by Richard Behrens

First published in November/December, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 4, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

I. The Death of a Prostitute

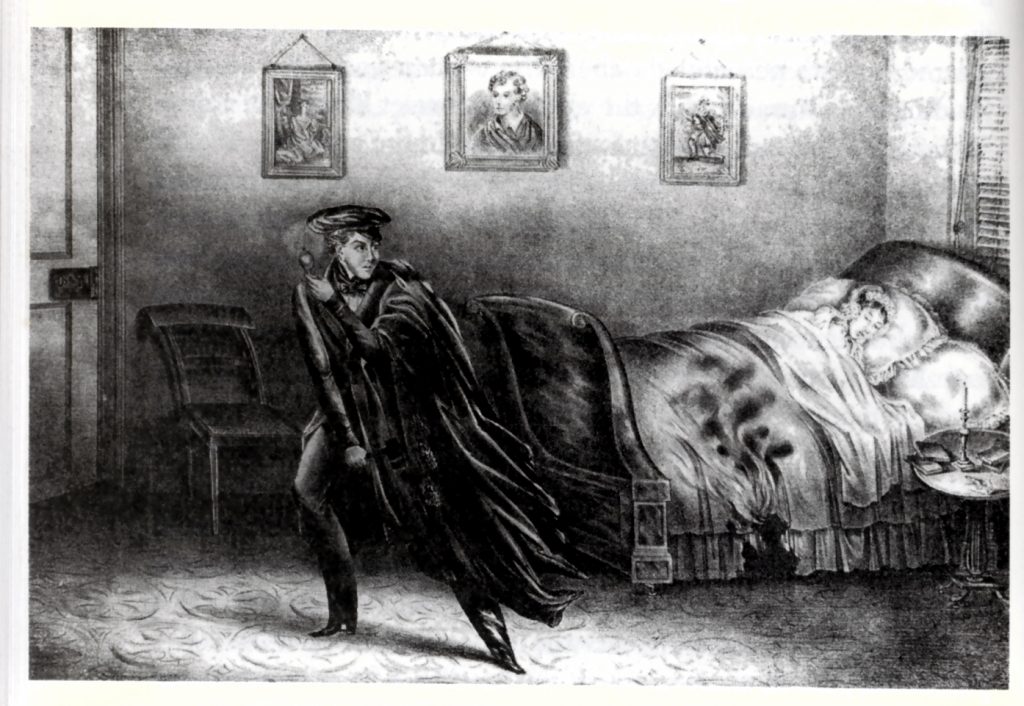

Late in the evening of 9 April 1836, Rosina Townsend, the madam of an upscale New York City brothel at 41 Thomas Street, not too far from the future site of the World Trade Center and just west of Broadway, was presented with an unusual request from one of her more popular prostitutes, Helen Jewett: to deny admission to Helen’s regular Saturday night client. Instead, Rosina was told to expect a man by the name of Frank Rivers, who had been seeing Helen since the previous summer and with whom she seemed to be having much difficulty. Indeed, sometime between 9 and 9:30 p.m., Frank Rivers appeared at the brothel, his face covered by a cloak, and, with hardly a word of greeting, briskly disappeared into Helen’s second floor bedroom. Rosina saw Frank again after 11 p.m., when she delivered champagne to the room; after which, she joined her own guest for the night, and at a quarter past twelve, went to bed.

Awakened at three in the morning, Rosina noticed that a globe lamp was on a table in the parlor at the back of the house that should have been in Helen’s room, and that the door to the rear yard was ajar, a clear violation of the house’s protocol. Pushing through the oddly unlatched door of Helen’s room, Rosina was shocked to find billows of smoke, and Helen lying on the bed, “her nightclothes reduced to ashes and one side of her body charred a crusty brown,” by the flames that were consuming the mattress [Cohen 7].

Pandemonium erupted in the brothel on Thomas Street: watchmen were called from the street (New York did not yet have an organized police force); male clients of the other prostitutes hastily pulled on their trousers and fled into the night; and the surviving women labored to extinguish the flames that threatened to engulf the building. After all was over, they were left with the burnt body of what had previously been a twenty-two-year-old prostitute.

Jewett had been hit three times on the forehead with a hatchet, two light blows followed by a heavy one that cracked into her skull, killing her instantly. Blood in her thoracic cavity told the coroner that she had been dealt a heavy blow to the chest, perhaps the result of being held down brutally while the killer attacked her face with the hatchet. There was little doubt that the extensive burns to her body happened after her death. The killer may have intended to burn down the brothel, thereby erasing evidence of his crime.

A horrified Rosina Townsend told all who would listen about Frank Rivers and his late night visit to Jewett. He was last seen lounging in Jewett’s bed, just three short hours before the discovery of the body. Townsend had observed him from behind, but had noticed a bald spot on the top of his head, a detail that helped identify him. Others who worked at the brothel named, as being amongst that night’s visitors, a nineteen-year-old clerk, Richard P. Robinson, who lived in a boarding house at 42 Dey Street.

Two constables arrived at the boarding house, pulling Robinson out of bed and placing him into custody. Appearing blank and dispassionate, Robinson claimed that he had arrived home the night before after 11 o’clock. His roommate, another young clerk who was a frequent visitor to the Thomas Street brothel, backed up his alibi, claiming that he had awoken at 1 a.m. to find Robinson in bed. Both were brought back to Thomas Street and unceremoniously paraded before the remains of Helen Jewett. Robinson remained stoic and unflinching, consistently denying the allegations against him. By early morning, he was in Bridewell jail in Lower Manhattan, stridently protesting the injustice that was being done to him.

