by Kat Koorey

First published in February/March, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Born into a Houseful of Adults

Emma Lenora Borden was born at 12 Ferry Street, Fall River, Massachusetts, on March 1, 1851. She was an only child in a houseful of adults, until the birth of her middle sister, Alice Esther in 1856. However, by 1860, when Emma was nine, her grandmother Phebe had died, as had her little sister. In the census of 1860, it seems poignant to notice the little nine year old’s name amongst all those of two earlier generations: Abraham, her grandfather, who was a gardener; his new wife, Barbara; her father Andrew, who was a cabinet dealer; mother Sarah; and a nineteen year old domestic named Caroline Gray.

Abraham had actually been born in 1798, the previous century. Emma’s new step-grandmother was slightly younger, born in 1801. These 18th century influences probably contributed to Emma’s development and deportment. When baby Lizzie came along in July 1860, Emma may have been starved for a new, young, fresh face and after losing her other little baby sister, she probably was especially attentive to this child. She might have resolved to raise baby Lizzie with attention, devotion and indulgence so as not to lose this one. Even before the “deathbed promise” made to Sarah to take care of little Lizzie, Emma would have been careful of Lizzie and loyal to the point of spoiling her.

Abraham had actually been born in 1798, the previous century. Emma’s new step-grandmother was slightly younger, born in 1801. These 18th century influences probably contributed to Emma’s development and deportment. When baby Lizzie came along in July 1860, Emma may have been starved for a new, young, fresh face and after losing her other little baby sister, she probably was especially attentive to this child. She might have resolved to raise baby Lizzie with attention, devotion and indulgence so as not to lose this one. Even before the “deathbed promise” made to Sarah to take care of little Lizzie, Emma would have been careful of Lizzie and loyal to the point of spoiling her.

As Lizzie grew, it is possible she took advantage of Emma’s adoration, and the special place she would hold in the house as the youngest, motherless child. A big difference between these two was that although Lizzie was too young to remember her own mamma, her much older sister was not, and at fourteen Emma was the product of already middle-aged and elderly kin, so the nine-year age gap might as well have been a generation between them. Andrew remarried in 1865, but with extended family living with or very near each other, the acquisition of a stepmother was not so apparent. The influence of the stepmother and the transition of acceptance were not really felt until the little family of four moved into their own home. At Ferry Street, there had been Uncle Hiram and Aunt Lurana in the mix as well, including their son George, who was born in 1857 and died in 1867. By the 1870 census, there is the little girl Emma, already grown at nineteen, and now Lizzie was the nine year old, replacing her. Yet Emma remained loyal, did not feel resentment toward her younger, vibrant sister, and gave to her security, commitment and devotion. The object of such loyalty would eventually rebel, pulling at those tender ribbons of affection, stretching the ties to nearly their breaking point. What a clash that would be, in the future, causing actual headlines in the newspapers around the world: “Lizzie Borden Left By Sister.” What happened to get to this point?

Away from Home for the First Time

There is very little information available on the ordinary individual’s life in those times, especially if a person lived rather normally, and was, like Emma, a shy and quiet female. A person thus described might forever remain anonymous to the world unless, like Emma, they were required to take the witness stand and swear to the details of their life. Emma did so during the inquest into the deaths of her father and stepmother and gave us her full name, her age as fourteen upon the remarriage of her father, and that she had been “away at school about a year and a half” some time ago, before womanhood.

People interested in the case have wondered about this time spent away from home and have surmised that since the family was Protestant and Congregational, Emma would probably have attended a female seminary at this crucial time in her young life, which was about the time she gained a stepmother in Abby. A popular choice then (as now) would be Mount Holyoke. Established in 1837 by Mary Lyon, in Hadley, Massachusetts, it was first named Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. There was an emphasis on the natural sciences, and educating and preparing women to teach. The early seminary of the 19th century could enroll a student after graduation from primary school, but later the requirements were stricter, accepting only high school graduates. A young woman might attend through her family’s wish that her education might be supplemented by religious study, and she might be trained for later usefulness in her community as a choir director or a Sunday school teacher.

In 1861, Holyoke extended its course of study from three years to four and in 1889 was granted “collegiate status” and the name changed to Mount Holyoke Seminary and College. In 1893, the institution was no longer considered a seminary and was renamed Mount Holyoke College. The beloved past curator of the Fall River Historical Society, Mrs. Brigham, graduated from Mount Holyoke. If Emma Borden attended there, she could have been enrolled after primary school, up until the age of sixteen at least, in the 1865- 1867 time period. It would have been considered a boarding school, and it would have been expensive. Emma stated she was away for a year and a half, which implies that she did not complete her course of study.

In 1896 there was a fire and the original Holyoke burned, and then was rebuilt. It is reasonable to assume most enrollment records were lost at that time. Wheaton was another well known 19th century Massachusetts school, established in 1835, in Norton, by Judge Laban Wheaton with a curriculum designed by Mary Lyon, which included the study of science, philosophy, literature, math, logic, history and religion. Again, this style of institution was expensive. There also existed academies for girls (boarding schools) that taught such “female arts” as embroidery and conversational French.

There is no way to know how the atmosphere of a boarding school may have affected young Emma, away from home for the first time. Did her name grant her any immunity from hazing and teasing? Did she make a friend who she kept throughout her life? Did she leave because Andrew no longer wished to bear the expense or was she ready and eager to return home? What changes to the family dynamic had occurred during that time Emma was away—how had the Borden family evolved? Did Emma treasure these memories, or did she regret the lost time away? The fact that she did not proudly name the school she attended while on the witness stand implies that it might not have been a school of great renown.

Lacking a Mother’s Guidance

During this time, in the early years of Andrew’s re-marriage, his wealth and stature was growing. Between 1860 and 1870 his personal worth had increased from $11,300 to $40,000, which combined his real estate holdings with his personal estate shown in the census. The Fall River Globe on the day of the crime would report John Morse as estimating Andrew’s worth as three times that amount around the time of his sister Sarah’s death back in 1865. Regardless, Andrew could afford to keep Emma away at school. In 1872 he purchased 92 Second Street, which at the time was numbered 66. It was a two-family tenement in the common Greek Revival style, built in 1845 by Southard Miller. Once the old owner moved out, the Borden family had the whole house, with no boarders needed to help with the costs—a seeming luxury in those days, on that street. In the early 1870s, Andrew bought, sold, and traded land in Swansea with various people and members of the Gardner family: Nathan and Charles, and their brother Slade’s widow Hannah. These deals probably resulted in the acquisition of the farms and the little duplex farmhouse, which Andrew owned with his business partner William Almy.

The Cape Cod style cottage at 1205 Gardner’s Neck Road in Swansea was probably built around 1790 and was the first home of newlyweds Joseph Gardner and Hannah Slade. When William Almy and Andrew Borden parted ways, Almy built his own summer residence at 1219, on adjacent property. In The Spectator of 1965, Mrs. Waring states that the Borden farmhouse remained unused after 1892, until 1906, except for one sitting room, which was kept nice for when Lizzie visited. The place passed back into Gardner hands, including many pieces of Borden furnishings that had been stored above the barn. Mr. and Mrs. French leased the house from 1906 until 1936. When Harold Hudner bought it from Frank Gardner he had just returned from the service and his wife was expecting. They subsequently had three more children, and seven grandchildren. They made the farm their own by planting two elm trees, one on each side of the house, but they were brought down in a hurricane. In The Spectator of 1991, Mr. Hudner reminisced: “When we moved here, there was no town water, there were no assessor’s plans and residents were afraid of zoning…there were no other houses nearby and I could wave to my neighbor who lived at the railroad station.” He replaced the two elm trees in front of his home, which he had now owned for far longer than the Borden’s ever did.

By 1872, Emma had her own large bedroom in town in a single-family home, a summer retreat in Swansea, an important last name, and Borden wealth finally to back it up. Things were improving, Lizzie was in high school and Emma turned twenty-one. There was still a chance she would make a match, even after such a slow start—but in her extended family history brides her age could easily become second wives, and hated stepmothers. Emma had a horror of that and it kept her home, quenching any spirit of adventure she may still have, although Lizzie teased her that a suitor would not just come knocking on her door; rather, she advised Emma to go out and look for her Prince Charming before Andrew married her off. But Emma was shy and lacked a mother’s guidance in such matters.

