by Kathleen A. Carbone

First published in Winter, 2009, Volume 6, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

A day born of October and the sun

In silver-tissued glory smiling came,

And touched the leaves and grass with gold anew:

The lake, a dream in lazulean blue

Flashed back the opal tints, and heart of flame,

And from its depths one face, and only one.

Emma Playter Seabury

In our electronic age of newspeak, an Internet search for “Nance O’Neil” will bring four words—a quasi-sentence to describe a life. These four words will lead anyone who is not a student of theater history to dismiss a once brilliant star of the American stage to a tittering naughty corner of the imagination. The sentence includes the three “L words” of social doom. Google “Nance O’Neil” and the result is this: Lizzie Borden’s Lesbian Lover.

This anti-legacy has been brought to further renown in Frank Spiering’s inspired work of fiction, Lizzie, in which the sensationalist spreads the astonishing rumor that Lizzie’s “relationship with Nance was a blatant homosexual affair.”1

Were she alive today, there is little doubt that Miss O’Neil would be . . . well . . . horrified that this is what is left to her memory in lieu of her art, her work, and her life. Her acquaintance with Lizzie was but an idiosyncratic blip in a long and colorful, if inscrutable, existence. And it is this enigma that has held me hostage to Nance O’Neil.

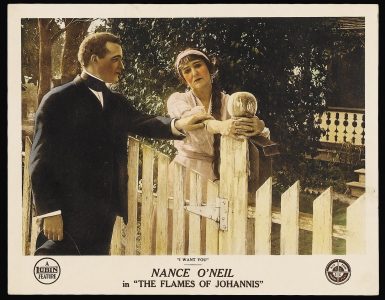

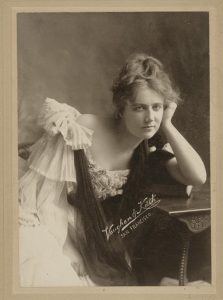

Look at her images online in the New York Public Library Digital Gallery, a part of the Billy Rose Theatre Collection. In one photograph she is winsome and lacy, in another she is surly, then she is dewy and wistful—fragile as a breeze. In another image she looks like she could pull a plow or deck a longshoreman. Her signature is a rushed scrawl as she whisks out the stage door, underlined twice, or a careful note written at her neat desk late at night with a glass of sherry. She was meticulous about her art, delving into a character’s psyche and rehearsing relentlessly. She was the consummate actress, yet she refused to kiss her stage lovers on the lips.2 Later on film, she was the matriarchal joke, a top-heavy diva with a stentorian, mocking voice. On stage, she was grace and divinity incarnate.

This duality, this mystery, surrounds her memory, and makes one long to find the woman who was Gertrude Lamson—the actress who became Nance O’Neil—and the woman who existed beyond the shadow of Lizzie.

However, the fact remains that Lizzie led me to Nance. If you are reading this and you are not a theater enthusiast, Lizzie probably led you to Nance too. Like many of her acting contemporaries, Nance O’Neil’s fame is lost to posterity. There are no theaters, no scholarships, no acting awards, no schools of drama, and no methods of acting that bear her name. Most of her fellow actors who went on to claim such accolades also won fame and fortune through film. Nance did not. If the film industry in Hollywood did not appreciate Nance O’Neil, the feeling was mutual. Here was another Syndicate, an industry churning out cheap thrills and matinee idols and passing itself off as art. How indeed, she asked, could one create a relationship with the audience when there was “a sheet of plate glass” between them?3

In film, one creates a rapport with the camera. Nance O’Neil brought live audiences to their feet and made them cry, feeling their approval or disdain, in person. The boards creaked beneath her six-foot frame, her voice carried into the dime seats; her very fingertips could be seen from the furthest seat in the house. She boldly walked into scenes barefooted (unheard of in her time) and even turned her back to the audience, allowing the considerable musculature of her back to evoke her emotion—a move that frequently baffled critics who, in turn, tore her apart in their confusion. Nance accepted praise and weathered failure with the strange combination of grace and humility that denotes the true Star. She was, if anything, a creature of the stage.

