by Mary Elizabeth Naugle

First published in August/September, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Professor Wood, whose part in the Borden case was limited to assuring the court that cause of death was all in the Borden heads and not in their stomachs, began his career much more dramatically as central medical witness in the most notorious poisoning case in New Hampshire history. The case was that of Elwin Major of Wilton Centre, tried and ultimately hanged for the strychnine poisoning of his wife, Ida, who died on December 20, 1874.

Professor Wood, whose part in the Borden case was limited to assuring the court that cause of death was all in the Borden heads and not in their stomachs, began his career much more dramatically as central medical witness in the most notorious poisoning case in New Hampshire history. The case was that of Elwin Major of Wilton Centre, tried and ultimately hanged for the strychnine poisoning of his wife, Ida, who died on December 20, 1874.

While young Professor Wood was opening the stomach from her exhumed body a few days later, a whole can of worms was being opened in the hamlet of Wilton Centre. The central worm was Elwin Major, a cross between Bluebeard and Ernest T. Bass. Major was already suspected of a variety of crimes representing a downwards course from murder to arson, breaking windows in the Baptist church, stealing from the collection plate, and defacing a Bible. Six years before, Major had impregnated a minor, whom he hastened to marry. That minor had been the late Ida Major. Although law did not forbid his marriage to the thirteen-year-old Ida, it did preclude his making an honest woman of her likewise pregnant nineteen-year-old sister, Ella. Ella was mysteriously ushered from this world shortly thereafter—a departure that Ida probably came to envy.

For Ida spent most of her remaining years in confinement, producing four children before her death at age eighteen, one month (Amherst Cabinet, 30 Dec. 1874). A fifth 9 to 10 pound baby was taken from her womb at autopsy (Nashua Daily Gazette, 28 Dec. 1875). Confinement did not mean idleness for Ida, however; Elwin was not one to indulge a slackening of duties. She continued to care unaided for their two living children (two having suspiciously left this realm already) and to split wood, do washing, and carry water from the well. She continued these activities up until a week before her death, when her friend Laura Stiles observed her carrying water from a neighbor’s well, the Majors’ own well having gone dry. Miss Stiles remarked, “If I had a man he should bring the water.” Ida’s dry response was that “she never could find her man to get him to bring water” (Nashua Daily Gazette, 29 Dec. 1875).

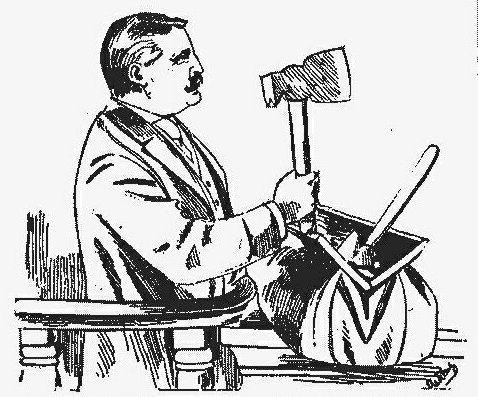

It is no wonder she could not find him. Elwin was busy spreading the rumor that Ida had taken up the dangerous habit of eating camphor, a habit he was sure would bring about her swift demise. He was also busy calling on and chopping wood for young Sarah Howard, whose father had died the month before, leaving her considerable property. Sarah, like most girls who crossed Major’s path, was in an interesting condition, for which Elwin appears to have been seeking remedy. Although Elwin solemnly told Helen Blanchard that “the best physicians in Nashua told him that all the medicine ever manufactured wouldn’t save” Ida, the Nashua doctors later testified that he had actually consulted them in order to procure an abortion for a young lady whose lover was in no position to marry. That service was one all the doctors declined to provide (Nashua Daily Gazette, 29 Dec. 1875).

Most damning of all was the report of Sarah Howard, who by the time of the second trial (the first trial having reached an impasse over the new-fangled tests for strychnine) had given birth to her child and, not surprisingly, named some other obliging young man as the father. She remained unmarried. The court was prepared to despise her as a loose woman and possible accomplice. Her manner must have been remarkable, however, for her testimony won over the assemblage, including an enthusiastic press:

the candid, clear, emphatic and sharp manner in which she gave her evidence, made a favorable impression on all. . . . She was the most wonderful witness of her sex, that perhaps ever took the stand in this State, or any other. As a lady remarked, ‘The manner in which she gave her evidence was a credit to the sex’ (Nashua Daily Gazette, 30 Dec. 1875, 2).