Emma’s Lizzie

Emma’s shyness grew into an inability to show her true self or to share her innermost thoughts with anyone. This compromised any real intimacy with another human being. By habit, she was protecting her essence from any outside exploration. Eventually she would suffer from this sense of isolation. She had kept herself hidden for too long, and young womanhood’s promise withered into middle-aged stolid disapproval. She had been too narrowly focused on her livelier sister, and had sacrificed her own growth and expansion. But she was pleased with what she felt she had created, with no help from a disinterested Mrs. Borden. Her project had been Lizzie and Lizzie was her creature. Emma was content that Lizzie garnered the attention, that she upset the household in flamboyant ways, and that she gained the status of a trip to Europe. Lizzie had kept Mrs. Borden always in her place, and Emma, at age thirty-nine, with nothing more in her future to hope for, rewarded Lizzie with the only thing she had left to give, her own large bedroom. At the giving of this, Emma effaced herself and committed to being part of the background, but also relinquished any responsibility for her own or her sister’s future.

Her creature was full-formed and had for several years now become independent of their boring home life, with wild expressions of her own personality inflicted on the inner family, and a softer side shown to the outside world—to friends and neighbors and board members, and those whom Lizzie wished to impress. Emma stayed at home, a product of her time and a prisoner of her own nature. Lizzie was of a more modern age, who bridled under their father’s domination and who wanted to, in Alice Russell’s words, “go and do and have.” Now Lizzie blazed the trail, and Emma would follow after. Emma would still be behind the scenes, but she would make the important decisions as a parent would for her child. It was enough.

But one thing rankled, one thing she had no control over—Mrs. Borden. It had been remarked that Mrs. Borden was “one of the kind that never die.” Her presence was becoming a torture to Emma. Lizzie could leave, serve her community, be seen at church, gurgle with glee when neighbors gossiped about her innocent relationship with Dr. Bowen, be out in the world. Emma’s world had shrunk to a very few friends, no such interest in charitable work, and she remained mostly at home. She often thought in the same prophetic and tragic terms as Henry II who had passed his tolerance level with Thomas Becket, when he lamented, “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?” Like Henry, those heartfelt wishes would become reality, and though a political empire might not fall, the results in Fall River would reach the outside world and cause a sensation almost as wide.

Satisfied with Her Station in Life

Emma had kept herself tightly controlled until now, as she had been taught—as tight as her corset, which was her constant reminder. But now, at age forty-one, she had feelings of anxiousness and paranoia, and discomfort with heat flashes, which would overpower her. She had no mother to explain the phenomena, and no sympathetic ear to guide her. She did not recognize in herself the extreme mood swings Abby herself had exhibited at least ten years previously. On her calls to her Aunt Lurana Harrington, it never seemed polite to question her on these female matters, as Lurana had been ill for so long. Even had not Uncle Hiram admonished the girls not to upset their aunt, Emma still would be hesitant to broach the subject of her body’s changes. Of the changes in her mental attitude, she had no clue. Emma maintained a higher degree of control than Abby ever did, and so Emma missed the connection. Without realizing, Emma had more in common with Abby than she ever did or could with Lizzie. Emma had allied herself with the wrong person long ago, out of a reaction to pain, out of loyalty to blood, and from an innate sense of snobbery, and it was too late now.

Emma had kept herself tightly controlled until now, as she had been taught—as tight as her corset, which was her constant reminder. But now, at age forty-one, she had feelings of anxiousness and paranoia, and discomfort with heat flashes, which would overpower her. She had no mother to explain the phenomena, and no sympathetic ear to guide her. She did not recognize in herself the extreme mood swings Abby herself had exhibited at least ten years previously. On her calls to her Aunt Lurana Harrington, it never seemed polite to question her on these female matters, as Lurana had been ill for so long. Even had not Uncle Hiram admonished the girls not to upset their aunt, Emma still would be hesitant to broach the subject of her body’s changes. Of the changes in her mental attitude, she had no clue. Emma maintained a higher degree of control than Abby ever did, and so Emma missed the connection. Without realizing, Emma had more in common with Abby than she ever did or could with Lizzie. Emma had allied herself with the wrong person long ago, out of a reaction to pain, out of loyalty to blood, and from an innate sense of snobbery, and it was too late now.

Emma would, in future, constantly be compared with her infamous sister Lizzie. It was too much to read the know-nothing ramblings of an uninformed press. They knew little of her inner nature. She was described as short, and dark-complected, and looking as opposite to Lizzie as possible for sisters to look out of the same parents. Lizzie had a light complexion with a masculine form, and was described as robust. Emma was considered listless, with a lack of facial expression—how else should she look in public—and the press decided that she was easily led and influenced by a stronger character in Lizzie.

Because Emma was satisfied with her station in life, she was reconciled with living a somewhat isolated existence. Unlike Lizzie, she was not a regular or committed church attendee, was not interested in outside amusements, and preferred to dress plainly. Let the silly newsmen report that she was not worth scrutiny within the framework of the crime, and had no part in the tragedy. She would continue in the background, plodding forward, solemn, and single-minded in her dedication to supporting and aiding Lizzie in this time of trial.

Lizzie’s Only Family and Staunchest Friend

Emma had almost as much access to her sister in jail at Taunton as Mr. Jennings. But having her visits restricted to two days a week was really to her own benefit, as Lizzie was even more irritating and demanding in jail. Emma refused to feel guilty that she herself had some time off from ministering to her sister now in the long wait for trial. Emma was laboring under the suspicion that her sister somewhat enjoyed the limelight, having all attention focused on her as her due. But at what cost? Lizzie was not considering the future. She never had. She believed she would be exonerated, her status restored and she would take her inheritance and move up into society on the Hill. Emma knew and understood that an accused murderess would never be received into gentle folks homes. She alone would be Lizzie’s only family and staunchest friend. Emma would direct their lives in circumspect ways and they could live quietly in seclusion, as she herself preferred. Neither of them realized the press now owned them, that they were in every home in the nation, their visages published so often that strangers thought they knew them. It would be nearly impossible to even live quietly, let alone with any degree of anonymity.

For now, Emma would bring Lizzie candy from the confectionary and clean clothing and religious pamphlets. Lizzie could rest just as easy and lazily as if she were at home on her own lounge. Her meals would be catered, and her quarters decorated with bouquets. There was ample mail, which always pleased her sister, and the affectionate attentions of the matron who indulged her. It was freakish and ironic that Lizzie had been accused and incarcerated under the tender care and supervision of Mrs. Wright, as she had been the dear friend of the murdered Mrs. Borden. Count on Lizzie to land on her feet in such a congenial situation and given special privileges, especially when she was ill.

Emma herself was almost worn out, disappearing under the weight of the responsibility of keeping things in order on the outside at home, and proceeding day by day, moment to moment, with the mask of respectability growing harder to promote. She was weary, depressed, losing weight and looking older, while Lizzie was gaining weight in jail! At least Lizzie noticed and commented upon it—saying she was worried about Emma’s health holding up—when she spoke to the journalist Mary Livermore. But sometimes Emma felt that Lizzie was sucking her very life’s blood, getting larger as she herself felt she was shrinking. Uncle Morse would be returning soon and would take over some of the load, and meet some of the demands of strangers, reporters, and of Lizzie too. Always Lizzie.

The mail had been the worst, with the news accounts close behind. Some of the mail had been censorious and critical, some sympathetic, but it came into her home, invading her space, unlike a newspaper. When would this onslaught to her privacy end? When could she and Lizzie retire and recharge their constitutions? She had been obsessive and tightly controlled, but was ready to snap. It had been a blessing when the rule was imposed that restricted her visits to Taunton to two days a week. It was somewhat peaceful at home now, with Uncle Morse gone, if you did not count the crowds who could gather at a moment’s notice outside.

