by Richard Behrens

First published in August/September, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

“The price of liberty is good behavior.” Milton Rosenua, Preventative Medicine and Hygiene, 1935.

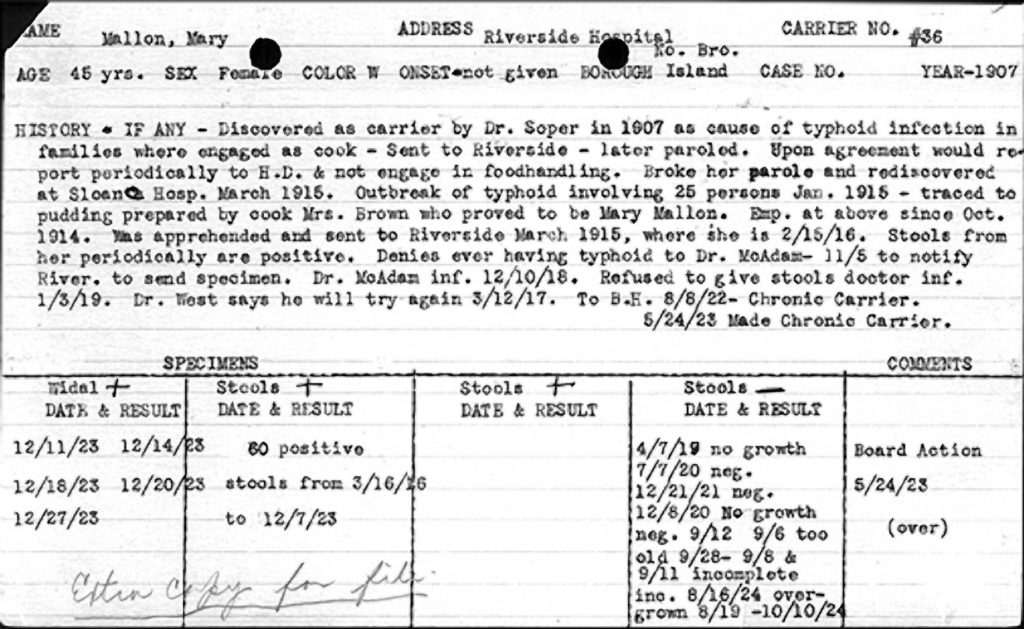

While there has always been debate as to whether Lizzie Borden murdered her parents, there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that Mary Mallon, popularly known as Typhoid Mary, for ten years, between 1900 and 1915, transmitted the deadly disease known as Typhoid to forty-seven distinct individuals, causing the death of three.

Borden and Mallon came from radically different socioeconomic backgrounds—Lizzie was the pampered daughter of a prominent businessman while Mary was an Irish immigrant who labored as a cook—but both were accused of killing people and both spent the rest of their lives languishing in solitary prisons. True, Lizzie’s prison was a large Victorian home in Fall River’s wealthier neighborhood surrounded by a cordon of servants, and Mary Mallon’s was a one room shack on a medical quarantine island with only a nurse who sampled her stool for contagion to keep her company, but both outcasts suffered from social stigmas that kept them isolated and painfully alone.

One can only suspect that if the two could have met and traded notes, they would have understood each other as no one else of their time could. Lizzie the Hatchet Killer and Mary the Human Pandemic, forced by the cruel stereotyping of history into their perceived roles as killers, remained unrepentant to their dying days.

Off the north shore of Queens, NY, just beyond Bowery Bay, sits the landmass of Riker’s Island where the Department of Corrections maintains a notorious prison facility for those who have committed crimes against society. But off the northwestern tip of this island is a smaller landmass facing the Bronx known as North Brother Island where the abandoned ruins of a large hospital and other health facilities tell the story of a very different kind of prison. Between the years 1907 and 1938, a solitary woman was there incarcerated, almost one third of her life span. She committed no crime and had been condemned by no court of law, but here Mary Mallon a.k.a. Typhoid Mary was kept in medical quarantine against her will for almost three decades.

The name Typhoid Mary has become a part of our culture. To say that someone is a Typhoid Mary is to describe them as spreading disease, causing those about them to die as they themselves move about unharmed. For this reason it shocks many people to hear that Mary Mallon was only responsible for three deaths and those were certainly unintentional. Mary had the misfortune to be the first healthy carrier of the disease verified by the New York City Department of Health. Her sequestration one hundred years ago and her subsequent vilification by the press is a controversial case study of how far we would go to protect ourselves from disease, even at the price of civil liberties.

