by Eugene Hosey

First published in Winter, 2013, Volume 8, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Michael Thomas Brimbau, Fall River native, poet, and first-time novelist, probes the mysteries of the legendary Lizzie Borden and provides a very original solution to one of the most baffling crimes in history. The infamous woman Lizzie Borden who lived out her life in Fall River where she had been accused of killing her father and stepmother has left us a great unsolved crime. The silence of Lizbeth Borden in the post-trial years has been remarkably strange, spooky, and perplexing. Surely she could have given us the solution. She told us nothing. There is something fascinating about a woman whose humanity and real identity have been so successfully hidden. She is as unyielding and Sphinx-like as the murder case from which she derives her fame.

Michael Thomas Brimbau, Fall River native, poet, and first-time novelist, probes the mysteries of the legendary Lizzie Borden and provides a very original solution to one of the most baffling crimes in history. The infamous woman Lizzie Borden who lived out her life in Fall River where she had been accused of killing her father and stepmother has left us a great unsolved crime. The silence of Lizbeth Borden in the post-trial years has been remarkably strange, spooky, and perplexing. Surely she could have given us the solution. She told us nothing. There is something fascinating about a woman whose humanity and real identity have been so successfully hidden. She is as unyielding and Sphinx-like as the murder case from which she derives her fame.

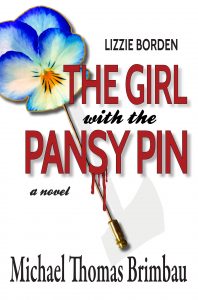

The Girl with the Pansy Pin is a sprawling exploration of the life of Lizzie Borden before and after the murders as both imagined and understood by available facts. This is not another tired edition of a story that begins with the shocking murders, followed by legal consequences and the suspense of did she or didn’t she?—ending with a solution to the mystery based on some piece of deduction that is supposed to be clever but is really very flawed for those well educated in the case records. Nor is the story used as a basis for cheap sensationalism or paranormal horror that has no respect for the case facts or interest in historical or human truth.

At a length of more than 500 pages, Brimbau’s version of the Lizzie Borden story is an ambitious work covering a lot of territory. The novel is, of course, about a double homicide in Victorian America and the controversial acquittal of the accused. It is a fictional biography of Lizzie Borden, a very personal realization of the woman. Unlike an earlier Fall River native, Victoria Lincoln, author of A Private Disgrace, Brimbau does not pretentiously claim a wealth of insider information or convince himself that he is writing truth and then present theories full of holes. Brimbau writes about Fall River with an historian’s sensibility, describing the mills; the hostility between the mill workers and the upper classes; the town’s streets, bridges, and fishing spots; and the various daily activities of the population.

Brimbau is a very visual writer and demonstrates a love for writing description. He frequently puts three adjectives before a noun, but the adjectives are not redundant. A typical critique might advise cutting some adjectives, but the piling of adjectives works more often than not. Brimbau’s style indicates an earnest goal to capture atmosphere, the tone and character of a thing, and make it feel real. I recall noticing in the first chapter how the wealth of description was giving me vivid mental pictures and successfully conveying sensations. I was engaged by poetic observation. A charming example is in the treatment of winter weather of New England: “All up and down Second Street one could discover a mystical white beauty. The craggy limbs and crinkled trunks of leafless trees gave up their lumpy clumps of snow to a stream of sunlight that pierced a clearing sky. Jagged icicles hung from rooftops and gutters on nearby homes. They melted and trickled, like clear dribbling saliva on a dinosaur’s crystal teeth.”

The murders and trial happen just after the middle of the book. And thankfully the author does not force upon us a retread of Trial Q&A. Rather, he uses most of the courtroom chapter to give the reader images of Lizzie Borden according to the newspaper reporters of the day. Interestingly, her hair and eyes are seen as different colors by different people. There are different opinions as to whether she is attractive; apparently no one believes she is a great beauty. One observation about her countenance is fairly consistent: People seem impressed by a dull stony face that can also be unexpectedly expressive.

Brimbau spends most of his time on people and personal relationships. The principal characters are not flat but drawn in detail. Andrew Borden is as bad as anybody could expect – not just stingy and rude but hateful and completely closed. Abby is unremarkable except for her pig-like ways and her constant caution not to oppose her husband. Emma is very conscious of propriety; she fears her father—for good reason, as we come to learn later in the Maplecroft years when she finally tells Lizzie a cruel, sad story of lost love. Bridget sometimes lies and does what she shouldn’t but is terrified of the old man. Morse has a gross habit: He likes to carve the calluses off the palm of his hand, to the point of drawing blood. In one scene taking place in the barn, Morse makes a pass at Lizzie. Dr. Bowen prides himself on being very much the scientist. He shows dry wit when he examines the dead Abby Borden, making the remark that someone was “cross” with this woman. And there are several minor characters—each with an idiosyncrasy.

Lizzie, of course, is the main character and is fleshed out more in this novel than in any other. It must be said that the over-arching nature of Brimbau’s Lizzie Borden is that she is enigmatic. Her character is a collection of so many things – incongruous attributes in moral opposition. But it cannot be said that there is anything wish-washy about her. She seems possessed by an ineffable intensity. She is temperamental, audacious, determined, liberated, adventurous, passionate, dangerous, and capable of true hatred. She disparages the restraints of her time. Even though she craves the finer things of life and fantasizes about wealth, she recognizes the ridiculous pretensions of the ignorant wealthy. She has no prejudices about the lower classes when it comes to her most personal involvements. One gets the feeling that Lizzie would try anything at least once. I can see Brimbau’s Lizzie having a great time embracing the liberating changes in American society of the 1960s. Lizzie is no snob. She’s individualistic—and yes, we realize there is something out of kilter in her head when we reach the end of the story. The last sentence of the book is strikingly eerie. For all that is revealed about her, she is still an inscrutable phenomenon.

So did Lizzie do it or was it somebody else? That simple question cannot be answered. Characters do some strange things. In a sinister conversation, Morse points out to Lizzie that there are people who can be enlisted to get rid of enemies. Bridget hides a bloody axe on the morning of the murders. The dress Lizzie burns in the kitchen is indeed bloody. Lizzie is observed pouring the contents of an envelope into some kneaded dough. And Brimbau has created a mystery character—a young Irish man who knows both Bridget and Lizzie; he is essential to the novel. But the story is not marred by disrespect for the facts of the case. Exactly what did happen according to The Girl with the Pansy Pin will pretty much fit logistically within the parameters of the official record. I don’t want to give away the ending of a new book and spoil it for readers; I highly recommend it. The author has worked hard to give us something fresh. Compared to previous authors such as Engstrom and Hunter, Brimbau’s canvas is larger and painted with multiple themes.