by Richard Behrens

First published in November/December, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 4, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

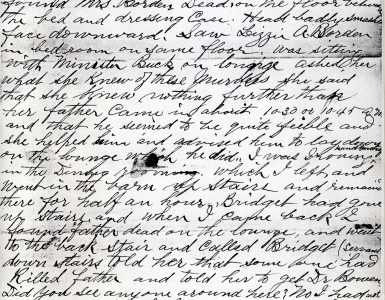

It is now a hundred and fifteen years since the 1892 Fall River murders of Andrew and Abby Borden by person or persons unknown, and in many ways, we are no closer to the truth than we were the day that 32-year old Lizzie Borden was acquitted of the crimes and walked out of the Bristol County Courthouse a free woman. More than a century of research has turned up no physical evidence that implicates Lizzie and no credible scenario has been produced that satisfies all the known facts, but nonetheless the case continues to fascinate and haunt our collective imagination. All who are compelled to peer into this mystery get the seductive thought that perhaps with just a little bit of deductive reasoning, some clever reinvention of the crime, or perhaps a smoking hatchet discovered in some privy excavation, we may arrive at the truth and discover the murderer.

But while we may fail to determine who swung the hatchet that August morning, there is still much to discover about Lizzie Borden herself. After all, she lived for another thirty five years beyond the crime, had neighbors, friends, a staff of servants, possibly an intimate, conducted business, went shopping, invested in real estate, attended the theater, took care of her cars and her garden, fed her squirrels, and read a lot of books. There are a few decades in there during which Lizzie had the opportunity to reveal something about her very private world. But despite her presence in Fall River’s most prestigious neighborhood for more than a third of a century, she was a near recluse and not a single person who worked for her or associated with her, anyone in the position to know intimate details, has talked in all that time. The woman herself remains just as much a mystery as the murders themselves.

A falling out with Emma, her sister, in 1905, and a suspicious friendship with an actress fueled the controversy and the rumors. Lizzie’s inscrutable and murky inner world is wide open for complex interpretations, fit more for the pens of novelists and playwrights than the authors of true crime paperbacks.

Since Lizzie Borden’s entry into the pantheon of offbeat cultural icons, she has been portrayed in the theater numerous times, not just in dramatic plays but also an opera and a ballet. More often than not, she is depicted as being the culprit in the hatchet murders and psychological, often Freudian, readings of her character and subconscious are imposed upon her with a thick trowel. In the 1975 television movie, The Legend of Lizzie Borden, starring Elizabeth Montgomery, the often-debated theme of incest was cemented into the public imagination as Lizzie and father Andrew engaged in gestures and interchanges that were at best co-dependent, at worst stinking of necrophilia.

Other dramatic depictions rarely focused on Lizzie as complex, contradictory and multi-dimensional. Perhaps a person beyond simple interpretation, she was a woman trapped between two ages, halted in time by a horrible crime of which she was accused and may have been innocent, fiercely proud of her position and wealth, compulsively private and haunted by an event that is forever bound to her in history.

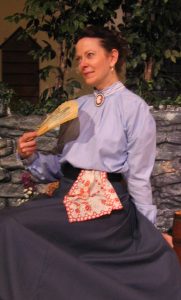

This is precisely the approach that Jill Dalton, a New York actress and playwright, takes with her one-woman show Lizzie Borden Live, which she wrote and performed at the East Lynne Theater Company in Cape May, New Jersey during the late summer of 2007. Dalton enacts a Lizzie such as never before been portrayed anywhere in stage, screen or literature. Her accomplishment may be by far the most accurate, the most thoroughly researched, and the most brilliantly complex Lizzie created for dramatic purposes.

This is precisely the approach that Jill Dalton, a New York actress and playwright, takes with her one-woman show Lizzie Borden Live, which she wrote and performed at the East Lynne Theater Company in Cape May, New Jersey during the late summer of 2007. Dalton enacts a Lizzie such as never before been portrayed anywhere in stage, screen or literature. Her accomplishment may be by far the most accurate, the most thoroughly researched, and the most brilliantly complex Lizzie created for dramatic purposes.

