by Mary Elizabeth Naugle

First published in May/June, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Part of the Lizzie folklore is that she was a thief, possibly a kleptomaniac. This angle on her character has even been worked into solutions of the crime—for instance, in the made-for-television movie, Elizabeth Montgomery’s Lizzie Borden takes an ax, quite literally, from a local dry goods store. But one reason for the original significance of Lizzie’s supposed kleptomaniac tendencies may elude modern students of the crime. Kleptomania was a craze afflicting Victorian women of the middle and upper classes, in America and on the Continent, and by Lizzie’s time had become so well known that it was a favorite target of fun in music halls and vaudeville. Elaine Abelson provides us with two examples. The first, an English ballad from 1867, provides both title and epigraph to her book When Ladies Go A-Thieving:

Ladies, Don’t Go Thieving

Oh, don’t we live in curious times,

You scarce could be believing,

When Frenchmen fight and Emperors die

And ladies go a-thieving.

A beauty of the West End went,

Around a shop she lingers,

And there upon some handkerchiefs

She clapped her pretty fingers.

Into the shop gently popped;

The world is quite deceiving

When ladies have a notion got

To ramble out a-thieving.

The second example she cites comes from a Weber and Fields routine in 1901: “Mrs. Tankton, a wealthy, presumably respectable woman, ‘has been told by her doctor that she has kleptomania and was taking things for it.’”1 Issues as to whether the kleptomania of the nineteenth century was genuine or magnified by a scandal hungry press and public, or whether it was an affliction or a vice, have been debated by doctors, criminologists, and sociologists ever since. Indisputably, though, the phenomenon was part and stolen parcel of its day and is well worth investigating.

Theft in fact and fiction was nothing new. Pirates, highwaymen, pickpockets, and burglars had been plying their trade for centuries. Thieving women were not an innovation either: we had the real life Anne Bonny and Mary Reade among pirates, and female pickpocket rings led by the likes of Jenny Diver. What was new was the emphasis on who they were and where they were. These criminal debutantes were sometimes just that, debutantes. They came from respectable families of comfortable circumstances. They took items of indifferent value, and above all, they gained nothing financially from their exploits.

The where of the new crime was the department store. The upper classes had very little to do with shopping for the daily fare in earlier centuries. The marketplace was not the place for ladies. However, the new department stores were different: they were luxurious in design and wares; above all, they were respectable—all the best people were to be found there. In 1883s Au Bonheur des Dames (Ladies Delight, based on a famous Paris department store), Emile Zola refers to a lace display so enticing that “the temptation was acute, it gave rise to an insane wave of desire which unhinged every woman.”2 Suddenly women of all classes would fall prey to these temptations. According to Abelson:

Aggressive merchandising, which intentionally made it difficult to leave a store empty-handed, combined with new middle class notions of need to submerge traditional moral considerations. . . . “It is not that we need so much more, or that our requirements are so increased,” one woman explained, “but we are not able to stand against the overwhelming temptations to buy which besiege us at every turn.”3

Moreover, this temptation could strike even those presumed to be of the highest moral fiber and topple even the least likely to fall. For example, the French physician Marc (who introduced the term kleptomania) and the famous psychiatrist Esquirol recorded the following case in 1838:

A woman of fifty years, happily married, mother of two young ladies and a son of eighteen, belonging to an honorable family and previously of irreproachable conduct, known for her generosity and beneficence, . . . arrived in Paris and committed larcenies in several retail shops. . . . [She confided that] “I have a crazed envy that drives me to take possession of all that I see, such that if I had been in a church I would not have been able to resist stealing from the altar.”4

An interesting example is given by I. P. James, who found record of a middle aged relative of Jane Austen’s having been caught stealing from a department store. Although she was arrested forthwith, she was kept in comfortable seclusion at the jailer’s home rather than in a cell with common criminals. When she was brought to trial, the jury deliberated only seven minutes before acquitting her.5 This case introduces an additional wrinkle: the double standard in treating thieves and kleptomaniacs. The first were shown in to a jail cell; the second were discreetly shown the door.

