by Kat Koorey

First published in August/September, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Andrew Borden lay dead, oozing blood and brains onto the sitting room sofa, which pooled on the carpet beneath. No one seemed to know where his second wife, Abby Borden, was, but it was thought she had gone out earlier. Officer Allen was the first policeman at the scene to check on the affray. After making sure that the front door was locked, he left civilian Charles Sawyer to act as guard at the side door. Allen rushed back to the station house, prematurely it seems, to report the horrible details of one death only.

Meanwhile, Dr. Bowen, a family friend from across the street, declared Andrew Borden murdered and rushed out to telegraph the victim’s eldest daughter, Emma, who was away on a visit in Fairhaven. It seemed important that he notify her, perhaps in the hope that she could return on an early train and take over the duty of comforting the remaining daughter, Lizzie Borden, who had been about the premises at the time of the attack.

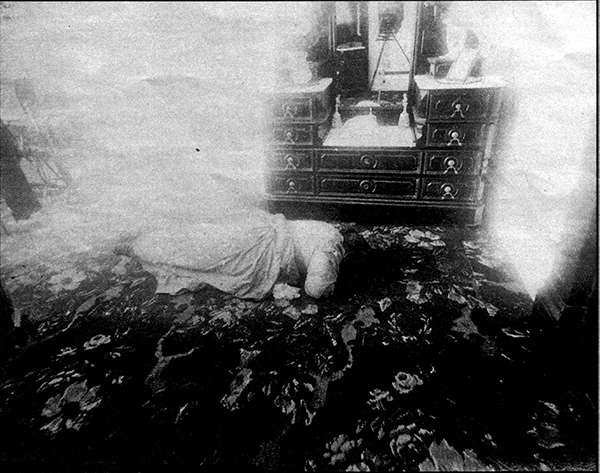

The neighbor, Mrs. Churchill, along with the Borden maid, Bridget Sullivan, crept slowly up the steep front stairs on the lookout for a criminal whilst checking the possible whereabouts of Abby Borden. Mrs. Churchill was astute, espying the motionless form on the floor on the far side of the bed in the guest room from her view on the staircase. She turned and immediately descended to break the news of another body—and not just any body, but that of her near neighbor, a harmless God-fearing, law-abiding gentlewoman like herself. Bridget continued up the staircase, somehow drawn into that room. She stood at the foot of the bed and stared frozen in disbelief at the bloody body of her mistress. Becoming aware, she shrugged off her ennui and exited the room, perhaps realizing she was alone there with a victim of who-knew-what horror. She could not guess what the cause of death was in that moment. It took Dr. Bowen’s return, and the almost simultaneous onslaught of outsiders who overran the place, before the severity of the situation sunk in. Bridget probably blessed herself and called on all the Saints to keep her safe when she realized the narrow escape she had had, alone earlier in the house with a murderer. She and Lizzie Borden had been spared from the slaughter.

By 11:45 that morning—after officer Doherty had been to view the bodies, moved the bed away from Mrs. Borden to check her wounds, gone to telephone the station, and returned—there were almost a dozen men in the house of horror, and three ladies with Lizzie, administering to her. When Doherty next entered the chamber of that gruesome murder of the elderly defenseless woman, there were now two doctors, Bowen and M.E. Dolan, and Mr. Borden’s brother-in-law, Mr. Morse. While officer Allen looked on, officer Mullaly assisted Doherty in turning Abby so her face was exposed, and they saw that her features looked all mashed in from bruises and livor mortis. As Allen left to inform the Marshal, he noticed a handkerchief “covered with blood . . . lying from Mrs. Borden’s feet toward the window,” which he recounted at the trial. He was asked if he could identify it and replied, “Yes, sir, the border is cut. (A ragged handkerchief was shown the witness.) Yes, that is the handkerchief.” Mr. Moody then told the court, “We offer this, if your Honors please.”1 Allen further described it as “wet in blood and lying in a—just as you have it now.”2

Dr. Dolan had been passing near the area of Second Street, and, as a medical examiner for Bristol County, inserted himself into the scene, taking charge. He was in the room examining the body when Allen was there. At the preliminary hearing, as the first witness called on the first day, within the first ten minutes, Dr. Dolan was asked: “Anything on her [Mrs. Borden’s] head?” Upon his memory, Dr. Dolan described a silk handkerchief “near the head,” more suitable for wearing upon the head when dusting, than as a dusting cloth. It was “not knotted…[nor] cut…torn very freely…[with] some blood on it from the surrounding blood.”3

