by Glen “Joe” Carlson

First published in April/May, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

A Tale of Murder, Money, Lies, and Injustice

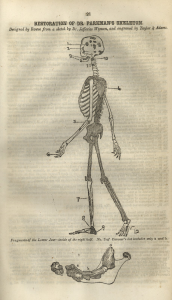

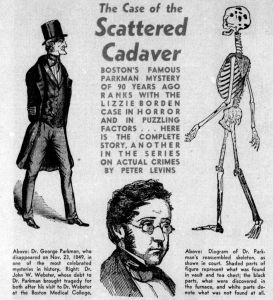

In November 1849, Dr. George Parkman disappeared from the streets of Boston. His mutilated body was found in the Harvard Medical School a week later by Ephraim Littlefield, the janitor at the medical school. Dr. John White Webster, Harvard’s professor of chemistry was arrested for murder because of Littlefield’s suspicion of him. The unfortunate Dr. Webster was tried and executed for the crime in August 1850.

I became acquainted with the Parkman-Webster case in Boston from a used copy of Murder at Harvard1. After reading the book and searching the archives of the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Boston Public Library, and the Internet to find more information about the crime, I discovered Bemis’ transcription of the trial.2 Since then, my library has grown with books, census records, and genealogy about the case. Simon Shama’s book3 was especially revealing, and in July 2003, PBS presented The American Experience documentary, “Murder at Harvard,” based on the book.

I became acquainted with the Parkman-Webster case in Boston from a used copy of Murder at Harvard1. After reading the book and searching the archives of the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Boston Public Library, and the Internet to find more information about the crime, I discovered Bemis’ transcription of the trial.2 Since then, my library has grown with books, census records, and genealogy about the case. Simon Shama’s book3 was especially revealing, and in July 2003, PBS presented The American Experience documentary, “Murder at Harvard,” based on the book.

It may be that Dr. John White Webster was not the murderer of Dr. George Parkman after all, even though the jury found him guilty. Every book that has been previously written followed the events as they were reported in the newspapers and the trial transcripts, and they show that Webster was the murderer.

That may not be the case. There were several things that I found in researching the case to suggest otherwise: Parkman and Webster were friends since boyhood, they had graduated a few years apart from Harvard, and Mrs. Parkman and Mrs. Webster were very good friends. Moreover, Webster’s so-called confession to Rev. Dr. George Putnam is suspect because it was not written by Webster; the letters that Boston’s City Marshal Francis Tukey received, and Webster denied writing, were not in Webster’s handwriting; the newspapers played a big part in the trial; and virtually all key members of the prosecution and jury can be found in the Parkman genealogy. All played a part in a criminal case that had gone too far, until it was too late, to back out. Webster had to be guilty!

Was there a political motivation behind Webster’s arrest and conviction? Collusion? Payoff? Perhaps all three?

Webster’s defense attorney, Pliny Merrick, presented an eloquent and lengthy summation that pointed the finger directly at Ephraim Littlefield, the custodian of the Harvard Medical College.

Webster’s defense attorney, Pliny Merrick, presented an eloquent and lengthy summation that pointed the finger directly at Ephraim Littlefield, the custodian of the Harvard Medical College.

In The Disappearance of Dr. Parkman, Judge Robert Sullivan suspected a Parkman family conspiracy. Sullivan was also convinced that Webster’s “confession” was fabricated by Rev. Dr. Putnam.

Shortly after the trial, A. Oakley Hall wrote an anonymous pamphlet, A Review of the Webster Case, by a Member of the New York Bar (1850). Hall was a Harvard graduate and, in 1868, the mayor of New York City. Albert Borowitz, an author of numerous books and articles on true crime, was fortunate to have found the scrapbook of Hall’s memorabilia in a bookstore. In it, he found Hall’s annotated copy of the Webster trial report, law journals, and newspaper clippings. Hall’s attack was leveled at Ephraim Littlefield and at the defense attorneys who failed to address Littlefield’s lack of credibility. Mr. Borowitz graciously gave me permission to use excerpts from the Hall scrapbook.

