by Michael Brimbau

First published in Fall, 2009, Volume 6, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

A NEW BEGINNING

The young barmaid brought over a freshly filled kerosene lamp, as Horatio Gunn held up a stubby finger and ordered another ale. Iram Smith adjusted the lantern, and, moving closer to the light, studied an unfolded piece of paper under the dancing flame. Joshua Remington pulled his chair closer, leaned over, and scrutinized the shadowed legal document in the man’s hands.

“So, Horatio, you say there are four of us. I see only the three of us signed here,” said Joshua, somewhat suspiciously.

“Relax, Joshua. I’m sure Charles will be here soon, then we will have four.”

Iram took a series of gulps from his glass and ordered another before the barmaid could walk away. “Have another ale, Joshua,” he suggested.

“No, no, I have had two already,” he insisted, waving the girl away. “I don’t like mixing business matters and drink.”

“Afraid you may be procuring a horse with three legs, are we Joshua?” kidded Horatio, a snide twinkle in his eye. Iram and Horatio broke into hardy laughter. Eying them dubiously, Joshua soon joined in the laughter, even though the joke was at his expense, and shouted to the barmaid to return with another ale.

That moment, the tavern door opened, an icy, stiff wind and a few snowflakes howled in, the lights on the tables flickered, and the fire in the near-by hearth cracked and flared, fed by a fresh, cold, crisp air. All eyes were

on the smartly dressed stranger as he surveyed the room.

“Oh, here he is, gentlemen,” announced Horatio, waving the man over.

“Good morning, gentlemen. I’m sorry I’m late, Horatio,” begged Charles Trafton. He removed his fur-collared coat and neatly draped it over the back of the chair. Charles Trafton was a very tall, handsome man of about thirty, with tight, thick, spirally hair, a firm, long nose, long hanging sideburns, all above a square, but gentle, chin. Almost a foot taller than all his associates, he flung his gangling leg over the back of the chair and fed it beneath himself, plopping himself down. The service at the Wilbur Tavern being excellent, a full glass of ale was soon before him. He delivered a broad smile and winked at the friendly serving girl.

“Well, we are all here,” declared Horatio. “Everyone has been over the particulars . . . a quarter share for each of us?” He scanned the table for everyone’s approval. Trafton was distracted by the eye-catching barmaid as she glided from table to table, delivering drinks. He scrutinized her through the beer suds in his glass, which he held close to his lips, and twisted his head around for a better look, until his chin was almost behind his shoulder. Iram casually leaned over to rib him with some friendly advice.

“Shame, shame, Charles,” he said with a wink and squeeze of the man’s shoulder. “She is old enough to be your daughter.”

“No, I was not . . .” Trafton’s defense was interrupted and a polite request was made for everyone’s undivided attention.

“Charles, are you with us on this?” appealed Horatio. “We have all signed and are waiting for your John Hancock, as it were.” Trafton fed the document up and down through his fingers, while Iram slid the lantern over to give him better light.

“You are sure this is a good investment, Horatio? I am new to the city and just purchased a lot on Second Street to build a home. I am fully extended.”

“Are you backing out, Charles?” inquired Joshua, placing his spectacles on and reclining in his chair to stretch and massage his bulbous waistline.

“No, I have not stated so.”

“That is great news then, Charles,” said Joshua, guzzling his drink. The bitter ale he just ordered no more than five minutes ago was nearly gone. “You could have done much worse moving from Dighton to Fall River. It’s a growing city.” He slurred his words as he spoke. “Who’s building your place?” he asked, leaning over as if to learn a secret.

“Southard Miller.”

“What, the new fire chief?’ shouted Joshua, in disbelief. “Didn’t he let the entire city burn down two years back?”

Everyone at the table boomed with laughter.

“Now that old Southard announced he may run for mayor, perhaps he will rebuild the whole of town from the ashes single-handed . . . starting with Charles’ place?” roared Joshua Remington. He continued his laughter, spilling his beer and wiping the tears from his eyes.

On the other hand, Charles Trafton could see no humor in needling his friend Miller.

Horatio Gunn stood up and stretched out his arms, waving his hands in an effort to control the rowdy group. “Now, now everyone. Let’s keep this civil. Southard Miller is a good man,” said Horatio.

“Aye, but I don’t think he can beat Samuel Brown,” chinned Iram.

“Whether he will make a better mayor than a carpenter,” declared Horatio, “will be a discussion better left for another time gentlemen. The time is late and the wife awaits. Now, Charles, you are acquainted with the parcel we are purchasing? It’s a little over 80 rods and sits on the corner of Bedford and Rock Streets. Prime property, my boy. As you can see for yourself, the city is growing at a breakneck pace; there is construction all around us. The city is quickly rising from the ashes of the great fire of ‘43. Why, right next door, as we speak, they are setting the granite corner stone for a new town hall.”

“So, you think this as a good investment, Horatio?” asked Charles, inspecting the deed in his hand one last time.

“Look,” insisted Iram, leaning over, “by the end of next year, if you are not happy, you are guaranteed to sell and double your share. If not, any one of us will be prepared to buy it back, plus interest. You can’t go wrong.”

“What say you, Charles?” summoned Horatio, tactfully handing him a quill pen.

