by Denise Noe

First published in Winter, 2009, Volume 6, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Human beings are fallible creatures. We are not only fallible but can be utterly disrespectful of our fellows and even vicious towards them (as well as toward non-human animals). The Borden murders, regardless of who committed them, are only one example among an endless number of crimes that show how cruelly people can harm other people.

Thus, throughout recorded history—and probably even in prehistoric times—humans have sought to restrain the destructive impulses of those who are unwilling or unable to control themselves. In other words, we have sought to “police” our environment. Police are a vital component of civilization. Since police in the United States wear blue uniforms, it has been said that they are “the thin blue line” that prevents an eruption of chaos in the midst of civilization.

The city of Fall River, Massachusetts, so well known to readers of this journal and dear to some of them, boasts a police department with a distinguished and often colorful history. The recently retired Fall River Chief of Police, John M. Souza, writes on the official website of the Fall River Police Department that it “has the enviable distinction of being one of the oldest police departments in the country. Our long and proud tradition dates back to 1854, when the first constable hit the street to begin his tour of duty.”

Although the present FRPD traces its origins back to that first constable of 1854 when the city charter was adopted, there was law enforcement in the town prior to that. In 1636, the General Court at Plymouth elected constables. The website states, “After the union of colonies in 1692, the General Court of Massachusetts passed a law requiring ‘tithingmen’ to be chosen in every town.” However, the function of these officials appears to have evolved from police duties to the limited and archaic role of enforcing the laws of the Sabbath.

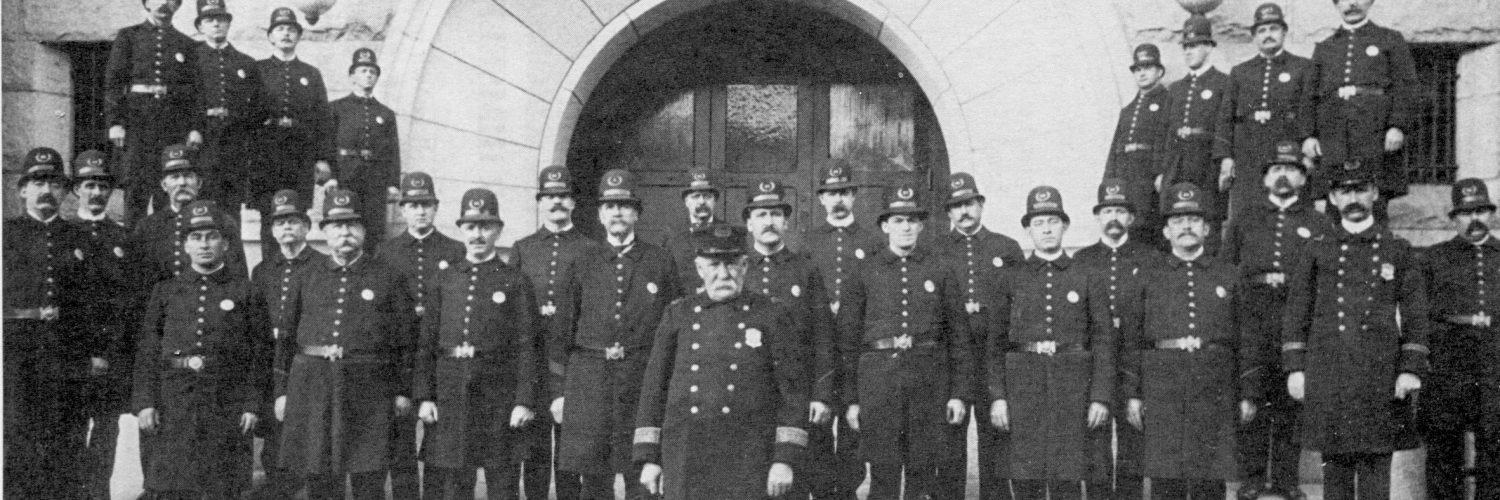

With the creation and acceptance of the Fall River city charter, a total of fifteen men were on the Fall River (police) force—seven of them serving during the daytime and eight during the night. It is easy to surmise that an extra police officer was thought necessary after dark as so many criminals use the cloak of darkness to cover their nefarious activities.

