by Shelley Dziedzic

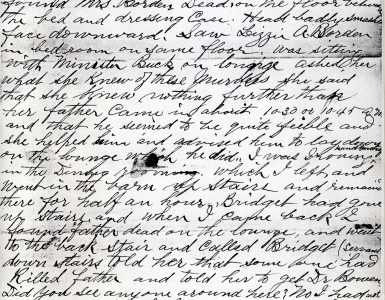

First published in November/December, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 4, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

The 27-year-old face that gazes earnestly above the tightly buttoned, notched lapels has a beseeching look. Other than a few courtroom sketches, this portrait is how most people who study the Borden murder case recall Eli Bence, the clerk at D.R. Smith’s apothecary on Columbia Street at the corner of South Main: a stubble of bristly hair, neat mustache, and a steady gaze. Other than Alice Russell and her damaging testimony about the dress that Lizzie Borden burned in the kitchen wood stove after breakfast on the day after her parents’ funeral, perhaps no other single individual possessed such potentially lethal information, which, if it had been allowed, might have changed the course of events for Lizzie Borden.

The 27-year-old face that gazes earnestly above the tightly buttoned, notched lapels has a beseeching look. Other than a few courtroom sketches, this portrait is how most people who study the Borden murder case recall Eli Bence, the clerk at D.R. Smith’s apothecary on Columbia Street at the corner of South Main: a stubble of bristly hair, neat mustache, and a steady gaze. Other than Alice Russell and her damaging testimony about the dress that Lizzie Borden burned in the kitchen wood stove after breakfast on the day after her parents’ funeral, perhaps no other single individual possessed such potentially lethal information, which, if it had been allowed, might have changed the course of events for Lizzie Borden.

Fortune smiled on the defendant when Mr. Bence’s testimony of what he had seen and heard was disallowed at the trial, on June 14, 1893, of Lizzie Borden for the murder of her father and stepmother.

Inasmuch as no poison had been found in either of the Bordens’ stomachs, and that Lizzie’s alleged visit to D.R. Smith’s drug store on the morning of August 3 was deemed by the court as inadmissible, Bence’s testimony was adjudged irrelevant in the end. Eli Bence’s thoughts, upon hearing this, can only be imagined. In 1892 Fall River, and indeed in today’s society, many were and are more than a bit hesitant to come forward and become involved in criminal investigations for reasons stemming from lost time on the job, to a reluctance to be interviewed by police and newspaper reporters. In such a high profile case, Bence must have drawn upon a deeply ingrained sense of civic responsibility and duty to put himself willingly and unsparingly in the bright glare of what would be known as the Crime of the Century. Under oath, he put his name and career on the line by taking on the daughter of one of Fall River’s influential businessmen—and a Borden. He was but a young clerk with his living to earn, with a young wife and 3-year-old son to provide for. Whether he enjoyed the support of his employer, family, and spouse in coming forward to testify is uncertain, but what is known is that his involvement in the Borden trial would follow him the rest of his life, right onto the front page of the New Bedford newspaper with his obituary at his death in 1915 in his 50th year. What made the character of such a man as Eli Bence?

Bence was not a stranger to death, tragedy, or hard work. Eli’s father, William Bence, was from the country town of Heaton Norris in Lancashire, England. His first marriage was in 1848 to Ann Gaskell of Disley, Cheshire. They had a son, Peter Gaskell Bence, born in 1849. In 1853, Ann died and was buried in Love Lane, Heaton Norris, with her little daughter, Emma Bence, who died the day of her birth in 1852. William Bence would not remain a widower for very long.

On the day after Christmas 1853, in the Chapel of Saint Thomas, William married Sarah Hudson, a girl from Cheadle Buckley, Stockport, Cheshire, England. Sarah produced a son, Horatio, in 1854, but the couple’s happiness quickly turned to sorrow when the little infant son died within the year. Soon after, the couple set sail for Tiverton with Peter Gaskell Bence, moving just on the outskirts of Fall River. It was there where John William Bence was born the year after Horatio was laid to rest in the English soil. John William married Harriet Fields in 1883 and produced one little daughter, Mabel G. Bence. They settled in Swansea.

By 1858, Edwin Bence had arrived, and the family was living in Fall River, with father William Bence turning a deft hand to many tasks to support his growing family. The little boy, Edwin, died at age 4 in 1862 as the Civil War raged on. The first daughter, Sarah Jane, was born the same year as Lizzie Borden—1860. Sarah Jane would become a schoolteacher in Fall River, marry Mr. Robert Goff of Swansea, and produce a happy family of three children. The Bence’s second daughter, Mary Hannah, was born just after Edwin died in 1862, and passed away only nine months later.

