by Neilson Caplain

First published in May/June, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

When her mother died, Agnes turned toward the idea of doing a ballet based on the Borden murders. . . . “Very slowly and in frightful psychological conflict I was gradually readied; Lizzie took me over.”

The Fall River Legend, choreographed by Agnes de Mille, was first performed in 1948 at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. It was reprised in 1990 by the Dance Theatre of Harlem, and more recently was included in the 2001-2002 repertoire of the Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre. The prestige of these prominent ballet companies once again affirms that Legend is an accepted fixture in the dance arts, to be played time and again by distinguished companies.

Agnes George de Mille was born in Harlem in 1905, into a family of theatre artists. Her grandfather Henry was a successful Broadway playwright, and her father William C. was a famous playwright and director of theatre and film. Her uncle was Cecil B. DeMille, the director widely known for his epic portrayals, mostly based on the Bible. Of special remembrance are the films The Ten Commandments, Sign of the Cross, and The King of Kings. Other secular extravaganzas include Squaw Man, and The Greatest Show on Earth.

The family moved to Hollywood when Agnes was young. Upon graduation from UCLA, Agnes returned to New York where she struggled to make a living as a dancer. She took part in concerts there and in Europe. In 1932 she moved to London to receive training in ballet dancing at Madame Marie Rambert’s Ballet Club, studying with Fredrick Ashton and Anthony Tudor, who, with her, would later revolutionize the dance world. Agnes visited the United States to take odd jobs, dancing in her uncle Cecil B.’s staging of Cleopatra and choreographing the film version of Romeo and Juliet in 1936.

In 1939 she joined the American Ballet Theatre. Here, in the following year, she created her first ballet, Black Ritual, which was the first ever to employ black dancers. In 1942, for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, she created and danced in her first important work, Rodeo. That ballet so captured its opening night audience that it received no less than an enthusiastic 22 curtain calls.

In the 1940s and 50s, de Mille choreographed some of Broadway’s greatest hits, including Oklahoma! (1943), One Touch of Venus (1943), Carousel (1945), Brigadoon (1947), Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1949), and Paint Your Wagon (1951). Oklahoma! proved to be so successful that several revivals have been staged, most notably in 1979, 1998, and again in 2002.

Oklahoma! revolutionized the art of musical theatre by integrating, for the first time, choreographed songs with the plot in such a way as to advance the story line of the script. Prior to de Mille’s innovation, American musicals used the chorus, music, and dance numbers as breaks in the story, pure entertaining moments not connected to the matter at hand. If one wanted to eliminate the music, the plot would still be understandable. However, after de Mille’s brilliant work with Oklahoma!, musicals would never again disregard the musical numbers as irrelevant to the story line.

When her mother died, Agnes turned toward the idea of doing a ballet based on the Borden murders.

. . . I lost my mother under conditions which were an agony to me, for she had sustained a crucial heart attack when she was alone and helpless. In remorseful grief my creative expression turned to a fumbling attempt at expiation. Very slowly and in frightful psychological conflict I was gradually readied; Lizzie took me over (de Mille, 131).

In order to create Legend, de Mille engaged in extensive research, including a visit to Fall River with her friend, the prominent lawyer, Joseph Welch. de Mille’s own prestige and that of Mr. Welch enabled them to gain a first-hand perspective by visiting the relevant sites and gaining inside and private interviews with those who had knowledge of the crime, were descendants of some of the players in the case, and with those who had known Lizzie when they were younger.

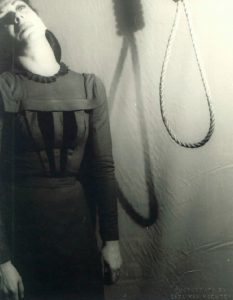

In creating the ballet, she decided to concentrate on Lizzie, Abby, and Andrew. Many of the other participants in the case were eliminated, others assigned to supporting roles. She conceived of the gallows as the principal motif for the set, setting the mood for the dark events to take place. She skillfully crafted the scenes to portray all that forced Lizzie to that dread spot: the mounting jealousy, hate, repressed romance. She also did away with the trial and acquittal, closing the ballet with scenes of Lizzie immured in her house and united “in limbo” with her dead mother.

de Mille was fortunate to have Morton Gould as her music maker. In her book, Lizzie Borden: A Dance of Death, she wrote that Gould came to rehearsals, changed, cut, and improvised his score as dramatic needs dictated. She said he was utterly without pretension, that he helped with good humor in every way he could.

No less fortunate was she to have Oliver Smith as her set designer. His depiction of the gallows made theatre history. Says de Mille in her book:

Lizzie’s house is a transparent skeleton, consisting mainly of uprights and a stair. It is furnished with three rocking chairs, a newel lamp of 1880 vintage, and heavy portieres. These details are realistic and in period. The rest of the set is a mere anatomy. It swings around completely and its back side becomes a New England church; its center platform with rug and curling, wicker chairs pulls forward to the footlights so that the heart of the tragedy can be examined as under a microscope, and is retrieved back into place into its proper complex when the action becomes broader, more general, more formal and less specific; finally, the house tears open, separates, and flies away at the crisis to reveal the rot at the core, the bone, the horror, the gallows (de Mille, 180).

Smith’s credits are noted in any number of Broadway hits, including Rodeo, West Side Story, Brigadoon, Hello Dolly, Oklahoma!, and many others.