East Lynne’s Artistic Director Gayle Stahlhuth had originally envisioned the theater company as a workshop to rediscover early American Theater, with a focus on the Victorian and Edwardian ages. Increasingly encouraged by the wide tourism of the Cape May area, she started exploring related but more “out-of-the-box” projects. One woman who had fascinated her for years was Lizzie Borden, and she soon contacted Jill Dalton with a commission to write and perform the play.

Dalton was reluctant at first to do a piece about Lizzie. But a few happy coincidences followed, which convinced her that something was guiding her in a particular direction and with research assistance and personal support from both Gayle and director Jack McCullough, Dalton plunged herself into a formal study.

All she had known about the case up to that point was that Lizzie “killed her parents.” She soon discovered that unscholarly true crime paperbacks were useless for research and that she needed to dig at the original source material.

The play takes place on a morning in 1905, the very day that Emma Borden, because of undisclosed irreconcilable differences, moved out of their French Street home, never to see or talk to her sister again. For dramatic purposes, Dalton condenses some temporally distant events such as the alleged theft of art from the store in Providence and a falling out with Nance O’Neil into one day. The play flows nicely in real time, ninety minutes of Lizzie in the wake of her sister’s departure, musing upon her life, her tragedies, her relationships, and the role that society has forced her into.

The play takes place on a morning in 1905, the very day that Emma Borden, because of undisclosed irreconcilable differences, moved out of their French Street home, never to see or talk to her sister again. For dramatic purposes, Dalton condenses some temporally distant events such as the alleged theft of art from the store in Providence and a falling out with Nance O’Neil into one day. The play flows nicely in real time, ninety minutes of Lizzie in the wake of her sister’s departure, musing upon her life, her tragedies, her relationships, and the role that society has forced her into.

The set is divided between a single room in Maplecroft on the right, and Lizzie’s backyard garden on the left. The design is minimal: Maplecroft is represented by a tasteful oak desk with drop leaf revealing various compartments for letters, books, inks and stationary. Combined with a 1905 Candlestick phone, these props reveal a very methodical and business side to Lizzie. She is Lizbeth of Maplecroft, head of the household, a proud and disciplined woman. The various framed pictures of Sarah Borden (Lizzie’s biological mother), her white bearded father, and an affectionately autographed picture of Nance O’Neil, represent Lizzie’s nostalgic side, her strong connection to family—now all gone and departed—and the sad absence of the woman she may be in love with. A third touch on the desk, a round gold Victorian hand mirror, is silently used to demonstrate how Lizzie liked to pinch things.

To the left is the garden, small and tasteful, very English, with a trellis and lots of vines. The most important flower growing here is the pansy, Lizzie’s favorite. The garden has a bench and small table with a silver tray containing a teapot, sugar and creamer, with a cup and saucer. These props give us a sense that we are joining her for tea, and that our visit is quite formal. However, the fact that she is discussing the hatchet murders and occasionally goes off into hallucinatory reveries and panics while she stirs her tea, adds a surreal touch to the proceedings.

Here in the garden she prunes her flowers, feeds her squirrels (most of them named after characters from Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet, Iago and Lady Macbeth), and naively plans her party for Nance. She talks to us out of loneliness and a frustration that she never had her day in court and cannot explain herself. She is at once angry, bemused, in love, outraged, and terrified. Her mind wanders from one thing to another: from the newspaper’s unrelenting slanders against her, to the dark memory of being drugged at the inquest while under the assault of a hell-bent district attorney, from a regression into shock and grief over her father’s murder of her barnyard pigeons, to the hatchet murders themselves and their aftermath. Lizzie lays bare a wide spectrum of her internal emotional life. She expands into a fierce, angry, and prideful woman and subsequently collapses into a scared and horrified child. By holding her own against a hostile community, she exhibits strength and dignity that at one point before the murders, may have seemed beyond her ability. But she is also tormented that the world is not respectful of that dignity—that they continue to cast her in the role of parricide—like the children singing the “forty whacks song” on her front lawn, which effectively contradicts the way she would like to be seen. It is amusing to note that although Lizzie yells at the children to stop singing such an insulting rhyme, she feels compelled to correct them: “She wasn’t my mother. Not 40 and 41. It was 19 and 11. Shoo!” We are tempted to think that Lizzie can make those corrections because she administered the blows with said weapon.