As the case unraveled and the press became more involved, it was clear that this act of homicide was not, as violent as New York was at the time, typical of the city’s criminal activity. Helen Jewett was a well-known prostitute who worked at a wealthy brothel; she was frequently seen parading down Broadway in her characteristic green antebellum attire, a style of which she owned many splendid examples. Jewett also counted amongst her clients some respectable New Yorkers, and not merely the young clerks typified by Robinson. Here was no mere streetwalker: Rosina Townsend’s establishment was situated in the same neighborhood as Park Row, Columbia College, New York Hospital, the Astor House (owned by John Jacob Astor), and the College of Physicians and Surgeons. The close proximity of Columbia students and wealthy doctors guaranteed the prostitutes of the area respectable clients with reliable cash flow, unlike the more degenerate women who haunted the back alleys of Five Points and Corlears Hook (from which locale the name “hooker” came to be applied to women of that profession).

So, very rapidly, Helen Jewett and Richard P. Robinson seized the public’s imagination. The press coverage was both lurid and sensational, and the attention of America (barely sixty years old) began to turn to the bizarre tale of the store clerk and the prostitute.

II. Sex and the City

Richard P. Robinson was from a moderately successful Connecticut family, and had come to New York City to apprentice himself in a trade and to seek his fortune. He was a typical example of the sporting male sub-culture that had arisen in the 1830s, of the young men who lived in boarding houses where their private world would remain unmonitored by adults that are more responsible. These sporting boys cultivated an aggressive male dominance over women, preferred bachelorhood to marriage, and a long-standing financial arrangement with a prostitute over any sort of committed relationship. As time progressed, this sub-culture even generated its own newspapers: the Whip, the Flash, and the Libertine; this community of rakes even printed its own guides to the city brothels, publications that were little better than consumer reports about the women who were their purchased merchandise. Richard P. Robinson, thrust into the public spotlight by his dramatic arrest, the sensationalism of the murder charges, the revelations of his letters to Helen, and by his puckish and non-repentant attitude during his incarceration and trial, nevertheless would become a pronounced symbol of this sporting culture. Indeed, Robinson came to embody a defense of the group’s principles, and an affirmation of the antebellum youth culture of libertinage.

Sometime around 1820, New York City had emerged as a major center of commercialized sex. Prostitution had evolved from a marginalized phenomenon of the working class to an economic trade that was an integral part of city life. One of the major contributing factors to this evolution was the privatization of much previously held municipal real estate, which placed, to a degree theretofore never experienced, economic and cultural development issues into the hands of landlords. These investors were struggling with the effects of a tidal influx of immigrants, an unprecedented migration of poor people into New York, a phenomenon that gave rise to the tenement culture. It made sound economic sense for landlords to place more faith in the ability of a well-managed brothel to pay the high rents they demanded, than to rely on the questionable resources of the working class poor. As New York City rents increased (scandalously so: livable apartments were renting for several times the annual salary of a typical laborer), both the exploitation of large masses in the tenements, and the unusual license and privilege extended by landlords to brothel madams, became acceptable infringements of the social order that were readily overlooked by the law. In fact, New York barely had any anti-prostitution laws on the books in the 1820s. Accordingly, the proliferation of the profession throughout the city, even in well-heeled neighborhoods like Park Row and Water Street, was greatly stimulated by a legal tolerance that protected the investments of the landlords who owned the buildings in which the brothels enacted their business.

John R. Livingston, for example, was the landlord who owned the Thomas Street property in which Helen Jewett was murdered. Livingston had rather substantial real estate holdings. He came from a wealthy family that included Robert Livingston, a founding father, Chancellor of New York, and one-time minister to the court of Napoleon. Garnering a reputation as a war profiteer during the American Revolution, John R. Livingston had secretly sold out to the British, at one time working in cahoots with Benedict Arnold—later distancing himself from his business partner when Arnold’s traitorous plans were revealed in 1780. Livingston, who once said, “Poverty is a curse I can’t bear,” then became a New York real estate investor, coming to own much of the property that constituted the Five Points, one of the most crime-ridden and dangerous slums in the city. Over the first half of the 1800s, he had been the owner of thirty brothels in total, including many of the most fashionable and lucrative. The Madams had an unholy alliance with him, and while circulating their business through many Livingston properties, the number of protesting neighbors increased. Other wealthy families, including the Lorilards, followed Livingston’s profitable example, since owning brothels tuned out to be quite a sound real estate investment. Indeed, the brothels’ economic viability was a principal reason why so few anti-prostitution laws were passed by the city [Gilfoyle 43].

Despite community protests and the increasing crime rate that formed on the periphery of the prostitution world, the industry flourished as a collaboration in a symbiotic relationship: the wealthy landlords who rented the houses; the municipal government who turned a blind eye to the thriving sex trade; the affluent clients who wanted sex; and the young women themselves who needed the profession as a way to survive in a harsh capitalist world. The combined efforts of law enforcement, religious leadership, and community action all failed to curb the rapid growth of the sex trade.