A shattering blow was struck when the star of Legend, Nora Kaye, came down with a case of viral pneumonia and was hospitalized with a 106 degree temperature. She was unable to perform and it was necessary to find a last minute temporary replacement for the principal character in the ballet. Alicia Alonso took the part of Lizzie.

In addition to this emergency, says de Mille:

The dress rehearsal for Fall River Legend was held the day of the opening. We were given one hour with set, orchestra, and costumes for a ballet that ran fifty-four minutes. This was the first time that I had seen the ballet put together in straight sequence. There was obviously no time to stop and correct. The extra six minutes were taken in showing the dancers how to manipulate the set, which they do in full view of the audience, putting it together, fitting the gallows into the side, pushing forward to the foots the rocking-chair sector, turning the whole around, back to front, and eventually tearing it apart to leave only the gallows onstage. The handling has to be done to musical count. So briskly did they move that a roar of protest went up from the wings where the stagehands, immobilized by my plan, waited to take over their duties at their usual lethargic pace (de Mille, 212).

At the premiere, from start to finish, there was no applause. But at the end of the performance the audience began screaming. The press reviews were ambivalent but the second performance played to a sold out house.

When Nora Kaye returned to the stage, de Mille said that Nora’s Lizzie “was one of the great acting performances of the twentieth century, and everyone knew it. The applause rolled to her feet like the seas, and it was to do this around the world for fourteen years” (de Mille, 221-223).

The cost of producing Fall River Legend totaled $35,000, not a small sum in those days. de Mille received $1500 for her choreography, Morton Gould $750 and royalties for his music, and Oliver Smith $1000 for his set design. de Mille wrote that the cost of rehearsals always exceeded her fee, just as costs exceeded the composer’s fee. In a fit of pique she said, “I think the whole profession is hell. There’s no money in it and dancers are treated like dogs.”

The Ballet Theatre became a migratory company, and wherever heavy scenery could be transported, Fall River Legend was included in the repertoire. In addition to performances in the United States, the ballet had played in Covent Garden, the Colon Opera, Belles Arts (Mexico), Belgrade, Venice, and Paris.

Throughout the 1950s, de Mille continued a vigorous schedule. She founded the Agnes de Mille Theatre and toured with it all over the country. She appeared and directed on television. She published two volumes of her autobiography. In 1955 she choreographed the dance numbers in the film version of Oklahoma! She also found time to write books about the art of ballet dancing. In those years and in the 1960s, she choreographed several ballet productions.

Fall River Legend was televised in 1956.

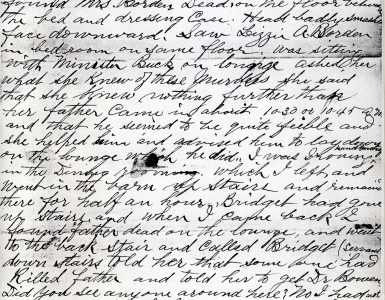

Omnibus presented a realistic recounting of the crime as revealed in sworn testimony, and a condensed reproduction of the trial with Robert Preston as Hosea Knowlton, dignified and lucid, but wearing, to the horror of the great attorney’s daughter, a tweed sport jacket. . . . We rented the real hatchet, and Mrs. Waring’s (the daughter of the defense attorney) grown son escorted it down to New York, guarded it on the set throughout the proceedings, and kept it in the studio safe overnight. The rental was $250 for a twenty-second shot and I doubt if the viewers realized they had seen the actual murder weapon (de Mille, 238).

In the 1960s, de Mille continued to produce many memorable ballets, including The Wind in the Mountains and The Golden Age. In 1968 she published her book, Lizzie Borden: A Dance of Death. She was convinced that Lizzie was the guilty party beyond any reasonable doubt. In the first of two parts of the book, she explains the circumstances of the crime, and in the second part she describes the difficulties encountered in bringing the ballet to the stage.

From 1973 to 1974, the tireless de Mille founded and toured with the Agnes de Mille Heritage Dance Theatre.

This lady was no stranger to adversity. She was forced to struggle for a living in the early part of her career. She endured the death of her mother and husband. She witnessed the desperate and cruel illness of her only son. And she suffered a massive stroke in 1975.

Recovering from the stroke, she continued active participation in her usual pursuits of choreography, television appearances, and writing. She received the Handel Medallion, New York’s highest award for achievement in the arts. Shortly after, she was bestowed a Kennedy Center Honor in Washington, with the President of the United States in attendance, along with other notables in the arts and government.

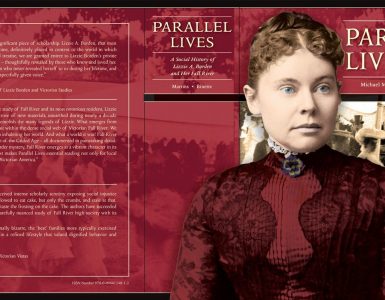

Agnes George de Mille died in 1988. In life, pictures show her as an attractive woman, although in Lizzie Borden: A Dance of Death she wrote that she was not pretty, at least not as pretty as others in her troupe. One picture, taken on the set, which will always remain in our memory, shows her with rather sharp features, hair swept back, revealing a high forehead and business type eyeglasses resting on the top of her head.

Work Cited:

de Mille, Agnes. Lizzie Borden: Dance of Death. Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1968.