by Denise Noe

First published in Fall, 2009, Volume 6, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Unleashed on the world!

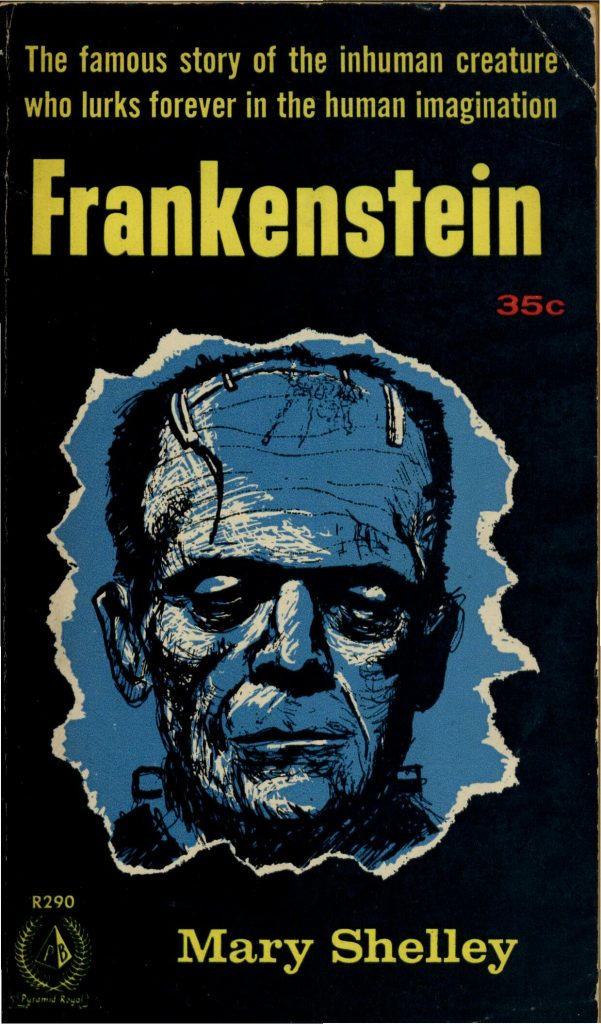

Since Mary Shelley unleashed the extraordinary novel Frankenstein on the world in 1818, the Creature, often called by the book’s title, has securely fastened onto the common imagination. Perhaps no fictional creation more deeply frightens and more utterly enthralls than the being Victor Frankenstein fashioned out of the parts of human corpses and brought to life via the zing of electricity.

Since Mary Shelley unleashed the extraordinary novel Frankenstein on the world in 1818, the Creature, often called by the book’s title, has securely fastened onto the common imagination. Perhaps no fictional creation more deeply frightens and more utterly enthralls than the being Victor Frankenstein fashioned out of the parts of human corpses and brought to life via the zing of electricity.

Frankenstein has inspired a multitude of motion pictures and probably a myriad of nightmares. Every Halloween, little tykes wearing green Frankenstein masks and carrying trick-or-treat bags venture from house to house. Perhaps because he triggers so many primal fears, Frankenstein has been domesticated in other respects as well. He made weekly appearances in American living rooms as Herman Munster, through the television series The Munsters (1964-1966). In that show, the Frankenstein-like Herman was an amiable TV sitcom dad with a hearty laugh and childlike personality. He often got into scrapes from which his more sensible vampire wife Lily had to bail him out.

The horror soap opera, Dark Shadows (1966-1971), once had a character modeled on the personage made famous by Mary Shelley’s classic. Unlike most depictions, Dark Shadows’ hearkened back to the novel in showing the corpse-created creature developing his intellect.

Frankenstein even makes a peculiarly wholesome appearance at the breakfast table as Franken Berry, a General Mills cereal.

Frankenstein is comparable to Dracula, Dorian Gray, and the doubled character of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in that all are figures of horror that have completely permeated the common consciousness of the Western world. (This writer is especially desirous of drawing attention to the illustrious literary personages of Dorian Gray and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, as my essays about them have graced the pages of this journal.)