Here follows a full transcription of an article first run by the Washington Star, then reprinted by the New Hampshire Daily Telegraph on June 24, 1884. The headline reads “Kleptomania: Among Women of Social Standing in Washington”:

“Lifters? Yes, there are lots of them. We can’t tell how much we lose in a year from shop-lifting,” said an avenue merchant the other day, as he leaned carelessly against the counter, his restless black eyes watching every one and everything in the store with a keenness of a detective. “Kleptomania they call it, where fashionable women are caught with bolts of lace, handkerchiefs, collars and the like smuggled under their wraps.”

“Do you meet with cases of that kind?” asked the Star, with astonishment.

“Many,” was the reply. “There are women of the highest walks of life in this city who are practical shop-lifters. They say it is a disease when they are caught, but I don’t believe that. One woman I caught stealing some lace, however, swore that it was an affliction that she could not control, and offered to bring her family physician to prove it. But I don’t put any faith in it. They have a propensity to steal, and do it rather than buy. Some of these women are of the first families in the city, have wealth, and would pay out almost any amount of money to avoid exposure, yet they will steal, and we have to forbid them the store. Some of them are very clever thieves.”

“How do you catch them?” asked the Star.

“We are always on the lookout, and most of the salesgirls are very sharp. Then, too, we get to know their ways so well that we recognize them very readily. When a woman is very loquacious and affable, and keeps her eyes watchfully on yours while talking, averting them only occasionally to take a hasty glance at the articles about her, she’s a person to be watched. It doesn’t make any difference how handsomely she’s dressed, or whose wife she is, we have to keep an eye on her. Of course, we never let them know we suspect them, but it is seldom they get away with anything when once we have marked them thus. When we once catch them, we generally take them up stairs and search them, and having settled the thing upon them, we make them pay for what they took and warn them never to come in the store again. I suppose there are a great many whom we never catch. But our girls are trained to be quick and clever, and they are not apt to let anyone get ahead of them. Some of them it would be next to impossible for anyone to steal from—they are always watching, and never seem to be. Girls of this kind are, of course, in great demand, and their wages are regulated by their cleverness. There’s a girl,” he added, pointing to a pretty strawberry blonde with a pretty, bright face. “She’s the sharpest girl in the store. She’s always pleasant with the customers, never appearing to be suspicious or watchful, but there is very little she does not see.

A very stylishly dressed lady—the wife of a navy officer—came in here the other day. She had every mark of a lady about her, and was the last person in the world you would suspect of being a shoplifter. But she had not been in the store long, looking over a pile of fine collars, when that girl gave me a sign and told me that customer had something in her pocket that she had not bought. Before we could secure her, she got out of the store, but we followed her close without attracting her attention, and she went into the store next door, and taking the collar out of her pocket, pretended she wanted to match it, then asked the clerk to wrap it up. Just then she was told that she was wanted in here, and she returned without protest, but before doing so she slipped the collar over to her maid, who was accompanying her. They were both brought in here, and she paid for the collar after receiving a lecture, and being warned not to come into the store again. She is a woman of high social position, but is probably pretty well known by the merchants of the city by this time. There are any number of just such cases, though, of course, the majority of the shoplifters are professionals. One woman, who is pretty well known to us now (she lives in a fine house), stole a pair of stockings. The sales girl saw her tuck them up under her basque, and invited her up stairs, and on her way up, she tried to throw them away. There are lots of these cases, and it is hard to tell what to do. I suppose we should expose them, but a great many of them are from families who would be crushed by an exposure of anything of the kind. Then, too, the articles are too small to prosecute for, and we prefer to settle the matter at once. Whenever we catch any one stealing, no matter who it is, we settle with her and show her out.”6

