by Annette Holba, PhD

First published in May/June, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Are authors who represent Lizzie Borden as a lesbian trying to come to terms with understanding how a Victorian woman could have committed the vicious crimes of murdering a father and stepmother? Why is it that Lizzie must be identified as a “deviant” other in order to explain her crimes?

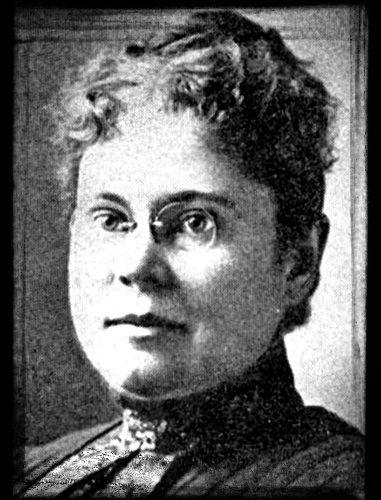

It has been well over 100 years since Lizzie Andrew Borden was charged, tried, and acquitted for the murders of her father and stepmother. Yet, since then, no other investigation, arrest, or conviction prevailed in that legal action. In fact, the mystery that permeates this case is more dynamic than ever. One area in which the Borden murders has been explored (and exploited) is the hypothetical investigation into the sexual orientation of the only person accused of the crimes. Authors who interpret her as a guilty murderer have raised questions as to Lizzie Borden’s lesbian tendencies. Why is it that Lizzie must be identified as a “deviant” other in order to explain her culpability?

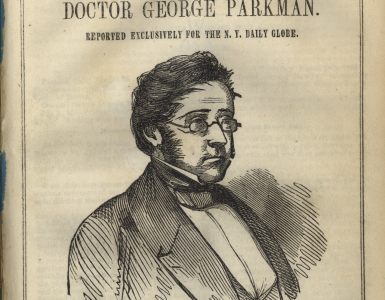

There were hundreds of newspaper articles covering the Borden murders, trial, and aftermath. There were at least forty-three reporters and sketch artists at the trial. Local and national newspapers contained stories about Lizzie Borden and the Trial of the Century. Today, there are hundreds of articles that recount or depict the Borden murders, or theories of what might have occurred. In popular and scholarly venues there are novels, movies, documentaries, operas, theatrical performances, musicals, event re-enactments, and trial re-enactments. Media, and the agendas of those who write for them, has had a profound influence in the shaping of our understanding of the case today.

While there have been diverse approaches to this case, we must consider media and literary outlets that, without provocation, chose to craft a public image of Lizzie as a homosexual by the use of a lesbian “terministic screen” (Burke, 1966, 45).

This essay considers media representations of a homosexual Lizzie Borden as a terministic screen from which one can justify her alleged actions or her perceived guilt. When particular terministic screens are employed in an interpretive process, certain perspectives and intentions are revealed about those employing them. By defining Lizzie Borden through selected terministic screens the interpreter can potentially receive a catharsis as she/he symbolically negotiates social tensions. In other words, authors can be cleansed of emotional tensions through the use of the contextual definitions inherent in the use of particular terministic screens (Burke, 1968). How do these devices keep the Lizzie narrative alive and emergent in new historical periods?

Print media in the Borden murders displayed different terministic screens. One of those screens crafted the notion of Lizzie Borden as a lesbian and thus began the potential justification for this heinous murder. In trying to comprehend how this crime was committed, this forged representation enabled the authors to come to terms with understanding how a Victorian woman could have committed such a vicious crime. In the typical Victorian mind women were weaker than men physically and emotionally. One could not conceptualize a woman responsible for a double axe murder. Instead, in order to excuse a woman committing this murder, she would have to be a “deviant” other – one who is not a typical woman living according to Victorian mores. A homosexual woman in Victorian New England would fit into the category as a “deviant” other. Once depicted as a “deviant” other, Lizzie Borden could be accepted as the author of the crime. In this sense, print media and literary forms helped to establish her potential lesbian nature as a contrivance from which the general population could understand her innate ability to commit the crime.

PRINT MEDIA

In the aftermath of the Borden acquittal, Lizzie and Emma tried to rebuild their lives in Fall River. Instead of living out their days in the house at 92 Second Street, Lizzie and Emma purchased a house on the hill in Fall River, a more affluent part of town. However, their lives again became speculation for town gossip when Emma moved out of the French Street house, as the Boston Sunday Herald reported on June 3, 1905:

Another reported cause of the disagreement was Miss Lizzie’s recent infatuation for stage folk and dramatic matters. The stage was distasteful to Miss Emma’s orthodox ideas and when Miss Lizzie came to entertain a whole dramatic company at midnight hours, it passed Miss Emma’s limit. And right here comes in Miss Nance O’Neil, the well known actress. It appears that Miss Lizzie and Miss O’Neil are warm personal friends. The two women met at a summer resort near Lynn last year, while Miss Borden was passing the vacation period there. A mutual attraction led to the cementing of a close and hearty friendship.