When the Terrible Thing Happened

Emma’s last vacation was at the time of the tragedy. She had been pleasantly sojourning about Fairhaven with friends, enjoying the salt air. She had made a two-week visit at 19 Green Street before she was called home prematurely. Her friend, Helen Brownell, and her mother Rebecca, were living with Rebecca’s brother Moses Delano, with another brother Joshua next door. It was tragic that her husband Capt. Allen had died in 1884, and all their sons were dead by 1891, so there was no male support or guidance anymore and the two lone women had to fall back upon Moses. They had counted on the stipend Emma offered to keep her over the summer. The telegram that came that fateful day would interrupt her idyll and she would never be so free and unknown again.

The ghosts of those lost days would sweetly haunt her always. The next time she stayed with Helen she was invited out of friendship and compassion, given a haven and refuge over the Friday and Saturday after her trying ordeal, giving testimony on the stand at Lizzie’s trial. By then, the place Helen lived was at 66 Union Street. They enjoyed a quiet, reflective Saturday, and Emma returned to Second Street.

When the terrible thing happened and she was called home, she found there Alice Russell and Mrs. Holmes ministering to Lizzie who was keeping to her room. Without asking any other questions, other than if Bridget would like to stay, or if she saw a boy bringing a note, Emma quietly took control of the chaos, sending for some tea and toast from Mrs. Dr. Bowen for Lizzie, to settle her, and began to plan. She sent for Mr. Jennings and by Friday they entered probate, and she had approved a notice to be placed in the paper offering a large reward for the capture of the murderer. Whether or not she and Lizzie would ever have to pay that out, Emma did not know. She really did not care. It was explained that it might take some pressure off the scrutiny of the family and would show the citizens that she believed in her sister’s innocence, and had no confidence in the police. That was all that mattered. It would be well worth that reward to have this thing quickly over and done with. These splashy headlines were as intrusive and annoying as Abby’s presence ever was.

Thursday night passed with Lizzie very fitful and it was a nursing duty Emma was called to perform—something she was not especially good at. She was experienced in humoring her sister and being agreeable, but not when the chore involved holding her aching head and listening to her mutterings. Emma herself was shocked and tired, but Lizzie never thought of that.

Friday she had risen and for the first time Emma realized the absolute change in their lifestyle and habits and household routines. There was no residue of breakfast; there was not morning activity unless she herself ordered it. And yet there were guests, Morse and Miss Russell, and so she began the direction of running the household. It was at the same time sad and bittersweet, but also it seemed liberating. But she wished for the day when everyone would leave them alone. How could she realize the events that would ensue all that day—the pestering of reporters, the onslaughts on the front door, the bell seemingly incessant, until the police provided a man to stand there and take names of those who claimed a legitimate reason for wishing admittance? Emma was passed the names of callers and either approved or disallowed them, and of those whom she approved, she had to welcome. Not Lizzie.

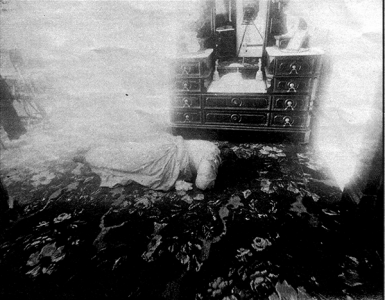

The bodies were lying in the dining room and rolled up towels were under the doors to seal in the stench and the reality of the thing. Lizzie kept to her room, Alice was there to ease some of the burden, and the only bright spot in those two horrible days were the visits of Rev. Buck, who offered to make the funeral arrangements. His dear sweet face and his sympathetic mien were balm to her soul. He truly was an angel and more helpful and kind than her own Uncle Morse. If Emma could love a man, it would be he, Reverend Buck. In those quiet, consoling moments spent with him she could let down her guard and show the grief and worry which had knotted up her insides. He had patted her hand and suggested that she rest and let Miss Russell take over the front door duty of tending to callers, which Alice agreed to. Emma’s eyes shined at the memory of the man, but she hid those feelings, as was her habit.

All that evening Lizzie acted up, was at times agitated and pacing, at others solemn and sulky. Emma had to send for Dr. Bowen several times until finally he would no longer come that night. Attending to Lizzie was the single most taxing chore she could ever have imagined. Emma had to keep herself tightly reined so as not to appear frustrated or annoyed with Lizzie’s demanding behavior, which might be construed as lack of support for her sister, and fodder to any rumors that she might suspect her sister. The fact that Dr. Bowen would no longer come that night reinforced Emma’s thought that Lizzie was not as bad off as she seemed and Emma calmed with this verification of her own intuition.

Saturday was gotten through somehow: the blood to be cleaned off the parlor door—blood to be cleaned in anticipation of company. There was the service in the sitting room, the guests to be acknowledged, the funeral cortege to the cemetery and the staring faces of the populous to be endured. Lizzie actually made a better impression than Emma herself, and of course they were compared. Lizzie was described in the papers on Sunday as attractive and well bred and obviously from a good family. They harped on Emma’s age, that she was certainly not as “attractive” as her sister, being smaller, slighter, with dark brown hair with more irregular facial features, including a receding chin.

Lizzie Suspected

Emma’s reputation was one of quiet timidity, having a manner that was inoffensive, good-natured, and diffident. Emma showed her feelings more lately, although the struggle was great to keep much of it hidden. What was witnessed and commented upon was but a tip of the iceberg. Yet Lizzie was considered composed under the circumstances, self-possessed and confident, almost haughty. Oh, how did Lizzie do it? Emma wished she had been described thusly! Well, Lizzie had been lazing away the days, sometimes stuporous, but at least well rested, and well attended. Emma, meanwhile, was worn to a frazzle and so her facial expressions gave the mobs fleeting glimpses of her inner turmoil. Lizzie liked the limelight and probably was acting—starring in her own fantasy role of poor orphan recently bereaved, carrying an air of a romantic heroine who was unjustly thrown into the spotlight and who someday would be vindicated.

This attitude never played so well as the time in the late afternoon Saturday when she and Emma received the mayor and he made the claim that Lizzie was suspected. She had risen from her seat gracefully, unconcerned, like a queen, and proclaimed she was ready to go to jail just as if she were a martyr in days of old. Well, if Lizzie could sustain the fantasy, Emma was loath to burst the bubble and so she condoned the eerie behavior as it suited her to do so. Over the many months to come Lizzie would gain a reputation for this kind of affect and she was good about being consistent with this public face. Emma admired that for a long time—but not after ten years.

There were more intrusions into their home by the police, more searches, and guards around outside at night and Emma struggled to bear it all. She felt like the only adult in the remaining family and was always relieved when Mr. Jennings was around on the premises, taking a man’s control of the situation and giving helpful advice. She knew that in some time far away in the future, she would reward him for his loyalty if she could. Uncle Morse was a bit too eccentric to be really useful, coming and going as if there were no crowds outside, engendering rumors with his odd habits—especially when he demanded the soiled and foul linens be buried and then wrangled over the price. Emma watched out of the window as he struck a deal, and the deed was done but when it was time to pay for the laborer an argument ensued. It was gauche and undignified. Only later did she find out the exorbitant price—five whole dollars! Already, someone was trying to make some money off their family tragedy—by golly—how long would that go on?

In a Home Now Empty of her Father’s Presence

The ordeal of the inquest seemed unceasing, and neither Lizzie nor Emma could recall what day it was. Emma accompanied Lizzie to the court at the jail on Granite Street and waited outside the locked room until her questioning was ended and she would be released and they would return home. Emma was very nervous throughout these examinations of her sister, and Lizzie never really told her what went on in the questioning. Somehow Lizzie must have felt she would spare Emma this recounting, but it only frustrated Emma to not be in Lizzie’s confidence at a time like this. She felt it was unwise. By the time she herself was questioned, Emma felt almost too ill to appear. They took note of her strain, knew she had not been in town that fateful day, treated her gently and released her.