The novel, and character, of Frankenstein were born in the Regency era, the period preceding the Victorian era in which the savage Ripper and Borden murders took place. Like “Victorian,” “Regency” owes its name to the British monarchy. While the Victorian era derived from the very name of a British ruler, the Regency took its name from a ruler’s official title: when George III was deemed not fit to rule, his son, George IV, became Regent in the period 1810-1820.

We cannot know whether or not Lizzie Borden, or any of the Bordens, read Frankenstein. However, it is quite possible that Lizzie, Emma, Abby, and/or Andrew took a dip into this work, since it has been popular from

the time of its first publication. Lizzie and Emma had quite a bit of time on their hands both before and after the murders, and Lizzie is believed to have been an avid reader.

In our own era, it is probable that more people are familiar with this Regency-era work through the multitude of movies it has inspired, than have read the novel itself. However, it is both useful and fascinating to examine the source of the extraordinary figure of Frankenstein.

The daughter of –

A teenager wrote Frankenstein on a dare. That hardly seems an auspicious beginning for a classic. However, this particular teen had a background tailor-made to nurture her intellect and inspire her imagination.

Born in London, England on 30 August 1797, Mary Godwin (she would become Mary Shelley on her marriage) was the child of two of the most controversial thinkers of the day. Her father, William Godwin, was the author of Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793). Her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, had written A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792).

Mary Wollstonecraft already had one daughter, 3-year-old Fanny Imlay, before Mary. Fanny had been born out of wedlock during an era in which this was considered disgraceful. However, Wollstonecraft held the then-radical view that motherhood could never be anything other than honorable regardless of marital status. Both she and Godwin had reservations about the custom of marriage, but wed during her pregnancy. Eleven days after giving birth to Mary Godwin, Mary Wollstonecraft died.

Godwin and Wollstonecraft had enjoyed a passionate love coupled with intellectual affinity. As a widower, Godwin determined to honor his late wife’s memory by sharing her life story with the world. He started going through her papers the day after her funeral and was soon at work on her biography. That work was published in 1798, as Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman. It was filled with admiration for Mary Wollstonecraft, but did not sugarcoat her life. Godwin wrote about her suicide attempts as well as her intellectual work. Nor did Godwin shy away from the truth that his late wife had enjoyed a romantic life prior to him; he wrote frankly of her crushes and affairs.

At the same time as Godwin labored to immortalize his late wife, he cared for his infant daughter and stepdaughter. According to a biographical essay by Eleanor Ty, Godwin could not help but play favorites between daughter and stepdaughter. Ty states, “He called her ‘pretty little Mary’ and relished evidence of her superiority over Fanny.” Godwin supervised the childhood education of both youngsters and, according to Ty, “took them on various excursions—to Pope’s Grotto at Twickenham, to theatrical pantomimes, and to dinners with his friends James Marshall and Charles and Mary Lamb.”

In 1801, Godwin met a woman who called herself “Mary Jane Clairmont.” She told him that she was a widow. She had two children, 6-year-old Charles and 3-year-old Jane (Clair). In reality, her last name was “Vial” and she had never been married.

She attained the wedded state with William Godwin. The relationship between Mary Jane Godwin and young Mary Godwin was strained. The adult woman was jealous of the bond the child had with her father and bristled at the interest so many people showed in the child of two famous authors.

The second Mrs. Godwin was not without business acumen, nor was she a philistine lacking appreciation for literature. She was instrumental in founding the Juvenile Library of M.J. Godwin and Company that provided the financially struggling family with much needed, albeit haphazard, income.

In 1812, Mary Godwin met two close friends of her father: Percy Bysshe Shelley and his wife, Harriet Westbrook Shelley. Born to wealth, Percy Shelley had published two novels before he was out of his teens. Ty reports, “Percy Shelley shared Godwin’s belief that the greatest justice is done when he who possesses money gives it to whomever has greatest need of it. Therefore it was not long before Shelley was supporting Godwin financially.”

