by Richard Behrens

First published in February/March, 2007, Volume 4, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Lizzie Borden spent much of her life as a wealthy woman, either living a life of leisure on Second Street with her prosperous father or ensconced on the Hill as Lizbeth of Maplecroft. However, for the first half of her upper middle class existence, she was a virtual prisoner of her father’s frugality, and during the later half she had too uncomfortable a social standing to really prosper and make a significant impact on her community (other than being a notorious patricide). Lizzie never quite became a great woman of her time. If not for the hatchet murders of 1892 she may never have made the history books. To her, someone like Hetty Green, the Witch of Wall Street, who was the most financially successful female in American History, must have seemed like an unrealized dream. But beyond the fact that they were American women who had some talent for managing their dead fathers’ money, these two Victorians were as different as night and day.

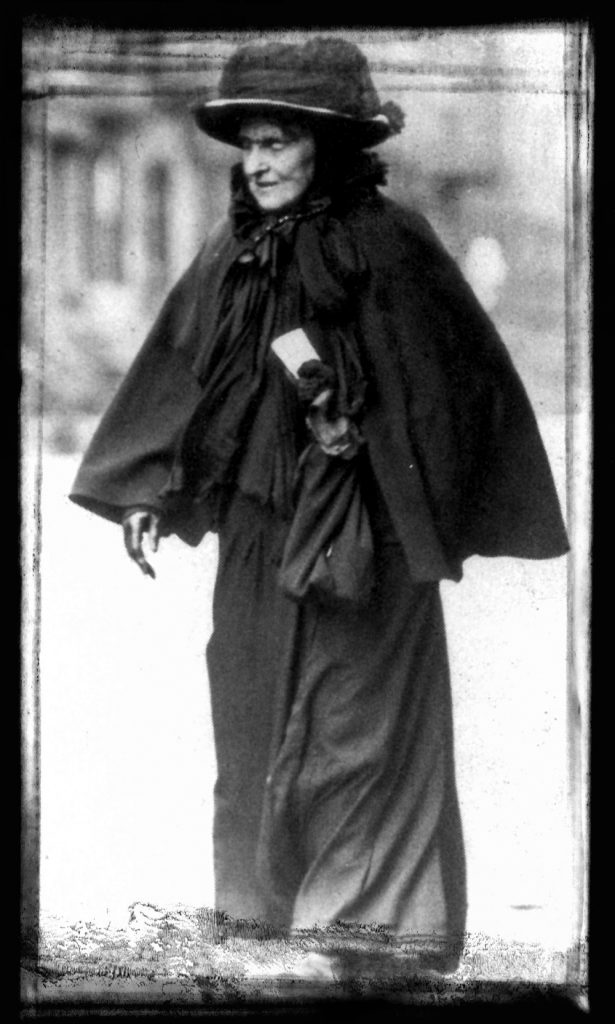

During the first decade of the 20th Century, the streets of lower Manhattan played host to an almost daily event that unnerved and bewildered many a pedestrian: Hetty Green was walking to work.

The eccentric millionaire and resident of Hoboken, New Jersey, infamous for her stinginess and unwillingness to spend a dollar on her own creature comforts, came across the Hudson River each morning on a New Jersey ferry, draped in a black dress that was literally falling apart from being worn continually without being washed, topped by a dark flowery hat that made her look like a ghost from another era. Now in her 70s, an advanced age that enhanced her wraith-like appearance, she was soon dubbed by New Yorkers the Witch of Wall Street.

Her destination was her offices in the financial district where she would spend her days surrounded by her stocks and bonds, reportedly eating oatmeal that she heated up on the radiator because she would not pay for proper food, controlling her wealth with a spectacular talent for success that awed even the most prosperous of her fellow financiers. Having taken an initial inheritance of $5.7 million and turned it into an astonishing $100 million by the time of her death, she made history as a woman who ran the bull on the market harder and longer than most investors of her day, and being a female in a male dominated world of power and wealth, just compounded the scope of her astonishing achievement.