Mary Mallon was born in 1869 in County Tyrone, Ireland and immigrated to America as a young woman, alone and determined to survive, like so many other Irish girls of her day, as a domestic cook. By all accounts, her cooking career was a success: she worked for many wealthy families on Long Island and in Manhattan. Between the summer of 1900 and March 1907, she worked in Mamaroneck, Sands Point, Tuxedo Park, Oyster Bay, and on Park Avenue. However, at all these locations, members of the family and/or the domestic staff came down with typhoid, twenty two cases altogether. One person died of the contagion.

It is easy to believe that Mary had no awareness that she was spreading the disease. In 19th Century America, typhoid was a tragically common occurrence and it is hard for a modern reader to appreciate just how widespread the disease was. Statistically, there was little reason to think that her presence in so many infected households was unusual. Of the several thousand people who contracted typhoid in New York State in 1906, there were more than 600 fatalities and only one of them happened in a household where Mary worked. To her, she could not possibly be the carrier because she herself exhibited no symptoms of the disease. She had even stuck around to nurse the sick and quit soon after in fear she would catch typhoid.

At the beginning of the last century, it had become a primary directive of many health departments in the United States to fight the disease, largely through the improvement of living conditions, cleaner water supplies, better sanitation and the reduction of physical filth. Moreover, the emerging science of bacteriology focused on attacking the bacilli themselves, but of course, to attack them, these invisible enemies first had to be found. The thought that they could be lurking in a healthy individual who worked in impeccably clean conditions was pushing the boundaries of what we knew about disease propagation at the time. In 1907, science had not yet proven that such a thing as a healthy carrier actually existed and there were no laws on the books to determine how to handle such an individual should they be discovered.

George Soper, who had made his reputation as a sanitary engineer specializing in epidemics, was hired by Mr. and Mrs. George Thompson to investigate the outbreak of the disease at their Oyster Bay mansion where their summer tenants, the Warren family, resided. Soper was determined to make a name for himself by capturing America’s first scientifically recognized healthy carrier. After learning that Mary Mallon had worked as a cook in Warren’s household in the summer of 1906 and left shortly after the outbreak, Soper traced her employment history and found the large number of typhoid cases in her wake. This led him to pay a visit to Mary as she worked in the kitchen of the Bowen family on Park Avenue.

Soper approached Mallon with a passionate argument that she may be causing the infections in her clients through her cooking and her failure to clean her hands properly after bowel movements. He requested that she supply stool and urine samples to determine if she was indeed a carrier. Mary responded by pulling out a roasting fork and chasing him from the premises. Determined to put his name into the annals of bacteriological history, Soper buddied up to Mary’s working class boyfriend, confronting her for a second time in her own apartment on Third Avenue and Thirty Third Street. She responded with an equally violent reaction and Soper beat a hasty retreat.

Feeling that this was indeed a job that required a woman’s touch, the Department of Health sent in S. Josephine Baker, a city medical inspector, with an ambulance and five police officers. When they confronted Mary at her place of employment, she fled and hid in a staircase closet for over three hours as Baker and the policemen searched several houses. When discovered, she put up such a fight that in the wagon, while she howled obscenities and hostile imprecations at her captors, Baker had to physically sit on her to keep her from escaping. Mallon was removed to an isolation cabin on North Brother Island where she was to remain, with the exception of a few brief years of freedom (1910 to 1915), for the rest of her life.

gives a capsule history of her capture and quarantine. From PBS.org.

Almost from the moment of Mary Mallon’s capture, serious legal and ethical issues had been raised about her arrest and captivity. While Soper and Baker gained some notoriety for identifying and isolating the typhoid carrier, Mallon herself was deprived of her freedom. The charter for the New York City health department did mandate that it should protect the public health of the city by removing “or cause to be removed to [a] proper place to be by [the Board] designated, any person sick with any contagious, pestilential or infectious disease…” [New York City Department of Health Charter Section 1170]. The problem with this directive is that it was written before the discovery of healthy carriers. It is one thing to deprive someone of his or her liberty because they are burning up with a 105-degree fever from an infectious disease. It is quite another matter to incarcerate a perfectly healthy individual.

by the authorities in 1907 for being a carrier of typhoid fever. From PBS.org.

However, there was no small lack of evidence. The health department did take several stool samples a week from Mary in the beginning. Of the 163 samples taken during the period from 1907 to 1909, 120 tested positive for the typhoid bacteria, and 43 tested negative. When her case did get reviewed by a court of law in 1909, Mary produced test results that she had done with an independent lab, all of which tested negative. However, it was believed that the longer amount of time between the excretion of the samples and the delivery of them to the lab gave the typhoid time to degrade. Another possibility is that Mary went through periods where the bacilli were not active as can be seen in the 43 negative tests done by the health department.