When Lizzie was finally arrested, it was like a shock, and yet a release. Mr. Jennings was gracious and very sensitive as to how he broke the news, and Lizzie lay like a sphinx on the couch in the matron’s room with her eyes closed, seemingly emotionless, but her body relaxed as if it had been clenched, and now would submit to the inevitable—like someone giving up the ghost. Emma herself could no longer stand the sense of drama and burst into tears. She had five minutes alone with her sister. Emma kissed her and held her and promised her things—anything to lend comfort to these new stark surroundings. She would visit, she would bring any clothing and articles Lizzie needed, and any delicacies her impulses may require. She would staunchly support Lizzie in thought, word and deed, and keep the house running in Lizzie’s absence, until such time as her liberation. Then it was time to leave. The sense of release came to Emma during the ride home in the carriage with the blinds down. She was in utter sorrow, but also in utter relief.

She would return to their home alone but she felt Lizzie would have good care. She had a feeling Lizzie would demand it! But as for Emma herself—a chapter was ending and another beginning and she recognized a threshold. She now had the luxury of time alone to mourn her father in her own way and in private, in a home now empty of her father’s presence, no Abby around to annoy her, but both gone to the crypt and her sister imprisoned. Bridget was gone, Alice was gone, and she would from now on walk the haunted halls of 92 Second Street and relive the ghostly memories and pray that her own dear mother would watch over her and Lizzie and keep them safe from harm.

Emma did not notice the crowd’s sympathy this day for her grief at returning home alone—although finally someone seemed to have noticed her great strain and recognized her ordeal. She had one last chore to do this day—gather what belongings and clothing Lizzie would need during her incarceration and hand them over to Mr. Jennings, as if Lizzie were away on a visit somewhere. Her teardrops left marks that would soon disappear on the clothes she packed for Lizzie Borden.

Lovely Rev. Buck made a call, intruding upon her self-conscious reverie and it seemed only he knew of the heavy blow she felt this day, as heavy as was the blow of the first news of Thursday a week ago.

On Friday, Emma, Rev. Buck, Morse, and Mr. Jennings where there, present with Lizzie for her arraignment. Emma was allowed a visit with Lizzie and tried to seem cheerful and smiling, hugging her and giving her a kiss. She receded as Rev. Buck took Lizzie’s listless hand and gave her solace. After the court appearance Emma had a second chance to see Lizzie again before leaving, for only a few minutes. It was already odd and foreign to her to have someone else dictate how long she may stay to visit with her own sister. But Emma bore it well, as usual, and took it in stride, learning instantly the hard lesson that the state and laws now controlled Lizzie, her future and her fate, and Emma could not fight that battle now.

The Airing of Family Matters in the Newspapers

It was not long before another family problem arose. Mrs. Whitehead was supposedly talking to the papers about what she expected to get out of Abby Borden’s estate, and speaking for her half sister Mrs. Fish as well. Oh, there was another one—that Sarah Whitehead, who was just like Abby: uncouth, ill bred. Imagine, purposely approaching the papers to air the family business! It was insupportable, impolite, and unkind. Emma was shocked all over again—another assault on her sensibilities. Of course Bertie would make such proclamations in public. Otherwise she had not a leg to stand upon, other than to be buttressed by public opinion. Emma’s reaction was to give her the minimum of what she wanted, cut those losses, and run from that family connection.

She conferred with Lizzie but it only made Lizzie mad, and stubborn. The Whitehead woman made claim to Abby’s full estate, whatever that was. Andrew had given Abby almost everything she had, so why should a half sister benefit? Here was Bertie in the paper stating that it was Abby’s intention to see her through, and that Abby was worth up to $60,000—in part a legacy from their own father Oliver Gray, in part bank shares and mill stocks that Andrew had gifted her, and that dratted house on Fourth Street. Little did the woman realize that with no will, upon her death Abby was not going to be passing on anything to anyone, that there was no such amount of cash in Andrew Borden’s safe—no matter who anyone claimed it belonged to—and that only upon the Borden girl’s good graces, proper upbringing and genteel views of fairness would that side of the family receive anything from the Borden house or coffers. It was at their whim alone to distribute to them anything at all, and wrangling in the papers was a misguided way of instating their claim! Why, that woman even criticized the burial arrangements! Emma was adminstratrix and would decide what that woman deserved, and Lizzie would have to agree. It would be something—a trifle—the share of the Fourth Street house, Abby’s personal possessions.

There was also a suggestion that Bertie had her own personal belongings also stored at Second Street and hinted that she feared she would not even get those things back. Could she prove what was hers was the real question. Had she an inventory? Emma was quickly gaining knowledge of the law under the tutelage of Mr. Jennings and Mr. Cook. It was not something Emma had projected as an outcome of the tragedy, but she could reason well and she could learn and she could be stubborn in forgiving such an airing of family matters in the newspapers. The phrase rankled, and echoed in Emma’s head—the complaint made by Bertie in the Boston Globe on Lizzie’s first full day in jail at Taunton—“They never liked me.” Well, now anyone could see why!

Sleepless Nights

Saturday, Emma visited Lizzie at Taunton and brought her fruit and little delicacies. At home there were left only John Morse and the new housekeeper, Mrs. Barker. On Sunday, they finally skipped church, and of course, everyone noticed. But with the Reverends Buck and Jubb’s visits of sympathy to Emma and to Lizzie, Emma felt less like she was deserting her faith, and more like she was resting, gathering her strength. She and Morse had been discussing whether they should move temporarily, but he could not seem to find a place that was suitable. When he did, it was taken. They decided the expense was not warranted since they had a house already and so they stayed. They not only stayed, they stayed in. They had few callers now and lights were out by nine PM.

The nights were long and Emma had sleep disturbances—another manifestation of her aging that she did not recognize. She thought she had too much on her mind, which of course she did, as Lizzie was coming back to Fall River on the eve of the hearing which was to take place on the 22nd. Once Lizzie was housed locally again, Emma was sure the intense excitement of the town would escalate again to fever pitch, plus she herself would be making daily calls upon Lizzie at the jail. It would be easier and cheaper to visit Granite Street downtown than to take the train to Taunton as often had she had done before. She was resolved to make Lizzie’s stay cheerful, with light banter, the gift of her presence and tokens of her affection to prove her sincere sympathy with Lizzie’s plight. Emma visited every day and sent food from the Borden kitchen and Lizzie’s favorite books. The hearing was postponed until the 25th, which gave Lizzie more time to giggle and gossip and see her friends and Emma hoped to treat the reason she was there light-heartedly. Little did Emma know of the trap about to be sprung upon her unawares, dashing all her efforts to make Lizzie’s stay a pleasing one—it would not be a reaction from Lizzie that she could have foreseen.

Lizzie Turns

Mr. Jennings had been to see her, and Emma had a chance to spend a length of time in council with him, discussing Lizzie’s defense and her chances of freedom after this hearing. They spoke long and candidly and her respect for the attorney strengthened. It always felt good to place her problems in an interested man’s hands and to take his advice. Then he had gone to see his client. Emma presented herself at the jail as usual on the 24th with a smile and a cheery word of greeting on her lips and walked straight into a trap. Lizzie, without greeting, turned embittered eyes on her and accused her with a barely controlled voice of “giving her away” to Mr. Jennings. Emma was flummoxed. She was aghast and was stopped in her tracks. So all was for naught. Her own sister, whom she had tenderly nurtured to the best of her ability throughout this whole terribly unpleasant time of detainment, had got it into her head that she, Emma, of all people, had turned against her. She knew Lizzie could “turn,” but never on her.

Emma quickly blurted out, still uncomprehending, that she had only spoken candidly with Mr. Jennings and answered his questions, which he had assured her was standard procedure, and would be helpful in Lizzie’s defense. Lizzie lashed out at that. No explanation would appease her. She reiterated her accusation, turned her back on Emma, and Emma was cut through the heart. It was pitiful. Lizzie had rejected her. Lizzie had cast her off, through some misunderstanding. Emma burst into tears, the strain finally breaking her. She sat and sobbed and felt sorry for herself, a very rare indulgence these days, until it was time to leave. She hurried home and gathered Lizzie’s “troops” and sent them down to the jail to manipulate a truce. Emma knew it looked very bad to outsiders that they might now be quarreling and divided. Even though her own heart hurt, she had to be seen showing support for Lizzie. Understanding the severity of the crisis, Mr. Jubb quickly went to the jail to make a visit upon Lizzie, as did Missionary Buck, and Mrs. Brigham and Uncle John Morse. Lizzie never had so much attention in one day as that day she threw that tantrum. Emma knew it was a dangerous precedent. Rewarding Lizzie for such behavior was not something Emma wanted, but Lizzie must be appeased. And by day’s end Morse returned to the jail bringing Lizzie a home-cooked supper from the kitchen of Emma Borden.