The theater houses in New York, such as the Park Row and the Bowery, were notoriously saturated with ladies of the night since they often used the convenient darkness of the theater stalls to arrange amorous and sexual liaisons. The “third tier” was an infamous denotation for the upper balcony of these theaters, a territory where such women patrolled freely, undisturbed by law enforcement and isolated from the more dangerous life of street-walking. Here, amidst the cacophony of actors on stage, musicians in the orchestra pit, and the roar of the audience (who often treated the theater more like a social picnic than a place to passively watch a work of art), the young sporting men cruised for their sexual liaisons. Richard P. Robinson’s letters to Jewett, found under her bed after her death, made constant reference to their encounters at the theater. They had clearly found this to be a place they could meet privately to make sexual plans for the evening.

As more successful madams like Rosina Townsend gained prominence, many brothels were going private, with arrangements being made by appointment only, and with the cost of services increasing to the point that a courtesan like Helen Jewett became wealthier than many of her contemporaries—the mainstream women who had resigned themselves to more respectable, but less remunerative, professions. Some of the lower-class gangs of youths took exception to this and the violent, disturbing practice of brothel raids began. These unprovoked attacks were Clockwork Orange-style assaults on private houses, where drunken, angry men with bats and knives would force the prostitutes to serve drinks, then they would terribly abuse them and vandalize the property. The brothel raids were increasing in frequency around the time of Helen’s murder, which was the main reason for Townsend’s having employed such a tight security protocol on the evening of 9 April.

At first, the case against Robinson seemed open and shut. Witnesses saw him with Jewett right before her murder and he was the last known person to see her alive. The security at the brothel necessitated that a lady of the house let out midnight visitors through the locked exits, but no lady had reported letting Robinson out at any time. The only way he could have escaped was through the back door, which had clearly been opened by someone from the inside after a globe lamp from Helen’s room had mysteriously found its way downstairs. In the courtyard beyond, a cloak was discovered similar to the one Rosina that had seen Rivers wearing, and a hatchet was found discarded near the rear wall. This was determined to have been the weapon that ended Jewett’s life and was similar to one that had gone missing from the grocery store in which Robinson worked. Few were in doubt that Richard P. Robinson, a.k.a. Frank Rivers, had done the deed, and a coroner’s jury thrown together at the crime scene confirmed this belief.

Under ordinary circumstances, such a crime would have passed notice in the obscure filing cabinet of crime statistics, hardly worth a second thought, but this one struck a particular note, touching the raw nerve of several social and cultural conditions that were unique to the age. Robinson, as a representative of a privileged middle-class youth population, soon had a large number of supporters who believed in his innocence. That these supporters were themselves mostly young men who frequented prostitutes was no cause for surprise. Helen, further, was hardly like the ordinary profile of a prostitute. She was an educated woman who had a passion for literature, poetry, and the performing arts. Her room was stocked with novels and books of poetry, and the wall over her bed boasted a portrait of Lord Byron, itself an expression of her erudite romanticism.

The sensational details of the relationship between Robinson and Jewett, which had been going on for almost a year, before she had ever started working at the upscale brothel, were revealed in the letters found at the crime scene. The psychological scope of this correspondence was worthy of a tragic novel: the complexities of their feelings for each other, Robinson’s outrageous bouts of jealousy and anger, coupled with Helen’s coy and manipulative game-playing, shocked many readers who had presumed that young men only saw prostitutes for hastily-performed sex acts and nothing more. This rare peephole into the world of antebellum “yuppies” and their sensual lifestyle was cannon fodder for the news journals and penny sheets, which exploited the situation with unprecedented news coverage sparking a nation-wide media sensation.

James Gordon Bennett of the New York Herald was one of the few newspaper editors who made an appearance at the Thomas Street brothel, personally interviewing Rosina Townsend and the other prostitutes. He also viewed the body, vividly portraying to his readers his impressions of Helen’s corpse:

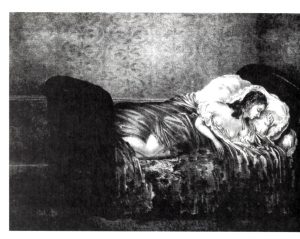

Not a vein was to be seen. The body looked as white—as full—as polished as the pure Parian marble. The perfect figure—the exquisite limbs—the fine face—the full arms—the beautiful bust—all—all surpassing in every respect the Venus de Medicis. . . . For a few moments I was lost in admiration at this extraordinary sight—a beautiful female corpse—that surpassed the finest statue of antiquity [Cohen 16].

However, below all this idealization of Helen’s prostate form, Bennett neglected to describe her mutilated face, or to mention the horrible burns on her body. Nor did he disclose the fact that, shortly before he viewed her, she had been autopsied, with her breasts parted thus by a hideous gash from the coroner’s blade. Such were the distortions of the sensational press that had begun full force to exploit the tragedy.

Bennett did have one advantage, however, relative to other reporters: his physical presence on the scene and his contact with the prostitutes who had known Helen (not to mention the possibility that he was also a client at the establishment), gave him the scoop on her real identity.

III. Dorcas Doyen

Bennett thus identified Helen Jewett as Dorcas Doyen from Augusta, Maine, a poor “virtual” orphaned girl who had been taken at age thirteen into the home of State Supreme Court Justice Nathan Weston (her father and stepmother lived nearby but could not take care of her). So placed, Dorcas was raised in a cultured, upscale environment. Dorcas had also been graced with the advantages of a quality education, due to the generous nature of Judge Nathan and the fact that his father-in-law had founded the Cony Academy, one of the country’s first boarding schools for young girls. Despite her humble origins, she had spent much of her younger years in middle-class surroundings, albeit as a servant.