Two days after Lizzie’s death, on June 3, 1927, the Evening Standard reported:

Nurses who knew Miss Borden as a patient at Truesdale hospital two years ago mentioned to their friends, it is said, that she was a woman of decided opinions and will, more masculine in appearance and ways than feminine.

On this same date the New York Times reported:

Lizzie is queer , but as for her being guilty I say ‘no’ and decidedly ‘no’. . . In 1905 Emma Borden left her sister and made her home with friends, the action causing an estrangement between the sisters.

It is evident by these messages in print media that Lizzie Borden stood out from other women in her time. Lizzie was different from most other women because she dared to speak her mind, which is one of the main reasons she was charged with the murders in the first place. It was her statement to investigating officials that caused them to question Lizzie’s relationship with her stepmother, Abby. When asked if she knew who killed her father and her mother [Abby], Lizzie responded, “Mrs. Borden was not my mother; she was my stepmother. My mother died when I was a little girl” (Masterton, 16). In the Victorian era, this statement would not be seen as an appropriate response—it sounds disrespectful toward the stepmother at a time when the utterer should be more concerned with the gruesome death rather than how her relationship with the deceased is perceived.

These print media accounts were not the only references to Lizzie as a lesbian. Two contemporary novels describing fictional accounts of the Borden murders offer a similar depiction of Lizzie as a woman outside of the Victorian Era norm. Elizabeth Engstrom’s story may have been influenced by print media implications, while Evan Hunter’s novel of the case can be seen as a representation of patriarchal values in his depiction of the crimes as sexually motivated.

NOVELS

In Elizabeth Engstrom’s novel, Lizzie Borden (1991), the evolution of the title character as a lesbian is developed. The main focus of the story is Lizzie’s infatuation with a woman she supposedly met while abroad on vacation named Beatrice. This relationship grew more intimate through correspondence between the two women, as Engstrom portrays Lizzie as being ever more infatuated with Beatrice. Her first meeting sounds more like love at first sight:

And then she felt a presence at her side, a peachy presence, and Lizzie looked up into the world’s deepest brown eyes, and the woman asked Lizzie to join her for a refreshment in the salon. Lizzie had flushed a deep crimson, she still felt the blush when she remembered. The woman must have seen or sensed her staring. She looked at the litter at her feet as if it didn’t belong to her and her group and accepted the invitation. . . She felt so terribly inadequate and was quite puzzled that a woman such as this would spend a moment of her time with an American . . . (14-15).

Throughout their period of correspondence, Lizzie demonstrates excitement and anticipation for her new found friend’s letters. Beatrice sends Lizzie a book that she cherished and read daily. Engstrom titled the book Pathways. The book contained a step-by-step program for self-discipline. Later, however, as the novel moves forward, Lizzie has interesting experiences, similar to astral travel, which is the key to how Engstrom depicts Lizzie as the killer. Besides this aspect of modus operandi, Engstrom’s book portrays Lizzie’s relationship with Beatrice as “odd” and a “little dangerous” (37).

Elizabeth Engstrom also provides a rationale for how Lizzie Borden’s name came to change to Lizbeth Borden after her acquittal—Beatrice refers to Lizzie in this way in her correspondence. Lizzie notices the name change and thinks it different, daring, and wonderful. Lizzie secretly wishes “she could be a Lizbeth in true life, and not a Lizzie” (50). While Engstrom’s novel does not explicitly portray Lizzie in a physical relationship with Beatrice, Lizzie does have sexual encounters with other women in Fall River—Kathryn and Enid, Mr. Borden’s mistress. Lizzie’s personality splits when she goes to her now famous visit to the barn on the morning of the murders. It is the “bad” Lizzie who commits the crimes—the murder of Abby occurs as Lizzie masturbates; during the murder of Andrew, Lizzie eats a pear.