Henrietta Howland Robinson was born in 1834 in New Bedford, Massachusetts, one of the most important cities in the history of American whaling. She came into the world less than five decades after New Bedford’s incorporation as a town in 1787 and thirteen years before it officially became a city. Its close proximity to Nantucket and its natural seaports made it an ideal capital for the American whaling industry. Many of the down-to-earth humble Quakers who inhabited the area became extremely wealthy due to the immense profits that were to be had from the butchering of the Leviathan. Indeed, Hetty’s family fortune came from investments in the whale industry.

Whale oil was, in its day, a crucial source of energy and light, making the industry that surrounded its production the 18th century equivalent of Consolidated Edison. But so great was the demand for the oil that the hunting fleets out of Nantucket and New Bedford dramatically altered the world’s whale population in just a few short decades. The hunters all but exhausted the fisheries in the North Atlantic, so great was the slaying, and they would often sail on voyages that lasted years, traveling as far as the Pacific Ocean. So compellingly exotic was the life of an American whaler that Herman Melville (who sailed out of New Bedford as a whale man) was to score a commercial bestseller with Moby Dick, a 700+ page description of every grueling aspect of whaling imaginable and which painted a vivid portrait of New Bedford in its opening scenes before heading out to the open ocean with Captain Ahab and his crew.

Hetty Green, whose father, Edward Mott Robinson, owned a whaling fleet, grew up amongst opulence that was no doubt sheltered away from the harsh realities of the seafaring life and the slaughter of the great mammals. Besides being pampered and privately schooled, her Quaker heritage enforced a humble austerity that may help explain some of her later life-style contradictions. Never possessed with any desire for ostentation or opulence, she was trained to value every penny of a dollar. From an early age she was reading financial reports out loud to her family and learning all she could about money management and investment. At the time of her father’s death in 1864 Hetty inherited $5.7 million dollars. One of the first signs of her eccentricities towards money was a lawsuit she initiated against her own aunt’s estate to prevent $2 million of her fortune to be donated to charity. She was suspected of forging a crucial document. She lost the case because the judge threw out the foundation of the civil suit. Hetty appealed, but then the parties compromised.

But at the time that Hetty inherited her money, the discovery of petroleum as an alternative source of energy had cast the whaling industry into its twilight years and Hetty felt compelled to reinvest all of her money in deprecated Civil War Bonds. During the war, the U.S. government had issued paper money or “greenbacks” which didn’t always have full-value, and they were considered, at the time, unstable as a long-term investment. But Hetty kept a cool and level head, navigating through the financial turmoil of the post-Civil War period as a highly successful investor.

As uncharacteristic as it may seem, Hetty had a husband and children. She married Edward Henry Green, a wealthy man himself, shortly after obtaining her inheritance, and attempted to separate the management of his fortune from her own. It had been rumored that Edward even signed a pre-nuptial renouncing all claim to her money but their marriage suffered eventually from financial stress. Hetty found out in 1885 that her financial house, John J. Cisco and Son, had secretly made deals with her husband, and when the house failed, she withdrew all her securities and deposited them in Chemical Bank. Further, she dropped her husband like he had been a bad investment, reconciling with him only near the end of his life where she nursed him during his last illness.

Hetty invested mostly in real estate and railroads. She was always quick to loan at reasonable rates, but never to borrow. In 1907, during a financial crisis, she gave New York City $1.1 million in exchange for revenue bonds. She used offices at the Seaboard National Bank in lower Manhattan but refused to pay rent, opting to take over random desks, surrounding them with her suitcases and financial papers which made her resemble a bizarre cross between J.P. Morgan and a bag lady.

Over the years the wild stories of her shabby existence ran rampant, so much so that biographers have difficulty weeding out what is fact from what is fantasy or mere exaggeration. It is true that she took the Hoboken Ferry to work each day, and rode on public streetcars, during an age when she could have owned her own private railroad. It is also a fact that she tried to save money on hospital bills, dressing shabbily when visiting doctors with her young son after he injured his leg. Over time, she tried treating it with home remedies, but it never fully healed. At the age of twenty, her son’s leg was finally amputated. In later life she resorted to a wheelchair because she didn’t want to pay the $150 to fix her hernia. Finally, she spent much of her last years drifting between small apartments in various cities, afraid of tax collectors and growing increasingly paranoid that people were after her money.

