by Tina-Kate Rouse

First published in February/March, 2005, Volume 2, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

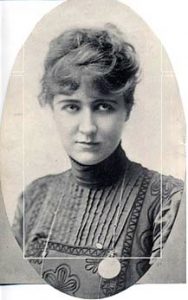

The first line spoken onstage by nineteen year old Gertrude Lamson was: “Narren Beaudet, you are dismissed from St. Lazarre.” The play was called Sara, and it was produced at the Alcazar Theatre in San Francisco by veteran thespian McKee Rankin. Due to Lamson’s extraordinary height, Rankin had cast her as one of two nuns. Even from such humble beginnings, she received good reviews. October 17, 1893, a critic for the San Francisco Evening Bulletin wrote, “. . . a winning Miss Gertrude Lamson as ‘Sister Elsie’ had a capital scene in the prison which she carried very well.”

Gertrude Lamson had an elder sister named Lillian, who preceded her own entrance on stage by three years. Their father was born in Lowell, Massachusetts and had journeyed to California in search of gold in 1849. Their mother was of “Southern” heritage and it was she who inspired her daughters’ imagination with “weird fantasy stories” (Beasley 279, 280). Young Gertrude was schooled at the Snell Seminary in Oakland, California, but left one year before graduating to follow her sister into the theatre. She had become notorious for sneaking out of school to go see plays. Her vacations were spent on an aunt’s ranch in Calaveras County, central California, where she learned to ride a horse and enjoy the outdoors. “This is the end of your freedom.” Rankin warned her, and he was true to his word. McKee Rankin would dominate her life for the next fifteen years.

McKee Rankin was born in Canada near present-day Windsor Ontario, across the border from Detroit, Michigan. Like his young protegee, Rankin ditched school to join the theatre. His dreams were thwarted by his parents several times until he finally decided he would join the Union Army to fight in the Civil War. His father, Colonel Arthur Rankin, a Canadian politician, was already in hot water with the Canadian Parliament for offering his services to President Lincoln to enlist recruits for the Union Army. Canada was officially neutral, but, still under British rule, she favored the Confederate side because of Britain’s connections to the southern cotton industry. Parliament decreed he would lose his citizenship if he did not cease fighting another nation’s war. Both Colonel Rankin and his son were forced to give up their military plans. McKee Rankin’s mother and grandmother decided a career in theatre was preferable to losing him on the battlefield, and in 1863, Rankin happily left Canada for the theatre district in Chicago. McKee Rankin rose to the status of “matinee idol,” and went on to form one of the first touring stock companies in America. An extraordinary talent and a superlative teacher of dramatics, McKee Rankin was not, however, endowed with financial acumen. His career was fated to be one of feast and famine, and he would share these fluctuating fortunes with all who joined forces with him. The actress who ultimately became “Nance O’Neil” rode the Rankin roller coaster as the pet of his mid-life crisis. At the age of fifty, Rankin would virtually abandon his second wife, renowned actress Kitty Blanchard, and their children, to devote himself to his “great discovery.”

Within a year of her debut, Rankin had decided Gertrude Lamson’s stage name should be Beatrice O’Neil, in honor of the Irish actress Eliza O’Neil. The Rankin Company went on to tour the states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, and Nebraska.

By the time they reached Denver, Colorado, Rankin billed his ingenue as “Patrice O’Neil.” Under this second stage name, the actress was given the title role in Trilby, a stage adaptation of a George Du Maurier novel. Rankin soon faced copyright infringement charges (one of many during his career), but he continued running the play off and on throughout the lengthy court battles. The company headed for a tour of the southern states, and during this expedition Rankin finally decided that Gertrude Lamson should be dubbed, “Nance O’Neil.” Nance, perhaps getting a bit of her own back, progressed in referring to McKee Rankin as “Mr. Mac,” onward to plain “Mac,” and eventually (and inexplicably) to “Tony.”

