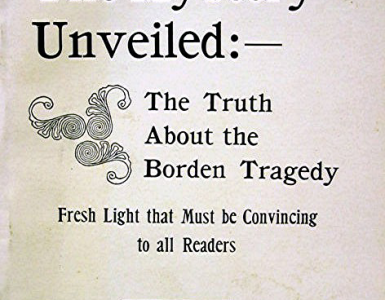

by Eugene Hosey

First published in Fall, 2009, Volume 6, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

An Impossible Crime

Knowlton begins his summation with an acknowledgment that this is a painful case, that the crimes in connection with the identity of the accused, together with the duty of the jury—“there is that in it all which lacerates the heartstrings of humanity.” He calls it an incredible crime and speculates about the improbability of it. Knowlton wants to condition the jury against the expectation of seeing an image of an axe murderess in the visage of Lizzie Borden, to understand that this guilt doesn’t show: “It was a terrible crime. It was an impossible crime. But it was committed. And very much, very much, Mr. Foreman, of the difficulty of solving this awful tragedy starts from the very impossibility of the thing itself.” He describes the crime as a thing believable only in fiction and yet it was committed—an observation that resonates today after a century of study. It is deeply perplexing as to whether Lizzie is guilty or innocent. Knowlton then goes on to show by examples how neither gender, nor age, nor reputation has ever been a guaranteed virtue that renders anyone incapable of a brutal crime.

Circumstantial Evidence

Without direct evidence against Lizzie, Knowlton’s case is based on circumstantial evidence, and he is aware of the popular notion that circumstantial evidence is unreliable. “I speak of it frankly, for many honest men have been heard to say—I have heard many an honest man say that he could not believe circumstantial evidence.” He makes a literary reference to illustrate how powerful a single piece of circumstantial evidence can be: When Robinson Crusoe discovered the footprint in the sand, he knew he was not alone on the island. He continues to prepare for the presentation of his case by expanding on his explanation of circumstantial evidence. He defines it through the use of the analogy of a flowing stream. One can see the direction of the flow by an observation of the refuse that floats upon it. Some debris may go here or there, but the vast majority runs in the same direction. He asserts that eye witness reports are often less reliable.

Malice Against Abby

“It was the malice against Mrs. Borden that inspired the assassin. It was Mrs. Borden whose life that wicked person sought; and all the motive that we have to consider, all we have to say about this case bears on her.” As he delves into Lizzie’s hatred of her stepmother, Knowlton is expounding on what may fairly be called the soul of his case against Lizzie, for without this it is not possible to believe in Lizzie Borden the assassin of parents, regardless of the circumstantial evidence arrayed against her. At least, this is what Knowlton has reckoned. The irony of his case is that while he claims the Prosecution does not need to prove motive, he actually spends a great deal of time on matters connected to it.

Knowlton paints a picture of a quarrelsome, embittered household where animosity festers and volatile anger must be constantly suppressed. He uses every kind of evidence available to him to demonstrate Lizzie’s murderous hatred of Abby – the refusal to call her Mother and the resentment over Andrew’s financial assistance for Abby’s relations; the remark to the dressmaker, calling Abby a “mean, good for nothing old thing;” the correction made to the officer who referred to Abby as Lizzie’s Mother.

Knowlton claims that the wounds in Abby’s skull indicate the work of a woman. “The hand that held that weapon was not the hand of masculine strength. It was the hand of a person strong only in hate and desire to kill.” Interestingly, the Defense would make the opposite argument. Knowlton’s contention about the nature of the axe wounds is actually based on a very subjective interpretation. This is a case of physical evidence that is difficult or practically impossible to duplicate.

Knowlton makes a compelling argument that Lizzie Borden despised her stepmother enough to take an axe to her. But does evidence of any kind sufficiently support the theory? There is actually very little to give it credence—a few hostile words and petty jealousies. No witness ever heard Lizzie say that she wished Abby was dead, for example. There are no witnesses to domestic fights. Yet Knowlton makes the story credible enough. He makes sense of it. And it becomes a part of the Legend—that Lizzie Borden, driven more by ruthless venom for Abby than anything else including money, finally lost the temper of all tempers and put an end to her. But literally, this is fiction, effectively conceived and delivered by the Prosecutor.

Knowlton gives us the logistical setup of murder morning, and a reason for Lizzie’s check on Bridget at the back door. Knowlton convincingly demonstrates how Lizzie has sole opportunity to commit each murder. He attacks the note story: “No note came; no note was written; nobody brought a note; nobody was sick. Mrs. Borden had not had a note.” He asserts that Lizzie’s story about a note for Abby was a fabrication to explain Abby’s absence to her father. Knowlton then discredits the implication made by the Defense that Bridget heard about the note from Abby as well as Lizzie.

The Murder of Andrew Borden

After an adjournment, Knowlton resumes his argument on June 20th, the thirteenth day of the Trial. He states that he is not called upon to prove motive. Then he goes on to explain the murder of Andrew Borden. “It was not Lizzie Andrew Borden . . . that came down those stairs, but a murderess, transformed from all the thirty-three years of an honest life, transformed from the daughter, transformed from the ties of affection, to the most consummate criminal we have read of in all our history or works of fiction.” He describes Lizzie’s reason for killing her father as “a wicked and dreadful necessity.” Having established that Lizzie took an axe in the first place because of her hatred of Abby, Knowlton now moves on to explain why she killed her father. He has to create something plausible; what he comes up with is brilliant in that it explains both Lizzie’s sinful point of view and why the second murder was done just when it was, upon Mr. Borden’s return home. She killed her father because he would know that she had killed Abby. Knowlton implies that Lizzie had miscalculated or failed to realize something in connection with her father’s return. Knowlton’s version of Mr. Borden’s murder becomes a strangely morbid part of the Lizzie Legend—the unspeakably corrupt daughter who is driven to cover up a terrible deed by doing something even worse. Knowlton describes a chilling detail in the deed: “She suggests to him, with the spirit in which Judas kissed his Master that, as he is weary with his day’s work, it would be well for him to lie down upon the sofa and rest.” Author Victoria Lincoln would lift this and use it to great effect in her book.