Here in the garden she prunes her flowers, feeds her squirrels (most of them named after characters from Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet, Iago and Lady Macbeth), and naively plans her party for Nance. She talks to us out of loneliness and a frustration that she never had her day in court and cannot explain herself. She is at once angry, bemused, in love, outraged, and terrified. Her mind wanders from one thing to another: from the newspaper’s unrelenting slanders against her, to the dark memory of being drugged at the inquest while under the assault of a hell-bent district attorney, from a regression into shock and grief over her father’s murder of her barnyard pigeons, to the hatchet murders themselves and their aftermath. Lizzie lays bare a wide spectrum of her internal emotional life. She expands into a fierce, angry, and prideful woman and subsequently collapses into a scared and horrified child. By holding her own against a hostile community, she exhibits strength and dignity that at one point before the murders, may have seemed beyond her ability. But she is also tormented that the world is not respectful of that dignity—that they continue to cast her in the role of parricide—like the children singing the “forty whacks song” on her front lawn, which effectively contradicts the way she would like to be seen. It is amusing to note that although Lizzie yells at the children to stop singing such an insulting rhyme, she feels compelled to correct them: “She wasn’t my mother. Not 40 and 41. It was 19 and 11. Shoo!” We are tempted to think that Lizzie can make those corrections because she administered the blows with said weapon.

Lizzie is frazzled in the wake of Emma’s brutal abandonment and ruminates upon her position and the paradoxes of her life. In her inability to be understood and accepted by her sister, she seems to be talking to us as if she were alone and rambling to herself, trying to rationalize and justify everything that had happened since August 4, 1892. For the first time, Lizzie Andrew Borden has her moment in court, able to speak her mind and explain her side of the story. This was something she was denied when she was doped on morphine and confronted with District Attorney Knowlton’s aggressive assault at the inquest in 1892.

Lizzie is continually self-defensive. Commenting on the time when she fainted at the sight of her father’s skull placed on the prosecution table, she points out that the newspapers accused her of play-acting. “First, they say, I have no feelings,” she tells us. “Now I’m play acting. That hurt me the most. Certainly, I do not reveal my feelings in public. I never did. I cannot change my nature now.”

Here we have a Lizzie that we have been waiting to see, complex and ambiguous, at times exhibiting manic depressive hurt and anger, but just as often profoundly sensitive and deeply yearning for a cultured and meaningful life. She is educated and mannered, quoting literature and putting on European accents to throw off the intrusive reporters who constantly call her telephone.

Such ambiguity pervades the performance. Lizzie seems to yearn for our understanding, but she is also trapped in her resentment and hurt, regardless of her guilt or innocence. She constantly tells us that it was impossible for her to commit the murders and goes to great length to exonerate herself, describing in gruesome detail the morphine trip she was on during her inquest testimony and the physical impossibility of her whacking Abby nineteen times without getting so much as a spot of blood on her clothes. But as Lizzie the accused rambles and rages, pleads and rationalizes, Dalton the actress is giving us a wink that Lizzie could very well be lying.