Late in September, 1895, the company reached Washington, DC. Nance O’Neil was suffering from exhaustion. Without a doubt, she was a young professional with drive and determination. Actors of the Victorian era lived and worked at a grueling pace, traveling and performing almost non-stop, with a “repertoire” of roles. They might perform several different roles in different plays within the same week. Most often they were poorly paid, captives of their production companies, much the same as their later counterparts would be tied to the Hollywood studio system. McKee Rankin pushed O’Neil, and she allowed herself to be pushed, seeing him as her only route to success. After a year and a half of touring, carrying the responsibility for the demanding leading roles, and enduring the constant tempest of Rankin’s management problems, Nance was overdue for a vacation. She was about to turn twenty-one, and already she had seen a lot. She spent five weeks in New York, rejuvenating herself by visiting the museums and theatres. Without Rankin, she joined the company of The Land of the Living, which produced standing room only audiences in Harlem, before embarking on a tour which lasted twelve weeks until burnout finally hit Nance with a nervous breakdown. Back in New York, she landed in a hospital for fifteen weeks. Rankin came to her rescue, paying her medical expenses and lending moral support while she convalesced. Indebted now, Nance would remain solely with Rankin until 1908.

Nance returned to the stage for a one week stint in Philadelphia in October, 1896 with the play Judge Not. Rankin was not satisfied with the play, and his company retreated to New York to work on it. By November, most of the cast had been replaced and they were on the road again with the play retitled New York As It Is, finding success in Minnesota and Pennsylvania. Rankin then tried two weeks on the vaudeville circuit, making enough money to reopen the play at the Murray Hill Theatre in New York, retitled again as True to Life. Nance O’Neil was an immediate hit. Critics began to laud her as an overnight sensation; a young artist with great potential for stardom. Once more they took the show on the road: New York, Canada, the Midwest, and Washington, DC.

In 1897, Rankin returned to the Murray Hill Theatre in New York to cast O’Neil in a series of plays, and at the same time, he opened the McKee Rankin School of Acting. He used the school to search out new talent, giving bit parts in his company to the best students. In the title role of Leah, the Forsaken, a part that would become a mainstay of her theatre career repertoire, Nance O’Neil’s performance prompted one critic to say, “Emotional roles are unquestionably her forte.” She would go on to play Camille, Magda, and the role of Nancy in Dickens’ Oliver Twist. Audiences were shocked by the realism O’Neil brought to the role of Nancy, particularly the scene where she is beaten to death by Bill Sykes. The beating audibly took place off stage, and the actress returned on her knees, bruised and bloodied, begging for her life before finally expiring. The critics called the performance “an animated chamber of horrors.” (Beasley 303). Wherever Nance played the role, audiences came in droves.

By 1898, the company returned to San Francisco, where Nance received a triumphant homecoming. Renaming being one of Rankin’s passions, he had since reincarnated Leah, the Forsaken into The Jewess. The San Francisco Bulletin claimed O’Neil “ran upon the stage as the weird, wild, impassioned, scornful Leah, the Jewess . . .The people were breathless, watching her wonderfully tragic figure and listening to her baritone voice that is so full of expression.” Nance finished off the successful run by portraying Elizabeth, Queen of England. From San Francisco, they were off to Los Angeles. In November, they set sail for Hawaii. Nance was a favorite of the Hawaiian royal family, who showered the actress with gifts. Prince David Kawananakoa was said to have serenaded her at her hotel. This was merely the beginning of Nance’s international adoration. The company was renamed the Nance O’Neil Company.

McKee Rankin had a bad reputation for mismanagement, and he was widely criticized, particularly in the New York theatre circles, where it was foretold that Rankin was destined to ruin Nance O’Neil’s career. In effect, they wanted to keep his rogue company out of the established New York theatre syndicate. Rankin decided the best way to fight this block was to establish O’Neil internationally. They journeyed to London, England, remaining there most of the summer of 1899. The London theatre scene, being almost as exclusive as that of New York, was a hard sell, although O’Neil won over the critics as always. Rankin considered touring in England, but failed to find the necessary financial resources, and the company returned to America.