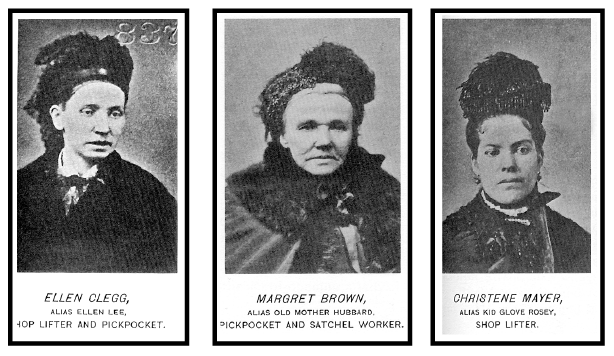

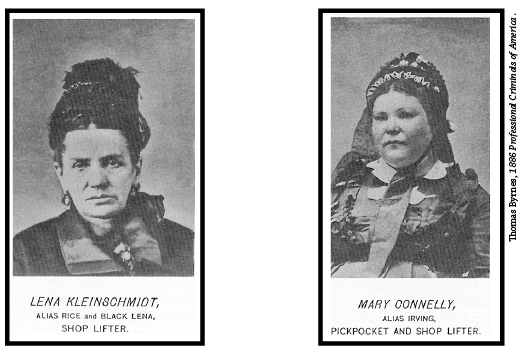

As far as our store manager is concerned, the kleptomania is more fad than affliction, and the only difference between the kleptomaniac and a common shoplifter are her amateur status and family connections. Certainly, some of the professionals are hard to recognize at first sight: a quick glance at New York Chief Inspector Thomas Byrnes’ Rogues Gallery (an 1886 collection of mug shots circulated nationwide) turns up several women who could pass for someone’s unimpeachable Aunt Fannie or fashionable Cousin Florence, were their names not followed by AKAs such as Old Mother Hubbard, Black Lena, or Kid Glove Rosey. They were professionals, however, and frequently worked in pairs, later fencing their goods at a tidy profit.

Byrnes’ explanation for the preponderance of females in the trade would make the blood of any feminist boil:

The work of shoplifting is comparatively easy, it is sometimes remunerative, and above all it is congenial. There are few ladies to whom the visitation of the shops and the handling of the wares are not joys which transcend all others on earth. And the female shoplifter has that touch of nature left in her which makes a clothing store, variety bazaar, or jewelry establishment the most delightful spot to exercise her cunning.7

Almost as an afterthought comes a simpler and more persuasive explanation: a lady’s clothing could hold more than could a gentleman’s. A lady’s garment contained acres of fabric standing at the ready to swallow up stolen goods into cleverly contrived hidden pockets, while a gentleman’s pockets were soon filled. Mother Hubbard went a-thieving in a floor length cloak, and a close look at her sisters in crime will reveal a taste for expansive sleeves and shawls. One lady in dolman sleeves was discovered by the simple expedient of a slight upwards pressure upon one arm, upon which nearly $200 worth of bonnets spilled out upon the ground.8

There are, of course, no kleptomaniacs featured in Chief Inspector Byrnes’ Rogues Gallery, but he distinguishes thus between the professional thief and the kleptomaniac:

The shoplifter is always a person of fair apparel and she generally has a comfortable home. If she be a professional she may be one of a criminal community and her home may be shared by some other engaged in equally evil ways. If she be a kleptomaniac—and in shoplifting the word has peculiar significance—she is possibly a woman whose life in other respects is exemplary. It does seem strange that a wife and mother whose home is an honest one, who attends religious service regularly, and who seems far removed from the world of crime, should be so carried away by her admiration for some trinket or knickknack as to risk home, honor, everything to secure it.9

Byrnes continues by painting a scene straight out of melodrama of the woman tempted, fallen, caught, and shamed. Her absence from the Rogue’s Gallery, however, and his vagary about tangible consequences beyond shame seem to indicate the same double standard as that practiced in Washington.