There was no doubt in anyone’s mind, excepting perhaps Mary’s own and her lawyer’s, that she was a perfectly healthy woman who carried the typhoid bacilli about in her gall bladder and had spread the disease to others through a combination of food preparation and poor sanitary habits. Although a judge ruled against her release in 1909 in a hearing where bacteriology itself seemed to be on trial, the Hearst newspapers unexpectedly drummed up public sympathy.

In a lengthy article in the June 20, 1909 edition of the New York American, Hearst seized upon the name “Typhoid Mary,” which had been used in a medical journal to mask Mallon’s identity (in a modern scientific paper she would be called Mary M.), and published a drawing of a domestic cook tossing small human skulls into a frying pan as if they were eggs of death. It declared her “most harmless and yet the most dangerous woman in America” and did drum up public outrage against her incarceration on North Brother Island. Other newspapers such as the New York Herald and the Times followed suit in casting her in a sympathetic light, although they all milked the strongly evocative term “Typhoid Mary.”

What happened to turn the tide of popular opinion against her was what she did when she was finally released from the island in 1910 due to the sympathies of a new health commissioner. She unashamedly violated the conditions of her release, which was to remain in touch with the Board of Health and to refrain from making her living as a cook. In 1915, after being off the radar for several years, she reemerged at New York’s Sloane Maternity Hospital where twenty-five individuals came down with typhoid fever, two of them eventually dying from their illness. Sure enough, Mary was found working under an assumed name and she was unceremoniously dragged by the Board of Health back to North Brother Island, this time for good.

Because of her deliberate disregard for public health precautions and her continual refusal to admit the danger she posed to those around her, public sympathy for her almost completely vanished. This time she had clearly spread the disease with full awareness of what she was doing, although she still claimed that she was perfectly healthy.

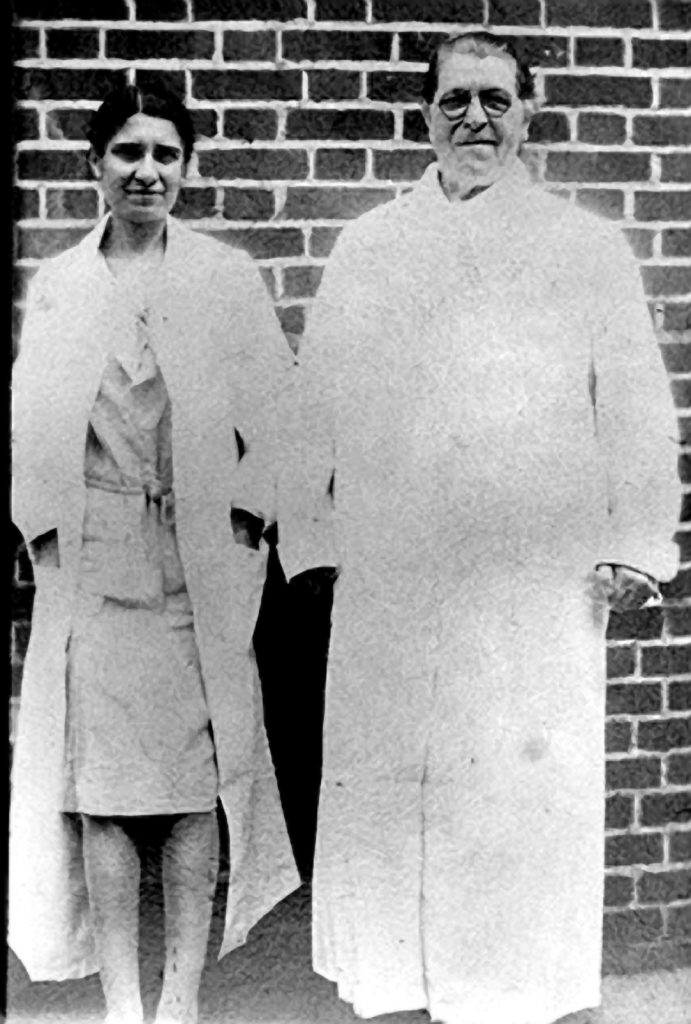

While Mary did grow accustomed to life on North Brother Island and became over the years less enraged over her predicament, she did continue to deny that she was a threat to anyone. She obtained a position working in the island’s hospital and there is evidence that she even took day trips into Long Island and Manhattan. The public soon forgot her, she grew old and sick, and then in 1938, after several years bed ridden from a debilitating stroke, she passed away. The last known photograph of her on the island shows a big beefy woman with a partially paralyzed face. She never gained back her full liberty and she never accepted the scientific evidence of her being a healthy carrier of typhoid.