And it is the gift of Art that is kissed by the Divine. A film in its entirety may be considered Art: Bergman’s Seventh Seal, with the opening shot of the sky, and the voiceover reciting Revelations; or Kurasawa’s Ran, with the unforgettable battlefield scenes. Yet we don’t really think of the actors in these great films as Divine. The gods inspired their directors instead. On the stage, this is reversed. The director may have indeed been inspired during the production of a play, but it is the actor who hopefully channels the Divine night after night. For two or three hours, the audience can feel the presence, warm and breathing, of the Muse who speaks through a truly inspired actor on the stage, directly in front of them.

The camera has come between actor and divinity. Nance O’Neil noted that it separated actor and audience. A bad take winds up on the cutting room floor: a terrible hair day is quickly restored and a temper tantrum accommodated by cooling down the lights and a cup of cocoa in the dressing room. There is always a safety net. But where the gods are concerned, there are no safety nets.

Nance O’Neil flew without a net because the spark of divinity gave her wings. It lived in her voice, her tragedy, her grace, and her fearlessness.

Born on 8 October 1874, in Oakland, California, to George and Arrie Findley Lamson,4 Gertrude Lamson was the second of their two children. Arrie Findley was originally from Virginia, and George Lamson was, like Lizzie Borden, a New Englander. Born in Lowell, Massachusetts, an industrial mill town not unlike Fall River, George struck out for San Francisco during the gold rush of 1849. Arrie’s sister Effie and her family also settled in California.

When the gold rush proved a losing gamble, George Lamson turned to a less chancy profession and auctioneered cattle. He was also a devoutly religious man who ran a tight ship at home. Arrie Findley had a flare for drama and entertained her daughters with art lessons and ghost stories. This odd combination of paternal Yankee Puritanism and maternal Southern Gothic would long hold a fascination for their younger daughter.

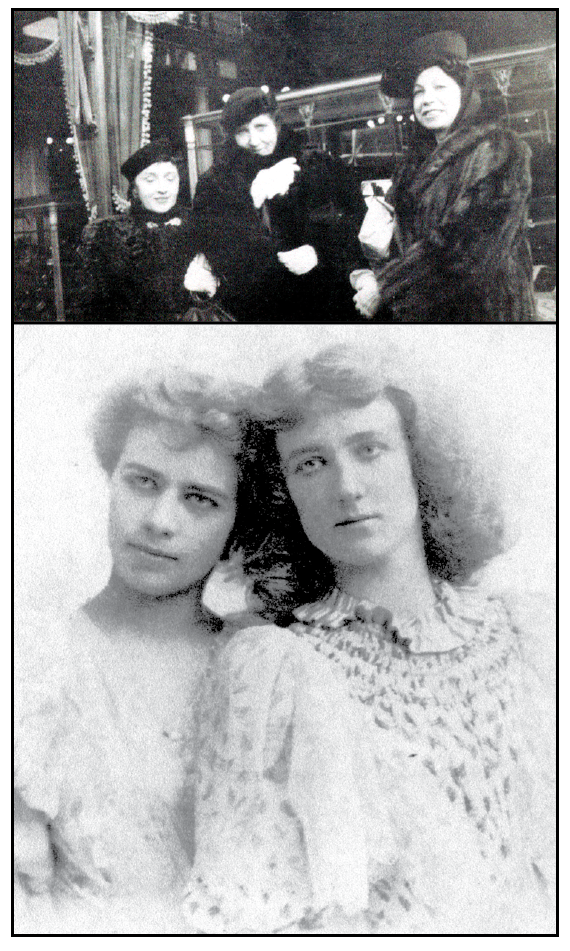

Gertrude’s older sister Lillian left home at seventeen to pursue a career on the stage. Unfortunately, not much is known of her stage career, but we know that Lillian achieved some success touring around the country. She was occasionally billed as Lizzie Lamson.

However, one can imagine what her daring departure for the footlights meant for Gertrude. We can be sure that the admonitions flew and the parental reigns were tightened as a more conventional life was mapped out for the remaining daughter.

But the Lamsons were in for another surprise. At eighteen, their tall and beautiful Gertrude followed in her sister’s footsteps and left home a year before graduation. Although Lillian’s departure no doubt inspired young Gertrude Lamson, she probably would have sought out the stage anyway. As one who made her own way in life, Gertrude Lamson’s pursuit of a life on the pioneer stages out west was an unacceptable path for a young lady. Throughout her twenties, she toured with the McKee Rankin Company to Europe, Hawaii, Australia, India, and South Africa. By the time she was thirty, she had seen more of the world than most of her fellow Americans ever would in a lifetime.

