by Mary Elizabeth Naugle

First published in June/July, 2004, Volume 1, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

I thought I had chosen a simple enough assignment. I would run over to Tyngsborough to track down the famous house where Lizzie Borden slept: the Massachusetts summer home of Nance O’Neil. I would learn what I could about one of the few places known to have welcomed Lizzie in her post trial years. Nothing could be more straightforward.

Nothing could be more wrong. What started as a routine investigation evolved into something much more complicated—expanding into another prominent family’s history with their own mysterious unsolved murder and rumors of a restless spirit. I also discovered that the accounts of all of this would prove as contradictory as Lizzie’s alibi. I should have remembered that, like the weather, all things in New England are subject to change or a healthy difference of opinion. New Englanders are consistent in one thing only—inconsistency.

Those inconsistencies begin with the name of the town itself. It is clearly spelled “Tyngsboro” on maps and city limits signs, but on the facades of the library, town hall, and housing authority buildings, it reads “Tyngsborough”. Luckily, letters are routinely delivered to the occupants of this town with either spelling.

The mail is not routinely delivered to Nance’s old summer home, however. I quickly learned from the Historical Society that the home was lost to urban renewal some thirty years ago. Or was it forty? Anyway, it was gone. But the memory lives on in a file at the Tyngsborough Library, a folder containing photos and clippings about both Nance and the manse. Just as Nance could change her name from Gertrude Lamson, so could the home she so briefly occupied change its name. In fact, the home did her one better and had three identities. It was first known as Tyng Manor, not because it was built by one of the founding Tyngs—it was not—but because it was built on an old Tyng homesite for a wife who was a Tyng daughter: Mary Tyng Pitts.

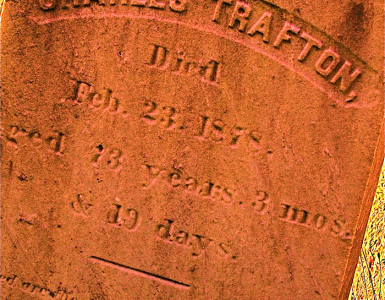

The Hon. John Pitts, who was elected Speaker of the House of Representatives in 1775, built the manor in the 1770s. John and Mary Pitts were early suburbanites, living half of the time in Boston and the other half at Tyng Manor, where she rested at last in a garden tomb west of the manor. The manor remained in the family for three generations, but always happened to pass on the distaff side, first to Elizabeth Pitts Brinley, then to Mary Elizabeth Brinley Kennedy. The other names given the house were Colonial Hall and Brinley Manor. Colonial Hall was a simple nod to the era of its construction, Brinley Manor a nod to the “illustrious and wealthy line” who had merged with the Tyng-Pittses (V.I.A. Annual 5). Apparently the Kennedy family, headed by a modest clergyman of the First Parish Church, was not illustrious or wealthy enough to bestow their name upon the estate.

When Nance acquired the home at the turn of the century, it was referred to as Brinley Manor, the name that has generally stuck. One should note the word, “generally,” for the illustration taken from the 1957 V.I.A. Annual is labeled “Colonial Hall,” although the article is headed “Brinley Mansion.” All of this is very confusing unless you come from around here.

But what’s in a name? Here is a description and drawing of the estate as it looked in 1889, written by the owner—not a Tyng—with an eye toward drawing eager vacationers to what had been converted into a resort, a description that undoubtedly still applied when Lizzie slept there:

Colonial Hall. . . is the most pretentious structure in town [”pretentious” must have been good then], as well as the best preserved of any of the numerous olden-time buildings in the country round about.

No one can visit the place but to be enchanted with its beautiful and commanding outlook, its romantic surroundings and the happy combination of art and nature to produce the most pleasing effects. A century has elapsed since it was built, and yet the massive oaken timbers which entered into its construction so long ago even now show no signs of decay, while the foundations of the imposing structure are just as solid as when they were laid. . . .

Although some changes have been made for the greater convenience and better accommodations of the patrons of the place as a summer resort [indoor plumbing, Lizzie!], the interior of the house, the grand old halls, the spacious apartments with their lofty walls and unique finish, the mantels, the fireplaces, deep window seats, all remain practically unchanged, carrying a sense of wealth and grandeur along with that of the greatest simplicity. There is no gaudiness or attempt at showy ornamentation, yet nothing is lacking to tell that the place was once the home of wealth and refinement.

A double veranda extends around the house, approached from the first and second floors, and affording a broad promenade five hundred feet in length, from every part of which the most enchanting views of land and water are obtained.

A fine carriage-way which enters the grounds through two massive granite gateways from the public thoroughfare a few rods from the foot of the terraces approaches the spacious portecochere in graceful sweeping curves, while a broad walk of asphalt [no gravel here!], with several easy flights of steps, leads from the central gateway up over the terraces to the main entrance. The place is shaded everywhere by the stately old elms and oaks that have attained enormous size and height [two] (V.I.A. Annual, 1 and 5).