As the population of Fall River increased, criminal activity inevitably grew and, with it, the police department expanded to keep pace. By 1872, the force of the Fall River Police Department consisted of twenty-eight men, “twenty two of whom were on night duty.” By 1874, the total force number had risen to seventy.

In those days, the City Marshal kept a list of arrestees by occupation. According to the FRPD, “In 1877, among those listed were one phrenologist, two physicians, one school master, one music teacher, one druggist, eleven firemen, two undertakers, and one hundred forty four housekeepers. The remainders were laborers, spinners, and weavers. Out of a total of 2,419 arrests, 1,319 were for drunkenness.”

The brief information quoted above is richly evocative of the Fall River of the 19th century. “Phrenologist” is an occupation that might be unknown to many 21st century people—although it will be familiar to most readers of The Hatchet who are likely to be well acquainted with all things Victorian. Phrenology was the belief that mental and emotional characteristics correlated with particular configurations of the skull, and a phrenologist’s vocation was “reading” individual psychologies by analyzing bumps on the head.

It is fascinating to note that, by far, the largest numbers of those arrested were designated as “housekeepers.” Domestic service provided employment to a great many people in the 1800s. Prior to the introduction of such modern conveniences as vacuum cleaners, laundry machines, and dishwashers, cleaning a house and keeping it operating took a great deal of time and work so many people found occupation in this field of service. Anyone familiar with the Borden case knows that, at the time of the murders, the family employed a maid, Bridget Sullivan. Before Bridget, the family had employed a servant whose name is unknown to us. Popular myth states that her name was “Maggie” and that that is the reason why Emma and Lizzie called Bridget by that name, a practice by which Bridget testified she was not offended.

It should also be noted that “housekeeper,” as used in 19th century records, might include people who were not employed in domestic service but who were “Keeping House” for their own families. IPUMS USA makes the point that the term “housekeeper” was often used for people, usually female, who were outside the paid labor force. Women who might be called “housewives,” “homemakers,” or “stay-at-home moms” in more recent or contemporary terms could have been designated as “housekeepers” in the quoted records. “Housekeeper” might also have included unmarried adults, such as grown daughters (like Emma and Lizzie), aunts, and grandmothers who were not servants but who performed domestic chores in the households in which they resided.

However, housekeepers were not among the most highly paid workers, and either the Domestic, or the poor, downtrodden Mistress herself would have endured stresses connected with low incomes or with working on a very intimate basis with demanding or irritable employers (or relatives) that contributed to their committing other offenses. Some students of the Borden case believe that Bridget Sullivan was the true culprit in the crimes and have cited possible strain with Abby and Andrew Borden as reasons to see her as guilty.

“The remainder” of those arrested in the account quoted earlier were employed as “laborers, spinners, and weavers.” Few people in today’s United States work as spinners and weavers because these jobs have, to a large extent, been automated out of existence or outsourced overseas by American companies. Laborers are not uncommon, but much less prevalent than in earlier times, as so many factory positions have become heavily mechanized in our era.

That over half of Fall River arrests in 1877 were for drunkenness also tells a tale. Since this period was well before Prohibition and the consumption of alcohol was legal, it must be surmised that those arrested were drunk in public. Intoxication is often an all-too-tempting way to soothe one’s pains, both physical and psychological, for those who do manual labor and/or suffer the deprivations of poverty.