The judge himself found out about Helen’s murder from an Augusta newspaper and was shocked to discover that the fallen woman found murdered in a New York brothel had been the little girl that he had sheltered until the age of eighteen. It was only a matter of time before Helen’s journey from Maine to Thomas Street was made public, and a portrait emerged of a woman that was as unlike any ever associated with the profession of prostitution.

Dorcas’ family could be traced back to the French Huguenots who had fled France to the New World. Her ancestors’ early trials in the wilds of New Hampshire, before the American Revolution, remain largely uncharted since they did not distinguish themselves in the historical records. Jacob Doyen, her grandfather, fought hard in the war, having been wounded in the battle of Saratoga; he wintered at Valley Forge with George Washington, and finally engaged in grueling and savage combat with the Iroquois Indians in the Finger Lakes region of New York. In the 1780s, he settled near Augusta, Maine, where his registered profession was that of hog reeve (a man who gathered wandering hogs), a not-too-distinguished office for a man in a frontier society bristling with opportunities for the industrious.

John Doyen, Jacob’s son, who was recorded in history as a shoemaker, brought Dorcas into the world on 18 October 1813. She was named after a saintly woman in the Bible who performed charitable work for the poor, and, indeed, at that period in history, many women’s charity groups were called Dorcas Societies. Ominously enough, Dorcas was also the woman in the Bible whom Saint Peter had resurrected from the dead in the Book of Acts.

Sometime between the age of seven and ten, Dorcas’ mother died and her father chose to put her into service, placing her with a prominent Augusta family who boasted the largest private library in the state. This situated the working-class Dorcas within the influence of cultured living and education. When she was thirteen, her services were transferred to the family of Judge Nathan Weston who made a deal with Dorcas’ father that he would house and support her as his girl servant until she reached the age of eighteen, a favorable prospect to her father as this would ensure that Dorcas would come of age associated with middle-class respectability.

By that time, Augusta itself had grown in but a few short decades from a frontier fort community to a thriving and civilized society, now home to two learning academies, banks and bookstores, newspaper offices and law firms. Powerful families like the Bridges, the Williams, and the Westons had forged a gentile antebellum society on the landscape that had once been a wild frontier. Dorcas may have been scrubbing dishes in the kitchen and running laundry most of her day, but she did so in a privileged atmosphere. She attended the First Congregational Church and went to school with a sponsorship from Judge Weston. Further, she got to observe the daily affairs of a distinguished family, whose sons themselves would later become, respectively, a Senator and a Supreme Court Justice. Dorcas was also rapidly developing a devouring passion for books.

One of John Adams’ main visions of America was a nation of literate people, whose education would make them worthy of exercising a true voice in a democracy. In 1823, when Dorcas came to Augusta, these ideals of Mr. Adams, who was still very much alive, were freshly minted upon the American imagination. In such fashion, Augusta, which was petitioning to be made the capital of Maine, boasted not one, but two bookshops. One of these, just a few short blocks from Judge Weston’s house, was run by Harlow Spaulding, a young man who helped to raise the intellectual level of the town through his literary and bookselling efforts. His bookstore boasted newly printed books, including novels, which were still a controversial art form in the 1820s. It was then particularly believed that romanticism and novelistic fantasy had a corrupting influence on the young, since it was perceived as encouraging impressionable minds into flights of fancy. Lord Byron, whose works were sold at Spaulding’s store, drew particular criticism, and Dorcas’ love for the romantic writer’s stormy works was evident at her death scene more than a decade later—her scorched and mutilated body lay under a portrait of the poet. Spaulding’s initials were the same as the ones used in a article run by the New York Herald in 1836, which claimed that Helen Jewett had been corrupted by an “H—- S——g,” a seduction that was portrayed as having led to Dorcas’ fall from grace and her descent into prostitution.

While it cannot be proven that Harlow was Dorcas’ lover and such a corrupting influence, there is no doubt that they knew each other, for, in any event, Dorcas’ love for books would have inevitably drawn her to Spaulding’s store. There Dorcas had access to writers like Walter Scott and Washington Irving, not to mention the works of Lord Byron. Anne Royall’s Black Book trilogy, a non-fiction account of the travel author’s experiences in Augusta, a book series that was also to be found in Spaulding’s store, actually boasted an encounter with little Dorcas in the household of Judge Weston. This was to mark Dorcas’ first appearance in print, though sadly, it was hardly her last.

In 1828, Spaulding’s bookstore proudly presented the first novel by Nathaniel Hawthorne, a work that actually premiered on consignment at Harlow’s. In fact, Hawthorne’s literary agent was also cited by the New York press as having been Dorcas’ alleged corrupting lover. Years later, Hawthorne was to visit a wax exhibit in Boston depicting Helen’s murder and wrote about it in his American Notebooks. History does not record if Hawthorne then had recognized her as Dorcas Doyen, the servant girl from Augusta, Maine.

Although there were a few other candidates besides Harlow Spaulding who may have qualified as the man who had seduced Dorcas (and in the eyes of antebellum society, once a woman was seduced by a man, she was seen as a fallen woman—not so for the seducer, apparently), it is clear that there was someone who was intimate with her, emotionally as well as physically. In a letter to Robinson many years later, she wrote, “I have met very few persons who could share in all my feelings so largely as——, who was my earliest companion. When I walked, read, or conversed with him, I whispered to my heart, if I could find one like him how much I should love him” [Cohen 193].