In 1864, the Bence family would find themselves in Braintree, where, in 1865, Eli was born, followed by a sister, Minnie, in 1868. Minnie would marry James Dutton Whittles and raise four children, two of whom would later settle in Weymouth.

The 1870 census lists the Bences back in Fall River—father aged 43, machinist, living in Ward 2 in the south end, in a house valued at $2,000 and a personal wealth of $375. Sarah is keeping house, and Eli’s half-brother, Peter Gaskell Bence, is 20 and working in a cotton mill, as is 15-year-old John William. Sarah Jane is at school, and Eli and Minnie are at home.

In the 1880 census the family is living on Bay Street. According to the City Directory, Sarah Jane has become a teacher at Slade Primary and Eli, now 15, is working at 33 Rodman in the city as a clerk. Eli’s father, William, and brother, John William, are listed as working as machinists. Peter Gaskell Bence had married Sarah Jane Bull at the First Methodist Episcopal Church in Fall River, on January 21, 1871. Peter became a patrolman for the Fall River Police Department from 1878-1882, and had lived at 117 Bay Street with his family. By 1880, he was at 20 Grant, and by 1882, he lived just around the corner from his parents’ home on Bay Street, at 5 River View.

In 1884, brother John William is listed as a weaver and living with the couple, and Eli, now 19, is at 8 Granite Block as a clerk, and also living at 117 Bay Street. Peter would sire seven children altogether with two wives. Sarah Jane Bull Bence would die in childbirth in 1890.

In August 1892, Peter Bence married Emma Macomber. From 1880 to 1900, Peter was a policeman, a carpenter, then a school janitor, living at 20 Grant, 117 Bay, and 56 Palmer Street. When Emma died in 1909, Peter moved to Newport to live with his daughter Minnie Bence Kelly and her family, where he died in 1919.

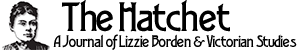

On July 26, 1886, Eli Bence married an English bride, Sarah A. Hayhurst. Their first child was christened Roy Sydney Bence, born February 5, 1889. Eli was just 21 years old on his wedding day, his bride barely 20.The couple lived at 21 Whipple Street. It would be Sarah by his side throughout the Borden ordeal. Whether his wife and family supported his decision to come forward is unknown, but one can speculate about the conversations that must have transpired beneath the Bence roof. Half-brother, Peter Bence, once a police officer himself for the Fall River police department, must have offered advice, and Sunday dinners around the table with the family must have included anxious and pressing questioning about Lizzie’s visit to Smith’s, the inquest and preliminary trial, and ultimately the dismissal of Eli as a witness for the prosecution in 1893.

By 1894, one year after Lizzie’s acquittal, Eli and Sarah had moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where Eli set up a neighborhood apothecary at the corner of 4th and Russell Streets. Roy was now 5 years old when the couple settled down to married life away from the aftermath of Lizzie Borden and Fall River It is hard to know if this move away from family and Fall River had anything to do with the trial, Eli’s part in the case, or the consequences of his moment in the spotlight.

119 Fourth Street (now Purchase Street) is a large, rambling Victorian house in what was an upper middle class neighborhood of similar homes. The apothecary was on the first floor and a walk up steep stairs from the street. The little family lived at 74 Willis Street, in a lovely neighborhood further north in the city. The house is still standing. In 1898 the family moved to 103 School Street, just a short walk to the apothecary store for Eli. That house is no longer standing, but was located in another charming residential neighborhood. But happiness was once again . . . elusive. Sarah died just two weeks before Christmas in 1899, leaving a grieving Eli and an inconsolable 10-year-old son.

