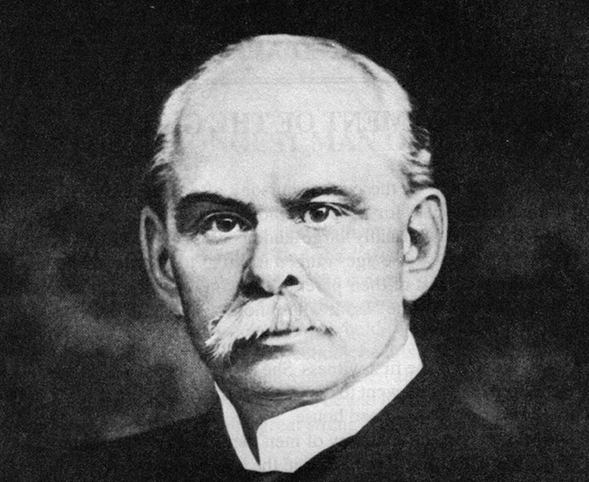

Who was the able lawyer who made this astute point? Andrew Jackson Jennings was born on August 2, 1849 in Fall River, Massachusetts. His parents were Andrew M. Jennings and Olive B. Jennings, previously Olive B. Chace. Although his parents undoubtedly named him after his father, it seems likely they gave him the middle name Jackson in honor of the seventh president of the United States, Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson, whose second term had ended in 1837, 12 years before our subject’s birth.

The “Andrew Jackson Jennings” section of Our Country And Its People: A Descriptive and Biographical Record of Bristol County Massachusetts reports that he was “descended from one of the oldest families of Tiverton, R.I. … and the third son of Andrew M. Jennings, who was born in Fall River, Massachusetts, in January, 1808, and died in 1882, having been for some thirty-five years the foreman of the machine shop of Hawes, Marvel & Davol.” The article continues that there were eight children born in the marriage of Andrew M. and Olive B. Jennings, five of whom died as babies (Country, 739).

According to Len Rebello in Lizzie Borden Past & Present, young Andrew Jackson Jennings attended public schools in Fall River before heading to Mowry and Goff’s Classical School in Providence, Rhode Island. He attended Brown University and graduated in 1872. A Descriptive and Biographical Record of Bristol County Massachusetts notes that he graduated with special honors and was active in college sports.

Apparently impressed with the field of education, Jennings initially made his career in that area as he became the principal of the Warren High School in Warren, Rhode Island, and continued in that capacity for two years.

He sought a change of career in 1874 when he began studying law. In 1876, Jennings graduated from Boston University Law School. Soon afterward, he was admitted to the bar.

Before finishing law school, in 1875, Jennings began serving on the Fall River School Committee. While working as an attorney, he continued that service until 1878.

He went on to a career in politics, serving in the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1878 to 1879 and in the Massachusetts State Senate in 1882. Our Country And Its People states, “During his three years in the House and Senate he was an influential member of the judiciary committee . . . He was active in securing the passage of the civil damage law in the House and the introduction of the school house liquor law in the Senate.” The article lauds him as “a natural orator” who was “eloquent” – qualities that he certainly put to use in his defense of the legendary Miss Lizzie. The piece continues that this excellent speaker made “the memorial oration for the city of Fall River” on the day that “General” Grant’s funeral was held (Country, 740). This writer believes that the “General” was also the President Ulysses S. Grant and does not know why he would be referred to by his military rather than political title in the article.

According to Rebello, Jennings “practiced law in Fall River with James Madison Morton for fourteen years. Morton was appointed to the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts in 1899. From 1890-1892, Mr. Jennings was engaged in a law practice with John S. Brayton, Jr. At the time of the Borden trial, Jennings was practicing law with a young associate, Arthur Sherman Phillips” (Rebello, 196).

