by Kat Koorey

First published in December/January, 2004-2005, Volume 1, Issue 6, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

The Cellar

The smell of damp earth seeps up the steps, but it’s not the sense of graves I get—it is the wholesome odor of good loam, of growing things, not dying things.

When the cellar door opened, I found the soul of the house. If the sitting room was the business heart of Andrew’s house, the cellar was the spirit, the soul, and the foundation. Maybe that is why Emma claimed she had not much reason to ever go down there—Emma was no longer growing? Maybe her spirit was sucked dry by 1892.

The steps go steeply down and in 1892 there would have been a dirt floor except for the raised walk of boards to the water closet and some bricking of the floor in the laundry room. Why did Emma deny the cellar? Lizzie was very open about its use. Emma seemed to want us to think she didn’t even know what was down there—axes, hatchets, or anything until reminded. “I had nothing to go for” (Inquest 110).

When we first saw the cellar in March of 2004, there were decades of things stored all around which gave a sense of a lowering cave and made it seem maze-like. Our repeat visit in October showed us a cleaned up relic with lots of room and because of this the floor plan was more easily ascertained. Of course, in Lizzie’s day, that basement area probably was crammed with all the things Andrew didn’t want to part with, including old business records of his partnership with William Almy. Apparently it was a Fall River habit when someone retired from business to move the records to the cellar or attic for storage, maybe never even looked at again. The FRHS has seen records like these from families cleaning house from 100 years ago. It’s amazing to wonder at whatever happened to the Borden & Almy business files! Meanwhile, those long-ago searchers could easily be confused by the layout, if the place was stuffed with the residue of Borden life there accumulated after 20 years.

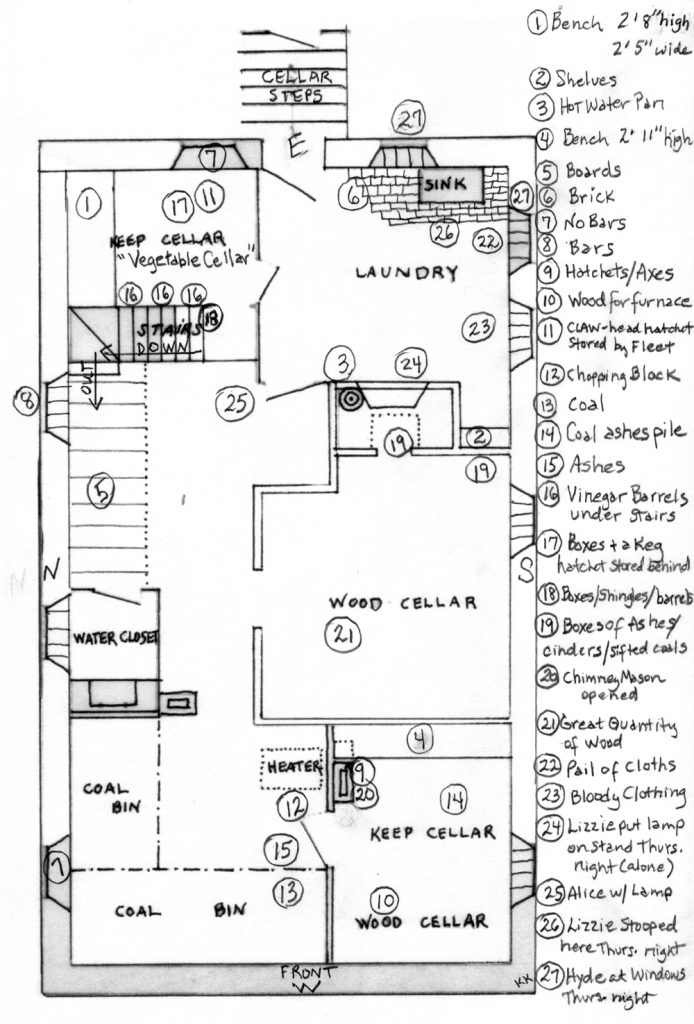

As one enters out into the main cellar from the interior house steps, the floor plan is simple enough. Straight ahead on the right half of the room is where the privy closet was situated, behind which were located the coal bins. There is a dark gray area on the north wall that designates where the old water closet stood. The area around this has been whitewashed over time, so the unpainted section is obvious. It was vented by the window right above, and also by a pipe that traversed the house up to the roof, and was served by flushing water. It was a rectangular structure that faced the stairs and stood out maybe 8 feet in length from the wall, it’s form, and the walkway to it, creating a sort of “alley-way” in the main middle part of the cellar. Behind it, against the remainder of the north wall on the right, and part of the west wall in the rear of the cellar by the street, was where coal storage bins used to be situated. The furnace also stood in this rear main area, on the left, against the chimney barrier which comprised a wall of the last southwest cellar room near the street. This is the chimney where the axes and hatchets were found, pointed out by Bridget.