In addition to being rich, intelligent, and accomplished, Percy Shelley was tall, slender, and elegant. Mary Godwin was immediately attracted to the married man and he to her. A romance soon blossomed. When William Godwin discovered that his daughter was entranced by another woman’s husband, he insisted that Percy Shelley cease visiting the Godwin home—although Godwin continued accepting money from him.

Mary stopped seeing Percy. According to the Percy Bysshe Shelley chapter of the website Neurotic Poets, Shelley “showed up distraught and hysterical at her house with laudanum and a pistol, threatening to commit suicide.” Mary began seeing Shelley again, despite her father’s disapproval. In July 1814, the couple, accompanied by Mary’s stepsister Jane Clairmont, eloped to France.

There they lived in precarious economic circumstances. Although Percy was from a wealthy family, funds were tied up because of disputes about his grandfather’s estate. Thus, the couple scraped by financially as they moved from one residence to another. Mary became pregnant and gave birth four times, but only one of her offspring lived to adulthood. Their first child was born in 1815, and died eleven days later. William was born in 1816, and died of malaria in 1819. Clara Everina was born in 1817, and died of dysentery in 1818. Percy Florence was born in 1819, and lived to grow up. Mary Godwin got pregnant in 1822, and miscarried.

The aforementioned tragedies were not the only ones that beset Mary during these years. In 1816, both Fanny Godwin and Harriet Shelley committed suicide. It is likely that Mary mourned her half-sister’s death. She may also have felt guilt at learning that the woman whose husband Mary had eloped with had killed herself.

However, the resilient Mary wrote History of a Six Weeks’ Tour through a Part of France, Switzerland, Germany, and Holland, with Letters Descriptive of a Sail round the

Lake of Geneva, and of the Glaciers of Chamouni, a book that was published in 1817.

Jane Clairmont continued living with Mary and Percy. Jane also enjoyed a romance with the famous—some would say infamous—Lord Byron. She wanted Percy and Mary to go with her to meet up with the rakish poet. The trio set off in May 1816, and moved into a chalet close to Lake Geneva, close to Villa Diodati where Byron was staying with his physician, Dr. John William Polidari.

One evening, in June 1816, it was raining and the group gathered around the fireside. Gloomy weather and confinement indoors are often conducive to a deliciously morbid mood. The group began amusing itself by reading aloud from a book of ghost stories.

Then, Lord Byron burst out with a diverting suggestion. He proposed that each of the assembled group write a horror story. Byron read the start of his the next day. Percy Shelley began one, as did Polidari.

Mary pondered the project, but found herself unable to come up with an idea. When the others queried, “Have you thought of a story?” Mary repeatedly replied “No.”

One night she, Byron, Polidari, and Percy Shelley discussed the subject of “galvanism,” and a story making the rounds that naturalist and botanist Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles Darwin, had somehow caused a piece of pasta to move on its own. This triggered a fantasy in Mary in which she imagined a man “kneeling beside the thing he had put together,” and brought to life. She was terrified by the fantasy—and had the spark that would flame into the unquenchable fire of Frankenstein.

The fire imagery in the above description was deliberately chosen as the novel’s full title is Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus. Prometheus is a figure from ancient Greek mythology who took fire from the gods to give to humans and was punished for the usurpation by Zeus. It is a measure of the genius of Mary Shelley that “Frankenstein” is now so much more thoroughly enshrined in the popular mind than the Prometheus he was said to have tragically emulated.

Devil, demon, fiend – cruelly wronged

The stories within the novel Frankenstein encase each other like a series of Chinese nesting boxes. The novel is bracketed by the tale of Robert Walton that is told through his letters home to his sister. A valiant explorer, Walton was determined to lead his crew to the North Pole. When sheets of ice trapped Walton’s ship, a sledge on a large piece of ice drifted toward the boat. On it was the emaciated and ill Victor Frankenstein. While Walton cared for Frankenstein, the latter told him the story of his life. Within that story, Frankenstein recalled for Walton the story of his creation’s life as the creature told it to him. Within the creature’s story is yet another tale, that of a group of cottagers. Spark Notes on Frankenstein reports, “Many critics have described the novel itself as monstrous, a stitched-together combination of different voices, texts, and tenses.” This complex narrative structure seems appropriate to a work so rich in plots and themes.