Since Jennings had long been Andrew Borden’s friend as well as his attorney, it was natural that reporters from the Fall River Daily Globe sought him out in the aftermath of the murders, slayings that had been committed on August 4, 1894, only two days after Jennings had celebrated his 45th birthday. According to Ann Jones in Women Who Kill, Jennings told the Daily Globe journalist, “A most outrageous, brutal crime . . . and absolutely motiveless – absolutely motiveless” (Jones, 219). The first part of the statement was undoubtedly true. However, the pronouncement of an unsolved crime as “motiveless” seems a bit bizarre as neither Jennings nor anyone else could know with any certainty what the motive might be. Indeed, even if the murderer was a stranger who butchered Abby and Andrew out of sheer cruelty, that cruelty could itself be accounted a motive.

When Andrew Jennings became the attorney for the accused Lizzie Borden, he recognized the truth that a lawyer in a complicated and high-stakes case cannot function as a one-man band so he put together the “dream team” of the late 1890s. The Andrew Jennings Room” segment of the Lizzie Borden Bed & Breakfast website reports, “After Lizzie’s arrest on August 11th, Jennings sought the help of Colonel Melvin O. Adams, former assistant district attorney for Suffolk County of Massachusetts. . . . By the start of the trial . . . Jennings had found help in George D. Robinson, the former Governor of Massachusetts.”

At trial, Jones quotes Jennings as seeming to concede in his opening that his client, Lizzie Borden, might have had a motive to murder one of the victims but demurring strongly on her having any reason to murder the other. He stated, “The Government’s . . . claim . . . is that whoever killed Abby Durfee Borden killed Andrew J. Borden; and even if they furnish you with a motive on her part to kill the stepmother they have shown you absolutely none to kill the father” (Jones, 220).

Jones also quotes journalist Julian Ralph as describing Jennings’ opening as impassioned and moving: “For an hour he championed her cause with an ancient knight’s consideration for her sex and herself. It must have been a strange sensation to that girl to hear, for the first time in ten months of agony, a bold and defiant voice ringing out in her defense. She wiped her eyes furtively a few times, but the tears came so fast that she had to put up her handkerchief” (Jones, 225-226). As Jones correctly notes, the tradition of calling adult women “girls” may have worked to make the defendant seem somehow less responsible and therefore less likely to be guilty than a similarly situated 32-year-old male who would have surely been described as a “man.”

Charles and Louise Samuels in their book The Girl in the House of Hate, a book first published in 1953 when grown women were still commonly called “girls,” note that Andrew Jennings made an opening that was emotionally powerful indeed. He told the jury, “One of the victims of the murder charged in this indictment was for many years my client and my personal friend. I have known him since my boyhood. . . . I want to say right here and now, if I manifest more feeling than perhaps you may think necessary in making an opening for the defense in this case, you will ascribe it to that cause. Facts and fiction have furnished many extraordinary examples of crime that have shocked and staggered men. I think not one of them has ever surpassed in its mystery the case that you are now considering. The brutal character of the wounds as well as the audacity of the time and place chosen, would make this the act of an insane person or a fiend” (Samuels, 110). This last statement was clearly calculated to lead the jury to make a close assessment of his client. Was Lizzie insane? Was she a fiend? Jennings was implying that if the answer to these questions was “no,” she had to be innocent of the offenses.

In his opening, Jennings went on to observe that Lizzie Borden was “up to that time of spotless reputation” (Samuels, 110). The Samuelses continue that during Jennings description of her “splendid church and charitable work,” Lizzie “burst into tears” (Samuels, 111).

However, Jennings in his opening did not appeal purely to emotion. Rather, he promised that the issues in the case would be effectively addressed by the defense. “We shall show you that there were strange people about that house,” he declared. “We shall show you that the government’s statement that this defendant was not in the barn that morning is false. We shall show you that she did go there and was there when the deed was done, so far as Mr. Borden was concerned. We shall show you that the dress which was burned did have paint on it . . . We will introduce evidence to show you that the defendant did not have this dress on on the day of the murders . . .” (Samuels, 112).