Although Dorcas was prone to weaving fantasies, fabricating false identities, and exaggerating the truth, it was clear that she had been seduced by someone and that this fact was brought to the attention of Judge Weston. When the Judge forced her to leave his home, she fled initially to Portland, and later to Boston, surviving, despite her young age, by learning the trade of prostitution. For three years after leaving Augusta, she wrote back and inquired often about Harlow Spaulding, the young bookseller who, subsequently, in 1836, would vehemently deny having had any association with the dead prostitute in New York, but who may very well have been the one true physical and intellectual love of her life.

IV. The Sporting Boy

From the moment that Helen Jewett was murdered and Richard P. Robinson was taken into custody, Helen and the sensational details of her life and death particularly fascinated the newspapers and the public; hardly any attention was paid to the accused. However, there was much to find that was sensational in Robinson’s life.

Regardless of his guilt or innocence, Robinson was an example of a new breed of young American men. He exemplified those from respectable backgrounds who had come to a big city to apprentice themselves for a white-collar career, but, who, unlike their eighteenth-century predecessors, were living on their own in boarding houses. These sporting boys led lives that were unmonitored by families or employers, freely indulging themselves in libertine lifestyles that involved affairs with prostitutes (sometimes several at once), sporting events, gambling, and other such vices that rapidly-growing mercantile cities like New York had to offer. The image of Robinson spending his energies on a woman like Jewett, forming emotional and physical bonds with a woman who was continually manipulating him, who was flaunting her other lovers in his face and playing coy games with his emotions, is one straight out of a dark and stormy gothic novel.

The press virtually ignored him at first. Perhaps it was the fact that Robinson’s employer, Mr. Joseph Hoxie, a small business man and a local politician of the Seventh Ward, vouched for his young clerk as an upstanding gentleman and insisted that the boy’s alibi was sound; or perhaps it was the existence of Robinson’s middle-class family in Durham, Connecticut, that led the New York press to hold back on its reporting about the boy’s character and life-style. However, it was only a matter of time before the letters that Robinson had written to Helen, over a period of ten months, were revealed. Moreover, as events unfolded, Robinson began to appear as a disturbed man whose emotional condition worsened the more he struggled to turn his tryst with a prostitute into something resembling a real love affair.

Robinson’s roommates and fellow clerks also had affairs with the women of the Thomas Street Brothel. In fact, George Marston, who went by the name of Bill Easy, had been Helen’s regular Saturday night visitor, whom she had turned down on 9 April in order to receive Frank Rivers into her bedroom. Marston was an unstable youth from Massachusetts who had been accused of arson, and denounced by his family as a mindless dolt destined for self-destruction. Both Marston and Robinson were examples of what the moral reformers at the time were decrying as youths who were bringing themselves to ruin through their rakish lifestyles and voluptuous indulgences. They were the 1830s equivalent of the Wall Street yuppies of the 1980s, who also frequented prostitutes and had a dangerously unmonitored amount of money. Oddly enough, those yuppies, who were to ravage New York City in a similar vein more than one-hundred-and-fifty years later, worked and sometimes lived in the same neighborhood as Helen Jewett and Richard P. Robinson.

The story of their curious relationship, which began in June of 1835, is told through a series of some fifteen letters written by Robinson and some forty-three penned by Jewett. Oddly enough, only one of the letters out of the sixty-eight that were extant was admissible as evidence at Robinson’s trial, but all of them were published years later in the National Police Gazette. James Gordon Bennett of the Herald reported that actors at the Bowery Theater, the same venue so often frequented by Robinson and Jewett and which served as their secret meeting place for so many months, were performing passages from the letters on stage as if they were “a scene from Shakespeare” [Cohen 249].

The letters, as reproduced in the press, are curious and strange: certainly not meant to be read by any third set of eyes; definitely not revealing any back story (events are commented upon but not explained); and are replete with a large amount of emotional and psychological game-playing, especially from Jewett towards Robinson. After all, Jewett’s job required that she put on a mask and not dare reveal her true motivations or feelings. It is a testament to her professionalism that she devoted so much time to letter writing, particularly inasmuch as this activity was the administrative work of her relationships with her clients.

An early letter written on 20 June 1835, reveals how masterful Jewett was at hooking her new customer:

There is so much sweetness in that voice, so much intelligence in that eye, and so much luxuriance in that form, I cannot fail to love you. The pleasure I feel in your presence and your smile, speak of hour and nights of joy; I long to see you, to hear your conversation animate your features once again, but I must defer that pleasure until your next visit [Cohen 252].

It is clear from this passage that intense flattery is a mere prelude to a subtle suggestion that Robinson come back to visit her, presumably at $5 per night. Her affection for him, apparently, isn’t enough for her to demand his presence right away, but only during regular business hours at the brothel.

In subsequent letters, Helen is downright passionate about her alleged love for him, and even compares him to an unnamed lover from Augusta, the one with whom she shared her deepest feelings and with whom she had a deep intellectual relationship (this, perhaps, being Harlow Spaulding). Robinson’s response to these proclamations is over-the-top and perhaps even self-delusional: “At best we but live one little hour,” he writes in June of 1835, “strut at our own conceit and die. How unhappy must those persons be who cannot enjoy life as it is, seize pleasure as it comes floating on like a noble ship, bound for yonder distant port with all sails set. Come will ye embark?—then on we go, gayly, hand in hand, scorning all petty and trivial troubles, eagerly gazing on our rising sun, till the warmth of its beams (i.e. love) causes our sparkling blood to o’erflow and mingle in holy delight . . .” [Cohen 256].