I have taken liberties when writing this story and have merged fact and fiction. It is based on a true crime, but the dialog is mine, or was taken from Bemis’ transcript of the trial. I have made an effort to portray the characters as they were. The character of Marshal Francis Tukey is based on fact, as is that of Ephraim Littlefield and the others. While writing this book, I have assumed that it was not Webster who was responsible for Parkman’s death, but, rather, that Ephraim Littlefield committed the murder. However, there is absolutely no concrete evidence that Littlefield had anything to do with the crime. Nevertheless, it could well have happened this way.

In the early morning hours of Friday, August 30, 1850, 50 Boston police officers and 125 invited spectators gathered in the yard of the city jail on Leverett Street. They came to witness the execution of Dr. John White Webster. Thousands more watched the spectacle from rooftops or poked their heads out of windows to see the culmination of the trial that had drawn their attention for the past ten months. Hundreds tried to break through chain barriers that the Boston police had stretched around the prison.

In the early morning hours of Friday, August 30, 1850, 50 Boston police officers and 125 invited spectators gathered in the yard of the city jail on Leverett Street. They came to witness the execution of Dr. John White Webster. Thousands more watched the spectacle from rooftops or poked their heads out of windows to see the culmination of the trial that had drawn their attention for the past ten months. Hundreds tried to break through chain barriers that the Boston police had stretched around the prison.

At 7:30, Rev. Dr. George Putnam, Webster’s spiritual advisor while he was in jail, was admitted by the two guards to the condemned man’s cell, the far corner cell on the right, on the lower floor of the southeastern building.

Two hours later, Sheriff Eveleth summoned to the rear office of the jail the “official” witnesses, read to them the order of events and explained their duties as part of the execution.

“You have been brought here by invitation from me as lawful witnesses of the execution of John White Webster for the crime of murder, for which he has been convicted and sentenced. In a few minutes we will assemble in the jail yard to view his execution. It is my hope that the utmost quiet and good order be maintained, as consistent with the solemnity of the occasion. I request that there should not be any loud talking during the progress of the proceedings.”

With that said, the witnesses were ushered to Webster’s cell, led by Sheriff Eveleth and Deputies Rugg and Freeman. Rev. Dr. Putnam offered a prayer. Dr. Webster knelt in silence, knowing that the end was near. His wife and children were not allowed to witness the execution, nor were they aware that it was to take place that morning.

After the prayer, High Sheriff Eveleth, attended by Deputies Coburn, Freeman and Rugg, Mr. Andrews, the Jailer, Mr. Holmes, the turnkey, and the prisoner, accompanied by Rev. Putnam, left the jail and ascended the scaffolding. The prisoner took his position on the drop. Rev. Putnam immediately entered into earnest conversation with Dr. Webster and continued to do so through the reading of the Governor’s warrant by the Sheriff, and until Jailer Andrews stepped forward to pinion the legs of the prisoner, when Webster affectionately shook Rev. Putnam’s hand, bade him a final earthly farewell, expressing at the same time the hope that they should meet again in Heaven.

Deputy Sheriffs Rugg and Freeman adjusted the rope at 9:35. Before the cap was drawn over his eyes Dr. Webster shook hands with jailer Andrews, Mr. Holmes, and last with the Sheriff and thanked them for their kind treatment.

Deputy Sheriffs Rugg and Freeman adjusted the rope at 9:35. Before the cap was drawn over his eyes Dr. Webster shook hands with jailer Andrews, Mr. Holmes, and last with the Sheriff and thanked them for their kind treatment.

Sheriff Eveleth then broke the silence; in a booming voice shouted, “In the name of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and in accordance with the Warrant of the Chief Executive, I now, before these witnesses, proceed to execute the sentence of the law upon John W. Webster, convicted at the March term of the Supreme Judicial Court, of the murder of Dr. George Parkman.”

The sheriff placed his foot on the spring holding the trap door, and the body of John White Webster dropped eight feet—launched into eternity. Just a few spasmodic kicks, and after remaining suspended some 30 minutes, Drs. Stedman and Clark pronounced the body lifeless. It was lowered into a black coffin, and carried back into his Leverett jail cell to await burial.