Pre-Borden Fall River Murders

A murder in 1891 reminds us that America is a nation of immigrants—a fact responsible for the glorious diversity of our national character, but also inevitably the source of tensions that can sometimes turn tragic. Indeed, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Fall River was the leading manufacturing center for cotton cloth and thus was a special magnet for people who journeyed to the United States from other countries, seeking employment in a trade. In Alfred Lima’s book, A River and Its City, the author describes Fall River’s population: “In the mid 1870’s, the Fall River workforce was 25% American natives; 33% English (most from Lancashire); 20% Irish; and about 20% French Canadian. The next great wave of immigration came from the Azores Islands, a legacy of the whaling era when whaling ships would stop at the Azores to add to their crews.”

In 1891, spinner Mathew Cullen, according to Leonard Rebello in Lizzie Borden Past & Present, was “murdered by one of a ‘gang of Italians’” after he “made a profane reference to a half dozen Italians.” Two men were charged and convicted.

Fall River was also the scene of a patricide in 1882 when James McDougall, Jr. shot his father five times. His father did not die, and McDougall, Jr. was sentenced to prison for only six years. As luck would have it, after his release, McDougall, Sr. died and James was sentenced to an additional six years for his crime.

No other crime compares in scope or notoriety with the murders of Andrew and Abby Borden—and the Fall River police’s investigation into this case has been the subject of analysis, review, and scrutiny, for both its successes and failures.

Much of the Fall River Police Department was away from Fall River on the day of the Borden murders. The FRPD had been taking an annual excursion to Rocky Point, an amusement park in Rhode Island, and that was where four-fifths of the force was on August 4, 1892. Was the fact that these double murders were committed on that day simply a coincidence? Probably. However, it also seems at least possible that whoever committed the crimes knew about the excursion that was scheduled and timed the slayings to coincide with it.

Edward Rowe Snow in Piracy, Mutiny and Murder, writes: “It is said they [the police department] have not had a similar excursion since.” However, Rebello points out that this does not appear to have been true, as an 1893 item in the Fall River Daily Herald reported that there was an excursion the next year, but that most police officers remained in the city while only members of the night patrol went to Rocky Point.

Top cops who investigated the Borden butchery

The Fall River City Marshal (“Marshal” being the title of the head of the police department) in 1892 was Rufus Bartlett Hilliard. He had grown up being moved from place to place. However, this lifestyle had not been fueled by adventure, but made necessary by tragedy. Hilliard was born in 1850 in Pembroke, Maine. When Rufus was only two, his mother died. The toddler traveled to Pennsylvania to be cared for by his grandparents. When they died, the boy went to live with an older sister in Newburyport, Massachusetts. Still later, for reasons unknown, the growing boy went to live with another older sister in Newcastle, New Hampshire. In 1865, at the age of fifteen, Hilliard enlisted in the army. His tour of duty up, he went to Lowell, Massachusetts, and studied mechanical engineering. In 1874, he traveled to Fall River to work at the American Print Company.

Hilliard apparently decided on a career change in 1879 when he entered the Fall River police force. His work as a police officer must have impressed his superiors, as he became a sergeant three years later in 1882. Four years after that, he was appointed Fall River City Marshal. During his tenure in that position, he would deal with Fall River’s most famous unsolved murder case.

In 1888, Hilliard married Nellie Clark, who taught sewing at the Fall River Technical High School. A son, named Dana S. Hilliard, was born in 1889.

Marshal Hilliard played an extremely prominent role in the Borden drama. Hilliard led the search of the home that took place on the Saturday after the slayings, August 6, 1892. Marshal Hilliard accompanied Mayor John W. Coughlin when he informed Lizzie the same evening that she was suspected. The shoes and stockings of Lizzie Borden were placed in the custody of Marshal Hilliard on Monday, August 10, and returned to him after being examined by doctors. On August 11, Hilliard was the officer who arrested Lizzie for the murder of Andrew J. Borden.

Hilliard remained as Marshal until 1909. He died in 1912.

In 1989, a gift of Marshal Hilliard’s papers was made to the Fall River Historical Society. The donor was Donald A. Bradbury, whose late wife, Jean Bradbury, previously Jean Hilliard, was Marshal Hilliard’s granddaughter.