So, the question arises should there be a double standard? This is where the doctors step in to sharpen the distinction between common shoplifter and true kleptomaniac. The first definition of the disorder comes from Andre Mathey in 1816:

A unique madness characterized by the tendency to steal without motive and without necessity. The tendency to steal is permanent and is not at all accompanied by mental alienation; reason preserves its domain, it resists this secret compulsion; but the thieving tendency triumphs, it subjugates the will.10

This definition has changed little over time. It has only become more comprehensive. The most recent criteria for the disorder comes from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of 2000:

The essential feature of kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal items even though the items are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. The individual experiences a rising subjective sense of tension before the theft, and feels pleasure, gratification or relief when committing the theft. . . . The objects are stolen despite the fact that they are of little use to the individual, who could have afforded to pay for them, and often gives them away or discards them. Occasionally the individual may hoard the stolen objects. . . . Individuals with kleptomania . . . are aware that the act is wrong and senseless.11

By definition, true kleptomaniacs are not tempted by the items themselves, but by the action of taking them. This clinical definition, then, fairly squelches the department store theory of temptation. It is not the goods they are after; it is the experience. Probably kleptomaniacs existed long before they were named—department stores simply outed them. Before that time, families probably quietly returned the little bibelots filched by the Aunt Georginas of the world, and when the families failed to detect the swag, the neighbors’ maids undoubtedly got the sack. It was up to the department store detectives and ambitious shop girls to bring these larcenous tendencies to the attention of the psychological profession and the public.

The only problem was, once they had it defined, what were they to do with it? The best they could do was analyze it, and that did very little good. The earliest theories of cause were not particularly convincing or helpful. These include such terms as “lesion of the will” (the first theory), hysteria, epilepsy, menstruation or its older cousin menopause, stupidity (their words, not mine), penis envy or fear of castration of an imagined penis, and our old friend “department store atmospherics.”12

The Freudians gamely stepped forward to explain the uselessness of many of the stolen objects: the items must be symbolic of something else, usually genitalia. According to psychoanalyst Dr. Emil Gutheil, “Often, the act of theft in cases of kleptomania substitutes for a forbidden sexual act—often incest.” He also connected the compulsion to murderous impulses.13

Wilhelm Stekel, like Freud, attached symbolic meaning to stolen items and regarded the thefts themselves as “expressions of disturbed mental states that arose from frustrated sexual desires.” Stekel’s reasoning was that “Every compulsion in psychic life is brought about by suppression.” Stekel’s 1911 interpretation is still alive and kicking today, with some evidence to support it.14

In 1987, Fishbain cites a case of an otherwise frigid woman, G.Z., achieving orgasm for the first time during her first apprehension for shoplifting. It goes without saying that G.Z.’s crime wave had only just begun. Levity aside, G.Z. had plenty of other problems. She took up shoplifting shortly before a shotgun wedding at the age of twenty: “This behavior was triggered by her being on edge, not knowing what she wanted, and having the urge to run away from an oppressive situation, i. e., the pregnancy and marriage, which, she felt, had been forced upon her.”15

The case of G.Z. leads to the most recent view of kleptomania, that it is related to impulse disorders and driven ultimately by depression and anxiety. The description of the building tension in kleptomaniacs holds a startling resemblance to a panic attack.

Probably the longest kleptomaniac career on record is that of Gretchen Grimm, who began by stealing lipstick at the age of six and ended when she kicked the habit in 2001, at the age of 83:

The only daughter in a family of seven older sons, Grimm felt overlooked and began stealing, she believes, to win her mother’s attention and affection. . . . Over the intervening years, while she raised five children and worked as a nurse at the University of Iowa, she stole, by her own account, “clothes, jewelry, toilet paper, towels, pencils, pieces of stone—everything.” At the moment of theft, she says, “you feel wonderful, elated, slick and cool and cunning.” But immediately afterward, guilt would set in, and often she would actually sneak her loot back into the stores.16

Grimm was cured by a combination of psychotherapy and Paxil. G. Z. was likewise treated by a combination of antidepressants and behavior modification.