Again, as one enters, directly to the left is a wall, around which one would find the vegetable cellar and the area for storage of Andrew’s vinegar barrels, under the stairs one has just descended. Directly left, and across from this room, on the south (or Dr. Kelly side), is the washroom where there was a sink against the rear east wall that was Bridget’s laundry area. The current laundry facility is now opposite, in the “vegetable cellar” room. The rear cellar door to the outside is here between these two rooms: what the police called a “bulkhead”—a large, stout door with several locks, apparently original, which opens into the room, and has steep stone steps beyond. These steps would raise one up to ground level outside, where there once was an outer door, built into a little shed-like structure, which would have protected the interior door and cellar from the weather. Thus, there were two doors to the cellar that led to the outside.

There is some discrepancy in the statements of police and civilians as to whether either or both of these doors were locked on Thursday, upon the first search. Assistant Marshal Fleet deposed that the first time he went down the cellar he found the inner door “open,” and the outer door “fastened” by a bolt on its inner side, not too long after 11:45 a.m. (Trial 478). John Morse let it be known that he thought the exterior cellar door was “open” (Preliminary 256). Officer Doherty claimed that he tried the interior cellar door to the outside and found it “locked” (Preliminary 332). The outer cellar door was tried and found fastened by Stevens, according to Manning who was with him, sometime before 11:50 a.m., Thursday forenoon (Trial 1484). Bridget, upon being asked openly on Friday morning, in front of Edson, by an early-rising, newly-orphaned Lizzie, if she had known for a fact that the cellar door had been fastened on Thursday, Bridget answered, “Yes, marm” (Witness Statements 35-36). As long as one of those doors was fastened, an intruder could not enter that way, yet there seems like some family push to leave some doubt as to that fact. With so many conflicting stories of the door, we will never know.

Again, we are returned to standing at the foot of the steps, as we first enter the main cellar, for reference. The other two rooms are off to the left, on the (south) Kelly side of the house and farther west toward the street. One is called the “Wood Cellar” on the Kieran plans—the room that is the center left room, under the sitting room. That room has a doorway style fireplace venting area with hooks above, embedded in the brick. Here is the back of the chimney which goes all the way through to the laundry room fireplace, with many twists and turns and nooks and crannies in between, but on a small scale. Apparently on wet Tuesdays, if Bridget did not want to get behind in her laundry work, she would hang clothes to dry here from those nails above the chimney opening. There is told the story that in the 1840s, when the house was built, Indians could still be a threat on the rampage and one or more of the residents of the house could hide up in there inside the chimney. I hear constantly that “people were smaller then,” but that small? Maybe they stood in there and pulled a cupboard over the opening. That, at least, is possible.

This is the room that is now the office and there now stands a businesslike desk directly under the spot that would correspond to the location of the sitting room sofa on the floor above, and where the production company who made the recent video on the crime had access to spray Luminol there on the ceiling. It no longer glows, but on camera one can see the remnants of possibly the 112-year-old bloodshed of Andrew Borden! Imagine sitting there in the office chair, counting inventory and working on correspondence, knowing the ceiling was glowing with blood last March?

The final area in the cellar that does have direct ties to the trial is the far west room on the south side. The furnace stands sentinel just before the entrance. As one passes that and turns the corner, directly to the left is a whitewashed brick wall with open spaces. This is the chimney where, about six feet above the floor, a box was found with axes and a hatchet. Apparently Bridget showed the searchers this box when requested to do so by Lizzie, who was prostrated upstairs. The box that held the handleless hatchet head was that same box found in a “jog of a chimney.” The box was about “fourteen inches long, perhaps eight or ten inches wide . . . about four inches deep.” Also found there with it “were other tools . . . small tools in there, pieces of iron” (Fleet, Trial 474, see #9 on plan).