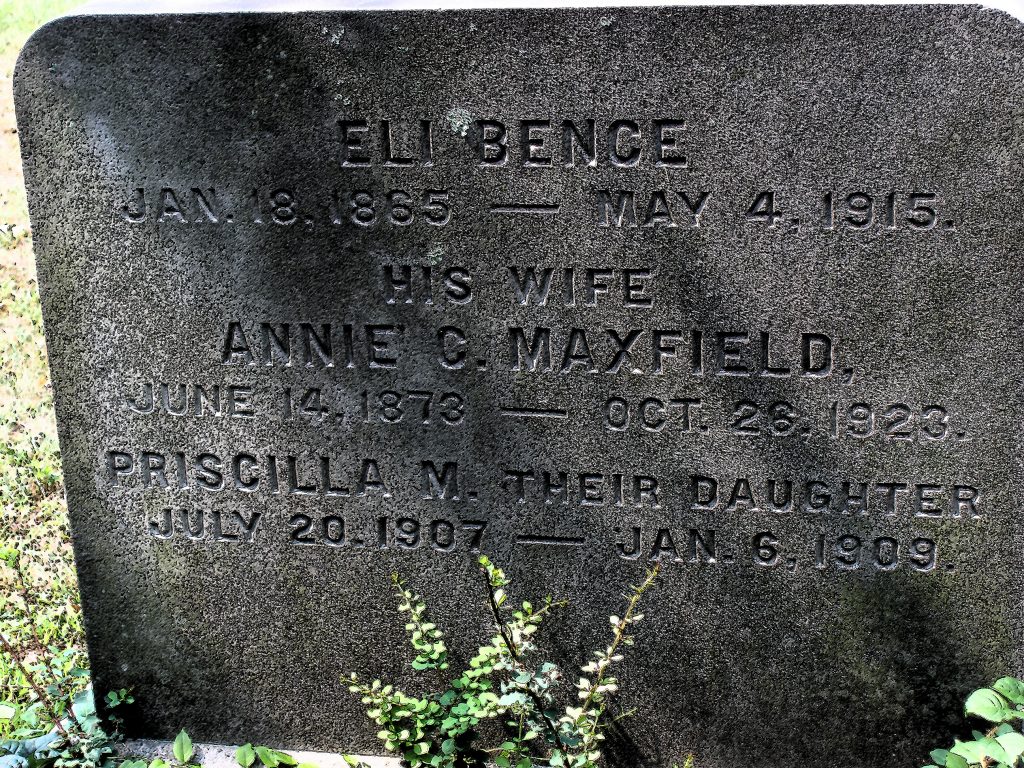

Joy again entered Eli’s life in 1904, when he married Annie C. Maxfield, a school teacher at New Bedford High School. Two years earlier she had been a principal at a small country school in Acushnet. Annie’s father had a thriving plumbing business, C.P. Maxfield’s, on Bridge Street in Fairhaven. Annie had a sister, Nellie, also a schoolteacher, and a brother Frank, a tinsmith apprentice. Annie was just 30 and Eli 38, upon their marriage, with a 14-year-old son for Annie to raise. By 1903, the family appears in the Pittsfield, Massachusetts directory as living at 20 Hamlin Street, with Eli employed at 75 North Street. Later in 1903, Eli set himself up in his own business, an apothecary at 49 North and the Morton Block. The family moves to 23 Howard Street in 1908 with Roy and their new baby girl, Priscilla, born in 1907. Roy—like his father and uncles, went to work as a teenager—helping in his father’s store.

Tragedy would strike yet again with the death of Eli’s precious daughter Priscilla in 1909. In 1910, at the age of 37, Annie presented Eli with Maxfield Hudson Bence, named for her father and Eli’s mother. With business prospering, Eli moved his family to 64 Commonwealth Avenue in 1913, and life was good. Eli had risen to the top of his profession and was held in the highest esteem by his colleagues as a pharmacist, revered by his community and active in the Masons and many civic organizations.

While driving with Annie one May morning in 1915, Eli suddenly became ill, and after a brief illness, succumbed to a cerebral hemorrhage. He died at home at the age of 50, leaving Annie and Maxfield, aged 5, and Roy, now 26 and newly married (July 3, 1914 to Minetta Welton Steel), to mourn. The front page of the New Bedford Standard-Times printed Eli Bence’s obituary on the day after his death, and, as always, the Lizzie Borden trial and Eli’s part in it was retold. Annie lived on until 1923 in Pittsfield, when she joined her husband, and daughter Priscilla, in Riverside Cemetery in Fairhaven, dying also at the age of 50. Maxfield was left an orphan of 13.

Maxfield Hudson Bence went on to become a Lt. Colonel in the U.S. Air Force, serving in WWII and Korea. He married his sweetheart Evelyn, and the two are buried together in Sam Huston Veteran’s Cemetery in San Antonio, Texas. Max died on June 25, 1981.

There is no update on what happened to Roy Sydney Bence, but Bences still are thriving in Pittsfield, Swansea, Weymouth, Rehoboth, and Texas. This may not be the end of the Eli Bence story. As long as the world holds a fascination with Lizzie Borden, Eli Bence will be immortal— and forever the man who might have made all the difference if his voice had been heard by twelve men brave and true in the city of New Bedford in the summer of 1893.