“Count me in, gentlemen,” proclaimed Trafton, with a proud smile.

“Another round of ale,” yelled Joshua Remington, holding his glass high in the air and spilling the remainder of the ale around him. All the mugs were filled once more, and the four investors raised their glasses and toasted a new beginning and a promising deal.

THE UNKNOWN CHARLES TRAFTON

Of course, the account you have just read may never have happened, and was based wholly in fiction—though much of it has its basis in truth. Very little is known about the particulars behind the real estate transaction that took place between the four men, apart from the fact that it actually occurred in 1835.

Of course, the account you have just read may never have happened, and was based wholly in fiction—though much of it has its basis in truth. Very little is known about the particulars behind the real estate transaction that took place between the four men, apart from the fact that it actually occurred in 1835.

The focus of the yarn was to introduce us to Charles Trafton. His notoriety, if we can consider it as such, was secured on a hot August day in 1892, when Lizzie Andrew Borden became the prime suspect in the murders of her father and stepmother. It was also on that dreadful day that 92 Second Street, one of the most famous and now celebrated residences in America, earned its fabled badge of infamy.

Charles Trafton was the first owner of 66 Second Street in Fall River, Massachusetts, which was later changed to 92 Second Street in 1875. It is believed that the construction was procured by Trafton for his personal use, and built by Southard Miller of Fall River. City directories reveal Miller’s occupation to be that of carpenter, though unlike the fictional narrative above, he served as fire chief for the city between the years 1860 to 1869, and had an unsuccessful bid for Mayor of Fall River in 1868—well after Miller’s commission to build the infamous Second Street building in 1845.

Charles Trafton, unlike Miller, partook of a much more humble and private existence. Instead of mingling in city politics, Trafton worked as an overseer of carding at the Wamsutta Woolen Mill in Fall River. (Carding wool is a method by which raw wool is combed and fibers straightened through a series of rollers, preparing the raw material and making it ready to be spun into thread.) Very little is known about his personal life, separate from what we can discover in old city directories and government birth and death records. Charles Trafton was born in Dighton, Massachusetts, just ten miles north of Fall River in late 1804, to Snow and Priscilla Trafton, and was the youngest of five children.

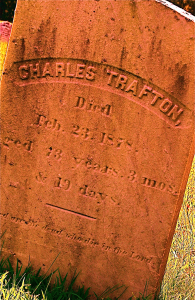

In his seventy-three years of life, Trafton was married twice. His first wife, Hannah, gave life to a male heir, also named Charles. Sadly, baby Charles had life taken away when he was only ten days old. He was Trafton’s only child. This was not the only sorrow Charles Trafton had to endure in life. Eight years after the mournful death of his newborn son, Hannah Trafton succumbed to consumption, and died in the crest of winter at the youthful age of thirty-two. A short two months after Hannah’s untimely departure, life was awarded to Emma Lenora Borden, who was born in March 1851, to Andrew and Sarah Borden.

After enduring fifteen years as a widower, Charles found romance, if not love, once again, and was wed on Christmas Eve, 1866. And what a wife she must have been. The new adoration in his life was one Susan A. Rossiter Little.

Susan A. Rossiter was a local girl, born in the near-by town of Dartmouth, Massachusetts. He was sixty-one and she was thirty-eight—twenty-three years his junior. Charles Trafton was Susan Rossiter’s second husband. Approximately six years after they wed, Trafton sold the house at 66 Second Street to Andrew J. Borden, and moved to South Somerset, across the Taunton River from Fall River.

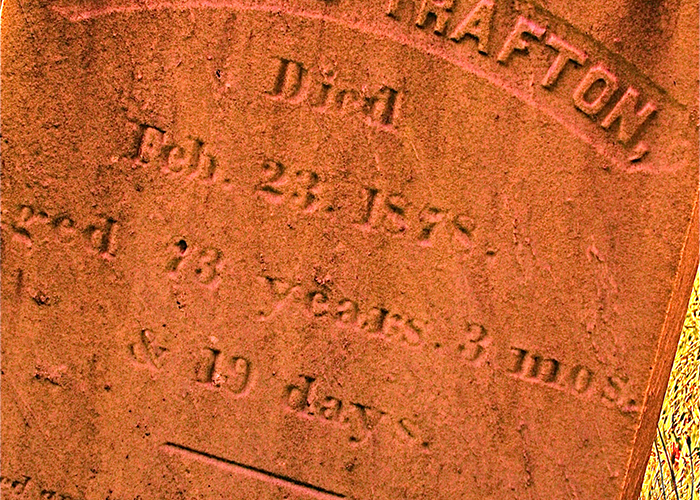

Sadly, a short six years later, in 1878, Charles Trafton was dead—fourteen years before the Borden murders. In his last will and testament, Trafton left all his worldly assets to his surviving wife Susan.

Eighteen months after Charles Trafton’s death, Susan A. Trafton pursued love once again and married for the third time, to an Italian immigrant named Francis De Caro. At some time, Susan A. Trafton De Caro moved out west, where she eventually died in the spring of 1898, twenty years after Charles, in Denver, Colorado, leaving her barber husband a widower.