Evan Hunter’s Lizzie (1984) also presents Lizzie as meeting a lady she is attracted to while abroad on her 19-week tour of Europe in 1890. This time, Lizzie and her paramour consummate the sexual act, which Hunter erotically describes as liberating Lizzie from her puritanical upbringing. After Lizzie’s return home to dreary Fall River, she finds herself longing for her lover, turning instead to the maid Bridget for lesbian solace. It is this relationship that is discovered on August 4th by Abby, thereby causing Lizzie to react with rage at the intrusion into her privacy—she grabs a candlestick and bludgeons Abby to death.

In a 2002 interview published on LizzieAndrewBorden.com, Hunter explains his idea originated from news pieces that framed the reason for Emma’s leaving Lizzie in 1905 as connected to Lizzie’s interest in the theatre and her friendship with Nance O’Neil (i.e. lesbian actress).

My theory was based on news articles about Lizzie’s sister leaving the house, never to return, never to see Lizzie again, after an argument following the ‘midnight entertainment of Lizzie’s close friend, the actress Nance O’Neill.’ Her sister said in a later interview, ‘The happenings at the French Street house that caused me to leave, I must refuse to talk about.’ And the Reverend A. E. Buck advised her that ‘it was imperative’ that she should ‘make her home elsewhere.’ Emma remarked, ‘I do not expect ever to set foot on the place while she lives.’ I don’t know what all of that may suggest to anyone else, but I do know what it suggested to me.

In his fictional account, Hunter uses the murdering of Abby, in all its ferocity, as a true act of emancipation for Lizzie. It is in retaliation for Abby calling her “Monster” and “Unnatural thing!” that Lizzie swings the killing blows.

She immediately rejected this deformed image of herself, blind anger rising to dispel it, suffocating rage surfacing to encompass and engulf the hopelessness of her secret passion, the chance discovery by this woman who stood quaking now against the closed door to the guest room, the fearsome threat of revelation to her father, the unfairness and stupidity of not being allowed to live her own life as she chose to live it!

Hunter’s patriarchal value system portrays Lizzie’s lesbianism as enabling her to kill, as a violent expression of a right afforded her by her sexual orientation. This depiction of the dangerous lesbian, the “deviant” who acts out her rage against an unjust society, serves as an iconic other, the woman as driven by her lesbian desire. Hunter represents that desire as ultimately murderous and freakish, and compels us to feel the same as we experience Lizzie’s first person lens.

OTHER MEDIA DOCUMENTATION

Multiple other print media outlets addressed the issue of Lizzie and Emma’s estrangement and the relationship between Nance O’Neil and Lizzie. Nance O’Neil was a stage actress whom Lizzie befriended after her acquittal of the double murders. In the Victorian Era, actors were considered more akin to prostitutes rather than artists as we see them today. Lizzie and Nance maintained a friendship and Nance visited Lizzie in Fall River, while Lizzie also attended many of Nance’s performances. In fact, it was reported in several newspapers that Lizzie planned on writing a play, based upon her own experiences, for her friend, Nance.

On June 10, 1927, the New Bedford Standard covered a story specific to Lizzie and Nance O’Neil, nine days after Lizzie’s death. In this report Nance describes her relationship with Lizzie:

When Miss O’Neil played in Boston in 1904 her personality and emotional power so gripped Miss Borden that she stepped out of the bonds of her habitual reserve and sought the acquaintance of the actress . . . They became friends and remained friends, though only in memory, for they never met again after Miss O’Neil finished her season in the East and went on a tour . . . No letters were exchanged in the nearly quarter of a century which has elapsed since Miss Borden and Miss O’Neil bade each other good-by. ‘I am afraid I am a rather poor correspondent . . . We were like ships that pass in the night and speak each other in passing’ (Kent, 345-346).

This interview and reporter’s perspective indicates that the friendship between Lizzie and Nance was short-lived. But from this relationship the speculation of Lizzie’s homosexuality was crafted.

Different print sources identified Lizzie as a potential lesbian. In the Alyson Almanac: A Treasury of Information for the Gay and Lesbian Community, Lizzie is listed as a “suspected homosexual” (Rebello, 431). David Salvaggio suggested:

Lizzie Borden was a miserable and lonely lesbian, tangled in the Victorian web of the late nineteenth century; caught in a man’s world long before women’s suffrage. A kleptomaniac obsessed with materialism, she could no longer bear the frugal father who thwarted the lavish life she desired. And what would her future be if the bulk of the estate went to Abby?