The Girl in the House of Hate later reports that Jennings summoned to court a house painter named John W. Grouard. Jennings asked Grouard if Miss Lizzie had been “in the immediate vicinity” of Grouard’s “tubs of paint” and the witness answered, “I think she was.” Then Jennings asked him when he painted the Borden residence and drew forth the reply, “In May, 1892.” The Samuelses then write, “Mr. Jennings smiled, because this was about the time the dress Lizzie destroyed – on which paint had been smeared accidentally, according to the defense – had been made” (Samuels, 114).

The quotes chosen above illustrate why Jennings was such a good attorney: he appealed to both emotion and intellect. He led the jury to feel sympathy both for himself and his client. He also pointed out vital evidentiary failings in the prosecution’s case. The last example is especially on point regarding evidence. Lizzie’s burning of a dress soon after the murders damned her in many people’s minds, but Jennings’s questioning of house painter Grouard made her explanation that she had destroyed a paint-spattered garment plausible.

Andrew Jackson Jennings appears to have been a man of real feeling. Jones describes his reaction to the acquittal as demonstrating a genuine emotional investment in the case – and his client. Jones writes, “Mr. Jennings, almost in tears, shook Mr. Adams’s [Melvin Ohio Adams, one of the Lizzie’s other attorneys] hand, saying in a breaking voice, ‘Thank God’” (Jones, 232).

Jennings’ victory in the Borden case must have made a favorable impression on the public as when a vacancy came up in the position of district attorney for the Southern District in Massachusetts, Jennings was elected to fill that seat in November, 1894. The next year, 1895, he was reelected to serve the usual three-year term.

The busy Mr. Jennings was active in many organizations and often held important offices in them. A Descriptive and Biographical Record of Bristol County Massachusetts reports that he was a director of the Merchant’s Mill, the Globe Yarn Mill, and the Sanford Spinning Company. His directorship of both of the latter two businesses underlines the importance of fabric making in the Fall River economy of the period as well as Jennings’ involvement in it. The same article reports that he was a president of the Young Men’s Christian Association of Fall River and a trustee of the Union Savings Bank. Rebello reports that Jennings also belonged to the University Club of Providence, Rhode Island, as well as the Quequechan and Republican Clubs. Rebello also states that Jennings was a member of the Second Baptist Church, which was sometimes called the Baptist Temple.

Jennings eventually became a member of the Fall River Historical Society. This would seem a very appropriate association since so much of the organization’s work is devoted to the Borden case!

While pursuing a very active public life, Jennings did not neglect the private sphere. He was married to Marion F. Saunders. Two children were born during that marriage, a boy and a girl. The boy was Oliver Saunders Jennings. The girl, named Marion after her mother, would as an adult become Mrs. Dwight Stowe Waring.

Andrew Jackson Jennings died on October 19, 1923. He is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in Fall River, as are two of his most famous clients, Lizzie Borden and Andrew Borden.

He is honored by the Lizzie Borden Bed & Breakfast with an Andrew Jennings Room on the third floor.

Works Cited

“Andrew Jackson Jennings.” Our Country And Its People: A Descriptive and Biographical Record of Bristol County Massachusetts. Boston: Boston History Publishers, 1899. Print.

Jones, Ann. Women Who Kill. Boston: Beacon Press. 1996. Print.

Martins, Michael and Dennis Binette. Parallel Lives: A Social History of Lizzie A. Borden and Her Fall River. Fall River: Fall River Historical Society, 2010. Print.

Rebello, Leonard. Lizzie Borden: Past and Present. Fall River: Al-Zach Press, 1999. Print.

Samuels, Charles and Samuels, Louise. The Girl in the House of Hate. Greenwich, CT: Fawcett Publications, Inc. 1962. Print.

Widdows, Harry, Stefani Koorey and Kat Koorey. The Trial of Lizzie Andrew Borden, Volume 2. Fall River: PearTree Press. 2009. Print.