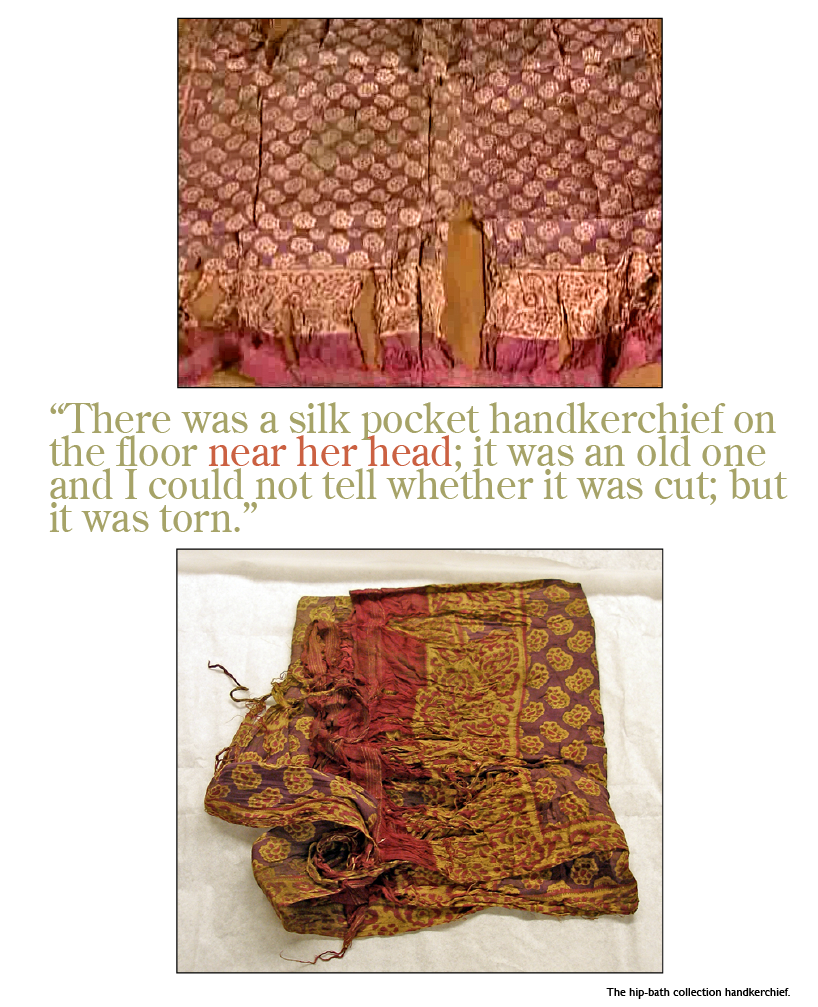

After absorbing the atmosphere of this despicable crime against these two poor old folks, very important questions arise: Why is this handkerchief at the scene of Abby’s murder? Whose is it? It was near her feet – it was near her head; it was not knotted as if worn, but not the right material for dusting. What does it mean? It seems to be the one thing out of place, inexplicable, and the authorities seemed to wonder the same thing. The next year was spent hunting clues in the case and this object was continuously brought up and asked about, its description was repeated in an attempt to place it into some context, with no definitive answers forthcoming. Regardless, this is an important artifact, found with the body of Abby Borden and “wet” in her blood. It has become an item of mystery, now lodged at the Fall River Historical Society and rarely displayed due to the fragile state of the decomposing silk.

Other handkerchiefs in the case

There are other handkerchiefs in the Borden case that appear and promptly disappear, like a magician’s prop. However, the tattered one has outlasted them all, surviving to this day. Abby Borden had traversed Second Street to pay a worried visit to Dr. Bowen just after breakfast on the day before the murders. She wanted a diagnosis of her and Andrew’s vomiting of the night before. She seemed well enough to have imbibed pork steak before her early morning consultation, but Dr. Bowen did notice her gagging and fully expected her to erupt into her own handkerchief.4 His opinion was a cursory one of a common summer illness, which was reinforced later that morning upon his visit to Andrew to check on him. Dr. Bowen found little to be concerned about owing to Mr. Borden’s attitude. Certainly, Dr. Bowen cannot be faulted for lacking pre-sentience.

The morning of the murders, Lizzie’s own personal handkerchiefs, and her ministrations over them, were the subjects of much discussion relating to her movements on the day. Lizzie could not seem to accomplish the chore of ironing all of them before that fateful chime of 11 a.m. The question put to Bridget at the preliminary hearing, and her answer, states that Lizzie only ironed her own handkerchiefs 5 It had been implied that this handkerchief found by the body was not Lizzie’s because it was man-sized, nor placed out with her ironing because she only did her own. Lizzie, as any lady of good taste at the time, would have had pretty, dainty ones, possibly embroidered or edged with lace.