In February, 1900, the Rankin troupe embarked on a ship out of Vancouver, Canada, en route to Australia via Hawaii. A plague had invaded the islands, and they were unable to stop in Hawaii, although disappointed admirers tossed long garlands of floral tributes to Nance from the docks. They stopped briefly in Western Samoa, where Rankin and O’Neil toured the home of the late author Robert Louis Stevenson. From there, it was on to Sydney, Australia. They opened with Magda on March 10, 1900 at the Theatre Royale in Sydney. About her opening night jitters, Nance would later say, “When you first look over the footlights at that sea of calm, critical faces you realize that you are at the ends of the earth, thousands of miles from home, and that that night’s performance is make or break with you. I shall never forget my opening night; it was so wonderfully, so unbelievably successful! The stage covered with flowers! The men on their feet cheering! It was all so wonderful to me. I was utterly unknown to them; unborn, so far as they knew, except for the usual preliminary press notices–it was so wonderful it didn’t seem real!”

The tour of Australia lasted most of a year, and they did not journey onward to New Zealand until December 19, 1900. Before embarking on that next leg of the tour, Nance and company were taken on a journey through the tropical jungles into the Hot Lake District, where two Maori guides took them to see the poi-poi dance of the native people. Nance was allowed to participate in a ceremony involving the activation of a geyser by dropping soap into it. A fan shaped body of mist and water rose 500 feet, reflecting a prism of colors. A Maori princess named Papakura spread garlands in Nance’s path as she left. The company played in various venues around New Zealand for three months before heading back to Australia, where Nance purchased a number of jewels, including a ring said to have been worn by Marie Antoinette.

During August, they journeyed to Hong Kong and Singapore. India was on the agenda, but Rankin failed to secure a theatre. The troupe did, however, perform privately for the Gaekwar of Baroda, who presented Nance with elaborate gifts, among which were an elephant and fifty yards of silk.

In September, the company arrived in South Africa, which was at that time in the midst of the Boer War. After performing in Cape Town, they embarked upon charitable performances for various soldiers’ relief funds, and visited refugee camps. Nance was entertained by Lord Baden Powell, and received a raw diamond from the mines.

They were unable to perform in Johannesburg, as the town had been placed under martial law, threatened by an impending siege.

En route to Egypt, the company stopped at Mozambique and Dar-es-Salaam, sailing along the Red Sea to the dock at Suez, then boarded a train for Cairo. There was a successful performance before the Khedive in the Khedival Opera House, which was renowned as one of the world’s greatest theatres. Rankin and O’Neil became guests of the Khedive’s household. Nance fell in love with Cairo, and Rankin arranged for her to spend the summer at Giza. The Egyptian government provided her with a personal servant. Archaeologist Mauriette Bey taught her to ride a camel, and Nance was carried up to the top of Kheops’ pyramid. Nance called it the happiest time of her life.

In August 1902, the remaining members of the company embarked a ship for London. They stopped in Athens to see a classical Greek play in an open-air theatre. Nance’s next stop was Paris, where she purchased more jewelry and had the silk from the Gaekwar of Baroda made into a dress.

Although Nance’s second crack at London heralded critical acclaim, Rankin was besieged with problems. Somehow the money ran out over the course of a mere months time and he was soon cabling to America for funding. Eventually, Nance O’Neil had to pawn her jewelry to finance their return home. Following a down period, they returned to San Francisco in 1902. This was a wise move for Nance’s second homecoming: she was returning triumphant from a world tour. Performances were quickly sold out. Nance ran for ten weeks at the Grand Opera House. The mayor presented her with a crown of gold laurel leaves. The money poured in, weekly receipts averaged $10,000, with a profit of $40,000 after only eight weeks. Rankin arranged for Nance’s jewelry to be returned from London.

