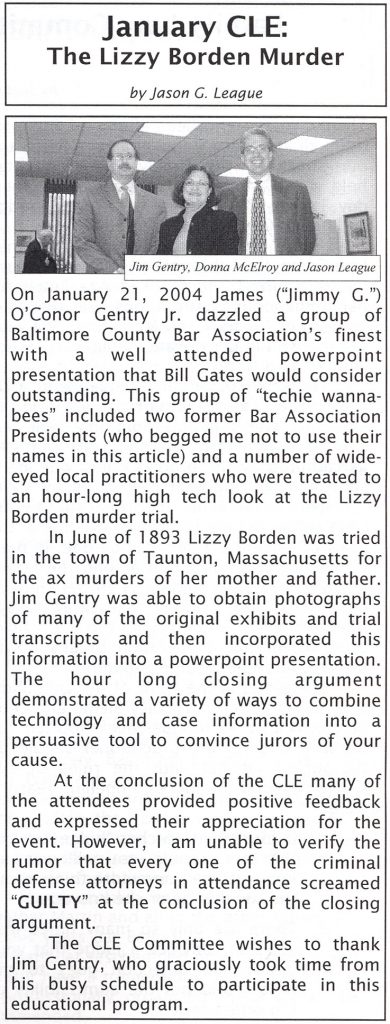

An interview with Baltimore County Prosecutor James Gentry

by Stefani Koorey

First published in April/May, 2004, Volume 1, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Jim Gentry is an Assistant State Prosecutor for Baltimore County in Maryland. In addition to his trial work, he gives presentations on the use of technology in the courtroom to various groups, including the FBI in Washington. His usual audience consists of lawyers who want to improve their trial skills. Jim uses technology frequently in murder cases he prosecutes in Baltimore. To teach this valuable skill, he has researched and developed a closing argument on a famous case using PowerPoint and has argued the case as the prosecutor might have argued it if he had the technology available.

How and when did you become interested in the Borden Murders of 1892?

As a prosecutor for almost 20 years, I have an interest in unsolved murders and cases that remain in the public eye. Although I believe that the Borden murders are not unsolved (Lizzie did it), they remain very controversial. About a year ago I was looking for a new project and I thought this case would prove interesting . . . and so the research began.

You use the Borden case in a very interesting way. Could you tell us a bit about your project?

As you know, I give presentations on the use of technology in the courtroom with emphasis on the use of visuals at trial to persuade the fact finder. The case I have used as an example is State v. Bruno Richard Hauptman involving the Lindbergh kidnapping. I was searching for a new case that I thought would lend itself to a PowerPoint presentation. The Borden Murders fit the bill. About a year ago I started the research and over the course of months I developed a visual closing argument from a prosecutor’s viewpoint. My intent was to present the case as the prosecutor might have presented it in June of 1893, but using 21st century technology. Your web page provided me with a new interest and much of the information I now use.

What kinds of responses do you get from your audiences regarding the guilt or innocence of Lizzie? Is there an overwhelming belief in her guilt or innocence from lawyers you speak with?

I would not say there is an overwhelming belief one way or the other. Although most of my audiences so far are defense attorneys, there are some that have been persuaded by my closing argument. It’s still early in the game for me to get a real sense of how many are persuaded.

Who is your candidate for the murders and why?

Lizzie Borden—because no one else could have done it. Oftentimes in circumstantial murder cases. I look to the defendant’s opportunity to commit the crime and specifically what the defendant told the police—their story. In this case Lizzie not only had the opportunity, but also she gave a number of different stories to a number of different people. In other words, her “story” was inconsistent. To state it boldly . . . she lied. I always ask myself if a defendant didn’t commit the crime why would he or she lie? It shows consciousness of guilt. The attempt to purchase poison the day before (even though not admitted at trial), along with her burning a dress a few days later, coupled with motive . . . her greed . . . convinces me. Common sense also plays an important role. It doesn’t make sense to me that a stranger would come into a house during the day with a hatchet, find Abby upstairs, murder her, and then remain in the house for an hour or two until Andrew comes home and then murder him, all while Bridget and Lizzie are going about their daily business. We can absolutely rule out a stranger. That only leaves Lizzie and Bridget, who were the only ones home that morning . . . and it is Lizzie, not Bridget, who stands to gain by the death of her father and stepmother; it is Lizzie who lied to the police; Lizzie who made up a story about her stepmother receiving a note; Lizzie who attempted to buy poison; and Lizzie who burned a dress and on and on. It seems to me that all other family members were accounted for. In addition, because of the nature and extent of injuries, it is apparent that this crime was one of passion . . . committed not by a stranger but by someone who knew the victims and hated at least one of them. It was certainly overkill. That leaves LIZZIE BORDEN (I know there is more but this is a simple summary).

How would you rate the performance of the various lawyers in this case? (Defense and Prosecution)

It’s kind of hard to tell from the transcript but I believe that the State’s case was very much over-tried. They forgot the old rule of prosecution—“keep it simple, stupid.” The defense did a good job in creating reasonable doubt.

Would you have argued that Justice Justin Dewey recuse himself from the trial for conflict of interest based on the fact that he was appointed judge of the Massachusetts superior court in 1886 by Lizzie’s defense attorney George Robinson when Robinson was Governor of Massachusetts?

There is no question he should have recused himself. It was apparent that he had sided with the defense. His jury instruction sounded as if he were giving a closing argument for the defense.

After studying the case, do you think there is a specific reason why the murders happened on the day they did?

I think it’s possible that Lizzie overheard Uncle John and Andrew discussing a change in a will that might have reduced Lizzie’s share . . . but that of course is a mere guess.

How would you argue the case for the prosecution? What evidence or arguments would you focus on in your side of the case?

I think I answered that above.

And the reverse of that, how would you have argued the case for the defense?

Exactly like they did . . . they created doubt, which is their job.

Do you think the mystery will ever be solved?

It already has been.