The story of Victor Frankenstein is one of high hopes and extraordinary overreaching. Frankenstein related that he grew up in Geneva, Switzerland reading the works of the alchemists. As a youth, he attended a university where he became fascinated by the basis of life and determined to uncover its secrets. He believed he could create a new species that is not human, but from the human species. Frankenstein raided cemeteries, taking bodies to use in his experiments. From various corpses, he surgically patched together a body that was eight feet tall. Then he used the methods he had uncovered to bring his creation to life.

The story of Victor Frankenstein is one of high hopes and extraordinary overreaching. Frankenstein related that he grew up in Geneva, Switzerland reading the works of the alchemists. As a youth, he attended a university where he became fascinated by the basis of life and determined to uncover its secrets. He believed he could create a new species that is not human, but from the human species. Frankenstein raided cemeteries, taking bodies to use in his experiments. From various corpses, he surgically patched together a body that was eight feet tall. Then he used the methods he had uncovered to bring his creation to life.

Frankenstein found himself appalled by the appearance of his creation when it came to life: “His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful! Great God! His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun-white sockets in which they were set, his shriveled complexion and straight black lips.” Viewing the creature as ugly, the scientist fled from it. Soon, the new being found his creator: “His jaws opened, and he muttered some inarticulate sounds, while a grin wrinkled his cheeks.” Frankenstein recalled that, “one hand was stretched out, seemingly to detain me, but I escaped . . . ” The phrasing of the last sentence indicates that Frankenstein saw the creature as attempting to aggressively “detain” him, while the grin and outstretched hand seem to the reader to indicate that the creature was attempting to make friends with his creator.

Based solely on repugnance for the new being’s appearance, Victor Frankenstein rejected his creation. While Frankenstein was outside his living quarters, the being wandered away from it.

Frankenstein lost track of the creature he brought to life. After a period of separation, the length of which is never made clear, Frankenstein learned of tragedies that he was certain the “monster” must have caused. Victor’s much younger brother, a child named William, had been found strangled to death. Justine, a young woman who was employed in the Frankenstein household as a servant but loved as a family member, was suspected of the murder because an item known to be worn by William was found on her person. Although she was innocent, Justine was convicted of the murder and executed for it.

Meeting up with his maker

Eventually, the creature found Frankenstein. The being had learned to talk, and had become literate in their time apart. He reproached Frankenstein for the injustice of his rejection, saying, “Remember that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed.”

Then the creature related to his maker the story of the process of his learning—and the mental and physical agonies he suffered. Like the original Adam, Frankenstein’s creature had come to life as physically adult. However, he had the unformed mind of an infant and that may set him apart from Adam. In sharpest contrast to Adam, this being had to make his way in the world with no assistance from his maker.

After first parting from Frankenstein, the creature stumbled through the forest, and found berries to eat. Seeking shelter, he wandered into a hut. Its resident shrieked and ran from the intruder. Later, the creature walked into a small village where the terrified people immediately attacked him with stones and other weapons. Bruised and battered, he escaped.

Taking refuge in a hovel adjoined to a cottage, the creature discovered a chink in a wall through which he could observe his neighbors. The cottagers aroused emotions of fascination and caring in the being, who learned to speak by listening to them. The cottagers were a young woman named Agatha, a young man named Felix, and an elderly blind man called only “Father.”

Bubbling over with affection for his neighbors, the creature began secretly doing chores for them. Making use of the cottagers’ tools, he chopped wood and delivered a big pile of it to their doorstep. He made a regular practice of such deliveries and performed other tasks on their behalf, such as clearing their path of snow. He also heard the astonished cottagers ascribe these gifts of goods and services to a “good spirit.”

