by Mary Elizabeth Naugle

First published in August/September, 2004, Volume 1, Issue 4, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Lizzie Borden took an ax

And gave her mother forty whacks.

When she saw what she had done

She gave her father forty-one.

There’s nothing like a good juicy murder to bring out the comedian in someone and a willing audience in everybody else. So it is now, so it was in 1892, and so it has been since time immemorial—and that comedian may still have his baby teeth or may be toothless with age. We cannot blame gallows humor on the times, for it is timeless, possibly reaching back to the Dark Ages when children first chanted “Ring around the rosy/a pocket full of posy/ashes, ashes, we all fall down,” collapsing on the ground in fits of laughter while the Black Death mowed down those mimicked by the circle. Granted, this example is not associated with murder; still, the specter was gruesome as any Bluebeard and it was a startling subject for a child’s game. Some dispute the age and interpretation of the rhyme, saying it cannot be found in print before 1882 (Baring-Gould 252), but it has the sound of something much older and may have been a late recording of a more ancient oral tradition.

The date and meaning of the following rhyme, from Gammer Gurton’s Garland 1784, is unmistakable, however:

On looking up, on looking down,

She saw a man upon the ground;

And from his nose unto his chin,

The worms crawled out, the worms crawl’d in

(Baring-Gould 88).

The rhyme has persisted in many incarnations to this day, intended to induce a shiver and make Death an object of fun. But if we must have a murder rhyme predating the famous Lizzie ditty, here is the classic rhyme commemorating the exploits of Burke and Hare in 1828 Edinborough:

Up the close and doun the stair,

But and ben wi’ Burke and Hare.

Burke’s the butcher, Hare’s the thief,

Knox the boy that buys the beef

(Roughead, 169).

Burke and Hare were resurrection men (read “grave robbers”) who sold fresh specimens to Dr. Knox, who used them for dissection in anatomy class. When specimens were in short supply, Burke and Hare manufactured their own for a none-too-fussy Knox.

Little has changed since then. “Geiners,” limericks and jokes about Ed Gein (the people pickling inspiration for Norman Bates and Hannibal Lechter), were great favorites in Wisconsin and beyond in the late 1950s. A sample Geiner: Why did Ed Gein crank up the heat? Because the furniture had goosebumps. In the 1980s, David Hendricks was found guilty (later reprieved) of dismembering his family (with an axe, by the way) in Bloomington, Illinois. When the upscale suburban home went on the market, this joke hit the streets the same day: “I hear they’re selling the Hendricks house—they’re asking an arm and a leg.” I know. I was there to hear it—and to pass it on. And today we buy and sell bobble-headed Lizzie dolls.

We all whistle in the dark at times, telling others and ourselves that we are not afraid. Some will whistle hymns when passing graveyards. Others show bravado by laughing like a comic book hero in the face of danger. J. K. Rowling uses it in Prisoner of Azkaban, the latest of the Harry Potter series to hit the big screen, by having the defense against the boggarts (who embody fear itself) be an absurd thought accompanied by the incantation “Riddikulus” (Rowling 135).

Fall River seems to have felt that need from the start. The Lizzie Borden Sourcebook prints a band concert program from the August 8 Fall River Globe with the added heading, “A Prophetic Musicale?” The prophecy revolves around the first number of the evening, “Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom-De-a” (50). I suspect the number was less prophecy than inspiration for some wag needing to shake off the chill of that night’s walk home. That evening many would have been troubled by each shadow that might prove to be the killer. What a comfort the lighthearted tune would have been, whistled to summon visions no more sinister than the can-can and naughty postcards. Add to the tune the nose-thumbing lyric and our young blade assumes a careless pose, assuring us (and himself) that this crime was a family affair and presents no threat to him or to anyone else.

Although the Ta-ra-ra-parody is the only bit of wit to pass on into posterity, two of several club sendups were given press the summer of the trial. The first was staged by the Lizzie Borden Club, fifty strong, who gathered for their first meeting at the Germania Club in New Bedford “To promote the cause of temperance, but at the same time to oppose the so-called prohibition movement of today” (Rebello 266). This conundrum was compatible with the equally unlikely picture of Lizzie Borden as an axe wielding member of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union—unless that axe was to be wielded, Carrie Nation style, against kegs of demon rum. Emma had her supporters as well. A representative of the Emma Borden Club of Brockton was in attendance to present the fledgling drinking club

with a hatchet so formidable in appearance as to unnerve any ordinary man. The blade is nine inches long and five inches wide. It has a handle as large as that of a pick axe and has a peculiar slanting construction at the head which gives it an appearance vastly different from any other instrument of the kind. It has a saw-like edge and has a number of stains on either side of the blade which the members claim to be blood. . . . new members . . . would be obliged to kneel on the floor while one of the officers of the association placed the edge of the hatchet in 13 different positions on his skull. The initiated member would then be obliged to clean the edge of the instrument with his handkerchief and then burn the handkerchief (266).