The idols of her youth were tragedians: Italian Tommaso Salvini (1829-1916), and Lucille Western (1843-1877). Gertrude managed to sneak away from boarding school and into a theater in San Francisco to see Salvini when he toured the United States in 1889. She also saw Eleanora Duse and Sarah Bernhardt, but she preferred the work of Western.

Lucille Western, a brilliant actress who suffered with an addiction to heroin, died before Gertrude Lamson was born. But she was well noted in books, periodicals, and tales from those who’d known her, Rankin among them. Western was a renowned “emotional” actress who won fame in many of the parts that Nance O’Neil would later succeed in, including Nancy in Oliver Twist, Camille, and Lady Isabel in The New East Lynne. O’Neil was so proficient in the roles that Lucille Western’s mother presented her with Western’s own prompt books.5

Gertrude Lamson struck out for the stage at an auspicious time. It was an era between the romantic histrionics of Bernhardt and Duse, and the overwhelming slam of vaudeville and bad female roles in Hollywood. It was an era when the American public was attracted to traditional theatre as it was becoming more popular and accessible.

At the dawn of women’s Suffrage she portrayed powerful, if doomed, women. And even if most of her plays had to end on a note of warning to the image of a strong female heroine (Camille, Leah The Forsaken, Hedda Gabler, Lady Inger of Ostrat), from her reviews one senses that Nance O’Neil’s portrayals left the audience with the memory of that power rather than the chastised (or deceased) female at final curtain. Her Nancy in Oliver Twist was no shrinking violet. She was nearly as burly and brutish as Bill Sykes. It’s no surprise that she failed as Juliet, as one critic noted, “She touches the ingenuous, girlish side lightly, and she does the heavier scenes with considerable discretion, … although her heavy voice breaks out once in a while and mars the effect. … She is fitted for work of greater caliber.”6

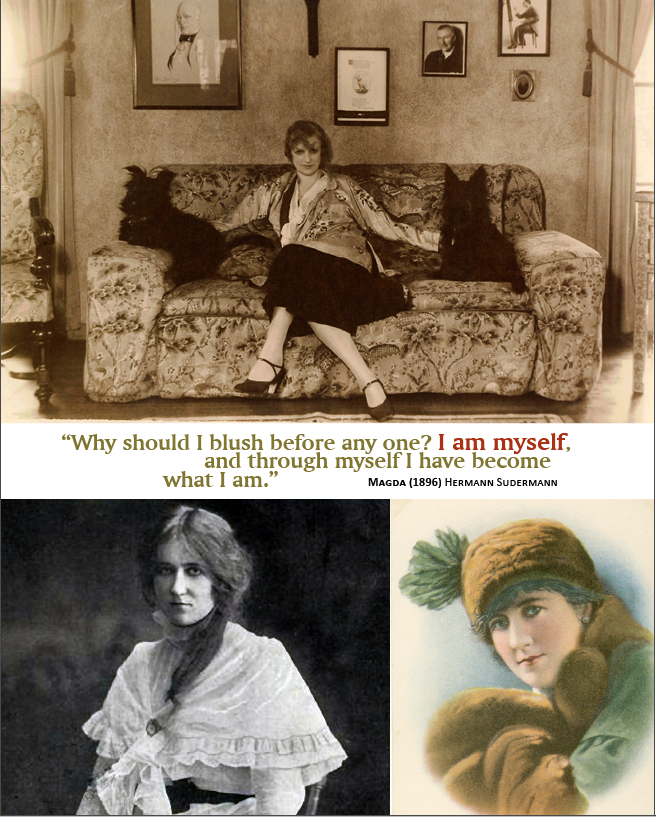

Hermann Sudemann’s Magda, one of her earliest and most successful roles, was a play she insisted upon opening each tour with for “good luck.” The story reads a little bit like an adaptation of O’Neil’s own life: Magdalene leaves home at eighteen to pursue a life upon the stage. Her tyrannical, militaristic father denounces this. Magdalene shortens her name to Magda and through years of hard work, succeeds and becomes a renowned singer. The play opens with her triumphant return home. The lines, spoken by Magda, must have rung true for O’Neil, and one can imagine the authenticity she no doubt brought to the role.