John White Webster, Erving Professor of Chemistry at Harvard College, devoted husband and father, witty, fun loving, intelligent, well read, and had not an enemy in the world. He lived in Cambridge at 22 Garden Street, a few short blocks from Harvard College, with his wife, Harriet and three daughters, Marianne, age 24, Catherine, age 22, and Harriet, age 20. His oldest daughter, Sarah, was married and lived in the Azores.4

Webster was born on May 20, 1793, on Fleet Street in Boston’s North End, to Redford and Hannah White Webster, their only child. His family included the earliest Massachusetts settlers.5 His great-great grandfather was William Redford who came to Boston in 1662. His mother’s family settled in 1632, and included Thomas Leverett, the father of Governor John Leverett and the grandfather of Harvard president, John Leverett. Webster’s grandfather was Grant Webster, a successful Boston merchant who owned an apothecary in the North End on Ann Street and, later, in Amesbury, Massachusetts.

In 1807, Webster entered Harvard College. He was awarded his A.B. Degree in 1811, and four years later, his M.D. He interned at Guy’s Hospital in London, England, and after spending time touring the British Isles, he stopped at Fayal, in the Azores where he met Harriet, the daughter of the American Consul Thomas Hickling6 and his second wife, Sarah. John and Harriet were married in 1824, and, after a brief, unsuccessful period of practicing medicine in Fayal, the family moved to Boston.

At first, the newlyweds lived on Ware Street in Cambridge, but soon after their arrival, Webster began building a magnificent new house around the corner on Harvard Street with $40,000 that he inherited from his father.7 He was unable to maintain the huge home for very long, and with mounting debts, gave it up to pay back taxes and moved to 22 Garden Street in 1836.

Webster became a lecturer in chemistry at Harvard (1824-1826), adjunct professor of chemistry (1826-1827), and Erving professor of chemistry from 1827, until his arrest in December 1849. While at Harvard, Webster wrote Webster’s Chemistry8. He was editor of the Boston Journal of Philosophy and Arts and translated Von Liebig’s Organic Chemistry.

While at Harvard, Webster was often the instigator of amusement for the students. They referred to him as “Sky Rocket Jack”9 because of the fireworks he lit for the inauguration of Jared Sparks as the President of Harvard on June 20, 1849. He was also responsible for encouraging the annual dance on Harvard Green for graduating seniors.

Prof. Webster often lectured on the subject of mesmerism, or animal magnetism. It would evolve into hypnosis. In June 1847, broadsides appeared in Cambridge and Boston announcing, “Two Subjects will be Magnetized! A citizen will be put in communication with the Patients. Dr. Webster will Lecture again June 11, 1847, at the Lyceum Hall, and will give the best Mesmeric Entertainment ever produced in this or any other city.”

Prof. Webster often lectured on the subject of mesmerism, or animal magnetism. It would evolve into hypnosis. In June 1847, broadsides appeared in Cambridge and Boston announcing, “Two Subjects will be Magnetized! A citizen will be put in communication with the Patients. Dr. Webster will Lecture again June 11, 1847, at the Lyceum Hall, and will give the best Mesmeric Entertainment ever produced in this or any other city.”

Webster had a collection of rocks and minerals that he proudly displayed in his home and in his lecture room. His interest in mineralogy took him to Sanford, Maine, in the 1840’s, where he prospected for andesine, a mineral of the feldspar group. Webster’s objective was “to acquire what was then some of the finest, if not the largest, terminated vesuvianite crystals”. 10

During his lifetime, John White Webster was a physician, professor, botanist, traveler, rock collector, and chemist, and much more. He was loved by many, considered odd by others; amused his chemistry students with stories; ridiculed for being a spendthrift. He was put to death that morning in August 1850, for a crime he probably did not commit. He was judged guilty for the murder of his friend since boyhood, the wealthy patron of prestigious Harvard College, landlord and moneylender, Dr. George Parkman.

On Friday, November 23, 1849, Dr. Parkman left his home on Beacon Hill to collect a debt owed him by Dr. Webster. The two old friends had decided to meet at 1:30. At 1:30 p.m., Parkman walked into the Harvard medical school building to visit Webster at his lecture hall. According to Webster, he paid Parkman the $483.64 that he owed, and Parkman left the building.