Charles Trafton was quietly buried in the North Burial Ground on North Main Street in Fall River. This is the oldest city-owned cemetery, having been developed thirty years before the more desirable, if not more fashionable, Oak Grove Cemetery. Oak Grove Cemetery was established as part of the rural garden cemetery movement. Its park-like setting was a pleasant and restful place to visit, with winding roads, fenced-in plots, and meticulous gardens. In comparison, the North Burial Grounds has long, straight lanes, all in rows. It is a more pragmatic layout, with little to no consideration given to ornamental landscaping or decorative terrain.

When Oak Grove Cemetery was established, many of the affluent Victorian elite willfully abandoned the old burial ground in the north end of the city, for the more central and opulent location, going as far as to disinter their loved ones and rebury them at Oak Grove. With the exception of a few Revolutionary War heroes, Charles Trafton has very little in the way of notable company.

The first grave in the Trafton plot is unmarked, and occupied by his infant son, Charles Trafton (Jr). The first gravestone in the plot is of his wife Hannah. The next stone is for Charles Trafton himself, closely followed by a twin headstone of Susan A. De Caro, Trafton’s second wife. In the same plot, and in an unmarked grave, is buried one Rhoda White. Rhoda was Trafton’s housekeeper, and occupies a grave just behind and to the right of Susan.

We can only speculate that Charles Trafton must have been a kind and decent man. Proof of this is the love he extended to his housekeeper, allowing her to be buried in the family plot. And, we can easily assume, that the ultimate proof may be the fact that Susan A. De Caro, who had wed three husbands, chose to be buried beside her beloved Charles when she died.

In my limited exploration into Trafton’s background, I was unable to uncover the date he made his move to Fall River from Dighton. The earliest I can discern is 1835, the date of the real estate transaction mentioned earlier. On this parcel was the estate home of the former John C. Borden, who had died in 1833. Borden had built what can only be described as the most colossal mansion ever erected in Fall River. Arthur Phillips, author of The Phillips History of Fall River, describes the edifice as “built in 1827, contained fifty-five rooms with floors, ceilings and doors of hard pine and with wainscoted walls and hand carved interior finish.” Later, this building would be known as the Exchange Hotel, and in the building’s last days, it would be known as the Gunn Mansion.

Whether Charles Trafton’s real estate interest included shares in the buildings on the property, or a separate parcel of land, would need further study to uncover. Horatio Gunn had purchased the entire property by 1844, and continued to employ it as a hotel. Eventually, Gunn used the building as a private residence. The Gunn Estate was torn down in 1910, and the Second District Court house constructed in its place. The courthouse still stands today, on the corner of Rock and Bedford Street. Ten years after the real estate transaction between Charles Trafton and his three colleagues, Trafton had his dwelling built on Second Street.

If not for the legendary murders, the story of Trafton’s existence would have little reason to see daylight. In many respects, the same could be said about Lizzie Borden. If 92 Second Street was never built, Lizzie may have never been indicted for the murders of Andrew and Abby, and the history of Andrew Borden and his daughters would play a miniscule and insignificant roll in Fall River’s rich history.

GREEK REVIVAL ERA AND THE BORDEN HOUSE

230 Second Street, commonly known as 92, was built in the Greek Revival style. The Greek scheme was popular sometime after 1820, and remained the fashionable motif into the 1850s. The design became so popular that it was used on the common cape cod, cottage, and multi-family homes. A casual inspection through A Guide Book to Fall River’s National Register Properties lists twenty-five homes that were built in Fall River in the year 1845, twenty of which were in the Greek Revival style. This was the same year the Charles Trafton/Andrew Borden house was constructed.

Earlier Greek Revival homes were pure in their design. The attempt to reproduce the classic angular outlines of a Greek Temple were more strictly adhered to. Many of these homes were grandiose and palatial in appearance. A perfect example is the William Lindsey House/1844 on North Main Street in Fall River, between Locust and Walnut Streets, and the John Mace Smith House/1844, which is next door. Regal examples were usually adorned with massive, tall, ostentatious, fluted ionic columns. These held up overhanging pediment end gables, which always faced the main entrance or the front of the property. Corner pilasters were usually ornate and capped with flowered carvings and leafy embellishments. Classic examples were always painted white and utilized flat siding boards on their facades, to imitate stone or marble, and finished off in clapboard on the remaining three sides. The Jefferson Borden House/1840, at 386 High Street, in Fall River, and the Carr-Osborn House/1842, on Rock Street a block away, are typical of this design.

Simple and more modest specimens incorporated plain paneled pilasters or wide decorative corner boards flush to the building, and minus the columns or prominently extended pediments. Some more modest designs limited the columns to small porticos or stoops. Windows were usually six over six, divided lights, draped in shutters, with decorative eyebrow lintels. The front door, in many cases, was off-center, as in the Andrew Borden house, and decorated with sidelights, and flush, framed pilasters. Commonly, entrances were capped with a tall, simple or impressive, multi-tier lintel.

The Borden house on Second Street is a perfect example of a modest multi-family Greek Revival residence. Another, this one also with connections to the Borden story, is the small cottage in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, where Emma Borden was staying the day of the murders. Historically known as the Brownell House, it sits on Green Street and was an excellent example of a small, unpretentious Greek Revival home. If you compare old photos of the Second Street home and the Brownell home, you will discover that they were nearly twins. Recently, new owners skinned all of the original trim and clapboard off the Brownell House, completely changing it from its Greek Neoclassical design to a plain modern Jane.