Over the years the wild stories of her shabby existence ran rampant, so much so that biographers have difficulty weeding out what is fact from what is fantasy or mere exaggeration. It is true that she took the Hoboken Ferry to work each day, and rode on public streetcars, during an age when she could have owned her own private railroad. It is also a fact that she tried to save money on hospital bills, dressing shabbily when visiting doctors with her young son after he injured his leg. Over time, she tried treating it with home remedies, but it never fully healed. At the age of twenty, her son’s leg was finally amputated. In later life she resorted to a wheelchair because she didn’t want to pay the $150 to fix her hernia. Finally, she spent much of her last years drifting between small apartments in various cities, afraid of tax collectors and growing increasingly paranoid that people were after her money.

But while history always paints a portrait of Hetty with an emphasis on her reclusive eccentricities and extreme parsimony, it is worth a moment to examine a few aspects of her financial strategies that in and of themselves offer her an esteemed place in the Wall Street Hall of Fame. According to the Museum of American Financial History, these strategies were very simple indeed: Hetty never borrowed but always lent, she never consumed her investment principal, and she shunned the short term risk in favor of long term stability. It is a mathematical fact that Hetty increased her wealth from under $10 million to $100 million over fifty some odd years, and according to the Financial Museum “this feat can be accomplished with an annual compound rate of interest of less than 9.5%” Clearly there was no magic involved in the growth of her colossal fortune other than a life-long stubbornness, an unusual ability to navigate through stock panics and a refusal to speculate. Paradoxically, part of her success was her inability to give in to greed.

What is most fascinating about Hetty Green, beyond the stories of her rotting clothing and radiator-cooked meals, is that she spanned a wide plank over two very different eras of American history. Her life started in a New England whaling community just about half a century after the American Revolution but ended in a very modern looking Manhattan which, by the time of her death, was filling rapidly with the technological marvels of the 20th Century—electricity, telephones, movie palaces and automobiles. While she always lived in the presence of wealth and only wanted for material comforts by her own choosing, she remained at heart a colonial working woman who brought to her Wall Street obsession a frontier mentality of fortitude and deep survival instincts. Her eccentricities may have been merely an extension of the ever-diligent sacrifice paid by her ancestors as they worked the land and spent years at a stretch hunting the whale, while the newly born America grew up about them.

Indeed Hetty Green was witness to American industry’s financial growth spurt that started with the colonial whaling fleets of the pre-industrial age to the giant banking houses and corporations of the modern world. In her youth, she learned well from the Captain Ahabs of New England with their austere Quaker ways, profound earthiness and steadfast vigilance on the seas as they waited for the spouting signs of their mighty sea beasts. As a grown women, she played hard with the tycoons of the Wall Street towers, besting them at their own game with her stern obsessive patience and fierce slow burning aggressiveness.

It can be argued that her controversial life style was a defense against the male dominated financial community that would have preferred their playing field be kept free of the female sex. Perhaps she chose not to partake of material self-indulgence in order to define herself as a down-to-earth pioneer who knew that every dollar earned through patience, labor and sacrifice was a gem dug harshly from the earth at a very dear price.

Perhaps if she had been more ordinary, less reclusive, or more connected to the fads of her generation, she wouldn’t have fared as well. It seemed to have been her deep alienation from the world and her stubborn refusal to nurture anything else in her life other than her fortune, which made her so unique a woman in American history.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: A brilliant fictional parody of Hetty Green can be found in Kurt Vonnegut’s 1979 novel Jailbird (Delacorte Press) in the character of Mary Kathleen O’Looney, a New York City bag lady who is in reality the CEO of the fictional RAMJAC Corporation.

Works Cited:

Actual Virtual Vermont Internet Magazine. “Hetty Green.” 21 January 2007. 27 January 2007 <http://www.virtualvermont.com/index.php?loc=http://www.virtualvermont.com/history/hgreen.html>.

Grinder, Dr. Brian and Dr. Dan Cooper. “Hetty Green: Legendary Wall Street Investor.” Museum of American Financial History. 2005. 27 January 2007 < http://www.financialhistory.org/fh/1996/55-1.htm>.

Lewis, Arthur H. The Day They Shook the Plum Tree. NY Harcourt, Brace & World, 1963.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex. NY: Viking Penguin, 2001.

Sparkes, Boyden and Samuel T. Moore. The Witch of Wall Street. Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1935.