According to Sarah Howard, Major had asked her to stay and look after the children the night after Ida’s death. She obliged, remaining until called home by a mother who was alarmed by rumors already in circulation. Sarah carried the news back to Major. When Howard first told him she had been sent for because of some trouble, he asked if Mother Howard was worried over the bank robbers currently at large. Sarah bluntly told him,“no, the trouble is about you; they have taken up the body of your wife; he said, ‘My God is it so? What shall I do? Have they taken up and cut up my darling wife?’ and said what if they should find strychnia in her? What if she had taken strychnia by mistake?” (Nashua Daily Gazette, 30 Dec. 1875, 1).

This is a curious statement from a man convinced his wife had died in the throes of camphor poisoning. She might have gotten to some strychnia he had lying about—no use looking for it, though, for the bottle was unmarked and he would not recognize it if he saw it. (How very careless of him.) By this time, the cracks in Elwin were beginning to show. He suddenly bethought himself of an old flame, the Kidder girl, who “married an old man and did not live happy,” and whom he intimated was now dead (Nashua Daily Gazette, 30 Dec. 1875, 1). Probably what most impressed the jury was the fact that rather than run screaming from the house, Sarah remained to grill the man with the steely nerve of Bluebeard’s wife:

I told him the body was in the Town Hall and that Drs. Dearborn, Jones and McQuesten had made an examination of the body and took the stomach to Boston to analyze it; . . . I asked him what he would do if they took up Ella’s body and he said ‘my God, they haven’t taken up her body have they?’ I then said what if they should take up the bodies of his two children, and he said, ‘my God, they haven’t done that have?’ [sic] then I said what if they should take up the remains of the Kidder girl, and he replied ‘my God, have they done that?’ he then looked in the almanac to see when he would be tried if arrested; he said when I first told him of the post mortem examination, ‘my God, if they find strychnia in the stomach; there was some in the house and if she took any by mistake what shall I do?’ Monday I found that his story of her eating camphor was not true as I found the bottle with the camphor in it in the closet; Major said he was mistaken and she had not eaten as much as he thought she had (Nashua Daily Gazette, 30 Dec. 1875, 2).

Such were the surrounding circumstances in the case. So far, what the town had were strong suspicions, not hard evidence. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind that the man was a cad and a liar; there was no doubt that he behaved like a guilty man. But unless strychnine could be found in Ida’s system, the law could not touch him.

Enter Dr. Wood.

The local doctors had noted a curious stiffness in Ida’s body, particularly in the extremities. That stiffness coupled with the violent convulsions seizing the girl before death was cause enough to seek an expert opinion. Dr. Wood was that expert. A first trial ended in a hung jury, because jurists were suspicious of the new science that enabled doctors to isolate strychnine from other chemicals in the organs. Their wariness was comparable to early distrust of DNA evidence. In the second trial, conducted a year after Ida’s death, Wood returned more self-assured than ever, and with a battery of medical supporters. His reception was warm:

The witness attracted the close attention of both jury and audience. . . and made a favorable impression by the thorough knowledge he showed of his profession and the cool and collected tenor of his evidence. The cross examination was very searching but failed to disconnect the witness [in] the least. The Doctor was on the stand two hours and thirty-five minutes and as he left the stand the impression of those who followed his testimony was that he ranks as one of the ablest medical experts that ever took the witness stand in our state (Nashua Daily Gazette, 29 Dec. 1875, 2).