Fall River’s Assistant City Marshal in 1892 was John Fleet. Like so many Americans, and as noted especially typical of Fall River residents in the period under discussion, he came to this country from foreign shores. Born in Lancaster, England, in 1848, Fleet immigrated to the United States. When Fleet was first in this country, he worked in American Linen Mills. In 1864, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy, and served in the Civil War. After completing his military service, he worked at the Fall River Boiler Company. Fleet appears to have been someone of varied interests and talents as he had also worked as a painter and house decorator.

In 1877, Fleet joined the police force. Six years after he was appointed, in 1883, he was made a sergeant. He rose to Assistant City Marshal in 1886.

At Lizzie’s trial, Assistant City Marshal Fleet testified that Lizzie gave him the following explanation for her whereabouts when her father was murdered: “She then went into the dining room to her ironing, but left, after her father was laid down, and went out in the yard and up in the barn.” He further testified that Lizzie “said she remained up in the barn about a half an hour.” He also testified about finding the famous handle-less hatchet that might have been the murder weapon.

Fleet succeeded his boss, Hilliard, as City Marshal in 1909.

Fleet was married to Lydia Wallace. Four sons and a daughter were born during their marriage. Fleet was a member of several fraternal organizations including the Richard Borden Post, the latter once again reminding us of how prominent the Borden name and family was in Fall River. Fleet died of a heart attack in 1916.

Like John Fleet, William H. Medley was an immigrant from England. Born in that country in 1853, he came to the United States with his family in 1869 when he was sixteen. The Medley family settled in Lowell, Massachusetts where young William found work in a textile mill. He came to Fall River in 1876 where he worked in a mill. During this time he was active in the Mulespinner’s Union and wrote for a union publication appropriately titled The Labor Standard.

Medley joined the Fall River Police Department in 1880. Rebello writes, “One of the first important cases in which he appeared as a witness was the Borden case; several phases of which were investigated by Officer Medley.” He was promoted to inspector with the rank of Lieutenant eight months after the Borden trial. He was appointed Assistant City Marshal in 1910. He became the first Chief of Police in 1915—the title that had succeeded the title of “City Marshal.”

Along with wife Mary and daughter Kathleen, William H. Medley was involved in a serious automobile accident in 1917. Medley died three days afterward. Mary and Kathleen survived the accident.

Captain Philip Harrington was a true son of Fall River, having been born in that town in 1859. He was part of the working world from a young age—as a boy at his father’s grocery store and as a messenger for Western Union Telegram. He apprenticed as a cabinetmaker at Borden & Almy for three years.

In 1883, Harrington joined the Fall River police force. He became a Captain ten years later. He testified at the preliminary hearing and trial as to his investigation the day of the murders.

Harrington was married twice. His second marriage was to Kate Connell and took place on October 11, 1893. He died less than three weeks after the wedding at the age of thirty-four.

Fall River Police Headquarters

At the time of the Borden slayings, the headquarters of the Fall River Police was known as the Central Station. It was a large granite structure, located on what was then called Court Square, in walking distance from Second Street. Judge Josiah C. Blaisdell’s inquest and preliminary hearing on the Borden murder case were held there. It had been built in 1843, but not as a police headquarters. It had been called the Richardson House and came equipped with a large stable. In 1857, at the suggestion of Mayor Nathaniel B. Borden, Fall River bought the building to house police headquarters and other municipal departments.

The city had the building remodeled so it could serve its new designated functions. Prominent among those helping to renovate it was Southard H. Miller, the man who built the home at 92 Second Street in which the Borden murders were committed.

The police building was remodeled a second time in 1874.

When the Court moved to Rock St. in 1911, the police station remained and expanded to take over the whole building. In 1916, they moved the Police Headquarters to the corner of Bedford and High Streets.

The FRPD website reports that construction of a new police headquarters began in 1996 and was finished by 1997. The FRPD is currently headquartered at this new building at 685 Pleasant Street.