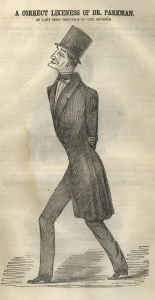

Parkman was never heard from again, although several people testified to seeing him leave the medical school and walking on the streets that afternoon. A hue and cry went out for the missing man. Searches of the Charles River, Boston Harbor, tenement houses, and the medical school produced nothing. The police searched everywhere within a 200-mile radius. Dr. Parkman had simply disappeared. Foul play was suspected, and City Marshal Francis Tukey was in a quandary. The Boston Brahmins demanded immediate answers. One of their own was missing! Dr. Parkman was more than just a man; was one of the elite. His brother was married to Robert Gould Shaw’s sister. Shaw was one of the richest men in Boston, if not all of New England. Why, his brother was Rev. Dr. Francis Parkman, the leading clergyman in New England. And hadn’t Dr. Parkman given large sums of money to Harvard? Hadn’t he given money to build the new lunatic asylum? Everyone on Beacon Hill knew of his unselfish acts. Hadn’t he sold his own land as a site to build the new hospital, the new courthouse, and the new jail?

George Parkman’s family was the epitome of Boston Puritanism. The first Parkman (also named George) arrived in 1640. His great-grandson, Samuel, was the father of George and of Rev. Francis Parkman.11 Samuel was married twice. His first wife was Sarah Shaw and his second was Sarah Rogers. Sarah Shaw Parkman was the mother of six children. Sarah Rogers had five children.

Samuel’s son, George, was born and raised in Boston’s West End amidst the wealthy real estate holdings of his father. The Parkman Market owned by Samuel was a large and prosperous open market where farmers traded and sold meat and produce. Samuel rented stalls to the farmers and traders and became quite wealthy in the process. He built a stately home on the corner of Green and Cambridge Streets that later became the United States Courthouse. When his wife asked him to build the Blake-Shaw mansion, Samuel obliged. On one side it housed their daughter Elizabeth, now Mrs. Robert Gould Shaw, and her family. Mrs. Deliverance Blake, a younger sister, occupied the other side.

George attended Boston Latin School and entered Harvard, receiving his A.B. in 1809, and then attended the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, where he received his MD. He then studied psychiatry under Philippe Pinel and Etienne Esquirol at the Salpêtrière in Paris. He brought Pinel’s theories to Boston which helped spark reform of the Massachusetts mental institutions.

Parkman’s main venture was not in psychiatry, however, especially after being rebuffed for the post of superintendent of the new McLean Insane Asylum. His forte was in real estate and money lending. His property was on the west side of Beacon Hill in the Charles River wetlands, and he owned most of the tenements that housed Irish immigrants and the African-American population.

Parkman’s main venture was not in psychiatry, however, especially after being rebuffed for the post of superintendent of the new McLean Insane Asylum. His forte was in real estate and money lending. His property was on the west side of Beacon Hill in the Charles River wetlands, and he owned most of the tenements that housed Irish immigrants and the African-American population.

Parkman was both loved and hated in Boston. After his murder, some who knew him among the immigrant population remembered him for his kind works. Some were given money to purchase medicine for their sick children, and a few were given leniency for their rent. But most remembered him as a “slum-lord” who demanded that they pay their rent when it was due, a man who was never known to have smiled, and a person whom they would deliberately avoid when they saw him on the street. A news item in the Washington Republic12 proclaimed Parkman as:

…one of our wealthiest citizens. His property is estimated at about half a million. He was in the habit of carrying large sums of money about his person. A gentleman who once went to him for $1000, tells us that Dr. P. answered him by thrusting out his fore-finger, and remarking, ‘There is just the sum.’ On examination, the gentleman found the Doctor had a thousand dollar bill wound round his finger. The Doctor was a large holder of real estate, and had numerous poor tenants, from whom he made his collections himself. He was punctilious in his business habits, but bestowed much charity in an unostentatious way. A politician once stopped him on the street and asked him to subscribe to a fund for firing a salute in honor of some party victory. ‘Just step with me round the corner,’ said the Doctor. Taking him up a dirty alley, through a dark doorway, and up three flights of rickety stairs, the Doctor tapped at the door, which was opened by a wretched, pale-faced child. A poor woman, apparently in the last stage of consumption, was sewing upon a shirt. There was no fire in the stove, although it was a cold March day. ‘Now,’ said the Doctor, turning to the politician, ‘here is ten dollars; you may either fire it away in powder or give it to this poor woman. I won’t attempt to bias you.’ The Doctor darted out of the room and down stairs, leaving the non-plussed [sic] politician standing by the bedside of the invalid. He did not hesitate long as to his disposition of the money—but handed it to the sufferer, and departed a wiser man.

At the memorial service for Parkman on December 3, 1849, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes delivered the eulogy.

He worked while others slept; he walked while others rode. He abstained while others indulged, a man of strict and stern principle with a never flagging energy, simple and frugal. . . .

His gifts and memory shall live in all good actions for which his bounty has flourished the facilities; and if in the world to which he has been summoned, he can look back at this, these precincts, shrouded in gloom as they have been to us, may seem to him only dimmed by passing shadows; and his love, lifted above mortal weakness, still rest over the place which he cherished as Holy Land.13

Parkman’s funeral took place on Thursday morning, December 6, 1849. It began at his residence at No. 8 Walnut Street. Five carriages containing members of the family followed the hearse. Rev. Dr. Peabody of the Stone Chapel (King’s Church on Tremont Street, Boston) was the officiating clergyman. The embalmed remains were placed in a leaden coffin and were temporarily deposited in a tomb under the Trinity Church. The funeral was strictly private, none but the closer relatives attending.14 On May 23, 1850, his body was moved to the family plot at Mt. Auburn cemetery.

A fictional account of the crime and its aftermath, based on fact, is told in my book, The Unfortunate Dr. Webster, available from FarNorthPublishing.com for $19.95, Barnes and Noble, or just email me at FarNorthPublishing.

ENDNOTES:

1 Thompson, Helen, Murder at Harvard, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1971.

2 Bemis, George. Report of the Case of John W. Webster. Boston: Little, Brown, 1850.

3 Schama, Simon. Dead Certainties, Unwarranted Speculations. New York: Knopf, 1991.

4 A daughter, Susan, born about 1830, is on a ship’s manifest, while Harriet is not. This might have been an error, since the birth dates of both would have been 1830. John Langdon Sibley, in his diary, said that Webster, on the morning of his execution, mentioned a son who had died at an early age. No evidence of this child could be found, except in the 1840 Federal census that lists only the name of the head of the household. It shows six girls but no boys: 1 age 5-10, 1 age 10-15, 2 age 15-20, and 2 age 20-30.

5 The Webster family tree is in Webster’s file at Harvard. It is discussed in Sullivan, p. 24. Other family tree data was from Ancestry.com, the New England Historic Genealogical Society, and Jody Glynn Patrick.

6 Thomas Hickling’s first wife, Sarah Emily Green, died in 1778. He then married Sarah Falder of Philadelphia; the ship she was on was wrecked off the coast of Miguel, and he met her when she was rescued. Hickling was one of the wealthiest men in the Azores, and is credited with cultivating the orange.

7 The house was referred to as “The Webster Folly.” It burned down in October 1866 according to John Sibley’s Confidential Notes in the Harvard Archives.

8 Webster’s book became required reading at Harvard and West Point for a time.

9 Sibley, Sullivan, and Sohier refer to the episode.

10 Rockhounds, internet, lists.drizzle.com.

11 The genealogical information about the Parkman family is from the New England Historical Genealogical Society (NEHGS).

12 Reported in The Farmers Cabinet, 12/27/1849, Vol. 48, Issue 20.

13 Holmes was referring to Parkman’s endowment of the Parker Chair of Anatomy, and his “gift” of Cambridge marshland to build a new medical college. Parker realized an extraordinary profit from his bequest.

14 Reported in local newspapers.