THE BORDEN HOUSE AND RAILROAD FLATS

When Andrew Borden purchased the Second Street property in the spring of 1872, it had been standing for twenty-seven years. With all the changes and urban development that has occurred in Fall River’s lower Corky Row neighborhood in the past fifty years, it is a fortunate stroke of luck that the structure has survived. Much of its endurance could have been the direct result of having a business attached to it, making the property more valuable.

Countless narratives and descriptions of the Borden house have appeared in books, magazines, and newspapers over its 164-year existence. Most of these are just a regurgitated account, as one writer sponges off another. Very few authors today take the time or expense to travel and visit the Borden property, or do the weary footwork needed to search out absolute embryonic sources, before composing their versions of the story. Thus, numerous misconceptions, false impressions, and outright inaccuracies have been reiterated and echoed in published transcripts.

When the house on Second Street changed hands from Charles Trafton to Andrew Borden, it contained two separate nearly identical apartments, one on each floor—just the way Miller had built it in 1845. Many writers have chronicled the Borden house by calling these “railroad flats.” This was not true. The interior of 92 Second Street had what could be considered a very typical floor plan for a New England flat—outdated by any modern standard. Approximately 80% of the three- and two-family homes in Fall River have similar floor plans.

A railroad flat, or railroad apartment, can be described as having the rooms in line with a common hallway down the center or along one side. The term is taken from railway sleeping cars or Pullman cars. The term railroad flat is one that is little understood. One of the most common errors is the confusion between a railroad flat and a shotgun house. Even early copies of The American Heritage Dictionary are in error, describing a shotgun house and calling it a railroad flat, both being two distinct designs. Shotgun houses, commonly known as shotgun shacks, are often very tiny and are made up of a series of two or three rooms, one after another, with a back door in line with a front door, thus firing a shotgun in one door would take the shot out the other. First designed in New Orleans, and common in the southern part of the United States, these tiny homes are almost nonexistent in the Northeast. There are none in Fall River to my knowledge.

Many two- and three-family homes, and some large single-family dwellings, in New England had a railroad design floor plan in their attics or upper-most level, containing a long hallway down its center, and rooms to the left and right of it.

92 Second Street never contained a railroad flat. This erroneous rendition was first made popular by Edward Radin. Later, it was repeated by Victoria Lincoln, Frank Spiering, and David Kent in their accounts. I have yet to research where Radin secured the label, “railroad flat,” but my guess would be from newspaper accounts. Early narratives by Edwin Porter and Edmund Pearson fail to use this designation.

FALSEHOODS, MYTHS, AND EXAGGERATIONS

To understand why we believe what we do about the Borden incident, we must carefully investigate the gang of five, Edward Radin, Victoria Lincoln, Anges de Mille, Robert Sullivan, and Frank Spiering. Their books are detached cornerstones for the canards, the twisted truths, the fabricated plots, and inventive scenarios. All best sellers, most portray and present a slightly skewed interpretation of how the author wishes us to see the Bordens, their everyday events, and the house they lived in. Much of their resources and material were enhanced and taken at face value from magnified or inflated 19th century newspaper accounts. In accounts by these five, actual visits were made to Fall River and interviews were conducted; how reliable, can only be guessed at.

In his account, Lizzie Borden: The Untold Story, Radin states that, “The structure had been built as a two-family house with a separate railroad flat on each floor.”

Another popular misconception was that the house was cramped and its occupants enjoyed little or no privacy. Not completely true. Again, Radin declares: “The narrow cramped house, with its peculiar first-floor layout of rooms, was another hurdle. Romance does require a modicum of privacy in order to develop and flourish. But with doors opening into the rooms from all sides, the probability that household traffic might have to pass through at any moment must have been a restraining factor, if not an outright deterrent, to anything beyond formal conversation. More privacy and spontaneity could have been achieved in a crowded railroad station.”

Radin’s portrayal is misleading, over the top, and forsakes us to conclude, speciously, that poor Lizzie and Emma were left barren spinsters because the house had a flawed design. One must admit, a little garnished phrase here, and a sarcastic, if not twisted, perspective there, makes for a good yarn.

Now, the sensational Mr. Frank Spiering is more concise, calling it a “railroad-flat” and “cramped” all in one sentence. In his book, Lizzie, he writes: “In the cramped railroad-flat structure of the downstairs Andrew had…”

Let us take a look at another expose, this one by fiction writer Victoria Lincoln, who published A Private Disgrace: Lizzie Borden By Daylight. Lincoln was in the dark when she wrote that “the little, cramped house was anything but soundproof, and old Yankee voices carry. Lizzie said later that their voices ‘annoyed her.’” My emphasis here is on the words, “cramped house.” In this passage, Lincoln is talking about Andrew, Morse, and Abby having a conversation in the sitting room, and Lizzie overhearing them from her bedroom above. This being August, many of the windows in the house were wide open. Voices from the first level would easily travel out a window and naturally reflect off the Kelly house next door, and back up to Lizzie’s room. Lizzie was not annoyed because of a lack of privacy, or because the place was too tiny, or because they spoke loudly—if Lincoln’s premise is to be believed, she was most annoyed by what was being said.