Another handkerchief reference appears in the case as the useful cloth that was used to hold and secure Andrew’s keys removed from his corpse’s pockets. This handkerchief was brought to Dr. Dolan in court at the preliminary examination, and once the keys were discussed, this purveyor promptly lost its importance. It is not readily apparent to whom this handkerchief belonged.6 A Victorian man’s pocket silk square could be at least 13 inches by 13 inches and worn decoratively, or easily tied off at the edges to carry objects. It could also be worn on the head to protect from the sun, or, in the case of a housewife, to keep her hair clean whilst dusting something above her own height.

But did she wear it?

John V. Morse, the Borden girls’ uncle who stayed overnight August 3 to 4 in the soon-to-be death chamber, was one of three to testify as to when he last saw Abby Borden that Thursday morning. Morse was the first family member to be called at the trial on June 7, 1893. He claimed Mrs. Borden was using a feather duster and entered the front hall, and he thought she must have gone upstairs. He testified twice that she had nothing on her head. Prosecutor Moody asked: “Do you know whether she [Abby] had anything on her head as she was dusting?” Morse answered, “I think not.” And, once more: “To put my question again, did you notice whether she did or not have anything on her head?” Morse’s final reply on this topic in a court of law was “I think she did not.”7 The extra emphasis on this particular question by Moody seems to imply that he expected a different answer, even though Morse answered the same the year before at the preliminary hearing.8

Bridget Sullivan was asked at the same preliminary examination, on Friday, August 26, 1892, when she last saw Abby Borden alive. Bridget answered, “She had the feather duster in her hand dusting the dining room,” after Morse had left the house that Thursday morning.9

Lizzie Borden was questioned at the inquest, August 9, 1892, about her stepmother’s habits while dusting. After describing Abby as using a feather duster in the dining room on the morning of the murder, she was asked, “When she [Abby] dusted did she wear something over her head?” Lizzie replied, “Sometimes when she swept, but not when dusting.”10 The important context here was that it was accepted that Abby had done the housekeeping work in the guest room before Lizzie came down that morning (by around 9 a.m.) —Abby had already “dusted the room and left it all in order…she had done that when I came down.”11

According to John Morse, and implied by Bridget and Lizzie, when last seen, Abby had not had anything on her head, and no reason to have anything on her head. No one was asked if any handkerchief found with Abby belonged to them. No one was asked if this hankerchief was Abby’s, Andrew’s, an unknown killer’s, or left behind by a zealous spectator at the scene—until the last week of the trial, almost a year later. Doherty claims not to have seen it, but it is not clear when he did not see it—before or after the room got crowded.12 Since the carpet was dark, as was the blood and handkerchief, it is possible it escaped his attention, especially since the bed and three chairs were moved.13 By the end of the first week of the trial, the following year, newspapers tried to connect that handkerchief to Lizzie Borden.

Sometime that Thursday noonday, Charles Sawyer left his post at the side door and went to the guest room to view the body. On August 11, he was asked at the inquest, “Did you see any more bloody cloths around there?” His reply, “No, except what was around Mrs. Borden,” implies other bloody cloths, but it is not certain when he made his view.14 In the illustrative drawing published on August 6, 1892 in the Fall River Globe, there is captured within the detail of the patterned carpet a white-looking wadded cloth near Abby Borden’s waist. This is obviously not the dark-colored suspicious handkerchief, and it has never been identified.

The photographs

Newspapers of the time did not yet have the capability to reproduce a photograph and so employed their best artists to render illustrations from life, from memory, or from photographs in order to capture the public’s imagination. In the Borden case, this was done routinely and yet the crime scene photographs are still in existence, a treasure beyond price, surviving over 100 years.

James Walsh was sworn in at the trial on Wednesday, June 7, 1893, and introduced two sets of five photos. Exhibits numbered #10-14, inclusive, were of the Borden premises and photographed on the previous Saturday, June 3. The other five were taken the day the crime occurred, August 4, 1892. A photo of Mrs. Borden in the bedroom (exhibit #15) was taken at about 3:30 p.m. at the request of the M.E., and the body, the bed, and the bureau were in the position Walsh found them in at that time. The “Other view” of Mrs. Borden in the bedroom, labeled “exhibit #16,” was probably taken within minutes of the other. This photo without the bed shows a wadded whitish cloth near the body. Exhibit #17 shows Andrew Borden on the couch. Exhibits #18 and #19, variously the head of Mrs. Borden and the head of Mr. Borden, were taken the same date, but at 4:30 p.m.15 By then the heavy, stiffening body of Abby had been removed to the downstairs dining room where her partial autopsy occurred. Dead seven hours, she would have been unwieldy to move and maneuver down that steep and winding staircase, causing more indignity to be suffered upon her.