It was supposed that such an outburst from the stoic Lizzie would presage a physical collapse and a mental breakdown. It was thought significant that Lizzie had lost her famous self-control. It was also pointed out that Lizzie must not have quarreled with her sister who was her most ardent supporter, if there was not some breach of confidence between the girls, which Lizzie made out to be akin to a betrayal. Now Emma was the one who lost favor and seemed suspicious in the public’s eyes. Oh, it was unfair, and Emma didn’t know if a breach such as this would ever be fully healed. They each could be stubborn and unyielding, but up until now, never against each other—they were always in accord. Lizzie’s weeks away in jail were bound to affect her and change her, Emma finally realized. She now had to admit that to herself. Nothing would ever be the same again now that Lizzie was away from Emma’s influence and others now held that place of advice and control. Emma would just have to accept this. But she was deeply wounded and resolved never to show it. It was as if Lizzie had grown up while Emma was away.

Each Day a Torture

At the beginning of the preliminary hearing, Emma was back by Lizzie’s side but Lizzie barely spoke to her. Emma felt reassured by the presence of Rev. Buck and Mr. and Mrs. Holmes, although Mr. Holmes seemed quiet and nervous. Mrs. George Brigham, Lizzie’s good friend, was also there to show support. Jennings chose that day to release to the press a copy of the odd letter Emma had received from this peddler Robinsky, which she had received on the 19th. She hadn’t understood any of it or what importance it might have but she was told its release was merely to promote tips from the public as to the man’s whereabouts. It never came to fruition—another dead end. Meanwhile, the story of the “quarrel” had made big news and everyone was discussing it. There were high profile names working to suppress it, or at least prove it false, which only added fuel to the fire. But Emma had already put that behind her—she had to—she could only move forward, and forward meant sitting in court attentively listening to what Bridget had to say in response to questions about the intimate life within their household. Emma was anxious, pale and concerned, leaning towards the witness, listening intently. Lizzie was also intent, but her expression was impassive. Emma whispered back and forth with Mr. Jennings and of course the newsmen noticed and commented.

On the day Eli Bence testified, backed up by two of his cronies, Lizzie was so affected the court-watchers noticed, and Emma, full of revulsion for the whole unfortunate situation blinked back the tears which threatened to overwhelm her. She could not fathom how these men could say these terrible things under oath. They were not gentlemen. They made her very afraid.

On the day of the judge’s decision, when lawyer Jennings was to sum up their side, Emma could not bear to be in attendance. She was burdened beyond endurance and awaited his verdict outside the courtroom. Coincidentally, so had Mr. and Mrs. Holmes been absent, and Lizzie had only Rev. Buck to lean on this day. Of course this happened to be the day the proceeding closed and Lizzie was adjudged “probably guilty.” Emma felt like she was in mourning now for her sister. She didn’t know how Lizzie could stand such an accusation. It was inhuman to taint her sister with such suspicion for the rest of their lives, no matter now what a grand jury or trial would find. Their name might as well no longer be Borden as they had brought shame upon the name that would never be forgotten.

The worst was yet to come. Each day was a torture and yet each day brought more. Emma had been named administratrix of the estate of Andrew Borden. She had been lulled into a short period of complacency, thinking about administering to her father’s fortune—now hers and Lizzie’s—-but hiding in the shadows, ready to pounce was the next awful scandal of the Trickey-McHenry affair. An unverified story of melodramatic proportions was printed in the Globe with outrageous claims that Andrew had accused Lizzie of gross impropriety with a man, that they had fought, and this had resulted in the killings. There supposedly were witnesses who could back up these accusations. It was obscene, and when the phony story broke, Emma had never seen Uncle Morse so angry. He was usually stoic and taciturn but this brought out his fire and he was ready to bring libel suit. Emma and Morse had to submit to questions on the matter by Mr. Jennings, in order to refute the scandalous story.

The paper was forced to print a retraction, and Emma, Rev. Buck, and Mr. Holmes flew to Lizzie’s side to assure her of their devotion. Things were quiet through the rest of October, and some of November, and Emma made short jaunts around the area looking at their properties, until she was called to the grand jury. She tried to answer their questions as best she could but she felt the invasion of privacy keenly and unwittingly presented them with an impression of haughty indignation. It was partly due to her nature of shyness and self-containment, but also because she felt that this jury had not the credentials to judge her sister or their family relationships. She had no idea she had left them feeling that her reserved manner implied that she was shielding someone and had not been candid with them. Goodness, she was merely acting like a lady should when asked irrelevant and impertinent questions. She agonized over this later, feeling she had not put on a good showing, and had let her sister down. She was not used to this kind of treatment—she was Miss Borden! She had not been trained in how to talk to the common citizens of the town in a grouping of men.

She also was not used to second-guessing herself and when the indictment came the sky came crashing down, and Emma completely lost her nerve which had here-to-fore sustained her, and became ill and prostrated at home in her bed. She had one chance to see Lizzie before the indictment, and then she collapsed. It was pathetic to see a strong person shrink like that. Then Uncle Morse decided he had been away from his business interests for too long and left to go west, leaving the girls alone over Christmas. She would never really understand that man—or any man, for that matter.

Emma gathered her strength and gave Lizzie a cheerful face over Christmas and lots of little gifts trickled into the jail much to Lizzie’s delight. Lizzie also enjoyed the mail and seemed content with her time reading, sewing, and taking walks in the corridor. The few remaining loyal friends visited Lizzie and Emma felt she could take some time to renew herself considering that the ordeal of a trial was still looming in the early summer. She felt more rested, less nervous and had better control of her countenance while she was out and about town involved with her solitary errands. Her appearance improved and she felt somewhat content, living simply, even though now she was quite the heiress.

In May, Lizzie was taken to New Bedford from Taunton to be arraigned, and on the journey caught sick. It was her first time out in several months and the result was that she was practically flattened with illness, but the doctor attended her, and although her voice was afflicted, she seemed to make a good recovery. Emma was there to greet journalist and suffragette Mary Livermore at the jail, because Lizzie’s strength was not to be taxed for too long. The result of that meeting was that Mrs. Livermore’s published story described Emma thusly:

Miss Emma Borden was a revelation: a small brown-eyed woman of 42 or 43 perhaps, in a gray house gown that trailed in Wattteau drapery at the back, and gave a certain elegance to the slight, dignified figure; her gray hair was parted and waved at either side, and in her face there was an appealing gentleness . . .This woman instinct with all the little refinements of dress, speech and manner, I could scarcely connect with the ghastly tragedy, the rough publicity of the courtroom, the caricature of the press. This was Lizzie Borden’s sister.

Their Name Forever Ruined

The trial started without Emma, as she had been called as a witness she could not attend court until after her testimony and any cross-examination. She would often meet with Lizzie before or after session. On the day the jury came to see the premises at 92 Second Street, Emma was there at home, watching horrified as the nasty bloody sofa was returned to its place in the sitting room from police storage. That was a ghastly insult to her sensibilities, and yet another insult occurred during the trial when the police came to her front door wishing access to the cellar in order to look for some long-lost hatchet handle. Emma refused them. She was curious enough though to allow Lizzie’s counsel to check the cellar but they did not find anything.