In another selection from Lincoln’s book, Victoria describes Borden and the infamous horsehair sofa, and further declares: “ . . . when he rests on it his long legs sprawl onto the floor—is still so large for its cramped setting that it must stand with one arm set flush with the door into the dining room.” The truth is that this had more to do with the way the room was laid out than with its size. Though not a large space, it is by no means confining. The sitting room had six doors, a fireplace, and two windows. The ill-fitting sofa had all to do with a bad layout, along with the choice Borden made to place it there. The best location for the sofa would have been by the windows, though it would be the last place a Victorian would place a sofa, due to drafts from the windows. When the house was first built, the sitting room was probably not made for the placing of a sofa. Borden chose to place the sofa in the worst area of the sitting room—not that he had much of a choice.

Emma’s bedroom is a different matter. There, it is more than cramped and borders on claustrophobic. Having lived in Fall River, Victoria Lincoln should have known better. And perhaps she did. Of course, this made for a good tale and a best seller—giving the public what they wanted to hear. Once you visit the Borden house, you will discover that Victoria Lincoln’s telling is nothing but a good fish story.

Lincoln is but one in a long line of popular and successful writers on the Borden case, whose mass publications have reached millions, and adversely influenced the way we view the climacteric events leading up to, and the crucial reasons for, the murders. These authors and their best sellers have become the headspring for skilled researchers and ardent students alike. Much of this material has been imprudently and naively reproduced by writers who transcribe inaccuracies, myths, and legends, replicating unsound or flawed perspectives.

This includes the mean-spirited and callous way the Bordens are characterized. An example of this is Victoria Lincoln’s vile description of Abby, calling her “dismally uninteresting,” “a lonely, self-pitying glutton,” and “an underdone suet pudding,” who “waddles” when she walks. In one vague and confusing sentence Victoria states, “The problem was, in essence, Abby’s fat; if she had weighed thirty or forty pounds less, Andrew Borden might well have died in his bed.” Is she implying that Abby’s weight problem was the cause for the Borden deaths? Lincoln’s descriptions are an over-embellishment, and her gilding of words best left for fiction. Not only is she greatly accessorizing her outline, but there is no need to be so unkind.

Let us take a look at this so-called “cramped” home. 92 Second Street, at the time of the murders, had 2288 square feet of living space on the first and second level. On the other hand, Maplecroft contained 2802 square feet of living space when first purchased by Lizzie and Emma. Both buildings were close in size, Maplecroft containing a little less than 20% more floor space. Maplecroft is a little over 500 square feet larger than 92 Second, yet authors such as David Kent and Frank Spiering mention that Maplecroft was a “mansion”—another misleading appraisal. The Second Street house was by any standards, today or then, ample, if not spacious. Later, Lizzie added 325 square feet more to Maplecroft, building another bedroom towards the rear of the house.

This is not to say that the house on Second Street was without problems, some which bordered on the issue of privacy—most homes do. One specific case was on the second level, and the worst example existed between Lizzie’s and Emma’s rooms. Yet, there is nothing written in the way of complaints from either sister. The difficulties with privacy and lack of living space should not have been any more of an issue than any other home. Certainly not as great or as dire as some authors have reported it. Even if it was, it is no defense, justification, or reason for a scenario leading up to murder.

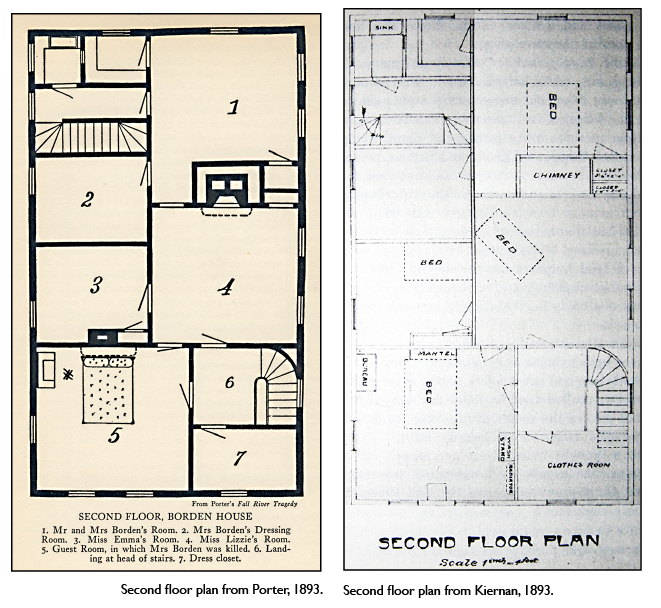

When Borden first purchased the building he had many changes made, converting it from a two-family to a single-family home. On the first floor, Andrew removed the wall separating two bedrooms on the north side of the house, thereby creating one large formal dining room. Other than removing the kitchen to make a bedroom for himself and his wife, the changes on the second floor were minimal. The sleeping quarters desired were gained by simply locking off doors. Where the dining room is currently situated on the first floor, on the second, the space was left unchanged and contained two bedchambers. One portion became Lizzie’s bedroom, and the other a dressing or changing room off Andrew and Abby’s bedroom. The senior Borden’s bedroom was once the kitchen for the apartment on the second level. The parlor on the left at the top of the front stairway became the infamous guest bedroom. The door between the second floor parlor and the sitting room, and the door between the old kitchen and sitting room, were sealed. The favorable outcome was a bedroom for Emma in what was the second floor sitting room—the unfavorable effect was that Lizzie now had to first walk into Emma’s room to get to hers. In conclusion, what they ended up with were two mature, unhappy spinsters, in essence sharing a bedroom.