Burial and resurrection

The bodies of Mr. and Mrs. Borden were stripped, and the bloody clothes, pieces of carpet and cotton cloth, and all sorts of detritus of the crime were delivered to the cellar to be stored in the laundry room. On Friday, August 5, newspaper reports blamed a nervous John Morse for agitating to have these rotting items buried, and put out of the sight and smell of the surviving family. Albert Chase enumerates most of these items in the Witness Statements, but he claims the burial was under orders of the M.E., which it was not, and he does not add the bloody handkerchief to the list.16 In fact, his list is in no way complete. The newspapers filled in the controversial details from this point on Friday, August 5, until the end of the inquest.

On Saturday, August 6, the Providence Journal, the Boston Globe, the Fall River Herald, and the New Bedford Evening Standard all promoted variations on the story of the burying of the blood-stained clothes on Friday. Related elements had John Morse engage a man named David P. Keefe, a letter carrier, to do the job for $5. Keefe seems to have subcontracted the labor to a restaurant worker named William Niles.17 When it came time to pay, Morse argued about the price. Then, still in a fit of pique, he “locked the barn when a couple of Boston newspaper men were inside, and found considerable fault with the liberties people took with the premises. He was reminded that a reward of $5000 had been offered, and that everybody was intensely interested.”18

The Fall River Herald, on Monday, August 8, hinted that the outcome of a visit to the receiving vault at Oak Grove cemetery on Sunday, by Drs. Dolan and Leary with Assistant Marshal Fleet to reassess the bodies that had not yet been buried, would result in an order to dig up the bloody clothes. Even the man Niles was named as advised by Fleet “to be present at the house at 2:30 p.m. [on Monday].”19 And so it was done. The Boston Globe, August 9, under the headline “No Footprint,” told the story of a quiet and secretive resurrection of the artifacts from the Borden yard, where Dr. Dolan warned the duty officers that no one passing by should be able to observe or stop and gawk or gaze, nor should anyone be allowed to enter the yard, which included Morse, when he tried.

After the disinterment, Keefe and Niles watched as:

Dr. Dolan took each particle of clothing and stained effects of the deceased persons out and carefully scrutinized them.

Besides the clothing, there were certain stained clothes, which had been used to cover the bodies upon their discovery Thursday forenoon, and also the pieces of carpeting soaked with the life blood of the victims.

The doctor went over them all until he had selected such as he thought would serve his purpose.

Then he cut off a large piece of the coat and shirt worn by Mr. Borden when he was found upon the sofa, and with his scissors clipped off a piece of the waist of the dress worn by Mrs. Borden when killed, all specimens matted with the blood of the victims.

The doctor proceeded in a like manner to take part of a large piece of carpeting cut from the spare bedroom, fairly saturated with the crimson fluid.

These were eminently satisfactory to the examiner, and he ordered Keefe to procure a box for their reception.

All the rest of the clothing was again buried in the former condition.

Dolan put his items in a box and rode off in his carriage. The paper opines that this was done in order to compare any blood on the ax held by the experts with the blood on the objects exhumed, after first assessing if it were human. The Fall River Globe of the same date reported that “two lots of hair found clinging to Mrs. Borden’s clothes” were taken by Dolan and the remaining items were “placed in a shoe box and buried four feet below the surface of the ground.” Seemingly, a different edition of the same paper included the macabre anecdote that “a reporter asked to receive permission to select a part of the clothing as a memento of a mystery which he regards as the most puzzling of his long career. He smilingly told the examiner that he had choice bits to remind him” of other interesting cases. Since this project was carried out in secrecy, but blazoned in the Boston Globe, the Fall River Evening News and the Fall River Daily Globe, how secure was the secret, after all?

By August 11, the last day of the inquest and the occasion of Lizzie Borden’s arrest for murder, the remaining items that would later be introduced as evidence against her in the case were wholly and finally exhumed and retained by the prosecution. These actions coincided with the more complete autopsy of the Borden bodies that Dr. Dolan performed that Thursday. The headless corpses were eventually taken from the holding tomb and interred in the family plot in Oak Grove cemetery on Wednesday, August 17, 1892, at 8 a.m., thirteen days after their murder.20

In evaluating Dr. Dolan’s trial testimony, it seems that it was a serendipitous recovery of the “old silk handkerchief…shredded from wear” that had been “buried with the rest of the clothing.” Knowlton had the witness confirm it was “dark colored” and had blood on it. Upon being shown the relic, Dr. Dolan concurred that it was the handkerchief, and that, in its “entirety,” it was still in the same condition. It had not been deemed worthy of keeping out of the re-burial, but survived in the lot of other items—those “finally taken and carried up to the Marshal’s office,” whereupon Dolan then received it from him, and was in his “custody” that date, Monday, June 12, 1893. 21