The questions remain about how Mary Mallon, who was not the only healthy typhoid bacilli carrier in New York in 1907, became so notorious and well known, why her incarceration and treatment at the hands of the Department of Health was more severe than any of the other known healthy carriers, why she became an American icon for pathogenic hysteria. Some of the other carriers identified by the New York City Department of Health were responsible for more infections and more deaths than Mary Mallon; however, the other carriers played nice, agreeing to the restrictions of the officials, reporting to their case handlers on a regular basis, giving stool samples to track their condition over time, and agreeing to refrain from certain professions like food preparation. Mary disregarded all these directives, attacked officials with a weapon, and violently denied she was the cause of the suffering about her. By setting a stern example with Mary Mallon, the Department of Health had their Typhoid poster girl as a warning to other healthy carriers who may consider rebelling against them.

At the time, the growing concern over public health had reached a frenzied peak and was fueled by scientific discoveries over the bacteriological origin of diseases. For many decades, the understanding was that filthy living conditions bred disease, but the new thinking, sparked by the isolation of microorganisms in the bodies of the sick, actually stirred a debate over whether the approach to eliminating diseases was to enforce better sanitation and living conditions or to simply go after the microorganisms. While we now understand that disease is a collaboration between the two—filth helps to propagate the bacteria—in the early 1900s, many medical men and social reformers fanatically favored one approach to disease eradication over the other.

In 1907, science seemed to be winning the bacteriological battle on both fronts. With health organizations well funded in every state, sanitation programs and municipal strategies for cleanliness of water and living conditions were taming the deadly epidemics that were plaguing the country. The possibility of healthy carriers, people who were in fine bodily health but who carried the bacteria in their bodies and could spread it to those about them if they were not being mindful of their sanitary habits, was helping to sustain a paranoid fear much akin to the AIDS scare of the 1980s. Clearly for science to complete its victory, it would have to come up with a way of handling this fearsome source of contagion. Mary Mallon was one of the first widely publicized cases of a healthy carrier that scientific investigation had isolated. She stood as a symbol of science’s ability to seek and destroy disease wherever it was hiding, whether in spoiled food supplies, unhealthy drinking water, or Mary Mallon’s gall bladder. By isolating her, apprehending her, and forcing her into quarantine for the rest of her life, public health science was asserting its authority and its ability to defeat a deadly epidemic.

The severity by which her liberty and rights as a human being were denied was part of this triumph. Mary’s defiant stance against the Department of Health made her even better press and put her in alignment with the disease itself. Other healthy carriers played by the rules, taking care of themselves and adhering to strict guidelines in order to protect others from their own disease. They would use exclusive toilets and limit their employment opportunities that often put them under financial hardship. Mary refused to do any of this, and caused many infections as a result. She had to be restrained, against her own will, for the public good. No other healthy carrier made such a stink, and by refusing to cooperate with the Board of Health, she was deemed, in the view of many, to be no better ethically than the disease. To isolate and contain Typhoid Mary became synonymous with isolating and containing typhoid itself.

Like Lizzie Borden, there have been many novels, plays, and even an interpretative dance that were either based on or inspired by Mary Mallon’s tragic life. While in her day she was viewed through the lens of society’s desire to eliminate pandemics through the power of modern science, the creative arts generated from her story in the last few decades have largely focused on feminist issues, comparisons to the Reagan administration’s policies towards victims of AIDS, and larger existential issues. Barry Drogin and Peg Hill’s 1988 dance production Typhoid Mary has the Irish cook preparing a meal on stage that is subsequently fed to the audience, forcing them to confront their fear of being infected by the outsider.

Few people today know or remember the actual facts of Mary Mallon’s case, but everyone knows her nickname, even if they are surprised to hear that Typhoid Mary was a real person. She is buried in the Bronx, far from her Irish homeland but only a short distance from North Brother Island where she lived in isolation for three decades.

Satellite photography on the Internet gives a sad testament to the legacy of Typhoid Mary. At Wikimapia, you can examine the landmass of North Brother Island as it stands today, abandoned and overgrown with forest. At a higher magnification, you can see the roof of Riverside Hospital. The location of Mary’s isolation shack is completely covered with trees. Nothing remains but the name Typhoid Mary, one that she personally despised but which has been embraced by our collective cultural imagination.

Works Cited:

Bourdain, Anthony. Typhoid Mary: An Urban Historical. NY: Bloomsbury Press, 2001.

Leavitt, Judith Wlazer. Typhoid Mary: Captive To The Public’s Health. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996.