1903 was a veritable roller coaster ride of success and disaster, ending in Chicago where a lengthy battle with a theatre owner had Rankin and O’Neil embroiled in a lawsuit. The saving grace was the arrival in Chicago of Sam Shubert, who signed them to do three weeks in January 1904 at the Shubert’s Columbia Theatre in Boston. Rankin had to borrow the money for their train fare.

Nance O’Neil would retain a base in New England for the next several years.

In January 1904, Nance O’Neil took Boston by storm. Rave reviews for her opening night at the Columbia Theatre led to a steady increase in ticket sales. After three weeks the company had to upgrade to the Tremont Theatre, as the Columbia was viewed as too low brow by Boston’s elite. Rankin hoped the move would increase profits. He was broke, and still losing money. The move worked, and Boston high society came to the Tremont in droves, with women dominating the attendance at the matinee performances. The women in the audience, said the Boston Globe, “. . . gave vent to their emotions and to their enthusiastic admiration for the wonderful acting of the gifted young star by a copious flow of tears at various times during the performances and by repeated curtain calls.” Nance was wooed by Boston’s moneyed and literati, inundated with invitations, fan mail, and gifts. Few of these invitations were accepted, however, as Nance remained somewhat reclusive, choosing to work hard at her craft with daily rehearsals. Her run lasted until April, when she set out on a tour of Massachusetts. By May, she was back in Boston due to popular demand. Nance O’Neil’s farewell performance of the spring season included favorite scenes from her various plays. After the final curtain, a laurel wreath with the words “Queen of Tragedy” was placed over the footlights to the delight of the ecstatic crowd.

O’Neil, Rankin, Ricca Allen (a loyal female member of the company), along with their servants and Nance’s menagerie of pets, settled into an eighteenth-century mansion at Tyngsboro, Massachusetts called Brinley Farm. During June and July, Rankin commuted between the estate and Boston, where he taught a course of twenty-five lectures on dramatic art and the ethics of drama. Contrary to popular belief, Nance did not own the Tyngsboro estate outright. Although it was purchased in May 1904 from the Adamant Plastic Company for $15,000, a Boston resident held a mortgage on the property for $7,500 and an attempt was made to foreclose that August. Somehow this was paid, and by 1905, Nance O’Neil was listed as a co-owner with one Benjamin A. Levy, whose identity remains obscure. By May 1906, Nance’s name was crossed out on the assessors records, and Levy’s remained (Beasley 387).

Where Lizzie Borden first saw Nance O’Neil perform is unknown, although she certainly had ample opportunity to see her in Boston, Providence, or any of the company’s many venues around Massachusetts. The popular consensus is that it was at a performance of Macbeth in Boston, and that Lizzie had been moved by Nance’s portrayal of Lady Macbeth’s horror at the blood stains on her hands. This may very well be myth, as it fits all too neatly into the Lizzie Borden legend. Apparently, Lizzie first made friends with Ricca Allen, and through Ricca she arranged to meet Nance at a summer resort near Lynn, Massachusetts in 1904. From there, Lizzie became a kind of groupie to the O’Neil troupe. The actors did not judge Lizzie, but instead enjoyed her generosity through the parties she hosted for them both at her home in Fall River (Maplecroft) and at Tyngsboro. How deep the friendship became between Lizzie and Nance is not known, although it is clear O’Neil took advantage of Lizzie’s money.

During the years at Tyngsboro, all of Nance O’Neil’s money went to McKee Rankin. She had signed power of attorney over to Rankin in 1898. Their contract stipulated that Rankin took all of her receipts, invested her money as he wished, decided all of her professional matters, kept charge of her bank accounts, and took half of her earnings. Foolishly, Nance renewed this agreement in 1904. According to author David Beasley (McKee Rankin and the Heyday of the American Theatre, 2002), Rankin took advantage of Lizzie Borden’s “infatuation” with Nance. Rankin had a predilection for borrowing money from everyone with no intention of paying them back, believing the rich could afford to support the arts. Lizzie had kept an accounting of various loans she made to Nance. In 1905, Lizzie wrote a letter to Ricca Allen to complain about the outstanding loans. Ricca passed the information onward to Nance in a letter of her own. Ricca herself was owed $225 by O’Neil, having to pawn her jewelry to raise that amount, and she had also borrowed $50 from Lizzie Borden on behalf of McKee Rankin. It is unlikely any of these loans were ever repaid.