Ms. Dalton has a background not only in acting but also in mime (she had her own mime company in North Carolina in the 1970s), and indeed her performance is very physical. Lizzie prances about the stage, using her body as a wild prop in what comes close to being interpretative dance moves. She swaggers and puffs out her shoulders to portray the policemen who invaded her home in the wake of the murders and cowers as she exaggerates Emma Borden’s meekness as she attempts to confront her dominating sister. And just like a mime trapped in an invisible box would use body movement and hand gestures to help us clearly see the box she is in, Dalton has Lizzie redefine her imprisoning space within Maplecroft to help us clearly visualize 92 Second Street, more than ten years earlier.

Standing in her garden, she points in various directions as if she were back in her bed at the murder house, gesturing behind her to indicate her father’s bedroom, to the right to refer to Emma’s small room, and in front of her, with a horrified shudder, to indicate the guest room where her stepmother was killed. When recounting how she stood in the side doorway waiting for Bridget Sullivan to return from fetching Alice Russell after discovering her father’s body, Lizzie cowers under her garden arch as if the side doorway of 92 Second Street was being drawn from the very air itself. And as Lizzie remembers the actual murders, reenacting them for us as if trying to prove the absurdity of the thought of her being guilty, she moves about the Maplecroft space as if the rooms of the old house are morphing into being through the power of her own memory.

Another aspect of Dalton’s background that aids in her portrayal of Lizzie is her experience with stand-up comedy. That art form indeed lends itself to anecdotal stream of consciousness as the comic wanders from story to story through threaded segues. A phone call from a reporter would remind Lizzie of the press back in 1892 and the unfortunate affair of Henry Trickey; echoes of Lady Macbeth’s cry of “out, out damned spot” would lead to the incident of the pigeon beheading and strikes resonances with the murders themselves and the “flea bite” found on her undergarment by the police. While the story in Lizzie Borden Live is not sequential, it flows from the connections within Lizzie’s mind and leads us through the same incidents repeatedly from multiple viewpoints, much like the layered approach of Citizen Kane’s narrative.

A stand-up comic would also be a master of impersonation, using her voice to portray a wide range of characters, interpreting them through the lens of the comic’s viewpoint. Here we have Lizzie deepening her voice to ridicule the various male players in the tragedy, such as District Attorney Knowlton, who persecuted her and nearly destroyed her life. Through vocal characterizations, she not only brings to vivid life D.A. Knowlton, Emma Borden, her father and stepmother and Nance O’Neil, but we have Lizzie herself impersonating them. Miss Dalton’s performance is a tour de force when she portrays the other characters as mimicked by Lizzie. This strengthens our understanding of how Lizzie Borden viewed her own life and the people who populated it.

The high water mark of the play is certainly when Lizzie takes up an actual hatchet and re-enacts the murders as if she were writing O.J.’s book If I Did It. Her intention is to show us that it was physically impossible for her to commit the murders, but instead she gives us an image of Lizzie Borden straddling her stepmother’s helpless body and administering the nineteen blows to the head that ended the woman’s life. It is a savage and uncomfortable moment, since we actually get a sense of what it is like to swing a hatchet at someone’s head nineteen times. Lizzie delivers the blows, counting off the number of swings, and then goes on to deliver eleven blows to an invisible Andrew. By the end of the demonstration, we are horrified, although it was all pretend and there are no actual bodies.

What horrifies is the image of a desperate and troubled woman who, if she was guilty, is in terrible denial, and if she was innocent, is showing us the moment that shattered her life and destroyed something inside of her, creating a trauma and a wound that would never heal. Either way, guilty or innocent, Lizbeth Borden of Maplecroft was a haunted woman.

Jill Dalton’s Lizzie Borden Live is an accomplishment of not only theater and performance, but of Lizzie Borden scholarship, a tale woven with historical accuracy and intelligent speculation, one that does not try to solve the murders, but to puzzle out the mystery inside the woman herself. It is clearly a personal journey for Jill Dalton who shared a passion with her creative collaborators, and one that deserves serious attention from anyone interested in the American mystery that is Lizzie Andrew Borden.