by Richard Behrens

First published in November/December, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 4, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

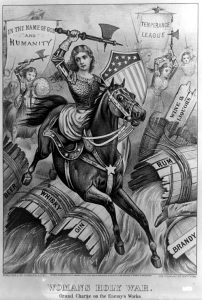

Carrie Amelia Moore Nation was a flamboyant, theatrical and completely outrageous woman, who was a self-described “bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at what he doesn’t like.” At nearly 6 feet tall, she cut an imposing figure. Her intimidating presence was not eased any by the hatchets that she often wielded, when, in the name of Christian temperance, she entered bars and saloons to chop up furniture and bottles to destroy the drunkard’s watering hole at its source. She often described her victims as “rum-soaked, whiskey-swilled, Saturn-faced rummies” and led her attacks with the rallying cry of “Smash, ladies, Smash!”

Carrie Amelia Moore Nation was a flamboyant, theatrical and completely outrageous woman, who was a self-described “bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at what he doesn’t like.” At nearly 6 feet tall, she cut an imposing figure. Her intimidating presence was not eased any by the hatchets that she often wielded, when, in the name of Christian temperance, she entered bars and saloons to chop up furniture and bottles to destroy the drunkard’s watering hole at its source. She often described her victims as “rum-soaked, whiskey-swilled, Saturn-faced rummies” and led her attacks with the rallying cry of “Smash, ladies, Smash!”

Although not the only famous teetotaler of her generation (Susan B. Anthony and George Bernard Shaw were known for their temperance work as well) she was certainly the brassiest and the most feared. Arrested over 30 times between 1900 and 1910, she also went on whirlwind lecture tours, published her own newspaper (The Smasher’s Mail) and provided mail order autographed postcards of herself that still pop up on eBay from time to time. From all over the country her supporters would send her hatchets to show their approval of her Elliot Ness-like tactics in fighting the evils of alcohol. She even had her name, Carry A. Nation, officially trademarked to exploit its fearful symbolism.

Carrie Nation was born in 1846 in Kentucky and later moved to Missouri where she married a hopeless drunk who died after two years of marriage. Remarried to David Nation, a lawyer and minister, and moving to Medicine Lodge, Kansas, Carrie got increasingly involved with the state temperance movement, at first advocating peaceful protest to close down saloons and drive out the drunks.