In this heavily romantic and embarrassingly over-metaphorized passage, Robinson’s highly theatrical reaction and his bad imitation of Shakespeare demonstrates that he has taken much away from his visits to the Bowery Theater. The same letter, despite its descent into romantic fantasy, ends with a tinge of jealousy for another man: “Did Cashier come to see you after I left?” he asks [Cohen 257].

Jewett’s strategy at this point was to begin feigning her own unworthiness for Robinson’s love, as if she were preparing him for an inevitable break, or at least keeping him at a distance. She also began to dangle before him the reality of her other clients. In a letter in which she beams over how exhausted she was from a night’s love-making with Robinson, she ended with the anecdote of how she joined another client called The Duke and a few other prostitutes in breaking out some champagne bottles and having a party immediately upon Robinson’s departure. She ended another romantic letter with the ominous and jealousy-provoking statement that “the parlor is full of persons, and I am called off from writing . . .” [Cohen 260]. In other words, Jewett had other men downstairs in the brothel’s parlor who wanted to have sex with her.

Soon, Robinson’s pathology started manifesting. Perhaps it was more than a mere theatrical flourish when he wrote to Helen in June: “I am not without my bitter moments of dismal misery, when I loathed all, myself and everything on earth” [Cohen, 257]. And soon he would be writing to her of events whose true nature history must bar from our sight:

Helen, I must now again, beg your pardon, for my most ungenerous and ungentlemanlike conduct last night. You have always treated me well, too well, and why I should thus requite you, I myself know not. . . . When you told me you were unhappy and wished me not to act so foolishly, I felt for you, and pitied you, yet I could not have spoken a pleasant word, if I would [Cohen 261-262].

He ended the letter by reminding Helen that it was Bill Easy who had slept with her the night before, which implies that he had erupted into an irrational rage over her relationship with his fellow clerk.

Soon the tables would be turned when Jewett finds out that Robinson has been seeing another prostitute, and she writes him a restrained, but highly manipulative, letter:

There are very few men who understand the feelings of poor women. We are often obliged to smile and hide with a cold exterior, the feelings which sometimes nearly cause our hearts to break. Women only can understand woman’s hearts. We cannot, dare not complain, for sympathy is denied us if we do [Cohen 263].

She begged Robinson to come see her and explain his infidelity, but it is difficult, reading through the letters, to sense how much of her described emotions are genuine and how much reflects a prostitute trying to hold onto a client who is threatening to take his business elsewhere.

At Robinson’s trial, several of the prostitutes other than Helen, with whom he had had relationships, painted an ugly picture of a libertine youth making the rounds of the local brothels, including having an affair with a seventeen-year-old girl. One of the prostitutes who knew him testified that, “F. Rivers told her if any women exposed him he would blow out her brains” [Cohen 267]. Such testimony is particularly stunning considering Jewett’s fate, and it serves to highlight the nature of the letters Robinson wrote throughout the fall of 1835. Here Robinson refers to his awful treatment of Jewett, his own ill-temper, and sense of unbalance. He recognizes that he is being bad to her, but cannot control himself.

Through the winter of 1835-36, the two lovers were locked in a disturbed battle of intense emotions and psychological manipulation. Jewett went farther than she had ever gone with respect to her other clients, and clearly her relationship with Robinson was spiraling upward in intensity. They wrote intricate and fiery letters to each other, engaging in spasms of jealousy and genuine hurt. To read the letters in chronological order is to witness a deteriorating condition that Helen Jewett, a very skilled and successful prostitute, seems no longer to be able to control.

V. The Murder and Trial

During the cold opening months of 1836, Jewett and Robinson continued documenting their jealous rages and their desperate longing to fix a relationship that was perhaps beyond repair. There were times where they seemed to be separated, and Robinson frequently patronized other prostitutes; and there were times when the two of them were involved in some sort of intrigue that involved personages with names like Gilbert and Cashier, who shift below the surface of history forever out of our sight.

It was only a few weeks before her murder that Jewett went to work at Rosina Townsend’s brothel at 41 Thomas Street. In the final days, it is clear that the two were breaking up for good, and Jewett requested that her letters to him be returned (which he seemed to honor). However, a miniature portrait of him that he had given her to wear about her neck, which had been seen in her possession before his visit, had vanished from the crime scene. This portrait was found later at Robinson’s boarding house. Further, although Rosina Townsend saw Robinson’s bald spot and recognized him, by the time of the trial Robinson had shaved his head and was wearing a wig.

However, the rest of the circumstantial evidence against Robinson was overwhelming. His presence at the brothel, identified by several women, combined with the difficulty of anyone else having gained access to Jewett’s room due to the security measures of the house, made it unlikely that anyone but Robinson had been with her before her murder. Further, the black cloak discovered at the scene was identified by one of Robinson’s roommates as having belonged to him. The hatchet that had been found in the backyard, its blood washed off by the late-night rain, had been stolen from Hoxie’s store where Robinson worked. In addition, a white string tassel tied to the hatchet had been found to be broken off the fringe of the cloak. As for motive, Robinson’s diary, which had been taken from his boarding house and subsequently published, along with the sordid portrait of his character that emerged from it, presented such difficulties that any legal defense team would find it troublesome evidence.