During the phase of the defense’s case, Lizzie finally perked up and was actually cheerful. It was a relief to Emma to know that Lizzie felt safe now in the proceedings, as her friends took the stand. They would not say a negative word against her, and Lizzie would feel no censure. Emma was surprised that her own appearance should cause such excitement at the trial—so much so she heard that those with good seats would not vacate them over the dinner break so as not to lose them. She herself was described as a New England type, prim and proper and maidenly and looking very like a Borden. She appeared dignified and self-reliant, confident, and with her emotions under extreme control. Although she felt on display she answered questions with deliberation and did not glance around but kept her gazed fixed on her questioner. She was lauded for her strict deportment and soon the ordeal ended. However, Mrs. Livermore published a treatment which depicted Emma as the one who had an enmity toward Mrs. Borden, saw her as a usurper, was open and vocal about it, and had a horror of stepmothers passed to her from her own dear mother Sarah, one whose memory Emma jealously guarded. Emma, after all, never pretended any deep affection for Mrs. Borden, which was so, but they did not quarrel, and never had words.

The spotlight was on Emma again and she hated it. Yet she was torn. She felt Lizzie’s plight now so keenly that in grief she had proclaimed she wished she could save Lizzie one day of torment if she could, by taking her place, bearing her burden. She still believed that regardless of the verdict, their name and their future were forever ruined. Lizzie had a different view. She believed they would have to be accepted upon acquittal, to show fairness, and those who did not accept her she would drop as friends. It was as simple and naive as that. Yet, when the verdict was announced, Emma filled with joy and was transported by the happy cheers of the crowds. For a little while they could celebrate—at least Lizzie had her freedom.

Hopes for a Quiet, Genteel Existence

They were whisked to the Holmes residence in Fall River with the top down so Lizzie could laugh with the wind in her hair and see the sky and hear the birdsong. When they approached the town limits they closed the top up again for a more sedate entrance. There was an impromptu party and the girls spent the night. The next day, with decorum, they proceeded home without fanfare, as the crowds had dispersed who had gathered there the day before because the girls were no longer expected at a particular time. There were questions asked openly about any future plans and rumor had them traveling to Europe, tearing down the house and rebuilding, moving away altogether, or buying and settling in a better part of town. In fact, in a few short months they visited Mrs. King-Covell in Newport, their ally Mrs. Holmes’ sister, they looked at property to buy in Fall River, and visited Cook their man of business. Lizzie attended church and later visited Mrs. Wright to thank her for her ministrations over the period of Lizzie’s incarceration. The sisters bought a property at 7 French Street and moved in September 7th, handed over Abby’s small estate to her family, and wrote them out of their lives. Then Lizzie headed to Chicago to enjoy the Columbian Exposition just before it closed.

They had traded up, up to the high hills, where they could ever after bask in the sweet blazing sunsets of their dear Fall River from high above the water, where the air was clear and clean and quiet. Charles M. Allen built 7 French Street in 1889, and he was the original owner. To Lizzie and Emma it was like a brand new house. It was clapboard and shingle on a stone foundation, 39’x 48 ½’ x 35’, with two and a half stories and a four-sided pyramidal turret at an angle to the street, in a Queen Anne style. It had corbelled chimney caps, verge boards, gable-topped bay windows and oriel windows, and a large cellar. Additions made by Lizzie in 1909 were a second story bedroom in the back, 14’ x 15’, and a summer veranda, costing one thousand dollars, and a one-story carriage house costing eleven hundred dollars. The house boasted Italiante arches on the first floor doorways, cherry wood fireplaces with ceramic tile hearths, odd and interesting shaped rooms, with nooks, crannies and angles. There was a built in ice house, spacious kitchen, window seats, wonderful wainscoting, cedar closets, floors of parquet, stained glass windows, a parlor upstairs as part of a master bedroom suite, and carved mantelpieces. There were thirteen rooms, most with servant call buttons. It was a fairytale house for a Repunzel, who could never let down her hair—and quite a contrast in its opulence to a jail cell and to the plain interior of the common tenement house at 92 Second Street, which had twelve rooms including the attic rooms and which they rented out rather than tear down. Lizzie proceeded to buy up lots around the new house, seemingly never owning enough of French Street.

Even though the town expected a move—who would wish to continue to live in a murder house—they disapproved. The New York Times actually described Lizzie as flaunting the fact that she refused to wear black and depicted her as going about town as if nothing had happened and criticized her for driving her buggy at high speed along the roadways. Their earlier home of their growing-up years was condemned as lacking modern conveniences and being situated in a part of town that did not suit the tastes of the new “half-millionaires,” who felt their status demanded surroundings that were more congenial. All this had been denied them by their father’s attitude. The September 10th article added:

The money that Andrew Jackson Borden first acquired as an undertaker accumulated through years of thrift, carefulness of investment and stinting his family of the actual necessities of life, is now beginning to circulate in a manner which the old man never dreamed of . . . They [the Borden sisters] are reveling in the luxuries of bathtubs, substantial food and plenty of it, the actual comforts of home life, and delicacies to which for years they were strangers. And they are at last living in a style becoming to their means and in a manner agreeable to their tastes.

Actually, the seeds of Lizzie’s destruction might well have been planted at this time of beginning a high living—with food a special fondness and of a rich quality she was not used to after the plain fare served her in the first half of her life. Lush tastes in food can be detrimental to the health of a forty-something female. Emma’s tastes were always more simple.

Emma thought they had finally settled and yet her hopes for a quiet, genteel existence were collapsed almost from the start. They must have servants and Emma found Lizzie’s democratic attitude towards them plebeian. Lizzie was too friendly with them and it was not right. It was damaging to the servant who one day may leave to be hired elsewhere and find they no longer fit into a suitably strict household. Lizzie did not understand—she made friends of them. If they were her friends, she wouldn’t be paying them.

Then there were the legal arguments, letters to the editor, and anonymous opinions all published in the newspapers about the conduct of the trial—constantly through January 1894. The annual articles written locally, commenting on the tragedy and pushing for a resolution, were the hardest news events to bear. These were constant and consistent, horrible reminders to every citizen of Fall River that Lizzie had gone free, as she was acquitted, but putting the onus of capturing the real killer squarely on the Borden shoulders. Emma Borden’s shoulders had borne too much and she would close her eyes and wish it all away. Yes, even the money, even the house, even Lizzie. Would it never end?

In December of 1896, there was a planted story announcing Lizzie’s engagement to her cousin Orrin Augustus Gardner, son of Henry Augustus Gardner, which would never come about. He was born July 21st, 1867 making him seven years younger than Lizzie, but they were similar in nature with birthdays near each other. He was a schoolteacher in Swansea, Tiverton and eventually Fall River and later became principal of the Highland School, Fall River, and by 1912 was principal of the N. B. Borden School of Fall River. Orrin never married, and he was included in Emma Borden’s will. He obviously held her affectionate regard. His mother was Caroline Cole Mason, whose sister, Ann Frances Mason, was married to William Bradford Morse, Lizzie and Emma’s uncle and John Vinnicum Morse’s brother. Ann was their aunt and John Morse’s sister-in-law.

The Gardner’s kept a beautiful house called Riverby, out in the country in Touisset across the water from Gardner’s Neck. As Lizzie had been a friend with Orrin, so had Emma been a friend with him, his brothers Frank and William and his cousin Preston, whose father Nathan, was Henry’s brother. Orrin, Frank and their cousin Preston, all graduated from Warren R.I. high school and Bryant & Stratton Business College. William became a teacher, like Orrin, whereas Frank went into the ministry. Preston was doing well in Providence and Emma found him most refined.

To Live as the Sister of Lizzie Borden

It was humiliating to see more headlines splashed across the Fall River Daily Globe in February 1897 just two months after the false engagement announcement. This time the scandal was nearly as bad as accusations of murder—Lizzie was boldly charged with stealing two paintings from Tilden-Thurber. Preston and Mary Gardner were involved and somehow Preston fixed the situation so that Lizzie was not ever served with the threatened arrest warrant.

Then in August, Emma shuddered again to read the annual announcement that the murderous fiend had not yet been found out, and in the following year, 1898, the description degenerated into “the thing which slaughtered the Bordens.” Lizzie was indignant but reconciled, and Emma wondered if she secretly enjoyed seeing her name in the papers somewhat regularly.