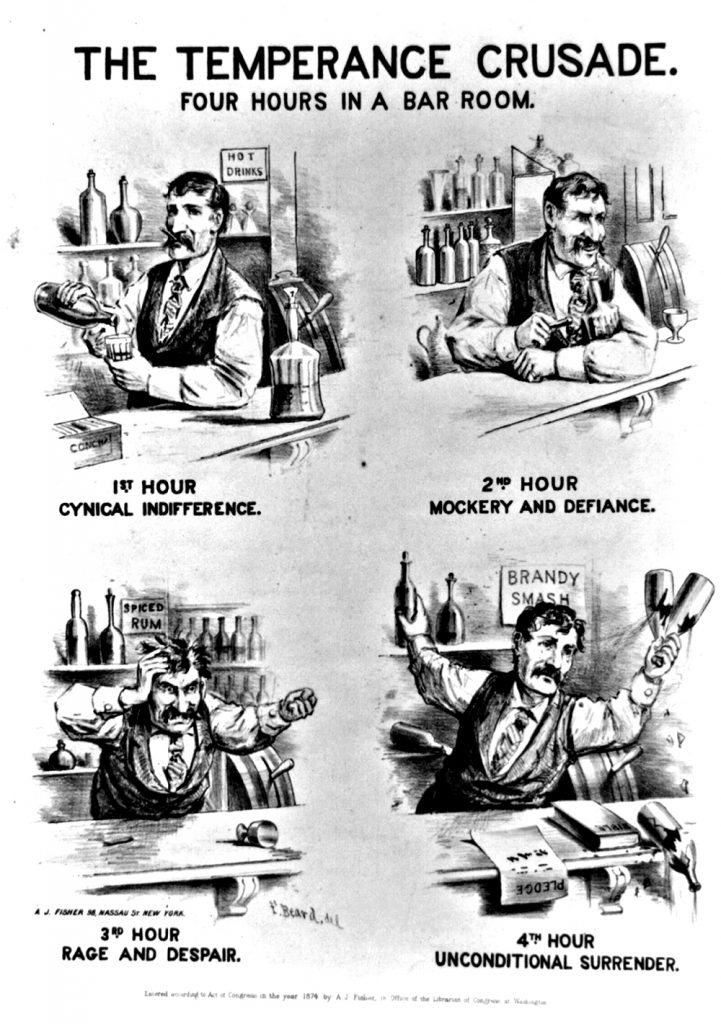

Kansas has been one of the first American states to prohibit alcohol by constitutional amendment in 1880, but it took a while for the saloons to close, and Carrie Nation and the Kansas State Temperance Union certainly did their part to hurry along the process. But political corruption, a sagging US economy, and a less than enthusiastic law enforcement community allowed the dens of iniquity to continue to ply their trade.

Sometime in the spring of 1900, Carrie seemed to have re-evaluated the efficacy of non-violence. Apparently, standing outside a saloon singing hymns and reciting Biblical temperance poetry wasn’t cutting her mustard. So, fed up with the hypocrisy and the on-going spread of alcoholism, Carrie, at 54 years of age, tucked up a stash of bricks and bats into her buggy and drove out of Medicine Lodge to go on an infamous tour of violence through several towns and cities.

Urged on by the voice in her head telling her that He would stand beside her in any action she felt compelled to take against vice, she burned through Kiowa, Wichita and Topeka, landing several stints in jail of several weeks each. She was beaten by saloon keepers’ wives, heckled by irate citizens, and criticized widely, even by the Kansas State Temperance Union who disapproved of her extreme tactics in advancing their own cause.

Eventually, however, her charisma and ability to draw a large approving crowd, not to mention stirring new membership for the KSTU, won over the public, and before the end of 1901, Carrie had organized groups of Home Defenders, all armed with their pokers and bats and hatchets. At their approach, no keg, cask or stein was safe. Chairs, stools and billiard tables were chopped into splinters. Expensive glass windows were shattered. Slot machines were broken. Befuddled drunks were tossed to the gutter. According to contemporary accounts, few put up any significant resistance and Carrie’s popularity grew exponentially.

The Home Defender’s attacks on the rum halls of Topeka led to a confrontation with the state senate after Carrie targeted Topeka’s Senate Saloon, an establishment frequented by legislators. “You refused me the vote,” Carrie told them, “and I had to use a rock!” The senate eventually passed significant legislation that did not completely wipe out alcohol from the state of Kansas, but established a stronger prohibition than the weakly enforced one that had driven Carrie Nation to violence.

After her triumph in Kansas, Carrie went on to give lecture tours and to publish a newsletter. She ran a lucrative mail order business that sold autographed postcards and miniature hatchets. Her writings were often filled with religious justification for her deeds, but the fad that she had created was non-sectarian and appealed to a wide variety of reformers and women’s rights activists. Eventually Carrie hired a talent agent and went on a theatrical tour, smashing barrels on stage and singing her temperance songs to enthusiastic audiences who howled for more.

After her triumph in Kansas, Carrie went on to give lecture tours and to publish a newsletter. She ran a lucrative mail order business that sold autographed postcards and miniature hatchets. Her writings were often filled with religious justification for her deeds, but the fad that she had created was non-sectarian and appealed to a wide variety of reformers and women’s rights activists. Eventually Carrie hired a talent agent and went on a theatrical tour, smashing barrels on stage and singing her temperance songs to enthusiastic audiences who howled for more.

Her acts of violence against saloons became known as “hatchetations.” Prizefighter John L. Sullivan, “the Boston Strong Boy,” reportedly broke down out of fear when Carrie Nation entered his New York saloon and he converted to a staunch prohibitionist. Such stuff was the material of legends.

Carrie Nation, despite her over commercialized theatrics, did contribute much to the wider movement in which she is situated in history. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, of which Lizzie Borden was once a member, started in Fredonia, NY in the early 1870s. It not only addressed issues surrounding alcoholism in society, but also prostitution, recreational drugs, domestic violence, prison reform, public health and eventually woman’s voting rights. As early as 1875, the WCTU tried to raise public awareness of the dangers of tobacco, quite a large leap for the time. Their particular Christian bent, unfortunately, forbade Jewish or African American women from joining their ranks, but despite that gross lapse in political correctness, they indirectly helped all women in this country empower themselves and address serious substance abuse and health concerns that plagued a society just emerging from a frontier mentality and a male-driven industrial expansion.