Reports that Lizzie Borden was writing a play for Nance could have been a perversion of facts made through gossip. During the summer of 1904, O’Neil asked Boston novelist Thomas Bailey Aldrich to write for her a modern version of Judith, one of the regular plays in her repertoire. Aldrich complied, and the play opened in Boston that October as Judith of Bethulia. Lizzie, spending as much time as possible with Nance during that period, would have been aware of this. It is always possible that Lizzie tried to impress O’Neil by also attempting to write for her, but since no such play was ever produced, the truth of the rumor remains unknown.

November 1904 saw O’Neil back in New York opening at the Herald Square Theatre in Magda. In sharp contrast to her New England triumph, the New York critics were merciless. The attacks included McKee Rankin, “For just how much longer will Miss O’Neil permit Mr. McKee Rankin to spoil whatever chance she may have, or even will have, as an artistic and financial feature of the American drama?”

Thomas Aldrich wrote to a friend in New York—

She ran up against the Syndicate; against a clique of ill-spoken critics in the interest of Mrs. Fiske, who saw a dangerous rival in the new woman; against that provincial spirit which in New York will forgive anything on earth excepting a first success in Boston—just as Chicago will praise anything New York condemns. During the last ten days or so Miss O’Neil has suffered such persecution as would have crushed any literary man I know. She has borne it all uncomplainingly, doubtless with bitter tears in secret . . .I love her for her modesty, her sincerity, and her nerve. Miss O’Neil has a hundred faults but she has genius. She is the only woman on the English speaking stage who possesses the gift of tragedy.

The brick wall of New York did serve to help O’Neil elsewhere, and the company embarked on a successful tour of New York State, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. Returning to New York in April 1905, O’Neil opened with Macbeth to a much kinder reception. However, by May, Rankin and O’Neil escaped once again to San Francisco, Hawaii, and Australia. On the run from lawsuits and creditors, they hoped to recoup funds through those tried and true venues.

Rankin left the troupe in Australia to return to California in an effort to set up a North American tour for 1906. O’Neil played in Toronto, Canada in mid-April. Known as “Toronto the Good,” it was then still a puritanical financial outpost of the British Empire. O’Neil drew meager crowds there. Critics called her play Monna Vanna “indecent in idea and materialization.” While in Toronto, the company received news of the devastating San Francisco earthquake. Their main concerns were for friends, particularly Rankin’s daughter Agnes, who did indeed survive the quake. However, Rankin had shipped a large amount of their properties, scenery, and costumes to San Francisco several days before the disaster. These were indeed lost, costing the troupe thousands. Nance O’Neil declared bankruptcy in May 1906.

Nance did not spend the summer of 1906 at Tyngsboro. A creditor had a $200 judgment against the property for landscaping services. Rather than deal with it, Nance spent that summer in Paris.