The handkerchief in the papers

The newspapers routinely took the testimonies from the hearing and trial and paraphrased them to give them an interesting flow, almost like conversation. For some reason our bloodstained handkerchief was given some prominence as it was described to the reading public. At the beginning of the preliminary hearing, four separate news items, dated August 25, 1892, “quoted” Dr. Dolan’s description of Mrs. Borden’s crime scene, with emphasis on this mysterious cloth:

There was a silk pocket handkerchief on the floor near her head; it was an old one and I could not tell whether it was cut; but it was torn. –Fall River Herald.

Her body was lying on the floor, face down. She was dressed in a calico dress; a silk handkerchief was lying on the floor nearby, such a handkerchief as is used when a person is dusting. I cannot say if the handkerchief was cut. There was blood on the handkerchief. –Evening Standard.

He saw the body of Mrs. Borden very soon after he saw that of her husband. A handkerchief was over her head, but he could not say whether or not it was torn, it was so old. –New York Times.

I saw Mrs. Borden’s body a few moments later. It lay on its face on the floor of the room in the northwest corner of the house, second floor, between a bed and dressing case about 4 or 5 feet. Mrs. Borden was dressed, as you would expect to find a housewife at that time of day. Had an old handkerchief around her neck almost touching her head. It was bloody. It appeared like the handkerchief that women sometimes wear on their heads when dusting the room. Don’t believe it was tied in a knot. Don’t remember whether it was cut or not, know it was an old handkerchief. –Fall River Daily Globe.

A concerned citizen, obviously affected by the news coverage, wrote a lengthy letter to District Attorney Knowlton in the latter part of 1892 with his theory of the case and a possible use for the handkerchief: “I have an idea this poison was given in a handkerchief to the nose as chloriform [sic] & then the hatchet was used—because her mother would have struggled & yelled—calling the attention of the servant girl.”22

By the end of the first week of the trial, June 9, 1893, several papers had promoted the theory that “The government will endeavor to connect this handkerchief with Miss Borden if they can.”23 While the Rochester, New York, paper called it “saturated” and the Providence Journal of that date called it “blood-stained,” both claimed that Lizzie Borden reacted in court to the display. The latter news agent described it as having a “gory and horrid appearance” and says, outright, that “its presentation was dramatic” and had “driven its vivid way into the minds of all.” It continued on, though, to represent the item as having “no importance” to the prosecution—that although it might have been inferred it “was the property of the prisoner,” Mr. Moody will disappoint the public by emphasizing “that the handkerchief is one of a number of articles picked up about the remains of the murdered couple, and is just as important as any of these and no more.”

This is a good example of the ambivalence surrounding this piece of evidence so far in the case. Is it something, or is it nothing? Lizzie had reacted to it apparently, but the prosecution did not capitalize upon that.

The following week, in the papers of June 13, 1893, Dr. Dolan’s appearance at the trial was reviewed, again with reference to the handkerchief. “The blood-soaked rag was [again] exposed to the view of all” along with “all the gory relics of the murders,” describing the introduction in the court of “a large square of carpet, its original color gone in the discoloration it had received. It was the carpet upon which there had rested the dead body of Mrs. Borden and all the while these ghastly articles were in the view of all, the Prisoner’s Features Were Hidden Behind the Friendly Fan.”24

The Boston Globe of June 13, after Dr. Dolan’s testimony, summed up thusly: “this handkerchief, which was produced, had been buried with the other clothes, and had subsequently been dug up for exhibition at this trial. When Dr. Dolan shook out the handkerchief, all covered with blood, Miss Lizzie, hot and flushed and puffy, shrank into herself, covered her face with her handkerchief and nervously moved backward and forward.”

On June 14, 1893, the Fall River Weekly News, under the sub-headline “A Blood Stained Handkerchief” intimated this item belonged to Lizzie, but allowed the caveat that since she was a family member, and in her own home, there could be a simple reason for its presence in the guest room. This even-handed effect was spoiled by the last comment “that the State may attempt to show that this was one of the very handkerchiefs Lizzie ironed that morning.” Statements like this prove that the prosecution had not yet come to terms with the item, and the newspapers noticed.