Here the writer, perhaps a railroad man himself, expounds at some length upon the railroad running beneath the road skirting the river, making even that distraction into a virtue, with its “splendid roadbed” alongside the Merrimack River, which “propels more machinery than any one stream on the face of the earth.” Nature and machine race romantically forward toward the bright future of a progressive age. He continues:

The Merrimack between Lowell and Nashua is practically an elongated lake; the water is deep—in some places forty feet or more, and regular trips are made daily during the summer season by staunch and capacious steamers between the two cities . . . beside the specials for moonlight excursions. Crowds come on these boats for a pleasure outing at Harmony Grove, which is beautifully located on the river’s bank, near the east end of the iron bridge. Frequently bands of music are brought along, and as they pass and re-pass Colonial Hall, with their decorations of bunting and colored lights, it goes without saying that the scene is full of beauty and inspiration (V.I.A. Annual, 1 and 5).

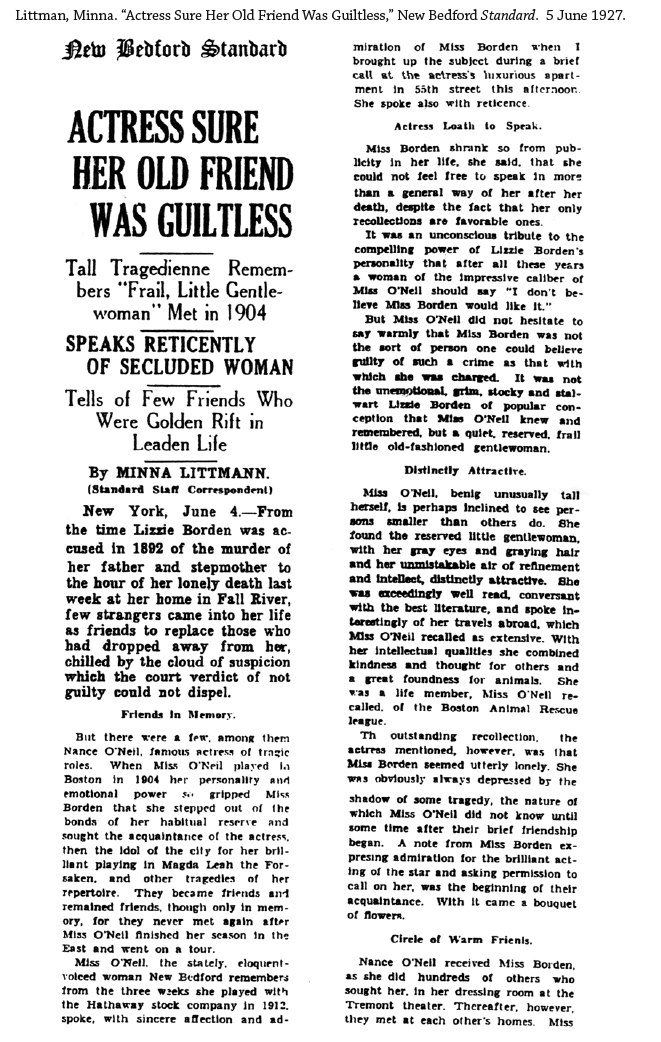

Imagine Lizzie reading these words at 92 Second Street in 1889. It was probably a description to die for (or kill for). The gaiety and splendor described here were for paying tourists, not honored guests in a private home, and honored guest she would be in the summer of 1904. The only description we have of that visit comes from Nance in an interview for the New Bedford Standard, 4 June 1927, in which the actress recalled the recently deceased Lizzie. The purple prose of the reporter dubs their friendship a “golden rift in leaden life,” a phrase the staff correspondent was so proud of that she used it three times with various wordings. Still, between such painful phrases and the gushing descriptions of the actress’ garb (“the shadow of [a] great black hat. . . shaded her face, cameo-like above a clinging black gown, illuminated by a single vivid scarlet tassel hanging from the waist”) and decorating taste (“. . . flicking an ash from her cigarette into a tray of a red Chinese laquer stand—gorgeous Chinese laquer and carvings, embroideries and jade dominated the whole room”), we are given a completely new picture of Lizzie, one that contradicts all the descriptions of the dull and homely spinster. Nance, the paper relates, “found the reserved little gentlewoman, with her gray eyes and graying hair and her unmistakable air of refinement and intellect, distinctly attractive. She was exceedingly well read, conversant with the best literature, and spoke interestingly of her travels abroad, which Miss O’Neil recalled as extensive. . . . qualities she combined [with] kindness and thought for others . . . She was obviously always depressed by the shadow of some tragedy, the nature of which Miss O’Neil did not know until some time after their brief friendship began.”

This last claim seems highly unlikely unless Miss O’Neil had cut straight to the theatre reviews in the papers of 1892 and 93, but an aging actress trying to keep afloat in Hollywood just three years after the Fatty Arbuckle trial—an event that put many an actor on the straight and narrow path set by the Hayes Code—must be careful what she said about her friendship with a woman of Lizzie’s notoriety. That caution may be behind Nance’s denial that “she had spent some time at the Borden home in Fall River, or that she had ever met Miss Emma Borden”—a denial she contradicts earlier in the interview by saying that after their first meeting, she and Lizzie “met at each other’s homes.” Nance does proclaim her belief in Lizzie’s innocence and confirms that “Miss Borden was once a guest for a few day[s] at her country place at Tyngsboro” before lapsing into cliché: “We were like ships that pass in the night and speak [to] each other in passing.”