A Remarkable Woman

“. . . I assert that that story is simply incredible, I assert that that story is simply absurd, I assert that that story is not within the bounds of reasonable possibilities.” Knowlton speaks at length about the implausibility of Lizzie’s barn story. He asks: Where is there a shred of evidence to support any of her various

reasons for visiting such a stifling place at this particular point in time? He explains how telling it is about the handkerchiefs—that only a few were actually ironed. As for what Lizzie said to Alice Russell the night before—Knowlton defines it in terms of cynical realism. “She goes to her friend the evening before . . . and prepared her for something dreadful.” Knowlton overlooks the fact that Lizzie’s presentiments as told to Miss Russell involved her father—not Abby—yet Knowlton has posited the theory that Lizzie did not initially intend to kill her father.

Then the Prosecutor moves into very psychologically suggestive material about Lizzie Borden the person, the human being, the woman. Does she have normal feelings—or is there indeed something of the monster in her makeup? He admits that the absence of tears under the circumstances may have been a legitimate way of dealing with horror and grief. But there are some odd things in Lizzie’s demeanor and behavior that are hard to ignore, he asserts. He points out the fact that Lizzie was not frightened out of the house, that whereas Charles Sawyer was nervous standing guard, the idea of danger never seemed to occur to Lizzie Borden. “No cry was made, no escape from the house was made, no thought of danger was suggested, but we have the calm and quiet demeanor of a woman contrasted with the agitation of a man in the same position within fifteen minutes afterwards . . .” When Knowlton refers to Lizzie’s nocturnal visit to the cellar that night after the murders, he is not speaking to the literal-minded but to those who are aware of our normal, non-rational fears—in order to suggest that something is fundamentally wrong or lacking in the nature of Lizzie Borden: “. . . she is certainly a remarkable woman. Some people may share with me in that dread of going down below the stairs into the somewhat damp and gloomy recesses of the cellar after dark. I should not want to confess myself timid, but there have been times when I did not like to do it. And all the use I propose to make of that incident is to emphasize from it the almost stoical nerve of a woman, who, when her friend, not the daughter nor the stepdaughter of these murdered people, but her friend—could not bear to go into the room where those clothes were, should have the nerve to go down there alone, alone, and calmly enter the room for some purpose that I do not [know] what connection with this case.” Knowlton’s interpretation of this is psychologically astute and scary.

How Did She Do It?

Unlike most of Knowlton’s theories, his evidence concerning Lizzie’s dress is based on eye-witness accounts. His detective work on this subject is comprehensive and completely convincing. It is doubtful it has ever been successfully refuted, although Victoria Lincoln tried to do so in her book by adding a big twist on Knowlton’s analysis. Knowlton’s conclusion is that the dress Lizzie claimed to have worn murder morning was a fraud; the one she burned was actually what she was wearing. Knowlton admits that the lack of blood evidence against Lizzie is puzzling. He attributes this largely to female cunning. But he does invent one item that has captured the imagination of writers—that Lizzie used Andrew’s coat as a shield. He points to the suspicious nature of it as it is, draped over the arm of the sofa. Perhaps the weakest portion of Knowlton’s argument concerns the hatchet. His conclusion is that maybe the handleless hatchet was the murder weapon, maybe it wasn’t; it doesn’t matter anyway, he claims. His contention is that a hidden or disposed of hatchet confirms Lizzie’s guilt, that any intruder would have left it at the scene. In an indirect sense, Knowlton is building the Legend with this particular argument, which reinforces another essential facet of it—the inscrutability of Lizzie Borden.

Where the Stream Leads

As Knowlton reaches the end, he tells the jury that there is in fact no defense from the “array of impregnable facts” that stand in condemnation against Lizzie Borden. “We get hatred, we get malice, we get falsehood about the position and disposition of the body; we get absurd and impossible alibis.” As he describes to the jury their duty, he becomes manipulative. Mercy is not appropriate now, he explains; they must have the courage to find her guilty. We are able to hear in his closing passages his awareness of the weight of the common sympathy for Lizzie Borden. “Rise, gentlemen, rise to the altitude of your duty. Act as you would be reported to act when you stand before the Great White Throne at the last day. What shall be your reward? The ineffable consciousness of duty done.”

Knowlton as Storyteller

It would appear that Knowlton realized the weakness of his case, as it was based on circumstantial evidence, and that he found it necessary to delve into Lizzie’s motivations in order to create a convincing argument for her guilt. His task was essentially to make “Lizzie Borden the axe murderess” as plausible as possible. He did this by using every shred of evidence available, in addition to his own speculations and inventions, to make her look bad, suspicious, abnormal. He did terrific analysis on the dress evidence and made a strong argument that included a clever analogy for the veracity of circumstantial evidence. But in a factual sense, he could not reach the altitude of proving her guilty beyond reasonable doubt. It is unlikely that any other lawyer could have done so. It is also hard to believe that just any lawyer could have given the same performance with the same nuances. Moody opened for the Prosecution using the same material, but Knowlton took it to another level through the application of intuitive reasoning and invention concerning the most baffling features. He told a spine-tingling story, complete with character development and uncanny details. His story has the foundational elements of the Lizzie Legend. It was told in Lizzie’s presence in a courtroom, presented whole and documented for the first time, before the verdict. What Knowlton lost in the courtroom, he actually won for posterity.