The trial and aftermath

A crucial, though understated, moment in the trial came when Mr. Moody for the prosecution recalled Bridget to the witness stand on June 14, 1893. He had two main questions for her, one being her impression of this object, making the claim that “it was not here, or under our control at the time the witness was on the stand,” although it was State evidence since Allen had appeared on June 8. Bridget had also been questioned on June 8, but she had preceded Allen. The handkerchief had been part of the crime scene and given attention in the press since 1892, yet this recall came very near the end of the prosecution’s case. As an expert on the Borden’s laundry and cleaning habits, Bridget was asked, “Have you seen such a handkerchief as that before? (Showing dark, old handkerchief).” Bridget, not identifying it specifically, replied, “Yes, sir.” Moody followed with, “What was it commonly used for and by whom?” Bridget answered, “Mrs. Borden used to use handkerchiefs the same as dusters is.” “Did she [Mrs. Borden] use it as a pocket handkerchief?” Bridget answered obscurely, “Mr. Borden used them as pocket handkerchiefs and Mrs. Borden when they got worn out, took them as dust rags.”25

Silk would not be a fabric of choice for dusting, and a tattered silk would not afford much protection to the hair. Bridget did not identify that specific handkerchief as belonging to the household, but it seemed important to the prosecution, very tardily, to give it that status. The strategy is strangely obscure. However, a somewhat spurious claim now seemed to have been made, and from then on it is linked to Mrs. Borden herself, and as such has gone into lore.

On Thursday, June 15, Mr. Knowlton was about to rest the prosecution’s case. He prefaced that announcement with his offer:

We offer formally now, if we have not done so before, all the plans —I think they are already in the photographs, —I think they are already in, and the various exhibits that have been produced and identified by the witnesses, a list of which we can give if desired. That includes all the hatchets, including that without a handle, the two skulls, the dresses or the dress, skirt, the various pieces of the house, marble slab, piece of plastering and the bed clothing and the pieces of carpet, and also the things that were produced by Prof. Wood, —the piece of pear skin. I should have to examine the trunk to know if there is anything more. If my friends desire me to examine it, I will do so. I also offer the basket and box which came from the barn, and the handkerchief. I think that is all I remember now.

If the handkerchief was Abby’s, why not prove it sooner? If it was proven to be Andrew’s, why not say so the first week of the murder? If they could have linked it to Lizzie, then they would have. It had become a liability. It is likely that, lacking any proof of ownership, and in order to discount that any outsider brought it in, they finally determined to reduce its importance, through Bridget’s recall testimony.

On June 20, the jury was given some selected items to ponder during their deliberations. Some of these were “plans and photographs marked as exhibits in the case. Skulls of Mr. and Mrs. A. J. Borden. Bedspread and pillow shams. Handkerchief found by Mrs. Borden’s body.”26

In that courtroom, that is exactly what the artifact was, and nothing more: a “Handkerchief found by Mrs. Borden’s body.”

The sad but fascinating saga of the migration of this mysterious piece of silk, from lonely companion to Abby Borden’s body at the place of her gruesome murder, to this stately courthouse jury room in New Bedford almost a year later, nears its end. The jury barely considered the testimonies, hardly took the time to review the artifacts, probably did not even touch upon this shredded relic that seemed for so long to have an ambiguous place in the context of the case. It was not really clear what it was, who it belonged to, or how or why it was found in the guest room on the murder morning. After the “not guilty” verdict, Knowlton received a letter on June 24, from an interested attorney named John Goldsmith of New York, still asking hard questions that were evidently in the collective minds of the populace now that there was no longer a viable suspect in the case. The author wanted Knowlton’s opinion: “Do you believe that Lizzie Borden used the handleless hatchet to kill, and then broke off the handle? . . . Do you believe she wore that handkerchief around her head, which was found saturated with blood near Mrs. Borden?”27

The end of the trail

In 1893, Edwin Porter, a Fall River Globe reporter who was actually present in the house the afternoon of the murders, wrote a book that was the first complete study of the mystery: The Fall River Tragedy. He included a few references to the handkerchief in his review of the testimonies. In 1961, Edward Radin published Lizzie Borden, The Untold Story, which used paraphrased testimony to introduce the handkerchief. His treatment, however, gave the bold statement that “Bridget Sullivan made a third, but brief appearance on the stand. A large colored handkerchief had been found near Mrs. Borden’s body. Police thought she had been wearing it as a dusting cap but it showed no cut marks from the murder weapon. Bridget explained that it was one of Mr. Borden’s old handkerchiefs and Mrs. Borden liked to use it as a dusting cloth.”28 Radin had access to similar material used here in this history of the handkerchief. It is obvious that he made his own determination as to what the object was, based on his interpretation of Bridget’s reply at the trial, upon her recall to the witness stand.