So just how chummy were Nance and Lizzie? It is hard to say. No matter what Nance recalled in 1927, we know that she played in Fall River the autumn of 1904, and the Maplecroft house party for Nance and her troupe seems to be well documented in Fall River (Rebello 309-311). Given the state of Nance’s finances (usually precarious), she may well have welcomed the hospitality of the star-struck heiress and merely reciprocated by inviting Lizzie to be a wallflower at Brinley Manor for a weekend in the off-season. Or perhaps their friendship was genuine, though brief. Either way, when Lizzie visited, she at least had a tub, a fine view, and a change of air.

But what of a murder and the ghost of Brinley Manor? Well, they are part of Tyngsborough folklore, and the ghost has the unique habit of haunting not a place, but a family. The details are confusing, but they surround the death of an unnamed beauty, the beloved of some past and unnamed Tyng. She was supposedly found most cruelly slain in a room at one of the old Tyng homes. (Franker modern versions have the unsuitable sweetheart dying at the hands of an abortionist.) When the errant Tyng died, she filled the home with banshee wails and appeared at the head of the bed as he expired. She popped up on the grounds thereafter, glowing in unearthly fashion, with ashen face and wild black hair. A capricious ghost, she at some times terrified laborers with her shrieks as they passed the home and at others, guided strangers and even provided food and shelter to a woman caught in a storm. When the home was abandoned and crumbled to the ground, the wraith moved on to another Tyng home—the Tyngs were prolific builders—where she limited her activities to the parlor of the left wing (Lowell Sun).

And there she remained until it came time for Nance O’Neil to liquidate. Nance, notoriously bad at managing money, is believed to have needed ready cash in 1907 (Lowell Sun). However, just as she would twenty years later, Nance turned tragedy to good account by calling the papers for the best piece of free publicity of her life. Brinley Manor, after all, was built for a Tyng, so Nance conveniently found that the restless spirit had taken up residence. The shaken actress, propped up by sympathetic reporters, managed to gasp out the details:

From the moment I started to live at the manor, . . . I felt oppressed. . . I began to [hear] strange knocks and then came groans and other weird noises. At night the walls of my bedroom resounded with unexplained rappings. . . . Finally came my most terrible experience. I saw the ghost come out of one of the rooms on the first floor as I turned to ascend the stairway. Looking up, I saw at the top the figure of a young woman with long unbraided glossy hair. The sight froze me in my tracks. I tried to shout, but could not. Overcome with weakness, I sank on the stairway. When I looked up, the figure was gone (Lowell Sun).

Guests also had complained of noises and sightings of a “white draped wraith.” Nance permitted the spirit one encore the day she returned to settle her affairs: the ghost appeared and an hysterical Nance fled the house—or so said Nance.

The last owner of Brinley Manor was the Academy of Notre Dame. The ultimate fate of the building was surprisingly blurred already in the memories of Tyngsborough citizens. According to several residents, the manor, against the wishes of town preservationists, was bulldozed in the dead of night in the late sixties, or maybe the seventies. Or else it burned. I was directed to the site, unmistakably marked Brinley Terrace, where the Housing Authority office and a development for senior citizens now stand. I had been told that Mary Tyng Pitts’ grave remained, surrounded by a picket fence. After some wandering, I asked two lady residents if they could direct me, which indeed they could. They referred to it as “the crypt” and pointed the way to what remained of Mary’s garden. Her garden does not grow well, and the crypt could easily be mistaken for a root cellar. In fact, I learned at the office that many think it is a root cellar. Nonetheless, I was referred to the oldest member and last word of the Housing Authority, who informed me that the house burned in the seventies and that the crypt lies safe beneath the protective door.

And that, I have decided, is enough. For, in the end, it is not the dates or details that matter in this story. What matters is how a town—any town—makes tall tales of its history, creating its own cursed House of Usher. While editing this story, it occurred to me that the changes in names, spellings, dates, and details are just their way of editing oral tradition.

I toyed briefly with the idea of returning to Brinley Terrace to lift the unpadlocked doors and look for some inscription, but thought better of disturbing Mary. For although the shabby doors seem a poor epitaph, they protect her from a world of prying eyes far better than do stones rubbed raw by chalk.

Works Cited

“Brinley Mansion,” V. I. A. Annual Tyngsborough-Dunstable Historical Society. April, 1957, 1 & 5.

Littman, Minna. “Actress Sure Her Old Friend Was Guiltless,” New Bedford Standard. 5 June 1927.

“The Many and Queer Pranks of a 100-Year-Old Ghost Startle Bay State Town,” Lowell Sun. 1907.

Rebello, Leonard. Lizzie Borden: Past and Present. Al-Zach Press, Fall River, MA, 1999.

Photos courtesy of Tyngsborough Public Library.

Many thanks to the helpful people of the Tyngsborough Historical Society, Public Library, Town Hall, and Housing Authority.