An anonymous contributor to Newsweek’s 2003 “What it Feels Like” column provides an additional dimension:

I didn’t steal because I was destitute. I stole because I had different emotions—fear, anger, frustration, and desperation—all banging up against one another. Shoplifting became the release, and the release became an addiction. I felt entitled to shoplift because I felt that I had suffered unfairly in my life and that stealing redressed these wrongs. Let someone else be the victim.17

Did Anonymous fit the definition? Yes. She confessed that she maintained a twelve by twenty foot storage room filled with things she would never use. But the entitlement claim is a disturbing one that echoes outraged shopkeepers from the last century: What about accountability? We will return to this thorny issue.

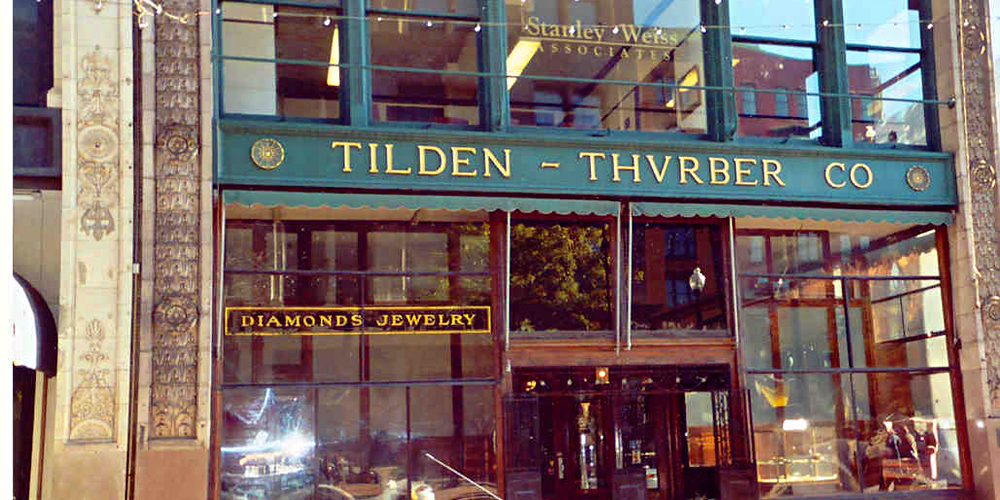

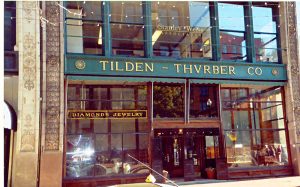

Having done a brief survey of the kleptomania field, it is time to see whether Lizzie was out standing in it. Her reputation rests upon only two specific events: the daylight robbery of 92 Second Street and the theft of two paintings from Tilden-Thurber in Providence, RI. The daylight robbery took place in the summer of 1891, when the parental Bordens were at the Swansea farm and just after a rash of robberies later traced to a young man who possessed a set of “sized” keys.18

According to Captain Desmond’s report found among the Knowlton Papers:

On 2nd floor in a small room on north side of house I found Mr Borden’s desk. It had been broken open. Mr Borden said “$80.00 in money and 25 to 30 dollars in gold, and a large number of H car tickets had been taken. The tickets bore name or signature of Frank Brightman.” Brightman was a former treasurer of Globe St. railroad co. Mrs. Borden said “her gold watch & chain, ladies chain, with slide & tassel attached, some other small trinkets of jewelry, and a red Russia leather pocket-book containing a lock of hair had been taken. I prize the watch very much, and I wish & hope that you can get it; but I have a feeling that you never will.” Nothing but the property of Mr & Mrs Borden reported as missing.