The days of Nance’s partnership with McKee Rankin were numbered. Following the bankruptcy, Rankin set up several deals with other theatrical management groups, but in each case, he stayed true to form: expenses were lavish and profits disappeared. Some time between 1907 and 1908, the Tyngsboro estate was sold. The famous New York Shuberts signed Nance to a five year contract in 1908, retaining Rankin as stage manager. In addition to Rankin’s usual mismanagement, his drinking had progressed to overt alcoholism. Victor Harmon, a representative for the Shuberts, reported, “O’Neil is as queer a woman as I have ever known in this business, but I don’t see how any woman could stand for an old ‘Soak’ like Rankin about them. Rankin spends all his money on Champagne and Rum–drank two bottles of Champagne after we arrived here [Cincinnati] before breakfast Sunday morning.” The deal went as bad as all the rest, and by December, the Shuberts wanted out. Nance O’Neil paid a visit by herself to the Shubert’s head office and negotiated a deal whereby she was to run the company without Rankin. Nance then announced to the media that she was withdrawing Rankin’s power of attorney over her. Author David Beasley explains the split as a result of Nance falsely accusing Rankin of firing troupe member Clara Bracy, a woman Nance considered as a mother figure. However, it is far more likely that Nance O’Neil was simply fed up with the antics of McKee Rankin. She was in her mid-thirties by then and the bankruptcy had probably served as the last straw. By 1908, she had given Rankin the years of her prime, and after having stayed loyal to him through all the years of tumultuous highs and lows, she finally saw the need to cut him loose. Her career was constantly in jeopardy, her finances a mess, and there was no telling when the next failure might be her last.

Nance’s deal with the Shuberts turned out to be a bust. Although they paid her a salary for her first season, they reduced this to a percentage of the profits by the second season. They did nothing to promote her, nor did they secure for her any promising roles. Eventually, the Shuberts simply loaned her money, suggesting she play the vaudeville circuit and pay them back from her earnings. Likely the Shuberts had set up the O’Neil Company from the beginning, seeing a chance to rid themselves of the competition by forming a false alliance with them when the chips were down. Her career was saved by the intervention of Broadway producer David Belasco, who wanted to use Nance to help him launch an American production of a French play called The Lily. The play was a success. Rankin went on to fight several futile lawsuits against all and sundry, but the split from Nance was never reconciled. When Rankin died in 1914, Nance did not attend his funeral.

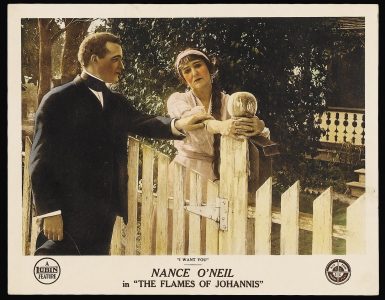

During the production of The Lily, a British actor named Alfred (Freddy) Hickman played the role of Nance’s younger brother. A friendship was formed between them, and when Nance left The Lily, Hickman became her manager. Together they did Broadway, summer stock, and vaudeville. Hickman was married to actress Blanche Walsh (coincidentally, they had met while performing Trilby), who died in 1915. Hickman and Nance were married in 1917. Beginning in 1912, Nance also embarked upon a film career, which lasted until 1932. She appeared in both silent films and “talkies,” including a progressive 1919 film short with Hickman and Tyrone Power Sr. entitled The Mad Woman which dealt with teenage sexuality and other adolescent problems. Thirty-three films featuring Nance O’Neil are known to exist. Her sense of the dramatic made her a natural for silent films, and in this new media she recreated several of her famous stage roles. Her theatre career continued until after World War II. Although she never again experienced the phenomenal successes she had with McKee Rankin, she also did not suffer the incredible lows. With Alfred Hickman, Nance seemed to finally find a sense of balance, and her career became respectable, if not one of great stardom. To her credit, there do not seem to be any reports of further financial fiascoes following the departure of McKee Rankin.

Alfred Hickman died in 1931. Nance O’Neil continued to work more than a decade following Hickman’s death. She lived a comfortable widowhood in New York until she was 89 years old. At the ripe old age of 90, Nance O’Neil died February 7, 1965 at the Actors Fund Home in Englewood, New Jersey.

Sources

Beasley, David. McKee Rankin and the Heyday of the American Theater. Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2002.

Rebello, Leonard. Lizzie Borden: Past and Present. Al-Zach Press, 1999.

Spiering, Frank. Lizzie. Pinnacle Books, 1985.

Williams, Joyce G. Lizzie Borden: A Case Book of Family and Crime in the 1890s. T.I.S. Publications, 1980.