Here, she defends the profession of acting to her angry father, who remains ashamed of his disobedient daughter:

Why should I be worse than you, that I must prolong my existence among you by a lie! Why should this gold upon my body, and the lustre which surrounds my name, only increase my infamy? Have I not worked early and late for ten long years? Have I not woven this dress with sleepless nights? Have I not built up my career step by step, like thousands of my kind? Why should I blush before any one? I am myself, and through myself I have become what I am.7

And here, she speaks out for women of her time:

See how much the family with its morality demand from us! It throws us on our own resources, it gives us neither shelter nor happiness, and yet, in our loneliness, we must live according to the laws which it has planned for itself alone. We must still crouch in the corner, and there wait patiently until a respectful wooer happens to come. Yes, wait. And meanwhile the war for existence of body and soul is consuming us. Ahead we see nothing but sorrow and despair, and yet shall we not once dare to give what we have of youth and strength to the man for whom our whole being cries? Gag us, stupefy us, shut us up in harems or in cloisters — and that perhaps would be best. But if you give us our freedom, do not wonder if we take advantage of it.8

The difference with the American version of the play, rewritten by director McKee Rankin for O’Neil, is that in the original German Magda’s father shoots and kills her in the final scene; whereas Rankin has his Magda triumph as the father suffers a stroke and dies before he can pull the trigger. It was a unique and sometimes disturbing turn for an audience of the era. Rankin was, if anything, ahead of his time. It’s little wonder that they worked so well together for so long.

Just after her nineteenth birthday, in October of 1893, Gertrude Lamson had approached McKee Rankin with an introductory note from a local theater critic. The note supposedly advised the director to “kindly discourage her” from the stage, but Rankin gave her a chance.9

By then, Rankin was nearly fifty and had become one of the most successful and popular actors/playwrights/directors/managers in America. A Canadian by birth, Arthur McKee Rankin soon fled the life of a government clerk that his parents had planned for him to seek a life on the American stage. With perseverance, he rose through the theater hierarchy from “walking gentleman” at ten dollars a week in Chicago, to the leading man in the Arch Street Theater in Philadelphia, known as the “first temple of drama in America” run by Mrs. John Drew, actress, manager and matriarch of the Drew/Barrymore family. Two of Rankin’s daughters, also actors, contributed to that dynasty’s famous gene pool. His daughter Gladys “Dido” Rankin married actor Sydney Drew, and his daughter Doris married Lionel Barrymore.10

By the time Rankin met Gertrude Lamson, he had been married twice and had a daughter older than her. With an unerring eye for talent and presence, he saw a future in Lamson and he carefully groomed her for the stage with increasingly demanding parts. By her mid-twenties, she basically carried the company, which soon bore her name. On more than one occasion she and Rankin were arrested for what would today be considered copyright infringement. This consisted of staging works without the full consent of the author. Rankin frequently even rewrote entire scenes and changed characters (usually to the betterment of the work), and was notorious for leaving the writers in the lurch financially.

However, Rankin was a congenial and handsome charmer who was often able to talk his way out of a payback over a bottle of beer. He was also one of the most innovative and compelling actors of his time, sometimes referred to as “the American Salvini” (despite his Canadian origins). He was an acquaintance of John Wilkes Booth, whose wardrobe he came into possession of when, on the night of the Lincoln assassination, the steamer that Wilkes had shipped his trunk onto was wrecked in the Gulf of St Lawrence. The Canadian authorities, unaware of its owner, eventually sold the trunk for salvage a few months later. Rankin’s brother, who was a civil servant in Quebec, happened to buy it. Thinking that the costumes within might be of use to McKee, he shipped them to him.11

Rankin led Gertrude Lamson from a nervous walk-on to become one of the greatest tragediennes to ever walk the American stage. However, her given name would not do. They chose a stage name that was a combination of Nance Oldfield, an actress of the seventeenth century who was currently being portrayed in America by Ellen Terry in a play by Charles Reade,12 and Eliza O’Neil, “an equally celebrated tragedienne of the period.”13

After two years of successful touring in the west with Rankin, Nance O’Neil went to New York without him. It’s unknown exactly why she left, and given the tight leash that Rankin kept on her in later years, it is hard to imagine him sending his young star off on her own to the big city. However, she joined another troupe in New York, took on the leading roles, and eventually toured with them for twelve grueling weeks on the road. While in Minneapolis, Nance suffered a nervous breakdown and returned to New York. Exhausted and despondent, she was admitted to a hospital for an extended recovery.