The family was at a loss to see how any person could get in, and out without somebody seeing them. Lizzie Borden said “the cellar door was open, and someone might have come in that way.” I visited all the adjoining houses, including the Mrs Churchills house on the north, Dr Kelly’s house on the south, Dr Gibbs house & Dr Chagnon’s house on the east, and made a thorough search of the neighborhood to find some person who might have seen someone going, or coming from Mr Borden’s house; but I failed to find any trace.

I did get a 6 or 8 penny nail which “Lizzie Borden said she found in the Key hole of door,” leading to a sleeping room on 2nd floor, east end of building. So far as I know this robbery has never been solved.

P.S. Mr Borden told me three times within two weeks after the robbery in these words “I am afraid the police will not be able to find the real thief.”19

In addition to the suspicious circumstances surrounding that crime, there is this report from the New Bedford Evening Standard that Chief Hilliard, allegedly, testified at the grand jury that Mrs. Borden was missing free horse (car) tickets and that when persons were found using these tickets, and questioned, these people replied “Lizzie Borden gave them to them.”20 If this report is true, the assumption of Lizzie’s guilt of theft almost becomes a certainty.

The second incident took place five years later at the Tilden-Thurber store in Providence, RI. Two porcelain pictures stolen from the store were traced to Lizzie and the affair was privately settled out of court. (A rumor that she purchased her freedom with a signed confession was circulated, many years later, and then debunked.) At least one of the pictures, like the horse car tickets, had been given away to a friend.

The second incident took place five years later at the Tilden-Thurber store in Providence, RI. Two porcelain pictures stolen from the store were traced to Lizzie and the affair was privately settled out of court. (A rumor that she purchased her freedom with a signed confession was circulated, many years later, and then debunked.) At least one of the pictures, like the horse car tickets, had been given away to a friend.

Three further charges remain, though these are hearsay. The first is a piece that appeared in the 1899 Fall River Evening News: “A rumor has been widely circulated within the past 24 hours that the Pinkerton detectives have been shadowing Miss Borden on suspicion that she has been shop-lifting in Boston.” More impressive, if less specific, evidence comes from a 1992 statement made by the grandson of Andrew Jennings who said unequivocally “Lizzie was a chronic shoplifter.” Lastly, in an interview with the Hartford Courant in 1971, Mrs. Ellis Gifford, curator of the Fall River Historical Society, stated that she knew Lizzie to be a kleptomaniac. Her husband owned Gifford’s Jewelry Store in Fall River. Mr. Gifford, she said, “watched Lizzie ‘very carefully’ when she came to the store. . . . the clerks would watch her carefully if my husband was busy. She had plenty of money to buy everything she wanted. It was a compulsion.”21

However, even if Lizzie committed all the thefts, did that make her a kleptomaniac? After all, though all kleptomaniacs are thieves, not all thieves are kleptomaniacs.

The cash and gold said by the Knowlton Papers to be missing seem to be uncharacteristic of kleptomaniac behavior. Unlike the purse, lock of hair, watch, and tickets, the former missing items had value and were untraceable. While we do not know what became of them, it is possible that she hoarded the personal items for a time, and then returned them. Any shoplifting done after the murders would fit the criteria admirably. By then, she was wealthy and no longer hampered by family frugality. There would have been no temptation by the objects, only by the act. However, would it be the act of a kleptomaniac or the act of a bored middle-aged woman?

Lizzie Borden may indeed fit the profile of a kleptomaniac. Before the murders, she lived in what some have deemed oppressive circumstances on Second Street. The company at home was far from congenial, and the path allowed her was a narrow one. Very much like G.Z., she was in a powerless situation, where she led a life that she plainly felt had been “forced upon her.”