Nearby, just outside the entrance to that room, was a chopping block, upon which rested the claw hammer hatchet that was so prominently displayed as the murder weapon in the preliminary hearing (See #12 plan). Fleet took that claw hammer hatchet, “The largest hatchet with the rust stain on it and the red spot upon the handle that apparently had been washed or wiped . . . [and] placed [it] behind some boxes in the cellar adjoining the wash cellar” (Trial 466, see plan #11).

On Saturday the box with the handleless hatchet head was “lying at that time at or near the floor . . . it was on some wood within perhaps a foot of the floor . . . directly under” the shelf upon which it had first been found (Seaver, Trial 742-743).

The four axes and hatchets were taken away early Friday morning, the 5th of August. The handleless hatchet was not removed from the premises until Monday the 8th, by Officer Medley (Edson, Trial 660-661). The second time Mr. Mullaly searched the cellar he showed Fleet the box from which he claims Bridget took “them hatchets.” Fleet removed the hatchet head out of the box, the remarkable handleless hatchet, which at the time appeared to have a clean, fresh break and ashes upon each side of it. When Mullaly dropped his bombshell in court that there was also a handle in that box which he considered corresponded with the break in the little piece which was still in the hatchet head, Fleet’s credibility, and the trial itself, were in jeopardy and changed forever (Trial 617-632). The focus shifted. Knowlton made claim in court that “This is the first time I ever heard of it,” and Fleet was recalled and denied seeing any handle in the box Trial 635).

This contradiction on the stand of prosecutorial witnesses also exploded any speculative impressions left to the jury as to just what, exactly, had once been that cylindrical object, of hatchet-handle length and shape which was supposedly found burned in the stove earlier on Thursday. It couldn’t have been the hatchet handle if one existed in the cellar! Unfortunately, this information was stumbled upon midway through the trial, in June 1893, and no corresponding hatchet handle was ever seen again. Edson and Mahoney, at Knowlton’s request, were dispatched to the Borden house that very day at 3:40 p.m. and through the servant girl sent word to Emma to gain admittance and failed. Knowlton’s plea for one more chance to search the premises was “with no other interest than that of justice.” Mr. Robinson answered in open court, “Justice is what we want.” Of course, it was too late (Trial 640).

The scariest and most horrible night in the history of the Borden girl’s lives must have been the night after the murders when their father and stepmother’s bloody and mutilated bodies, stitched up like Frankenstein’s monsters, lay covered and closed up in the dining room. The smell of fear, the smell of death, the smell of blood must have seeped through the draperies covering the bodies and swelled the noxious fumes under the doors and permeated the rooms on that floor. Blood still spattered the painting above the sofa in the sitting room, the last remnant of the beating of Andrew’s dying heart.

Through this room eerily moved a light. An on-duty cop, outside in the dark on sentinel, watched it’s progress. He noted two women, Lizzie and Alice Russell, who had gallantly stayed the night to succor her friend and give aid in any way she could. It seemed to Joseph Hyde as if they drifted on their way, light aloft held by Alice, through the sitting room, into the kitchen, and he watched as the light reappeared down cellar. He left his post to look in the cellar window: A lonely watch on a lonely murder night, and here, finally, was something to see!

Hyde moved to the southeast corner window and peeked in. He witnessed Alice Russell stop a few feet away from the cellar steps coming from the interior of the house, holding a hand lamp, nervous, hanging back. Lizzie Borden carried a slop pail and proceeded directly to the water closet and dumped the contents and then passed Miss Russell going to the sink in the washroom where she ran some water, rinsing the pail. After this, the ladies returned the way they came, the light floating ahead of them, eerily quiet, until they were safely back upstairs. There hadn’t been a word spoken, though Hyde firmly believed Miss Russell was frightened and almost shaking.