In 1956, Agnes de Mille visited the Waring family in Fall River with Joseph Welch to conduct research for an upcoming television broadcast on the crime and trial. The daughter of Andrew Jennings, Lizzie’s defense attorney, gave them access to what became known as “The Hip-bath collection”—relics of the famous murder trial that Jennings had brought home and preserved in an old hip-bath tub. Amongst the items stored there de Mille found “the switch of Mrs. Borden’s hair, a dirty brown color (few gray hairs) with the straight, old-fashioned hair pins still in place—‘what my mother would have called a rat,’ said Mr. Welch. This was matted and soiled with dried blood. It had been loosened from her head by the blows and lay on the floor beside her. There was the kerchief, stiff with blood, that she had been wearing over her hair.”29 This description of the blood may have been an assumption (if she did not handle it), Jennings’ family lore passed on to her, or the result of her own examination of the object. In addition, once the few items mentioned were stored together—handkerchief, pins, and hair switch, they ever after became integral with each other and considered closely associated.

A 1968 photograph at the Fall River Historical Society from their Borden case archive shows these items together, the handkerchief in a crumpled state, not fully exposed. Miss de Mille published a book on her project in 1968, and that same year saw the “Collection” donated to the Historical Society. Barbara Ashton looked the collection over, made notes, and published her review in Proceedings, as part of the presentations made at the 1992 Centennial Conference on the Borden case. Her notation #4 has this description: “Hair switch and Bloody Handkerchief: worn by Mrs. Borden at the time of the murders,”30 which promulgates de Mille’s assessment, and Radin’s conclusion.

In this century, in 2004, the artifact has more recently come under scrutiny while under the spotlight of a camera crew and the inspection of two seasoned forensic officers. Morningstar Entertainment was filming the television presentation Lizzie Borden Had An Axe. The crime scene experts carefully unfolded the handkerchief wearing white cotton archive gloves, laid it out in display, and scrutinized it. They were allowed to inspect the handleless hatchet head that is also housed at the Historical Society. One fit the blade to a tear in the silk material and seemed very pleased with the result. It was a spontaneous and casual examination. It was good television, but they knew no serious deduction could be reached at this late date, taking into consideration the tattered state the fabric was in. Amazingly, the item appeared somewhat clean and unstained by blood as it was laid open to the lights.

By studying the history of the artifact, the result is that there still are questions here—ones that might never have an answer this late in the object’s life. But it certainly does have value: even if it was innocent of intent, it had been covered with the victim’s blood. It could have been used as a head scarf by Abby, and dislodged during the attack. The killer could have worn it to protect their face from recognition or to cover their hair to keep out the spattering of blood. The person who used it could have been another family member, a stranger, or Lizzie herself. It could have normally resided in Abby Borden’s pocket as she did her daily housework and taken by the assailant to wipe the bloody hatchet, then dropped on the floor as refuse. It might have been used by one of the doctors on site to wipe their bloody hands after putting their fingers in the wounds, and therefore moved. It might have carried the blood of the attacker, as well as that of Abby Borden.

But, where are the other items from the crime: the carpet piece, the roll of cotton batting, the napkin, apron, drawers, chemise, or Andrew’s necktie and truss? Because very few pieces survived the century betwixt the crime and now, we are lucky to have this handkerchief—it stands as a mute witness to the butchery of Abby Borden.

What follows is a short interview with Assistant Curator of the Fall River Historical Society, Dennis Binette. He graciously offered myself, Harry Widdows, and Stefani Koorey, our first view of the controversial artifact in the archive room on site in August 2007. Stefani and I had appeared in the video Lizzie Borden Had An Axe that premiered the handkerchief to the television viewing public, and after that, I always had questions about it. Mr. Binette was kind enough to answer these. Many thanks go to the curators, Mr. Martins and Mr. Binette, for the attention they give to the preservation of priceless artifacts such as those of the Borden case.

Do you have any more background on the handkerchief?

We have no additional information on the handkerchief.

Who received it into the collection?

The item was received into the collection by Mrs. Mary B. Gifford, who was curator of the Historical Society at the time.

Did it come with the hair switch and hairpins, all wrapped together?

Not having been at the Historical Society at the time, I have no idea as to how the items were packaged when received.

If the handkerchief had been “stiff with blood,” do you know who cleaned it, if it is, indeed, clean?

The piece has never been cleaned while in the possession of the Historical Society. It is in the condition it was in when it came into the collection.

Did it come into your collection as part of the Waring Hip-bath donation?

The handkerchief was one of the items that comprised the “Hip-bath Collection.”

When did you and Michael Martins first see it?

Both Michael and I saw the piece for the first time when we came to work at the Historical Society. It was on display as part of the Borden exhibit at the time.

Did it always look like it does now (clean, with shreds), since it came to you?

It has always been in the condition that it is now. It is the nature of the fabric to break down over time, especially considering the acid content in the dyes that were used. Splitting in general, especially along creases or folds, is often found in period fabrics of this type.