The story of the cottagers thickened when the three were joined by a woman named Safie, who was not part of the family, but was connected to them through a dramatic past. Through his chink in the wall, the creature learned that the family suffered a steep fall in their economic and social circumstances. The knowledge of their sad past endeared them even more strongly to the creature.

Yearning for a positive connection, the creature determined to introduce himself to the cottagers. While

Felix, Agatha, and Safie were out, the creature visited the blind father. Unable to see, the father was instantly sympathetic to his lonely, troubled visitor. However, the three with vision returned and were aghast at the sight of the creature. Felix physically attacked the creature who fled this latest and most lacerating rejection.

The creature then decided that he must re-unite with his creator. On his way, he came across young William, and learned of his relationship to the maker whom the creature held responsible for his misery. In a fit of rage, he murdered the young boy. Then he encountered the sleeping Justine. The lovely young woman reminded the creature of how his own ugliness barred him from even receiving a smile from a woman like her, so he framed Justine for William’s killing.

When the creature found Frankenstein, the creature admitted to his crimes but pointed out that he was enraged because of his misery, a misery for which Frankenstein bore responsibility, since he made the being and then rejected him. He demanded that Frankenstein create a partner for him, his own Eve, crafted from corpses and animated through the same means that brought him to life. This demand leads to the novel’s haunting denouement.

One of the most significant aspects of Frankenstein is that Victor Frankenstein never names the being that he has crafted and brought to life. He calls him the “creature,” “demon,” “devil,” “fiend,” and “monster.” His failure to give him a name appears indicative of his rejection of him.

Literary purists may point out that it is not true to the story’s origins to call the creation, rather than the creator, “Frankenstein,” as is so often done. However, this conflation can be defended as something more than confusion since there is a tradition of naming inventions after their inventors. What’s more, the creature is, in a sense, Victor Frankenstein’s child.

One of the major themes of Frankenstein is the inevitably intimate tie between the creation of life, and death. This was something that had to weigh heavily on Mary Shelley, as her own birth had led to her mother’s death. Like most fertile and heterosexually active women, Mary Shelley had repeatedly risked her own life in childbirth—only to watch her children die before they had a chance to grow up.

Her novel switches reality around because it has a man bringing life, unaided by a woman’s danger-filled sacrifice of childbirth. Significantly, the man is mortally threatened by the life he has brought into being. This parallels the dangers of childbirth.

James Whale creates the cinematic paradigm

As previously noted, Frankenstein has monumentally inspired the motion picture industry. Director James Whale set the paradigm for cinematic depictions of this story with his 1931 Frankenstein. The story, as it appears onscreen, does not hew closely to that of Mary Shelley. Instead, it draws upon Shelley’s tale, but shows the audience the special vision of James Whale. The director sheared off the story of Robert Walton, and jettisoned that of the cottagers.

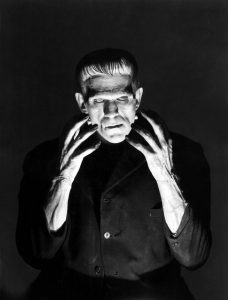

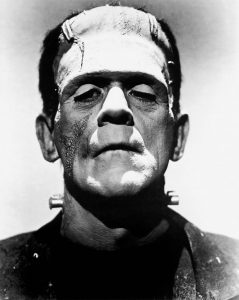

Played by Colin Clive, the scientist is still Frankenstein, but has the first name “Henry.” Boris Karloff stars as “The Monster,” although the film credits pointedly list only a “?” for the role. When people think of “Frankenstein,” it is likely that the image that springs to mind is that of the Whale-Karloff, square-headed and deep-eyed, creation as seen in the original Frankenstein, or one of its multitude of imitators. Joyce Carol Oates succinctly captures this Frankenstein as a “retarded giant” sporting “electrodes in his neck.”

Colin Clive brings an over-the-top enthusiasm to his role of the scientist obsessed with inventing new life. The scene in which he exuberantly cries, “It’s alive! It’s alive!” is justifiably one of the most famous in cinema.

While Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein robbed graves and stitched corpse parts together in solitude, a hunchbacked dwarf named Fritz aids Whale’s Henry. The movie is not set, as the novel was, in the 19th Century, Shelley’s contemporary period, but in the 1930s, the period contemporary to the making of the film.

Decades after being released, Frankenstein retains the ability to draw audience interest and hold it through each scene. Whale deserves much of the credit for the film’s classic status, as he obviously put painstaking care into crafting it. The film is energetically paced and beautifully atmospheric. It may not quite have the ability to scare that it possessed when its special effects were fresh, but it has lost none of its excitement. Perhaps one of the factors ensuring its classic status is the expert manner in which Whale skips from the eerie atmosphere of a foggy night to the sunlit innocence of an alpine morning, and a young girl offering the Monster a flower.

The Monster in the 1931 film never approaches the cultured refinement of the novel’s creation, but he retains something of the spirit of the original in combining dangerousness with innocence. Karloff’s Monster is a threat to society, but he is also a victim. Possessing the mind of an infant and a physically powerful body, his destructiveness is not his fault, but

that of the humans who fail to nurture him and set out to destroy him as soon as the experiment is regretted. He kills humans, but the killings are either in self-defense or committed inadvertently because of his childlike ignorance. When the Monster innocently kills, Whale draws a (perhaps inadvertent) parallel to the many people who, like Mary Shelley, have innocently killed their mothers by coming into being. The scenes in which the Monster plays with flowers underline the truth of his basic innocence, and those scenes in which the mass of villagers, torches in hand, hunt him down, inevitably provoke pity for him.

James Whale’s sequel, The Bride of Frankenstein, was released in 1935. In this version, the part of “The Monster” is credited to “Karloff,” and it is the part of “The Bride” that is credited with a tantalizing “?” The film begins with Mary Shelley (Elsa Lanchaster), Lord Byron (Gavin Gordon), and Percy Shelley (Douglas Walton) all garbed in 19th Century attire and sitting in a spacious living room. Mary informs both her husband and close friend that there is more to the story of Frankenstein and his creation than she had previously revealed.

The film segues into a series of flashbacks from the first Frankenstein—and a gaping plot hole. The 1931 movie is set contemporaneously to the movie’s making. The 1935 Bride of Frankenstein tells us that this was a story spun by Mary in the 19th Century!

The hole is never plugged—characters in this film, within Mary’s tale, appear in 1930s fashions—but Bride of Frankenstein is an exciting, beautifully crafted motion picture. It is also one of those rare sequels that vies with its predecessor as to which is best.

We learn that the Monster survived the fire that was believed to have killed him. A pivotal new character is soon introduced in Bride of Frankenstein. He is Dr. Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger), an oily scientist with the same obsession about artificially creating life that Henry Frankenstein once had. Dr. Pretorius finds Frankenstein and insists that the two of them must collaborate. Pretorius enthusiastically toasts, “To a new world of gods and monsters.” (Gods and Monsters became the title of the 1998 movie speculating on what the end of director James Whale’s life might have been like.)

Dr. Pretorius has been conducting his own experiments in the creation of new life. In one of the most memorable scenes of a movie (the cup of which runneth over with remarkable scenes), Pretorius unveils a series of small, living humanoid creatures that he has supposedly cultivated. He wants to super-size the work and needs Henry Frankenstein’s expertise for that.

Henry Frankenstein demurs, as he does not want to take a chance on causing more destruction, but Dr. Pretorius finds a way to force his agreement and the pair attempt to bring a mate for the Monster to life.

The Monster depicted in this motion picture has even more in common with the sad creature portrayed in Shelley’s novel than he does in Whale’s previous film. He does not become literate, but it is evident that he is teachable. Inspired by the novel’s cottagers, Whale brings in a single blind cottager (O.P. Heggie), into whose home the Monster stumbles. Unseen by the blind man, the Monster is un-feared. Learning of his visitor’s lack of speech, the cottager notes, “You too are afflicted.” Later, the cottager speaks of how he has “prayed to God for a friend” and now his prayers have been answered. Smiling and relaxed, the childlike Monster is endearing when he says, “Friend. Good.”