In the weeks leading up to his trial, a large New York City contingent of sporting boys and dandies publicly came to Robinson’s defense. These supporters engaged in vocal protests in the streets and printed pamphlets emphasizing the circumstantial nature of the evidence against Robinson. They even adopted his foppish manner of dress, including the floppy silk hat he wore, which quickly became popularized as “Frank River caps” [Gilfoyle 98]. When a crowd of fifteen hundred people responded to a meeting of the Men’s Moral Reformers at Chatham Street Chapel, many of them were Rivers-supporting hooligans who disrupted the somber proceedings by pelting the stage with garbage and breaking the stage lamps, thereby inciting a riot.

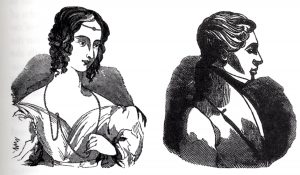

Lithographs of both the accused and the victim were widely distributed. The likeness of Robinson, cherubic and wide-eyed, beaming a boyish innocence, stood in stark contrast to the ugly picture that had emerged from his diary and letters. Jewett’s lithographs portrayed her in her famous green silk dress, heavily flounced and ribboned, carrying a parasol, handkerchief and letter; she was presumably on her way to a post office to mail a letter to one of her clients, perhaps Robinson himself. These lithographs sold like hot cakes, turning the two into overnight celebrities.

The trial opened on Thursday, 2 June 1836, on the second floor of City Hall, with Judge Ogden Edwards, a descendant of Puritan Jonathan Edwards, presiding. An estimated six thousand people surged around the building trying to gain entry to the spectacle, including, as was expected, a large contingent of Rivers-style sporting boys. Their presence in the court caused much disruption, and added a strange atmosphere when the testimonies of several prostitutes provoked murmurs and giggles from those who recognized the women from the various brothels that they had frequented.

The case for the prosecution emphasized the circumstantial evidence, including Robinson’s access to Hoxie’s hatchet and his ownership of the tasseled cloak. The defense attempted to build a case for a conspiracy designed to frame Robinson, focusing particularly upon the fact that the hatchet was found outdoors in the morning, hours after the murder, and easily could have been planted by one of the prostitutes. A roar of applause ripped through the courtroom as Rosina Townsend admitted that more than one client used the name Frank Rivers, and more than a few of the witnesses for the prosecution were pushed by the defense attorneys to admit their own sympathetic ties to the world of prostitution. Much was made out of the casual manner in which unknown men, also at the brothel that night, had quickly vanished from the scene without being questioned or even having their names recorded. One of the biggest blows to the prosecution was its failure to get Robinson’s letters admitted into evidence, due to the inability to positively identify his handwriting (Joseph Hoxie, Robinson’s boss, who certainly would have known the boy’s script, failed to give a positive identification of it, thus adding weight to the defense’s position that the letters should not be admitted).

One of the biggest surprises of the proceedings was the examination of Frederick W. Gourgons, a clerk in a Broadway apothecary shop, who testified that Richard P. Robinson had been in his shop sometime in early April, before the murder. Robinson was inquiring if he could buy arsenic, a request that Gourgons refused. This implied that Robinson, before settling on a hatchet as the means to dispatch Jewett, had tried to poison her first. Gourgons’ testimony, frustratingly enough, was inadmissible into evidence because arsenic was not the specific murder weapon mentioned in the indictment, and the day and hour of the visit to the apothecary did not match the specifics of the actual murder. One can only speculate how the case would have turned out if Gourgons’ testimony had been ruled admissible by the judge.

The defense also launched a surprise witness, the owner of a downtown grocery, who claimed that during part of the evening Richard P. Robinson was in his store, sitting on a barrel and smoking one of twenty-five cigars that he had purchased that evening. It did not help the prosecution that the owner was a friend of more than one juror in the jury box. In fact, as the case for the defense unfolded, there was a distinct feeling that Robinson’s greatest advantage was the camaraderie in the sporting life that he shared with many in the male-dominated proceedings.

Robinson was well-heeled and connected, from a prominent Connecticut family (the brother of the presiding judge was Governor of Connecticut at the time), and that was worth more to the jury than the testimony of prostitutes, madams, and common watchmen. Time after time, the reliability of prosecution witnesses was called in question. It was suggested that Rosina Townsend ignited the bed herself in order to collect on insurance, and that Robinson had brought Hoxie’s hatchet to the brothel (much in the same way women today would carry a can of mace), and left it there only to be used by Jewett’s murderer after Robinson’s departure. The barrage of doubt, and suspicion of all the circumstantial evidence, led to a verdict of Not Guilty on the fifth day of trial.

VI. Aftermath

No sooner had the trial ended, and Richard P. Robinson released back into private life, than an outcry emerged from the press and public that a great miscarriage of justice had been effected. There was even a demand for Judge Hoffman’s resignation. The appellation of “poor boy,” in which Robinson had cloaked himself during the trial, quickly evaporated when a twenty-year-old by the name of William Gray was arrested for theft, and had walked into a courtroom with more than a dozen letters written to him by Robinson. Indeed, Gray had been a boarding house roommate of Robinson’s, and had lent him the cloak that had been found at the scene of Jewett’s murder. Gray’s handing over the letters to the court may have constituted a plea bargain of sorts (an unsuccessful one, however: Gray was sentenced to Sing Sing).