Wood’s job would be three-fold. He must first dismiss the suggestion that death was a result of a camphor munching habit. Next, he must dismiss the possible natural cause of puerperal convulsions. Finally, he must prove strychnine poisoning. Professor Wood was not yet thirty, not yet a full professor of chemistry at Harvard Medical College; still, he was well versed in the new processes and had gathered considerable experience in his work at the college and as chemist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

The first hurdle was simple enough. When Wood opened Ida’s stomach, he detected no odor of camphor. The tell-tale odor of camphor is unmistakable. As for the possibility of death by puerperal convulsions, the anecdotal evidence argued against it. Ida was conscious to the end. While Wood granted that puerperal convulsions might resemble the throes of strychnine poisoning, there was one important difference: a strychnine patient “is sensible until the last few spasms or convulsions, while in puerperal convulsions the patient is unconscious.” The third, and most difficult proof was obtained by means of a test called Dragendorff’s Process, which separates the alkaloid poison through analysis of liver samples treated by various acids and chemicals. The “brilliant play of colors” produced by a final introduction of bi-chromate of potash was clear evidence of strychnia, which Wood insisted could not be introduced into the body after death (Nashua Daily Gazette, 28 Dec. 1875, 2). Taking no chances this time, the prosecution brought forward six additional doctors to second Wood’s findings. Two among them, Hayes and Wormley, seasoned experts in the field of toxicology, were being called to give credence to the Dragendorff Process.

The strength of their case was borne out by the desperate summation by the defence, and the best they could come up with was a reminder that the case was circumstantial. The worst was a character assassination of Professor Wood:

Dr. Wood is a young man, he has devoted himself to this particular profession; by it he hopes to acquire fortune and fame. He believes if this case is proven his name will be flaunted through the papers and magazines of this country and Europe. His ambition is strong. I know what the ambition of a young man is; I was young once and had ambition. Ah! I see the folly of it now; but he is ambitious, and I would ask you if this citizen’s life, given by God alone, . . . is to be sacrificed to satisfy the ambition of this young man, I admit in the popular acceptation [sic] of the term a smart man for his years, but his evidence should not be sufficient to take this man’s life.

Dr. Hayes says he found strychnia in what Dr. Woods [sic] gave him, but, gentlemen, how did he or how do you know how Dr. Woods [sic] may have manipulated that stomach or contents before he received them from him (Nashua Daily Gazette, 1 Jan. 1876).

As if the insinuation of evidence tampering were not enough, the defence stooped to an all time low by reminding the jury that “a former professor who occupied the chair Dr. Wood does at Harvard Medical College was hung” (Nashua Daily Gazette, 1 Jan. 1876). This reference to the notorious Dr. Parkman was inexcusable.

When Attorney General Clark addressed the jury, he spent nearly as much time proclaiming Professor Wood’s innocence as he did proclaiming the defendant’s guilt:

. . . I would reply to the very unkind remarks of my brother to Dr. Wood this morning; remarks which I must say were as unkind as they were uncalled for, and I as a friend of Dr. Wood, and I presume he is a friend of mine, feel compelled to say a few words for him in this connection. . . .

He says he is ambitious, yes and my brother has a spark of it in him when he gets warmed up. . . I admit he is ambitious—ambitious for what? for fame my brother says—but my brother well knows that the fame he refers to is not that fame which is sounded round the world in trumpet tones. The man of science seeks and obtains no fame like this, the ambition, which excites and cheers him on in his labors is the laudable desire to benefit by his researches his fellow men. Dr. Wood has already achieved fame in his profession more than generally falls to the lot of so young a man. The desire for fortune as my brother says, is too thin as the saying is, to have any effect with you gentlemen, for the paltry sum he receives for his services here, is scarcely enough to pay him for coming here, and no fortune, the universe itself gentlemen is not fortune enough to bribe Dr. Wood to commit so base a crime as insinuated by my learned brother against him. (Nashua Daily Gazette, 3 Jan. 1876, 2).

Attorney General Clark continued with a discussion of the additional tests run by Dr. Hayes and corroborated by Professor Wormley. He then presented an extremely persuasive argument for the airtight nature of the circumstantial evidence in the case, but his final words were in praise of Professor Wood: “The whole case hinged upon Dr. Wood’s testimony and he stands vindicated as one of the most reliable and trustworthy medical experts in the country” (Nashua Daily Gazette, 3 Jan. 1876, 2).

One year later Elwin Major went to the gallows. The much maligned Professor Wood, on the other hand, was by then a full professor at Harvard.