Some believe that both the Borden daughters felt a keen sense of injury and neglect by Andrew—over Abby’s landholdings and Andrew’s own stinginess towards them. As Murray remarked, kleptomaniacs “often had experienced separation from parents and open dislike from their fathers. Children also might steal to get even with their fathers.”22 The girls lost their mother, Sarah, at an early age, and though most of their resentment was directed towards Abby, it is likely that they held a great deal bottled up in reserve for Andrew, who was the driving force of the household. Andrew is believed to have doted upon Lizzie, but the evidence for that affection is rather slim: a ring on the little finger and a trip to Europe in 1890. More memorable might be the message sent by the placement of his bedroom key on the mantel as a subtle reminder of cold warfare. We do not know when that started, but might it have been a tactic used by him habitually? In a household of covert battles, the passive aggressive act of shoplifting would have done admirably to “get even” with Andrew.

Last of all, Lizzie very possibly had the chief hallmark of the kleptomaniac—depressive episodes. Although far more socially inclined than Emma, Lizzie could also be withdrawn in the extreme, spending the day in her room. She was generally reclusive in her years at Maplecroft and slept poorly, as the letter to her neighbor about the “little bird” attests. It seems likely that she suffered from some form of chronic depression.

If the line had run, “Lizzie Borden took a Paxil,” could she have overcome the shoplifting urge—and, assuming she was guilty, the urge to do murder as well? One common thread seems to run through kleptomania cases: a sense of entitlement. The popular approach has been to enable and excuse the acts of kleptomaniacs. This is not to say that they should have been run out of town on a rail, but they were given no means or incentive to reform. Did “the girl can’t help it” view inspire Lizzie and give her the (correct) notion that no jury of twelve good men would convict her? As Murray says, “The motivation behind kleptomania was expected to be complex.” Even if Lizzie was a kleptomaniac murderess, we should regard her as a complex individual. Her motives and actions, so often reduced to simple greed, may hold volumes that we can never read.

Endnotes

1 Elaine S. Abelson, When Ladies Go A-thieving: Middle Class Shoplifters in the Victorian Department Store (NY: Oxford University Press, 1989), 8.

2 Ronald A. Fullerton and Girish Punj, “Shoplifting as Moral Insanity: Historical Perspectives on Kleptomania,” Journal of Macromarketing (I:8, June 2004): 10.

3 Abelson 6.

4 Fullerton 10.

5 John B. Murray, “Kleptomania: A Review of the Research,” The Journal of Psychology (Vol. 126, #2, March 1992): 132.

6 Ironically, the rest of the page is covered with ads for furniture, apparel, and other goods offered on the corner of Pearl and Main.

7 Thomas Byrnes, 1886 Professional Criminals of America (NY: The Lyons Press, 2000), 30.

8 Ibid. 31.

9 Ibid. 31.

10 Fullerton 14.

11 Ibid. 15.

12 Ibid. 11, 13.

13 Ed Sams, Lizzie Borden Unlocked, (CA: Yellow Tulip Press, 2003), 61.

14 Fullerton, 12.

15 David A. Fishbain, “Kleptomania as Risk-Taking Behavior in Response to Depression,” American Journal of Psychotherapy (XLI, 4, Oct 1987): 599.

16 Jerry Adler, “The ‘Thrill’ of Theft,” Newsweek (25 February 2002): 53.

17 Anonymous, “What it Feels Like to be a Kleptomaniac,” Newsweek (August 2003): 2.

18 Leonard Rebello, Lizzie Borden: Past and Present (Fall River, MA: Al-Zach Press, 1999), 36.

19 Michael Martins and Dennis A. Binette, eds., Commonwealth of Massachusetts VS. Lizzie A. Borden; The Knowlton Papers, 1892-1893 (Fall River, MA: Fall River Historical Society, 1994), 74-75. “Note: ‘Capt. Desmonde’ and ‘Robbery Case’ handwritten in lead and ink respectively on reverse side of document.”

20 Rebello 36-37.

21 Ibid. 304-306, 500.

22 Murray 133.