Yet the letters produced by Gray clearly showed another face of Robinson, a sporting boy unashamedly talking to one of his own, engaging in a shared misogynistic and narcissistic vocabulary. Robinson reveals to Gray, who was engaged to be married, that he had indeed had sex with his fiancé, and would gladly do it again once they were married if it would help Gray secure a divorce on grounds of adultery. “She will not be the first married woman, who has felt my persuasive powers,” Robinson proclaims, after announcing that he has performed this service for other men before [Cohen 376]. He also boasts of his sexual conquests in New York, and threatens a servant girl with abuse if she testifies against him. The swagger, hostility, and the perception of a monstrous ego that emerged from Robinson’s letters to Gray, added fuel to the fire of controversy that dogged Robinson until the end of his life.

In July, an anonymous clerk friend of Robinson’s published a pamphlet called “Robinson Down Stream: Containing Conversations with the GREAT UNHUNG” in which Robinson, ever the sporting boy, sneered once more at the world and all its vanities: “I have nothing more to hope from the patronage of this hypocritical world,” Robinson announced. “I have no desire to flatter it. Mankind! I love ye not . . . I know your disguise; I have worn it—I know your arts; I have practiced them—I know the trickery of the stage; I have myself been behind the curtains—examined the scenes, scrutinized the tinseled wardrobes—sneered at the elements of a thunderstorm, and convivialized in the green room. I can unmask one half of New York and uncloak the other.” Besides revealing all the dramatic flourishes that he learned from the theater, he also shows his outrageous narcissism: “Half the women in New York were in love with me,” he announced when asked if Helen Jewett really had feelings for him. “I can go back to Gotham and marry an heiress” [Cohen 382, 383].

Yet, instead of returning to New York to marry an heiress, Robinson took flight on a steamboat and headed down to Texas to enlist in service in the war against Mexico. Not suitable as army material (he was mysteriously discharged from the First Regiment of the Texas Army), Robinson withdrew to Nacogdoches, a frontier town in East Texas. He adopted the name of R. Parmelee (his mother’s maiden name), and became the owner of a billiard hall and saloon. Exploiting the hard-earned skills that he had gained in New York, Robinson-Parmelee also became the clerk of the County Court, got married, and invested in real estate. In time, he even owned twenty slaves, and was one of the ten wealthiest men in Nacogdoches. He had prospered into a hard Texas aristocrat in a place that was wild enough for his misogynist and egomaniacal temperament.

There is evidence that some of his fellow Texans knew of his true identity, but for the most part he evaded any real scandal. While dime novels and pamphlets about the murder of Helen Jewett continued to be published during the 1840s, Robinson enjoyed his wealth and property. In 1855, while traveling on the Ohio River via steamboat, he contracted yellow fever and had to be brought ashore in Louisville. An elderly black woman who attended him at the end claimed that in his last moments Robinson ranted feverishly about Helen Jewett, calling her his wife. While this dramatic flourish is quite compelling, it cannot be proven, and Richard P. Robinson passed into eternity, enigmatic and unhung.

As for Helen Jewett, born Dorcas Doyen, she was buried in the churchyard of St. John’s Episcopal Church in what is now the neighborhood known as the West Village. Sadly enough, medical students from the College of Physicians and Surgeons dug up her grave just four short nights after her burial, dissected her and boiled her down to her skeleton. Her physical body, once an habitation of life, a source of income, and an object of desire for lustful New York City youths, mutilated and scorched and brutally murdered, may have found its final resting place in the collection of Dr. Valentine Mott, “the foremost snatcher of his day,” labeled as Item 714, a “lacerated cerebellum.” In the 1860s, a fire destroyed Dr. Mott’s gruesome collection, and, if this was she, Dorcas’ remains passed into eternity. The closest we can now come to a final resting place for Dorcas is the James J. Walker Park in New York City’s West Village, not too far from the brothel where she died. Under its asphalt and park benches is the soil where she lay for four days before her exhumation [Cohen 463].

As Helen Jewett, she continued to make frequent appearances in decades to come in pamphlets, in best-selling lithographs, and in the pages of dime store novels. Even a depiction of her murder was displayed in a Boston wax museum, along with the black-cloaked, hatchet-wielding Robinson; she was placed just a few exhibits away from a recreation of the murder of Sarah Cornell, a Fall River, Massachusetts, mill girl who was murdered in 1832. Cornell’s alleged killer, the Reverend Ephraim Avery, also escaped the gallows and similarly lived out the rest of his life under an assumed name, haunted by his past.

There is a sadness to the story of Richard P. Robinson and Dorcas Doyen. If not for one brief evening of homicidal rage, their sexual involvement and emotional tragedy may have disappeared into the secret flow of history as a passing fancy, enacted by a hot-blooded young man and a professional prostitute that he had hired for his pleasure, nothing more and nothing less. Eventually, Robinson would have moved on to his professional career, leaving behind his youthful foray into the world of whores. Dorcas, however, would have been trapped in that fallen world, incapable of any advancement, beyond the hope of marriage, and destined to either become a madam or to seek support from an on-going parade of lonely men who chose to rent out some little intimacy in the closed bedroom of a brothel.

“And turning to the body he said, “Dorcas, arise.” And she opened her eyes and, seeing Peter, she sat up. Then Peter gave her his hand and raised her up and calling the saints and the widows, he gave her back to them alive.” Acts 9:40-41

Works Cited:

Cohen, Patricia Cline. The Murder of Helen Jewett. New York: Vintage Book, 1998.

Gilfoyle, Timothy J. City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution, and the Commercialization of Sex, 1790-1920. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1992.