Poor Alice had volunteered to accompany Lizzie to the cellar to light her way. She probably thought she had done Lizzie a service, but then, not fifteen minutes later, while Alice herself was bathing in the Borden bedroom preparatory to bedtime, the light was seen again, drifting down the stairs, through the sitting room, scene of so much carnage, drifting tendrils through the darkened kitchen and down again into that damp pit—a lone girl, no companion, on another errand. It was Lizzie Borden, and while Officer Hyde watched from the other southeast window around the corner, she walked to the west side of the washroom, set her lamp down, moved over to the area in front of the sink and stooped down. “Oh, she wasn’t there a minute,” Hyde later reported, but what did she do? He didn’t see her open the cupboard under the sink. He didn’t see her disturb the pile of bloody clothing that lay several feet from where she was hunkered down. He knew the pail of bloody cloths was below his vantage point, and very near that sink, but he did not see Lizzie do anything. She stooped there and then she straightened, picked up her light and returned upstairs, alone, through the dark hall, the kitchen, the bloody sitting room, past the dining room closed up ugly like a tomb, through the front foyer and up the front stairs to her room, and Alice never knew of it, Lizzie’s solo expedition to the bowels of that house, until Hyde told her of it, Monday, August 8th (Trial 847, Witness Statements 39).

This uncommonly secretive act rivals only the dress burning incident in its naïve audacity. What could bring Lizzie down to the cellar washroom twice in fifteen minutes, enduring that long journey four times through the scene of Andrew’s murder, on the most horrifying night of her life? A clandestine visit which purpose Lizzie seems to have hidden from her friend. By this time the Borden bedroom door had been opened, though Lizzie had replaced the hook on her side. She could have gone through that bedroom where Alice was staying that night, if she had no secret reason for stealth. And yet she took a light, which someone stationed outside was bound to notice, lighting her way as surely as an actor in the spotlight on a stage.

Prosecutor Knowlton’s closing argument concerned this cellar trip into the mysterious alcoves of the soul of this house. He is incredulous at this seemingly fearless nocturnal walk of the enigmatic Lizzie: “I do not care to allude to the visit to the cellar; I do not care to allude to her remarkable coolness of demeanor to the officers in the afternoon. She is certainly a remarkable woman: she is certainly a remarkable woman. Some people may share with me that dread of going down below the stairs into the somewhat damp and gloomy recesses of the cellar after dark. I should not want to confess myself timid, but there have been times when I did not like to do it. And all the use I propose to make of that incident is to emphasize from it the almost stoical nerve of a woman, who, when her friend, not the daughter nor the stepdaughter of these murdered people, but her friend, -—could not bear to go into the room where those clothes were, should have the nerve to go down there alone, alone, and calmly enter the room for some purpose that I do not [know] what connection it had with this case” (Trial 1836).

The cellar was a utilitarian stronghold; a safe place to hide in case of Indian attack; several fireplaces could be utilized for heat and cooking under siege; the water closet was positioned there to carry away the human waste as the by-product of the Borden menu; the laundry sink and hot water pan were there to wash away the stains of eating and living in that house; the vegetable cellar stored barrels of vinegar and probably had stored root foods at times; the sink provided running water; a bulkhead door led outside to lawn and sun and pear tree. A person could live there if necessary – it truly was the soul of 92 Second Street, with that dark, sweet breath of good loam and growing things, and not of graves.

Footnotes:

1 Commonwealth of Massachusetts VS. Lizzie A. Borden; The Knowlton Papers, 1892-1893. Eds. Michael Martins and Dennis A. Binette. Fall River, MA: Fall River Historical Society, 1994. Floor plan, cellar, page 133, “Trial Exhibit #8.”

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Preliminary Hearing in the Borden Case before Judge Blaisdell, August 25 through September 1, 1892. Fall River, MA: Fall River Historical Society. Pages 339 and 348.

6 Ibid, pages 351 and 357.

7 Burt, Frank H. The Trial of Lizzie A. Borden. Upon an indictment charging her with the murders of Abby Durfee Borden and Andrew Jackson Borden. Before the Superior Court for the County of Bristol. Presiding, C.J. Mason, J.J. Blodgett, and J.J. Dewey. Official stenographic report by Frank H. Burt (New Bedford, MA., 1893, 2 volumes). Page 842.

8 Ibid.

9 Trial, 332 and 333.

10 Ibid.

11 Trial, 466.

12 Trial, 507 and 572.

13 Trial, 508 to 511.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Trial, 511.

17 Ibid.

18 Trial, 657.

19 Trial, 658 and 659.

20 Trial, 662 and 663.

21 Preliminary Hearing, 424.

22 Trial, 847.

23 Trial, 844 and 845.

24 Trial, 845.

25 Trial, 840.

26 Trial, 845.

27 Trial, 844 – 847.