The movement spread quickly all over the world and although Carrie Nation represented an extreme measure within its larger tactics, she certainly was acting in accord with its principles. Carrie was very much a woman of her time and place. Medicine Lodge, Kansas was a very different type of society than Fredonia, NY, and the genteel women of the gilded age who marched in the streets of New York were not dealing with the wild frontier drunkard of the western states. Moreover, as we have seen, Kansas was a state struggling with its own prohibition legislation, and awareness of the corruption and legal indifference to the state’s own laws provoked people like Carrie into extreme measures. After all, Carrie was merely demanding that the Kansas State Government enforce their own neglected laws. From her perspective, she was not only doing the work of the Lord, but adhering to her own Constitution.

The movement spread quickly all over the world and although Carrie Nation represented an extreme measure within its larger tactics, she certainly was acting in accord with its principles. Carrie was very much a woman of her time and place. Medicine Lodge, Kansas was a very different type of society than Fredonia, NY, and the genteel women of the gilded age who marched in the streets of New York were not dealing with the wild frontier drunkard of the western states. Moreover, as we have seen, Kansas was a state struggling with its own prohibition legislation, and awareness of the corruption and legal indifference to the state’s own laws provoked people like Carrie into extreme measures. After all, Carrie was merely demanding that the Kansas State Government enforce their own neglected laws. From her perspective, she was not only doing the work of the Lord, but adhering to her own Constitution.

As she advanced in years, her overly ostentatious behavior became more relevant on the national stage as women’s passions for their own suffrage heated to a violent broil and the modern woman’s movement swept through the sweatshops and inner cities of the country. Even before she died in 1911, women were taking more daring political and social action, like Jewish Anarchist Emma Goldman declaring to a group of workers in Union Square, “Ask for work; If they do not give you work ask for bread; If they do not give you work or bread then take bread” and getting arrested for her incendiary words.

Carrie Nation was indeed a fiery spark in American history. Her bizarre presence was also a curious prelude to the modern age of celebrity where people are famous for being famous. She rose to notoriety almost overnight, and very shortly after she smashed up her first saloon in Kiowa, her image was marketed widely throughout the States. One could easily imagine her appearing on the David Letterman show or staging a stunt in the middle of Times Square a la David Blaine. In her time, in fact, popular songs were written about her with lyrics such as:

When time shall build the marble guild,

That marks man’s reformation,

Its arch of fame shall bear the name

Of dauntless Carrie Nation.

Her righteous scorn of rum and wrong—

May all creation catch it,

And join the “Woman’s World Crusade,”

Armed with “our nation’s” hatchet.

Minna Irving in Leslie’s Weekly

Although never a profound intellectual (she had more in common with Calamity Jane and Annie Oakley than Susan B. Anthony or Emma Goldman), Carrie Nation definitely stirred the American collective imagination, giving it a new icon to emblazon in its hallowed history. And while this sassy frontier woman from Kentucky who wielded a hatchet in the name of her Lord never quite knew the genteel upper middle class quietude of Lizzie Borden’s life, something tells me the two of them would have found much to talk about.

Although never a profound intellectual (she had more in common with Calamity Jane and Annie Oakley than Susan B. Anthony or Emma Goldman), Carrie Nation definitely stirred the American collective imagination, giving it a new icon to emblazon in its hallowed history. And while this sassy frontier woman from Kentucky who wielded a hatchet in the name of her Lord never quite knew the genteel upper middle class quietude of Lizzie Borden’s life, something tells me the two of them would have found much to talk about.

And by the way, as far as we know, Carrie Nation never involved herself with animal rescue, ironing handkerchiefs or teaching Chinese school children, but it would have been wonderfully coincidental if she had.

Works Cited:

“Carrie Amelia Nation.” Kansas State Historical Society. 2 November 2006 <http://www.kshs.org/people/nation_carry.htm>.

“Crusades.” Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. 2 November 2006 <http://www.wctu.org/crusades.html>.

“Early History.” Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. 2 November 2006 <http://www.wctu.org/earlyhistory.html>.

Nation, Carrie. The Use and Need of the Life of Carry A. Nation by Carry Amelia Nation. 10 October 1998. Project Guttenberg. 2 November 2006 <http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/1485>.