Another change Borden made was to install central heating. Proof of this is revealed by studying the official floor plans put forth to the court by Thomas Kieran, the engineer for the State’s case. (Kieran has excluded all the radiators on his plans, except for the one he displays in the guest bedroom.) Borden had eliminated the fireplace in the second floor parlor, Emma’s bedroom, and the first floor parlor. The original fireplace mantle in the second floor parlor still exists behind the bed in the guest bedroom today.

On the first floor, it is highly likely that Borden had the fireplace mantle removed from the parlor and relocated to the sitting room. Whether intentional or not, this was an unwise and careless decision on Borden’s part, since the mantle did not fit correctly and the door frame leading into the kitchen from the sitting room needed to be cut and hewed to make the large mantle’s sill fit. Modern rumor has it that the original, smaller sitting room mantle was then stored in the barn. The existing mantle in the sitting room is a perfect match to the one in the guest bedroom on the second floor, which was barricaded but never removed. Further inspection shows us that the bookcase situated in the southeast corner of the sitting room today, was, in all probability, constructed using the original mantle that was reported to be stored in the barn.

Now, let us look at one of our favorite authors—the conservative David Kent. Mr. Kent has earned a reputation for being very careful with the facts and writing an excellent account. In this next extract, Mr. Kent writes in Forty Whacks: “As the reporter noted, Andrew had yet to spend a foolish dollar, and foolishness apparently included such things as electricity, bathrooms, or that newfangled invention, the telephone. His only concession to creature comforts for himself and his family was a furnace in the basement.”

He also states: “Except perhaps by the standards of a miser, 92 Second Street was not befitting the Borden and Durfee names. . . . The Borden house still stands, now number 240, appearing, with the exception of a window air conditioner, much as it did that day in 1892.” (Kent’s address for 230 Second Street is incorrect here. Number 240 is the address for the old Dr. Michael Kelly house next door.)

My exception here has to do with the label given Andrew Borden—of being a miser, not wanting to spend a “foolish dollar.” It is true that Borden lived far below his means, but did it make him a miser? Perhaps it did. But what Mr. Kent and others surreptitiously imply was that this was deviant, evil behavior, deserving of condemnation, or dare I say, part of the reason for the Borden deaths. At the very least, David Kent is culpable of repeating this inference and not coming to Borden’s defense, proliferating and snowballing the belief that Andrew Borden must assume some blame. Again, this is overplayed and in all likelihood made popular by contemporary news reports, and over the years it was successively repeated by author upon author, until it became accepted, conventional lore.

The installation of central heating was not cheap and the technology still rather new in the late 19th century. There were very few systems installed at the time, with most systems going to wealthy patrons or into public buildings. William Baldwin, known as the father of central heating in America, had just acquired a patent in 1874 for the serviceable radiator system, perfecting his innovation in the 1880s and making it a commercialized system. It was not until the early 1890s that residential radiator heating systems came into their own, becoming more affordable and marketable to the mercantile classes. Yet, Borden laid down a serious amount of money early on for this recent invention. This entitled skinflint got in on the ground floor when he made this substantial New Age purchase.

Now, we can go on, author after author making our point in defense of Andrew Borden, but I’m afraid that it would take up the greater part of this essay.

THE BORDEN HOUSE FLOOR PLANS

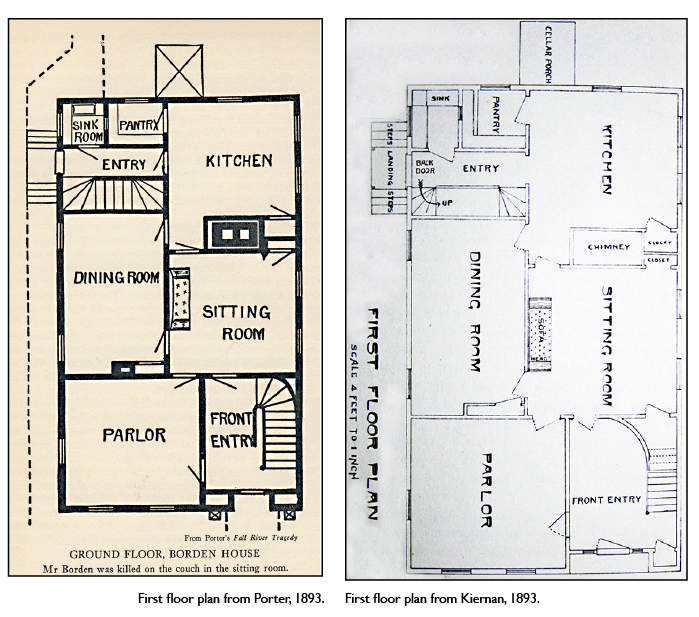

Floor plans of the Borden house were first made public in Edwin Porter’s book, The Fall River Tragedy, back in 1893. Porter’s facsimile of the floor scheme of the Borden house contains some inaccuracies, yet they were accepted and copied countless times by authors such as Pearson, Radin, Lincoln, and many more. The source of these makeshift blueprints are unknown, but the errors within them are plain and obvious to the prudent observer.