There are multiple documentary films that provide historical record, official interviews, and, of course, potential conclusions of innocence or guilt. For example, Evening Magazine included Lizzie’s case in a segment titled New England Rediscovered; the Discovery Channel aired a documentary on Lizzie Borden in September 1994 titled, Lizzie Borden Took an Axe?; Greystone Communications produced a documentary titled, Lizzie Borden: A Woman Accused; and the History Channel re-released The Strange Case of Lizzie Borden in 2005. While there are many other references to Lizzie Borden that have been viewed in the documentary film industry, these are perhaps some of the obvious representations of our preoccupation with this case. In most of the documentaries, the theory of Lizzie as a lesbian is explored.

There are other theories that tantalize interest in the Borden puzzle. The only perpetrator of such an offense would still be described as a “deviant” other. The Providence Daily Journal posited that Lizzie conspired with another person in the act (Rebello, 123); the Boston Daily Globe reported that a “Frenchman” did it (Rebello, 132). Other theories suggest Dr. Bowen, the family doctor, murdered the Bordens, or Lizzie and Bridget performed the murders (136-137), or that Lizzie committed the act because of an incestuous relationship with her father (140). Another suggested Lizzie killed her parents because Andrew Borden had a love affair outside of his marriage to Abby (373) while yet another provoking theory includes conspiracy within the government itself (136).

There are definite opponents to the perspective that Lizzie murdered her father and stepmother because of a lesbian relationship or simply because she was a lesbian. In 1973 the Fall River Herald News reported on a lecture at the Somerset Lions Club in Somerset Massachusetts by Dr. Jordan Fiore. In that lecture, Dr. Fiore, a resident of Taunton, MA, and a Professor of History at Bridgewater State College, negated the notion of Lizzie as a lesbian, the incest theory, and the idea that she was in the nude when she committed the act. Dr. Fiore suggested if he was a member of the jury he would have found her not guilty too, implying that there was no evidence offered to prove her guilt (Rebello, 387). While multiple theories abound, the fact is that they are theories created in the imagination of their authors who seek to comprehend an incomprehensible situation. In this case, one might ask one’s self, how could this happen to a “normal” person or family? Then one might consider justifying or interpreting the circumstances through a screen that would allow a non-normal event to occur. In this case, one might use the screen of homosexuality to justify the perceived actions of Lizzie Borden as conceivable, if done by a “deviant” other.

Kenneth Burke’s Terministic Screens

Kenneth Burke stated that when he speaks of terministic screens, he has

particularly in mind some photographs [he] once saw. They were different photographs of the same objects, the difference being that they were made with different color filters. Here something so “factual” as a photograph revealed notable distinctions in texture, and even in form, depending upon which color filter was used for the documentary description of the event being recorded (1966, 45).

A terministic screen creates texture and shapes how one interprets the image, event, or picture. Thus, a terministic screen directs one’s attention and also reveals one’s intention. Therefore, consistent with the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (Trenholm, 272) whereby language determines thought, any set of terms that one might use to frame a description to another person acts as a terministic screen that can focus another’s attention toward a particular interpretation or understanding.

Terministic screens are symbols one uses to explain to another or to interpret for one’s self. These screens reveal where attention is being directed and they reveal the author’s intentions at times as well. In the case of Elizabeth Engstrom, her book Lizzie Borden intends to explain or justify why and how Lizzie could have committed the act of parricide. Engstrom herself reveals this in her note to the reader, “My purpose is not to offend; it is to justify” (front matter). In this sense, Engstrom achieves catharsis (Burke, 1968), a way of coming to terms with the inconceivable act of parricide aggravated within a Victorian mindset.

Kenneth Burke (1966) argued that “we must use terministic screens, since we can’t say anything without the use of terms; whatever we use, they necessarily constitute a corresponding kind of screen; and any such screen necessarily directs attention to one field [one way of seeing] rather than another” (50). It is natural to use terministic screens because human beings are symbol-using animals.

Whether Lizzie Borden was homosexual or not, we are always looking for perfection in our interpretive mode. If not careful, this perfected interpretive approach may lead to answers “rotten” with perfection (Burke, 1966, 18). To be rotten with perfection refers to a dangerous and ironic interpretive insight. To be rotten with perfection, according to Burke (1966), is dangerous because meaning is derived from connotations that could be misleading or that could misdirect our pursuit of truth(s). So, while it is admirable to pursue interpretive consummation we can also become rotten with perfection in the ironic sense if we have gone too far. It would be erroneous to conclude there has been a complete examination of Lizzie Borden’s circumstances to a perfection without seeking all potential truths. Terministic screens help to pave the way toward that perfection, while understanding one must still keep a critical eye on the influence of these terministic screens to the construction of meaning.