Like many other law enforcement agencies, the Fall River Police Department faced special challenges when the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, banning the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages, was passed in 1919. A Prohibition Squad was formed especially to deal with these offenses. Presumably, the officers in it either received other assignments or had to look for new avenues of employment when the Twenty-first Amendment, rescinding the experiment in prohibition, was passed in 1933.

Many changes were made over the years as the FRPD changed with the times. Up until at least the 1950s, Fall River police often directed traffic. The proliferation of traffic lights eventually made this duty unnecessary.

On May 30th, 1956, Fall River received a special honor as then-Senator John F. Kennedy appeared in a parade beside then-Deputy Chief Ralph Cruedele.

Today’s FRPD

The contemporary FRPD is made up of: Uniform Division, Major Crimes Division, Special Operations, Staff Services Division, Auxiliary Police, Traffic Enforcement, Traffic and Parking Division, Emergency Response Team, Honor Guard, K-9 Unit, Animal Control, and Professional Standards. The titles of most of these divisions are self-explanatory. Special Operations (S.O.D.) was called the Community Policing Division when it was formed in 1993. The website continues, “Officers from the division worked to form partnerships with the community and brought the community policing philosophy to the city.” Officers in this division work with people and groups in various neighborhoods. They are “charged with identifying current and future neighborhood problems, gathering intelligence, preventing gang violence and recovering firearms in the city.” The K-9 Unit is within the S.O.D. and is made up of human officers and trained dogs (K-9, canine—get it?).

The Honor Guard participates in marching competitions and other special events. The FRPD website states, “In addition to each officer’s duty assignment, each team member volunteers additional time as a member of the Honor Guard Team. . . .These officers train monthly, practicing synchronized marching drills, funeral ceremonies, flag folding and presentation while proudly representing the men and women of the Fall River Police Department.”

The Fall River Police Memorial is dedicated to officers who died in the line of duty. It consists of plaques and statues, commemorating the fallen. The website allows access to these personal stories by clicking on their badge number.

Several special events and projects are undertaken on an annual basis by the FRPD. There is a Thanksgiving Basket Food Drive. Food is collected that includes canned food, food in boxes, and non-perishable foodstuffs. Bins in which to place donations are found in the lobby of the FRPD headquarters during the Thanksgiving season.

The FRPD has an “Annual Scholarship Reception for the Thomas J. Giunta and Richard G. Magan Memorial Trusts.” At these receptions, folks are treated with a buffet and the scholarship checks are presented. Both Thomas J. Giunta and Richard G. Magan were Fall River police officers who lost their lives on their jobs, and are part of the Memorial section.

The FRPD works in the present and prepares for the future. It has come a long way from its origins. However, it has not forgotten the crime that catapulted Fall River to fame. On the FRPD website, City Marshal Rufus B. Hilliard is still identified as “arresting officer of record [of] Lizzie Borden.”

Works Cited

Burt, Frank. The Trial of Lizzie A. Borden. Upon an indictment charging her with the murders of Abby Durfee Borden and Andrew Jackson Borden. Before the Superior Court for the County of Bristol. Presiding, C.J. Mason, J.J. Blodgett, and J.J. Dewey. Official stenographic report by Frank H. Burt (New Bedford, MA, 1893, 2 volumes; Orlando: PearTree Press, 2001).

“Changes to OCC1959 Imputation Procedures.” IPUMS USA. n.d. 9 May 2010. < http://usa.ipums.org/usa/1860_1870_release_notes.shtml>.

“FRPD-Our History.” Fall River Police Department, 2008. 9 May 2010. < http://www.frpd.org/history.html>.

Lima, Alfred J. A River and its City: The influence of the Quequechan River on the development of Fall River, Massachusetts. Prepared for Green Futures, 2007.

Rebello, Leonard. Lizzie Borden: Past and Present. Al-Zach Press, 1999.