The first of these has to do with the main entrance. Porter displays two closets, one on each side of the front door. There should be only one in the southwest corner, and the front door should be off center to the room, favoring the north side. The second error reveals that a fireplace is not shown in the sitting room, but is present in Lizzie’s bedroom, where there should not be one. The third error has to do with the dining room

closet—it reveals that this door is missing or barricaded. The symbol for “swinging door” is omitted.

As I have mentioned, it is unknown where Porter obtained his floor plans. Thomas Kieran, an engineer and witness for the state, drew up the officially sanctioned floor plans used in court testimony. But, these fall short also, and contain errors of their own—this from an engineer who measured the house and actually performed a penetrating and professional study of the house. Thomas Kieran’s floor plans were used by Agnes de Mille and Frank Spiering in their books.

The first error in Kieran’s blueprints is the omission of the rear entry door on the first floor between the kitchen and hallway. It could be possible that this door was removed and stored away, but I find that unlikely, for it would be of value in winter months. In my brief search, I could not discover any proof that the door was, or was not, on its hinges. Porter’s floor plans of the first floor display a working door. He may indeed be correct. In any event, it is likely an engineer or architect would display a door, whether it was on its hinges or not, since it was typical or common to the construction of the building.

The second fault, which may be one of contention, is that there is no door on the closet by the fireplace in the sitting room. Porter reveals a door. On this account, he is right.

The third error takes us to the front of the house to the door leading into the parlor from the front entry. Kieran has it opening the wrong way, with the hinges on the right when entering the room. This meant that when entering, the door would swing into the center of the room instead of towards the southwest corner. Some may think this of minor consequence, but if testimony came up, or proof was needed, that someone was hiding in the parlor, perhaps behind this open door, which way it swung open would make all the difference.

The fourth blunder is probably the most puzzling. Here, Thomas Kieran omits the bedroom door between Andrew and Abby Borden’s bedchamber and the hallway. The symbol he uses is repeated for the door on Lizzie’s bedroom closet, and the door leading between Lizzie’s room and the senior bedroom. In Edmund Pearson’s book, The Trial of Lizzie Borden, we find William H. Moody, junior prosecutor for the state, describing the interior of the house in his opening statement. Here he notes that the doors between Lizzie’s bedchamber and the guest bedroom, and between hers and Andrew and Abby’s bedchamber, were kept locked from both sides at all times. He also pointed out that there was indeed a door between Mr. Borden’s bedchamber and the back hallway, which was locked “always and upon the day” of the crime. The symbol used by Thomas Kieran designating the passageway is ambiguous and confusing at best.

Though it is well known that the house plans used in the trial were drawn up by Thomas Kieran, one is left to wonder if Edwin Porter’s copy was not in the hands of the prosecution before being passed on and used in Porter’s book The Fall River Tragedy. Not only were there errors found on the actual documented plans by Kieran and Porter, it is important to note that

in William Moody’s opening statement, he falsely states that the front hallway had “two small closets.” When he made his declaration at the trial, was he referring to the floor plans that were later used in Edwin Porter’s book? Or, were the plans in Porter’s book drawn up using Moody’s legal assertion? Moody’s description on the second day of the trial only confuses matters more for scholars of the case.

There are several variants of the Borden house floor plans in existence. Muriel Arnold used one of her own, while Arnold Brown displays one drawn by Anna Brown. One of the most accurate diagrams is the one used in David Kent’s book Forty Whacks. Though he corrects the swing of the door leading to the parlor and other problems, he omits the doors on the dining room closet and Emma’s bedroom closet, and omits the closet that is underneath the stairs in the sitting room.

What can we conclude from all this information? I am not the first to do such a study. The interior of the Borden house has been finely combed over by police, attorneys, engineers, sleuths, authors, and countless others in their search to discover a cause, or make sense of, the ruthless murders that occurred on August 4, 1892.

Taking into account the scores of books that attempt to describe the interior layout of the Borden house, we find that many appear to imply that it was the building that drove its occupants to madness—if only it was not so cramped, and the rooms so badly designed, the walls so paper thin, its style so ancient, and its owner so tightfisted, then perhaps this hideous crime would have never occurred.

ANDREW BORDEN, VICTIM AND VILLAIN

Over the years, excessive significance has been given to the size of the house, its peculiar layout, or the fact that old man Borden was nothing but a surly and presumptuous miser. This was a man who sent one daughter to college, another daughter on an exorbitant trip to Europe, and awarded them both a house as an investment, which he later purchased back from them with cold hard cash. Or, the time he purchased half interest in a property, giving it to his wife for her sister. These are but a few of the kindnesses we are aware of—evil miser or frugal patriarch?