The scenes in the cottage possess a startling poignancy. In his physical blindness, the cottager is able to see the possibility for goodness that lies in the Monster. However, the Monster is soon on the run again as those who possess vision see him as only “the Monster.” He finds a protector and guide—as well as a manipulator and exploiter—in Dr. Pretorius.

Bride of Frankenstein ends on a powerful note. Although credited with a question mark, Elsa Manchester plays the Bride as well as Mary Shelley. Dr. Pretorius announces, “The bride of Frankenstein!”

Unlike the Monster, who has been created ugly by ordinary human standards, the Bride is a creature of beauty, albeit deliberately odd beauty. Stitches evident on her face, her hair dark with white streaks and styled in massive waves jutting about her head to suggest shocks of electricity, she looks about herself with mechanical starts and stops. Her eager groom approaches her—only to find that she screams in horror. The Monster is crushed to find that “she hates me like all the rest of them.” A single tear trickles down his face, creating an indelible image of rejection.

Horror into comedy

As noted, many movies have been made about Frankenstein. The majority have been horror films, but quite a few have been comedies. Bud Abbot Lou Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) was an early movie that made the most of the humorous possibilities inherent in the story.

In 1974, Young Frankenstein was released. This comedy/horror/sci-fi combo was directed by Mel Brooks and featured the sort of rowdy antics an audience is apt to expect from a Mel Brooks movie. Gene Wilder played Dr. Frankenstein, Peter Boyle the Monster, and Cloris Leachman the housekeeper, Frau Blücher. Young Frankenstein was filmed in black and white to recall the James Whale movies to which it gives its own peculiarly humorous spin.

Perhaps the most famous Frankenstein-inspired comedy is the cult film The Rocky Horror Picture Show. As critic Roger Ebert wrote, “The Rocky Horror Picture Show is not so much a movie as more of a long-running social phenomenon. When the film was first released in 1975 it was ignored by pretty much everyone, including the future fanatics who would eventually count the hundreds of times they’d seen it. Rocky Horror opened, closed, and would have been forgotten had it not been for the inspiration of a low-level 20th Century-Fox executive who talked his superiors into testing it as a midnight cult movie. The rest is history. At its peak in the early 1980s, Rocky Horror was playing on weekend midnights all over the world, and loyal fans were lined up for hours in advance out in front of the theater, dressed in the costumes of the major characters.”

A musical comedy, The Rocky Horror Picture Show is deliberately and flamboyantly silly. Brad Majors (Barry Bostwick) and Janet Weiss (Susan Sarandon) are an engaged couple who appear quintessentially wholesome. The car they are in gets a flat tire. Although in America, they go to a castle (!) to find a phone. Instead, they find transvestite scientist Dr. Frank-N-Furter from the planet Transexual, of the galaxy Transylvania. Frank-N-Furter is in the process of creating his own being, the Rocky Horror (Peter Hinwood). Mary Shelley inspired the plot, but it functions primarily as a vehicle for a spirited spoofing of the horror and science fiction genres, and has equally spirited fun with many of the permutations of sexuality.

A film Frankenstein that returns to its source

In 1994, director Kenneth Branagh released a movie called Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The title was a pointed assertion that this film hewed closer to the original novel than most cinematic tellings of the tale have—and it did.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein starred Robert De Niro as “The Creature,” and Branagh himself as Victor Frankenstein. This version resurrected Captain Robert Walton (Aidan Quinn) and his voyage to the North Pole, encasing the story of the scientist and his creation. Astute critic Roger Ebert found this “unnecessary” but this writer thinks it adds depth and nuance to the film just as it did to the novel. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was beautifully filmed in largely bright and primary colors. It featured good performances, especially by De Niro. The scenes in which he observes the cottagers and assists them—anonymously providing food instead of the

novel’s gifts of firewood—were genuinely moving. As in the novel, this movie shows a creature who is intelligent and learns quickly, and is all the more pathetic for his ability to comprehend his situation. De Niro credibly depicted the caring, compassion, and the vulnerability of a yawning loneliness, as well as the creature’s rage and hatred, when he is spurned by those he has loved.