Each message printed in a newspaper, each literary work that speculates regarding Lizzie’s sexual preference, each documentary that reports and potentially advocates Lizzie’s sexuality as a justification or a scapegoat for the murders is a terministic screen that focuses the reader on that particular perspective and leads one step further toward perfection. Even though today homosexuality is more readily becoming mainstream in our Western culture compared to the status of homosexuality in the Victorian Era, we still seem preoccupied with justifying, excusing, or understanding Lizzie’s potential guilt through a lens that makes her different from other women – or women of the norm. Lizzie was acquitted of the charge of murder for her father, Andrew, and stepmother, Abby. This essay does not speculate on Lizzie’s guilt or innocence. This statement does suggest that others who want to find Lizzie guilty might feel they need to justify her guilt by portraying her as capable of committing crime. In this case, her ethos is crafted outside of the category of “normal” and she is reconstructed as being “deviant” for her time. It is through the label of homosexual or lesbian that media crafts our image of the accused and the crime. Burke might argue that we see all reality through terministic screens and we must learn to be critical of those screens so that we see all of the intertextuality to aid our interpretation. Burke (1954/1984) suggested that our communicative efforts are imperfect because as human beings we use recalcitrant and mystifying symbols that often cause problems inherent in the act of interpretation. Whether we need to justify in our mind how a woman could have killed her parents or whether we want to capitalize on the gruesome story that will make a successful theatre production or film, we still need to consider looking for the truth and the truths connected to this case. This way will enable clearer interpretation of the circumstances.

What does it matter that Lizzie was a homosexual, if she was? What does it matter that after the murders and after her acquittal, she engaged in a lesbian relationship with one woman or multiple women? Why does her sexual preference matter at all? Could it be that Lizzie’s sexual preference is an issue for those who remain fixated in her or his own biases while struggling to understand the act? The terministic screen of homosexuality and Lizzie’s possible lesbianism might guide the author of the theory through an individual catharsis potentially “rotten” (Burke, 1961/1970) with perfection. Through this rhetorical form of keeping the Lizzie Borden mystery unsolved the story is kept alive to be considered through terministic screen after screen. In this rhetorical form we anticipate meaning as our appetite for the story increases. As our appetite builds we seek to satisfy it. The notion of Lizzie Borden as a lesbian satisfies an appetite, creates a catharsis, and helps us to make sense out of the incomprehensible.

Recognizing the rhetoric of Lizzie’s homosexuality portrayed through media as a terministic screen provides a distance necessary for understanding and explanation because it reminds us not to become a victim of mere persuasion or worse, manipulation.

We have attempted to introduce Lizzie Borden to the reader through an account of the circumstances involved in this particular case and demonstrate that multiple media outlets portray Lizzie Borden as a lesbian, or implied the potential for Lizzie to be homosexual. In this case, an understanding of the function of terministic screens, the sociocultural space of women in the Victorian era, and the role of media outlets then and now, suggests that in trying to justify why Lizzie committed this act, opponents of Lizzie’s innocence redefine her as a “deviant” in society. Thus they create her ethos through a terministic screen of homosexuality, which is not so much evidence of her ‘guilt’ as a lesbian woman, but rather it is evidence of the author’s conceptualization of who can commit such a “deviant” act.

1The intended meaning of the word ‘queer’ is to be understood as the meaning consistent with the historical moment of the Victorian Era. In this sense, ‘queer’ is not to be connoted as homosexual, rather, more likely as ‘different’ or ‘odd’.

2While this is not an exhaustive list, there are examples of other reports that surfaced in print media in the aftermath of Lizzie’s acquittal. For a comprehensive list of print media sources, see Len Rebello’s book, Lizzie Past and Present (Rebello, 311).

Works Cited:

Burke, K. (1954/1984). Permanence and Change: An Anatomy of Purpose. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Burke, K. (1961/1970). Rhetoric of Religion: Studies in Logology. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Burke, K. (1966). Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Burke, K. (1968). Counterstatement. Berkeley CA: University of California Press.

Engstrom, E. (1991). Lizzie Borden. New York, NY: Tom Doherty Associates.

Hunter, Evan. Lizzie. NY: Arbor House, 1984.

Kent, D. (1992). Lizzie Borden Sourcebook. Boston, MA: Branden.

Masterson, W. (2000). Lizzie Didn’t Do It! Boston, MA: Branden Books.

Rebello, L. (1999). Lizzie Borden Past & Present. Fall River, MA: Al-Zach Press.

Salvaggio, D. W. (1994). “Whodunit?: A Borden buff’s theory on the crime.” Lizzie Borden Quarterly. 2(2), p. 6.