Since it was assumed at the time that the killer had not been discovered, and that Lizzie, a woman, could never have committed such a crime, there was no guilty party or fiend to absorb the blame and souse the public’s thirst for justice. Early on, the press began its search for a villain. Possessing a citywide reputation as a prudent and hard-nosed businessman, Borden fit the mold perfectly—thus, the victim became the malefactor, the mob was satisfied, and the sale of newspapers, brisk. The press contrived its scapegoat, its whipping boy, for a nightmarish homicide that lacked a scoundrel, and Andrew Borden became the stand-in and earned the regretful reputation of rogue early on. How dare he have all that money and not acquire the luxuries it could buy. No wonder he was killed.

For reasons of its own, the press sunk its teeth into the victim, the house he lived in, and the sort of life he led. It chose to exaggerate, overstate, and aggrandize it all, making Andrew Borden the bad guy, the miser, cheapskate, a Scrooge—and they never let go. Over time, one author after another celebrated the labels bestowed on Andrew Borden by the press, measuring the old banker’s character by his billfold. A prolific author, like a prudent journalist, knows what it takes to sell books. Even today, most writers shake Borden’s ethics, condemn his frugality and denounce the choices he made in furnishing his home, almost insinuating culpability in his own death.

One pivotal point we must keep in mind is that the Borden murders occurred towards the end of the 19th century, at the inception of yellow journalism. Fall River, with a population of around 83,000 in 1892, had four major newspapers. Competition in the newspaper industry in America was fierce, and the reporting of news was becoming the making of news—journalists were changing from being considered stenographers to agitators and instigators of information. The reporting of news became the channeling of it. If a story was not interesting enough, one was woven, and if not exciting, broadened, improved and proudly sold without shame.

Idle rumors, along with those not on good terms with Andrew Borden, found journalists climbing over each other to hear their cynical tales and to report back with one better. Andrew Borden was made to shoulder part of the blame for his own brutal death, and that of his elderly wife, due to his simple parsimonious and sagacious nature.

Over the years, few authors have come to the defense of Andrew Borden. Criticizing him and the choices he made fabricates a better story. Few trouble to sieve through the multitude of news reports of the day, and read between the lines, or arrive at their own conclusion, and not just parrot what has been written.

Andrew Borden worshiped money, was a bad father, a scrimpy miser and was killed on a hot August day, and it was all good—good for business.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

How shocked and astonished Charles Trafton would be if he knew the events that occurred in his modest two-family dwelling, and how it became one of the most well known residences in America. What would he have to say if he could witness the hundreds of souls who have slept and been entertained there, and how business endeavors have converted his unlikely abode into an amusement-themed house.

Unfortunately, the historical plaque, which hung by the front door, and naming the house for Charles Trafton, has been removed and replaced with one for Andrew Borden. It is common for a house to take on the name of the person who has made it noteworthy, through fame or infamy, or the name of a famous person who slept or died there. In many instances, the person who built the house is unknown, such as Charles M. Allen—first owner of Maplecroft. Even though Maplecroft was named by its fabled owner, very few know it as the Lizzie Borden House. Instead, it is commonly referred to as simply Maplecroft. Historical guidebooks credit it as Maplecroft/Allen-Borden House. But, even though we name our children, very few of us name our homes.

Another example of a house with tandem names is the Carr-Osborn House on Rock Street in Fall River. This home was built by Holder Borden, truly one of the richest men to ever live in Fall River. Holder Borden had three houses built, one for each of his three sisters. One of these was constructed for his sister Sylvia, who married Joseph Durfee. They, in turn, had a daughter, Elizabeth, who married William Carr. In time, the majestic Greek Revival became known as the Carr House. Later, it was occupied by James E. Osborn, and became his residence for many years. All these men were very successful and wealthy textile magnets and industrialists, known more for amassing wealth than for any monumental achievement.

Today, this elegant Olympian structure, which could have been named for any of these men or women above, is known as the Carr-Osborn house. In the spirit of architectural greatness, this vital, historical home holds its own as a precious antiquity that cries for preservation simply due to its significant architectural design. For this reason alone, this structure should be known by its builder, Holder Borden, or its first occupant Joseph Durfee. Thus, it would be more accurate as the Holder Borden House or the Joseph Durfee House /1842, or possibly a combination of both men. (This is not to be confused with the Borden-Durfee house at 225 Prospect Street. With so many Durfees and Bordens in Fall River, and the multitude of 19th century homes that have survived, this could become confusing.)

Andrew Borden is, by far, the person of interest when we talk about the Second Street house. It is important to keep in mind that even without the nefarious history that has brought considerable regard to the building, the house at 230 Second Street (#92) stands on its own merits as a structure of architectural importance. And just as Joseph Durfee should have his name grace the Carr-Osborn house, some acclaim should be imparted to Charles Trafton. Thus, the proper plaque should be one that reads “TRAFTON/BORDEN HOUSE /1845.”

If it was not for Charles Trafton building his humble home, the Borden murders may have never occurred. With all the controversy behind what has been written over these many years, it amazes me that some savvy writer or author has not bestowed some guilt, or vested some allusive blame on Charles Trafton for the slaughter of Andrew and Abby Borden. Perhaps someone should. There’s a good chance it would make for a best seller.