In December of 1898, Aunt Lurana died at the age of 73, after suffering for many years painful attacks of neuralgia in her back and face, enduring three operations. She was the last of Andrew’s siblings and now they were all gone. Uncle Hiram was left, but since his only child with Lurana had died a lifetime ago, he never really felt like kin, especially once he and Andrew had shunned one another. At least the murder story was not revived in the death notice, and only the information that Lurana was the daughter of Abraham and Phoebe Borden and wife of Hiram Harrington was printed. It was tasteful. It was the last close blood link to their father Andrew, and now they felt very much alone. An act of merciful providence took Lurana—her life had been tortured with pain even on the day her brother was killed. Now they were together in the sweetness of heaven. It didn’t occur to Emma that any relationship to the Borden girls was deliberately left out of the notice because Hiram and his kin did not wish to be associated with the Borden murder tragedy. It didn’t occur to her that a whole town might deny her sister’s name in the future, and wish it could be swept right under a rug.

The next scandal to be endured was the absurd news announcement that Lizzie would wed a jury member of her trial, who always believed in her innocence. Of course he always believed in her innocence—he judged her not guilty! Did Lizzie pass along these rumors? Emma was suspicious, and becoming more unhappy with the decision to stay in Fall River, setting themselves up on the Hill, only to be ogled by the curious and uncouth who were making the rounds from Second Street to French, hoping to catch a glimpse of the infamous Lizzie Borden. Emma had no idea how hard it would be to live as the sister to Lizzie Borden. Emma was still considered shrinking and quiet compared to Lizzie’s self-assertiveness. Emma wanted only to find peace and solitude and she was beginning to know the truth—that she herself had not changed much but that Lizzie had metamorphosed into something she no longer recognized. They had always had their differences, but had always been congenial. Now Emma was at a loss as to what to do. The century was changing, and Lizzie was changing with it, but Emma would be left behind, in the 19th century.

Near Neighbors

By spring 1900, as Lizzie was approaching forty, she was becoming nervous with bouts of disturbed sleep. Emma recognized the symptoms now—she herself had gone through that phase and was sympathetic. But Lizzie did not wish to be tutored in the subject of aging and rebuffed Emma’s efforts to discuss it. Also, without informing Emma, Lizzie wrote to Mr. Brayton, a near neighbor, complaining about his little rooster that crowed in the early morning, disturbing her. Lizzie had never been an early riser and her resentment at being awakened was acute. She had blurted out her dissatisfaction in a note to Mr. Brayton and sent it off expecting him to comply with her wishes. Emma suspected Lizzie did it simply because she could. She was a near neighbor and was reminding him of that fact. Emma shrunk a bit more.

Another near neighbor was the Hood family around the corner on High Street. Alfred H. Hood was a senior lawyer at Lincoln & Hood law firm on Bedford Street. His father, William Perry Hood, had been a Justice in Bristol County, and had served a year with the Massachusetts State House of Representatives in 1862. The Hood family was prominent in Somerset.

Alfred’s son, Preston H. Hood, grew up on High Street, and was active, athletic and bright. He liked to play baseball and happened to hit one right into the window of Maplecroft. Of course, he was hesitant to go ask for it back. Another time, Lizzie’s little dog came over, grabbed his mitt and trotted home with it to Maplecroft, as a sort of prize. Preston went after it, calling at the house. He must have charmed the Borden ladies because he made a friend of them, got his mitt back, and they did not forget him. Later at school he would be captain of the debating team, and a very fine badminton player. Once he finished school, graduating from Brown, and then Harvard with his law degree, he entered his father’s practice specializing in estate work and Emma became his first client. It is safe to assume that his Aunt, Josephine Ridlon, also worked at the law firm, as she boarded with her sister and the Hood family at High Street and it is noted that she worked as a law office bookkeeper as recorded in the census. She would be contributing toward her room and board. Emma and Josephine (who was nine years younger and had remained single) became friends. Emma had an affinity and respect for intelligent and genteel spinsters who supported themselves. They were close enough friends for a long enough time that she was remembered in Emma’s will and codicil, bequeathing to her a total of $3,000 and all of her clothing, which was an intimate gift. That also may imply Josephine’s taste, style and size. The codicil was dated 1922, which increased the bequest.

The Hood family was definitely in favor with the Borden ladies, as also upon Preston’s marriage to Ruth Williams in 1916, they were gifted with an exquisite silver service, a chair and a hall rug. There is a bizarre family story about that silver service, but because it came from the Bordens, it is not surprising. After Ruth’s death, Preston was given a large guard dog to keep him company and safe. One evening, he was dropped off after dining out, and as he entered the house he stumbled upon a masked bandit. He rushed to get his gun but was ambushed by two more men, who taped him up and threatened to kill him and wanted into his safe. He explained that he hadn’t a safe but did have a gold coin collection worth $500, and so he was cut in the neck, his coins were taken, and they left. He raised an alarm and the police came to be greeted by a happily wagging Cleo! Preston had managed to make his guard dog sweet and friendly. The gang was caught six months later robbing a local bank. Preston always referred to them as “Gentlemen Burglars” because they had not killed Cleo and they had not stolen “Lizzie Borden’s Silver Service.”

Preston’s son, Roger Hood, and his bride of sixty years, Virginia, are no less a couple of strong-minded characters. They graciously told stories about the Hood family and it’s prominence in the Somerset area. They are political activists in their community: Roger is combating the LNG initiative and Virginia writes letters for local preservation causes with some success.

Ready to Disentangle her Life

Emma made sure to call on all her friends—Josephine Ridlon, the remaining Buck sisters, Helen Brownell and the Gardners—although they rarely called at Maplecroft. Her few friends were loyal and Emma felt grateful, but she knew part of the reason why they stayed by her was because she at least was still considered respectable. Emma understood that and made sure that her public persona and quiet demeanor would remain pleasing, even though everything was very hard to deal with at home.

Emma had an elegance of spirit with sense and sensibility. She was the exact product of her times, and because of her dignity in all situations she fit in anywhere. This was due to her own nature, but also her mamma had trained her well. But Emma bore a lot of suffering which she never showed. Decorum dictated that she be attentive to her personal appearance because of the impact that impression would make. Included with that training was the knowledge of polite social discourse, all which she knew was superficial and old-fashioned, but she was comfortable with that. She knew not to put herself forward, was taught to stay in the background, and the realization was there that she was becoming more inflexible and out-of-touch in this new century. When Lizzie developed a love of theatrics and an obsession with a famous actress that included a curiosity for the freewheeling lifestyle she seemed to lead, Emma was ready to disentangle her life from her sister, cut her losses and move on. But the decision was not an easy one and no one, least of all Lizzie, would ever understand the agony she felt in breaking her bond of commitment to her sister, and that she would always suffer from these unresolved emotional wounds. Emma had not allowed for Lizzie to change; she had tried to lock her into a static role, and Lizzie had rebelled. Emma felt she had followed Lizzie’s trail as far as it could lead her, but now Lizzie had to experience the unknown and Emma did not wish to follow.

She Would Live with Others the Rest of her Life

Emma packed and sent her things to storage, signed a financial agreement with Lizzie over the use and upkeep of the French Street property, and fled to Fairhaven in 1905. She would live with others for the rest of her life, never really belonging anywhere once she gave up her dear Fall River. Helen Brownell was willing to give her a refuge and helped her to find more long-term boarding arrangements. In the meantime, the extra stipend helped her friend, while Fall River gossiped over the breakup. Over the next twenty years, Emma would essentially be a vagabond, and Lizzie never sought her out and invited her home. Emma preferred Fall River and would return to it for a time, but she would always leave again.

Helen was head of household in 1900 at 31 Walnut Street in Fairhaven, and still single at age 61. In 1902 the address of Helen was 23 Walnut Street, and also living there was Helen B. Copeland, assistant to the Fairhaven Postmaster. The area where the house was situated is now Unitarian Memorial Church property. Emma had friends and acquaintances in the city and was relatively satisfied with her escape. She felt more comfortable around her older friends of her own generation. There was sympathy and compassion for her ordeal, but Emma was strict about putting all that history behind her and never discussed it. By August 1906, Emma was actually visiting Scotland and sent a postcard to Mrs. George Brigham from Glasgow. It had rained on the trip and she had visited Sterling Castle and she was having a wonderful time. This August she was determined to miss that dratted annual article on the murders and was a continent away and barely gave it a thought.