The Victor Frankenstein in this movie becomes obsessed with creating life because his own mother died giving birth to his youngest brother, William. This scene prefigures the powerful one in which Victor brings the creature to life, holding onto a naked man with both

Maker and Made awash in water

Overall, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is an interesting and worthwhile film. However, it misses complete success as the pace is often overly frenetic and the scenes overheated. Nevertheless, Branagh shows that he appreciates the issues raised by Shelley’s novel, published in 1818 as a Gothic counterpoint to the literature of the period, and that is commendable.

What would Lizzie have thought?

If Lizzie Borden had read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, would Lizzie have identified with some of its characters? Quite possibly. However, it seems unlikely that she would have identified with Robert Walton. There is no evidence that our Miss Lizzie ever had any thirst for scientific discovery. She would also not have seen herself in that aspect of Victor Frankenstein’s character.

Some students of the Borden murders believe that Lizzie was innocent, but linked to the guilty party. For example, there is a theory that a frustrated suitor of hers committed the murders because Andrew opposed a marriage between himself and Lizzie. Others have speculated that Emma committed the murders out of love for her younger sister (as well as self-interest) because of the fear that Andrew planned to cut his daughters out of his will. If either of these theories, or others, that link Lizzie in a causal respect to the actual murderer are correct, Lizzie may have felt close to the Victor Frankenstein character, who was horrified to realize that he had unleashed a dangerous being on the world.

Lizzie would have identified with at least some parts of the story of the creature, if not before his murders, then certainly after them. The creature begins as benevolent, anonymously helping the cottagers. Prior to her family’s slaying, Lizzie was known for her good works. If she murdered her step-mother and father, she may have been motivated by a sense of rejection and mistreatment similar to that which led Frankenstein’s creation to murder. The creature escapes blame by the public, as well as punishment for the murder of little William, and a guilty Lizzie could have identified with this part of his story as well.

The ostracism that Lizzie suffered after her trial meant that she knew well the creature’s feelings of rejection and loneliness, and this would be true regardless of her involvement in the crimes, or lack thereof.

Perhaps Lizzie saw her life reflected in the sad fate of Justine, accused of a heinous crime that she had not committed. Unlike the tragic Justine, Lizzie was neither convicted nor executed. However, like Justine, she may have been unfairly suspected. The isolation in which she lived after the trial constituted a form of punishment, and one that may have been unjust.

We cannot know for certain whether or not Lizzie Borden read Frankenstein. Nor can we know with certainty what character she might have most identified with if she had read this extraordinary novel. However, we can predict with confidence that both Lizzie Borden and Frankenstein will continue to inspire creative artists throughout time.

Works cited:

Ebert, Roger. “The Rocky Horror Picture Show.” 1 January 1975. RogerEbert.com 1 November 2009. <http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19750101/REVIEWS/ 501010356/1023>.

“Frankenstein: Themes, Motifs & Symbols.” Spark Notes. 1 November 2009 <http://www.sparknotes.com/lit/frankenstein/themes.html>.

Mondragon, Brenda C. “Percy Bysshe Shelley.” Neurotic Poets. 1 November 2009 <http://www.neuroticpoets.com/shelley/>.

Oates, Joyce Carol. (Woman) Writer: Occasions and Opportunities. NY: E. P. Dutton, 1988.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus. London: H. Colburn an R. Bentley, 1831. The Internet Archive. 1 November 2009 <http://www.archive.org/details/ghostseer01schiuoft>.

Tye, Eleanor. “Mary Wollstonecraft (Godwin) Shelley.” British Romantic Novelists, 1789-1832. Ed. Bradford Keyes Mudge. Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 116. Gale.