What do you call the thing, and why?

We don’t call it anything in particular. The late Mrs. Florence Cook Brigham, when curator of the Historical Society, always said that it was a dusting scarf, worn by Mrs. Borden while she did the housework. The piece would be worn on the head and knotted. It appears that this is how Mrs. Gifford referred to it.

Did the handkerchief come to you with hairpins attached to it, as if it had been worn with pins? Or did loose pins from the hair switch migrate into the cloth, in your estimation?

Since neither Michael nor I were associated with the Historical Society when the switch and handkerchief were received into the collection, there is no way of knowing how the items came in. As the hairpins remain in situ on the switch, it is likely that there were none present on the handkerchief, as there would be no reason for them to be removed if they were, in fact, attached to the artifact.

Has that handkerchief ever been on display?

The handkerchief was on display for years, but removed because of its fragile nature.

Where do you keep it?

The handkerchief is kept in storage.

Does it seem like a man’s old handkerchief to you?

The piece resembles a decorative handkerchief or scarf. Generally, one thinks of a functional handkerchief as made of cotton, a much more durable fabric than silk.

About the hair switch:

Is there anything you can elucidate about the switch? Is it made from Abby’s own hair, or a false hair? If a false hair, is it human hair?

The switch has the appearance of human hair. It is not coarse like horse or animal hair. Whether it was constructed of Mrs. Borden’s own hair is not known. Although it was common for women to save stray hairs from their hairbrush in a receiver so as to have extensions made, it was also just as common to purchase ready-made pieces. The Fall River city directories actually had a category for vendors in “Hair (Human)” in its listings.

Is the hair switch still bloody or was it cleaned, and by whom, do you know?

The hair switch has not been cleaned. According to its donor, Mrs. Waring, the switch was taken by her father, Attorney Jennings, and brought home. As one of a collection of physical evidence, it was stored in the family home, but nothing was done with it until it was donated to the Historical Society. It is currently in the condition it was in when added to our collection.

Do you have any other “lore” or info, or anecdotes, on the handkerchief?

No. No lore, no anecdotes. Just the facts.

Endnotes:

1 Burt, Frank H. The Trial of Lizzie A. Borden. Upon an indictment charging her with the murders of Abby Durfee Borden and Andrew Jackson Borden. Before the Superior Court for the County of Bristol. Presiding, C.J. Mason, J.J. Blodgett, and J.J. Dewey. Official stenographic report by Frank H. Burt (New Bedford, MA., 1893, 2 volumes), PearTree Press, Harry Widdows, Stefani Koorey, 2004, 439.

2 Trial, 440.

3 Preliminary Hearing in the Borden case before Judge Blaisdell, August 25 through September 1, 1892. Fall River, MA: PearTree Press, 2005, 90.

4 Preliminary Hearing, 407.

5 Preliminary Hearing, 29.

6 Preliminary Hearing, 184.

7 Trial, 135.

8 Preliminary Hearing, 241.

9 Preliminary Hearing, 11.

10 Inquest Upon the Deaths of Andrew J. and Abby D. Borden, August 9 – 11, 1892, Volume I and II. Fall River, MA: PearTree Press, 2004, 58.

11 Inquest, 63.

12 Trial, 593.

13 Preliminary Hearing, 197-8.

14 Inquest, 139-40.

15 Trial, 121-23.

16 “Enveloped in Mystery,” Providence Journal, 6 August 1892.

17 “Visited the Tomb,” Fall River Herald, 8 August 1892.

18 “Enveloped in Mystery,” Providence Journal, 6 August 1892.

19 “Visited the Tomb,” Fall River Herald, 8 August 1892.

20 “The City. A Burial,” Fall River Evening News, 17 August 1892.

21 Trial, 857-9.

22 Commonwealth of Massachusetts VS. Lizzie A. Borden; The Knowlton Papers, 1892-1893. Eds. Michael Martins and Dennis A. Binette. Fall River, MA: Fall River Historical Society, 1994, 143.

23 Crowell Collection, possibly New York Press, 9 June 1893, also Providence Journal same date, also Fall River Weekly News 14 June 1893.

24 “Dramatic Picture,” Providence Journal, 13 June 1893.

25 Trial, 1237-8.

26 Trial, 1927.

27 Knowlton Papers, 325.

28 Radin, Edward. Lizzie Borden: The Untold Story. NY: Simon & Schuster, 1961, 151.

29 de Mille, Agnes. Lizzie Borden: A Dance of Death. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1968, 110.

30 Ryckebusch, Jules R., ed. Proceedings: Lizzie Borden Conference. Portland, ME: King Philip Publishing Co., 1993, 214.