By 1909, Emma had moved in with cousin Preston Gardner and his wife Mary at 211 Hope Street in Providence. It was a fine house, and a fine neighborhood on the east side of Providence. It was not too far from the shopping district of Westminster Street and Mathewson, where Tilden-Thurber was located, Lizzie’s favorite area to shop. But still Emma never saw her sister, though well-meaning friends kept her somewhat apprised of her movements and actions. Preston was now head of the Trust department at the Rhode Island Hospital Trust Company of Providence, but because he had a small family, Emma felt her stipend, that paid her board, was useful to them. She liked to think she was helping those with whom she stayed.

Preston Gardner had a bright future and by 1912 he would become Vice President of the company, in 1921, a director, and in 1936, Chairman of the Board. He served as Treasurer of the Providence Society of Organized Charities, and became a trustee of the Greater Providence YMCA. In his younger days he had taught bookkeeping in the evenings at the YMCA. He had a long association with that organization, which also inspired Emma’s interest and she made provision for the Fall River YMCA in her will. His wife Mary (Hoyt) Gardner was one of the founders of the Providence Animal Rescue League and became its honorary Vice-President and Trustee. Through their passion for these charities, Emma was educated to the needs of such organizations and their benefit to the community. In August 1919, Emma established a deed of trust with Preston’s organization, endowing a fund with $700 in Third Liberty Loan Bonds to benefit the Providence Animal Rescue League, and in 1920 in her will she added $5,000 to the fund, and in a codicil to her will dated 1922, Emma further enhanced the Trust she had set up with $15,000 more upon her death. It would be seen that Emma was endowing a charitable organization in her own lifetime, and promising more in the future. This was a project dear to Mary’s heart, and the funds were to be distributed through Preston’s company. It might also have been helpful to Preston’s career for it to be known his heiress cousin was leaving money through the Trust Company.

Emma thoroughly honored and emulated this side of her family by these actions, whereas in 1912, when John V. Morse died, she had rejected his bequest to her personally. Emma would continue to ally herself with the Gardner family and made her future funeral arrangements with Preston’s Aunt Caroline in Touisset, her own Aunt’s sister.

Emma would also generously remember Preston and Mary and their daughter Maude in her will. Maude eventually married Elmer E. Dawson and they would have a son, John E. Dawson. By the time Mary died on May 22, 1945, the Gardner’s had been living at 500 Angell Street, Wayland Manor. It was an illness of several months duration, and the legacy from Emma would be very useful. Preston lived to be ninety, after spending sixty-two years with the Trust, retiring in 1947 as Chairman of the Board. He had led an exemplary life of hard work and dedication to his career and family, and died at Jane Brown Hospital on October 22, 1953. The home they had shared with Emma at 211 Hope Street became the personal residence of the Headmaster of The Wheeler School, a prestigious private day school for nursery through grade 12, located at 216 Hope Street.

Emma longed for Fall River and moved there in 1913/1914 to board with the remaining Misses Buck at 114 Prospect Street. “Father Buck” had died on March 9, 1903, his body lying in wake in the house until March 12th, whereupon a service was preformed, and then he was removed to the Central Congregational Church for an hour-long funeral and viewing, being laid to rest in Oak Grove Cemetery. Emma had missed her good friend, advisor and teacher, but so had a multitude of others, and no less his family. When Emma moved in they only had part of the house, and Elizabeth, Alice and Mary had remained. Clara, the youngest, had gone to be a teacher in Mattapoisett by 1900, boarding there. Mattapoisett, considered South Swansea, was in the Gardner’s Neck area. Mary, the third Buck child, was working in Fall River as a kindergarten teacher.

Again, Emma’s money for boarding was a help to the household and the girls were very near in age to Emma and they shared a worship of the memory of the father, Rev. Buck, and they held that love and respect in common. It was from this house that Emma conducted the famous interview with the Boston Post reporter in 1913. She had been overwrought, but cordially gave a few answers to questions about Lizzie, to show her support in fellowship and compassion for her sister, now “Lizbeth,” who was still being gossiped about in the newspapers. The reporter embellished her comments as she attempted to defend her sister, and Emma felt her sincere words were trampled and her intent skewed. She realized she had lost control of that situation, and she would not make that mistake again. It was undignified, but she put the experience behind her. She was relaxed and meditative in the quiet company of her spiritual sisters, the Misses Buck, and they would commune peacefully in the evening hours on the porch with a view of the water burning in sunset. As the purple sky became dominate over the fading oranges, pinks and reds, they would speak of the cherished memory of the late Reverend, and be soothed. One of his accomplishments had been to found the Fall River Boys Club, and Emma resolved to include that organization in her will allotting $5,000 in trust, and his daughters were truly grateful that his charity would benefit. It seemed that as she moved from place to place she became more educated in the world, found causes close to the hearts of others she admired, and was influenced by that experience to remember these charities in her will.

By 1919, Preston and Mary Gardner had moved into a new high-rise eight-story luxury apartment building at 121 Waterman Street, called The Minden. Emma had visited the Gardners there and liked it. She acquired her own apartment at The Minden. She had a companion to live with her and apartment life suited her: small, manageable, her own place but with close friends nearby. There were many apartments and many tenants and she was mostly unnoticed. Because of its modern luxury, other residents were of a higher class; well-heeled individuals who valued their privacy. She had a nice view of the city and loved the sight at night with all the electric lights flickering. Poor Lizzie now was the one seemingly stuck in a Victorian time warp, still attached to that French Street address. Emma kept her Mindon Apartment until 1926, the year before she died.

The Minden was built in 1912 by Julian Lewis Herreshoff and his brother, who were from Point Pleasant Farm, Bristol, R.I. Julian went to local schools and then in 1886 he went to college for two years at the University of Berlin, studying music and languages with an interest in fine arts. In 1977, The Minden was bought as a dormitory by Johnson & Wales College. When that changed hands, several surviving Minden residents moved to Wayland Manor in Providence, the only other luxury apartment building, as the Gardners had done prior to then. In 1999, Brown University acquired the building, but in the year 2000, with a new dormitory yet unfinished, Johnson & Wales rented back the building for housing for 145 of its students. Today, it is being renovated thoroughly for Brown students and is undergoing a major overhaul.

Emma liked to leave the city in the summer and, through Preston’s connections, a place was suggested in Newmarket, New Hampshire. Preston’s cousin Frank had been ordained in the ministry and had occupied the place as Pastor in Schultzville, N.Y., Lubec, Maine (for five years) and for ten years had been located in Portsmouth, N.H., from 1902 to 1912. Portsmouth was about fifteen miles from Newmarket, and there was found a young lady named Annie Connor who was a trained nurse and she and her sister Mary took boarders in their home at 203 South Main Street, near the center of town. Emma went to board there the summer of 1923 and by the following season, after Mary died, Emma returned to live there full time. Annie needed the money and gave board to no one else, becoming a companion to Emma as they shared the house.

Emma was feeling old and ill so a change of scene was welcome, and the town charming. Natives minded their own business. It took a long time for any news of her identity to get around, but no one accosted her. They left her alone, because, after all, the murder mystery occurred a generation ago in another state, and was not something the citizens especially remembered. Emma had almost outlived the scandalous tragedy.

In the winter when it was icy outside one simply stayed indoors. There was a helpful young man, Royce Carpenter, son of Jesse Carpenter, who lived diagonally across the street at 204 who would chop the wood and stack it in the carriage house out back and who ran errands. He was an enterprising boy who also kept a job as a silk winder at the mill. Emma spoke to him rarely, but politely called him by his name and would make small talk, asking him a general question now and then. She commented that she wondered if it was hard work to cut the wood and stack it so, as she watched him at the job. Royce was curious about her but always busy and did not get to know her, but he always remembered her.