The ceremonial positioning of the absurdly shaped oversized hatchet provides a macabre echo of the expert witnesses’ attempts to fit the handleless hatchet head to the Borden crania. What better way to erase that ghastly scene than by replaying it in burlesque: one man posturing as a self important expert making the most of his fifteen minutes of fame, the other making preposterous faces for the crowd—perhaps even dropping his head to the floor as another young man throws up his hands, giving a falsetto cry, and swooning. And that crowd, against its better inclination, laughs until the tears run down its cheeks. After the tension of the courtroom they can do so at last. Perhaps full catharsis requires laughter in addition to pity and fear.

The Borden Club’s final target? The verdict. They cancel any doubts concerning its wisdom by parodying its pronouncement in the club’s oath: “I believe that the person who committed the horrible deed was under the influence of liquor and that a masculine hand struck the death blows.” The club password? “Not guilty” (266). The bitterness they clearly feel is drowned in liquor and levity.

It took Fall River less than a month to follow suit, this time by rededicating a pre-existing club, The Fall River Wheelmen (see note). This story, from the Fall River Daily Herald of August 2, is printed in Rebello (271 & 268). The Herald takes a dimmer view of its homeboys than does the Journal:

A company of young men with reputed good sense have entered into a conspiracy against the fair name of the city. It was a thoughtless movement at the start, and citizens who have the good reputation of Fall River at heart hope that they will abandon the idea when the foolishness is pointed out. It happened this way:

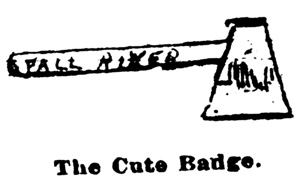

The enthusiastic bicyclers who recently attended the convention of the Massachusetts division of wheelmen at Cottage City wanted some sign which should be peculiar to Fall River riders. By an inconceivable method of reasoning—or, more probably, without any reasoning at all—it appeared to somebody that an axe, suitably inscribed, would be a cute little badge for the Fall River wheelmen. Acting upon this idea, some of the riders had a pin made of silver, and wore it on their uniforms. It was something like this:

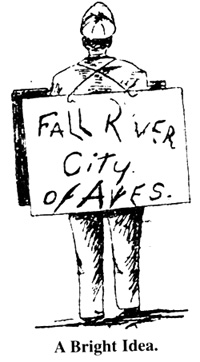

Not content with this inconspicuous souvenir, the Fall River riders bore a banner in the parade that was inscribed thus:

The article goes on to describe the oafish behavior of the Fall River fellas who “laughed and waved their hats whenever anybody pointed at the symbol of a gory weapon. . . . They thought it was a great joke to picture the dripping blood and to impress upon the minds of hundreds of spectators who had never visited the city that they must look out for harrowing experiences if they ever came within these borders” (268).

When scolded, the Wheelmen maintained “that the axe was only a symbol of victory—cutting down the claims of adversaries in the contests of skill or endurance” (268).

Right.

Adding insult to injury, some had taken to donning “the silver axes, trophies of the tournament . . . to wear on their weekly excursions to other cities . . .” thus keeping the story fresh in the minds of the public.

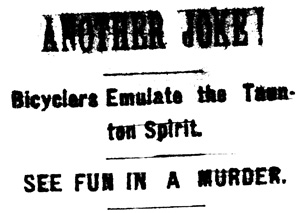

Interestingly, one gathers from the headline that the Wheelmen were imitating yet another group in Taunton, lost to the annals of time:

We can only guess at the nature or reception of the Taunton bunch. But the Wheelmen get a decidedly poor review. This rejection may be due to civic pride or to the general tastelessness of taking “City of Axes” banners on the road. Perhaps the Herald is just a classier publication. But, much as I’d give for a cute hatchet pin, I can’t help thinking that the Borden Club has good press because its jokes are better. It’s like pitting Hasty Pudding against a high school key club skit. I wonder if the Herald reporter, upon viewing the wheelmen’s antics, longed to adjourn to the Germania Club in New Bedford. After all, the Borden Club was anything but dry.

NOTE: Some may wonder along with me if David Anthony, a great one for cycling, was among this band of merry men. If so, and if he was, as some claim, the real killer, he was not only a murderer but also the greatest cad who ever lived.

Works Cited:

Baring-Gould, William S. and Ceil Baring-Gould. The Annotated Mother Goose. NY: New American Library, 1972.

Kent, David. The Lizzie Borden Sourcebook. Boston: Branden Publishing Company, 1992.

Rebello, Len. Lizzie Borden: Past and Present. Fall River: Al-Zach Press, 1999.

Roughead, William. The Murderer’s Companion. NY: The Press of the Readers Club, 1941.

Rowling, J. K. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. NY: Scholastic Inc., 1999.

Images courtesy of Len Rebello.