Feeling desperate and alone, uncertain of her future, Nance spent nearly four months in the hospital. It could not have been a very happy recovery for her. Mental health services were unknown at the time, and actresses in general were not the American royalty that they are today. But Rankin came to her side and stayed by her until she finally recuperated and returned to him. It was a very long time before she would leave his company again. In that era there was little opportunity for autonomy for an actress. Without money or a powerful family, a single woman was obliged to find a manager. And then she became obliged and beholden to that person.

Rankin discovered and trained O’Neil, but he also kept her dependent upon him. He lived vicariously through her as his own health declined into alcoholism and obesity, and his long years of non-payment of debts eventually drove her from him. She was once the highest earning actress under his directorship (in San Francisco, 1903, she averaged $10,000 a week in receipts), and was bankrupted under his mismanagement. Rankin more than once referred to money as “filthy lucre.” He struggled with an altruistic need to separate art from the material world of business and commerce, and this was his downfall. He treated his own and others’ hard earned dollars as disposable, not worthy to bother about. But, by refusing to worry about the earnings of his acting company, it vanished as quickly as it was earned. Nance had unfortunately signed power of attorney over to Rankin when she was twenty and, as a result, most of what she earned came and went as well. In 1903, when Rankin had been blackballed by the theater syndicate, she wrote to manager Frank McKee in desperation to get a booking, “I don’t care what the salary is, provided I can get enough to live on. You can have all the profits . . .”14 This seemed to have been the extent of the business acumen passed onto her as Rankin’s protégé.

David Beasley’s biography of McKee Rankin gives a well-researched look into the career and travels of Nance O’Neil, but the book is about Rankin. Beasley attributes her success, and even her well being, almost entirely to Rankin. The general public at the time thought much the same. An unmarried actress under the wing of an older manager meant little else to audiences than a kept mistress, and, were she successful, she was his creation. Early in her career, Nance portrayed the young ingénue in Trilby, a singer who is hypnotized by her manager, played by Rankin. It’s not surprising that the fictitious characters of Trilby and Svengali carried over into the public’s imagination.

But who was she, this enigmatic “great beast of the stage” (as she once described herself after a particularly rough critical drubbing)? Surely there was more to Gertrude Lamson’s persona than being known as Rankin’s acting student or presumed lover of Lizzie Borden. As someone who was so identified through her work, we can look to her reviews for some idea of the presence she must have carried on the stage.15

The Literary World magazine wrote that Nance O’Neil was “easily the finest English speaking actress … Physically, she is splendid, a superb figure, a handsome face, a wonderful voice, and every movement is grace itself.”16

In San Francisco, a critic described her voice as

Sometimes a whisper, sometimes a guttural, harsh growl, and again it is vocal velvet, while in climaxes it is like a great organ. Yet every variation of tone compels you to listen, and there is no escape. She uses it in so many ways that one fancies that she has exhausted every variety, and then a new tone will come that will show there is evidently no end to its variations.17

Her countenance was also fodder for critics:

Once ungainly in height and lack of figure, she (Miss O’Neil) is now commandingly handsome, and in possession of a figure that would delight the heart of the sculptor. Her whole style is leonine and she has a voice whose depth and power is unknown in any other present-day star.18

In December 1909, her portrayal of Odette in David Belasco’s production of The Lily met with this incredible headline and review in the New York Times:

Flare-up of Genius Shown in ‘The Lily’

By Nance O’Neil Acting Tremendous

Scene at the Stuyvesant Theater.

The Audience Goes Wild!

Any one who happened into the Stuyvesant Theater last evening about a quarter to eleven might have supposed himself suddenly translated into an asylum for the insane, such was the enthusiasm which followed the end of the third act of ‘The Lily’. . .19

The Lily is a rewrite of a French drama in which the eldest daughter of a tyrannical widower sacrifices herself to a lifetime of servitude to her father after the untimely death of her mother. In this Gallic tradition, the eldest daughter who performed this onerous duty was called a lily. In act three of the play, when the obsequious Odette finally stands up to her father when he attempts to beat her younger sister, the audience was driven to its feet. The review goes on:

Miss Nance O’Neil, hitherto moving quietly about . . . a strange, subdued figure suggestive of lavendar [sic] and old lace, the willing victim of a tyranny that could find its only justification, if any, in an inherited sentiment . . . Miss O’Neil played the crucial scene with a simple economy of means, never apparently striving for effect, her full, clear, bell like voice suddenly growing warmer and more pliant under the stress of feeling, and, for all its power seeming to give forth only part of its store.20

This performance earned Nance O’Neil an unheard of thirty-six curtain calls.21

Robert Sullivan, an assistant stage manager, described her portrayal of Lady Macbeth in the sleepwalking scene. He recounted her technique of stage whispering the dialogue like a babbling child’s rhyme, which grew into a “ghastly wail.” With her eyes wide, but clearly sightless and dreaming, she backed into a wall and awakened in hysterics.

We were afraid of her when we had to run on after that curtain. She was still screaming, rent by great, big, terror-stricken sobs. Then, when the people were through with making her bow, she stood quite worn and spent in the middle of the stage pitiably asking for her shoes. The poor woman had actually played that scene barefoot and was cold, tired, and worn out.22

Even then, the Boston/New York theatre rivalry was in full swing, as what flew in Boston tended to meet with harsh reviews in New York; the words that came from an early critique of O’Neil’s Magda were “crudity” and “amateurishness.”23 These descriptions would follow her throughout her career, especially during her uphill battle with the Klaw/Erlanger theater syndicate (euphemistically referred to as the Theater Trust), when they tried to shut her out:

as crude an uninformed technically as lacking in trained resource as were her previous efforts.24

Star she may be but comet never! . . . Miss O’Neil is as crude as ever. . . . She glows with the dusky splendors of stained glass, and falls into its straightened, archaic attitudes. This sort of thing does very well for Boston. Boston is itself a thing of archaic attitudes . . . The plain truth is that in fifty-nine minutes of the hour Miss O’Niel [sic] is an awful bore. She is as strained in the simplest moment as in an agony of passion. . . . At the least suggestion of a dramatic moment, she and her company turn the backs of their heads together, like sculptures . . . As it is, she is fated to be her own burlesque.25

Miss O’Neil has a kind of massive beauty . . . but it is not evident that she has any great intelligence.26

There were innumerable vituperative, even libelous, reviews from the New York critics who hoped to insult her right off the stage when she and Rankin tried to break down the doors of the theater syndicate. By the early 1900s, this affiliation of managers had effectively locked out anyone who didn’t agree to their strong-arm tactics, which included, of course, demanding a big chunk of the house receipts in return for bookings. Her friend, author Thomas Aldrich, wrote of her:

New York will forgive anything on earth excepting a first success in Boston—just as Chicago will praise anything New York condemns. During the last ten days or so Miss O’Neil has suffered such persecution as would have crushed any literary man I know. She has borne it all uncomplainingly, doubtless with bitter tears in secret. . . . I love her for her modesty, her sincerity, and her nerve. Miss O’Neil has a hundred faults, but she has genius. She is the only woman on the English speaking stage who possesses the gift of tragedy.27

Little is known of her personal life at this time, or at any other for that matter. She traveled extensively during her career, and summered in the south of France with a group of “bachelor girls” like herself, and shared a house there with fellow actress Peg Bloodgood (Beasley 488). She also loved to paint landscapes when not working on stage and, in 1910, several of her oil paintings were exhibited at the Actor’s Fund of America’s Fair at the New York City Armory.28

In her early thirties, after a decade of touring a world seen through the plasticine bubble of show business, Gertrude Lamson longed to discover herself and explore her roots, particularly, the Yankee Massachusetts heritage of her father. Perhaps she had begun to suspect that it was not their differences, but their similarities, which were the real clues to who she really was. George Lamson had left the settled industrial city of Lowell, Massachusetts, for an unknown pioneer west, hoping to strike it rich. Gertrude Lamson had left her secure and loving family for an unknown world on the stage and had struck it rich. But not through luck—she had striven, worked, and denied herself many of life’s comforts and joys for the stage. She had stuck it out with the determination and steadfastness of a…well, a stubborn Yankee.

To find herself through her father, she went back East in 1904. She wanted to study his people, their language, and their manners. She had been warmly welcomed in Boston; in fact one periodical claimed that the city was “Nance O’Neil-mad.”29

This quest would lead her to purchase a 146-acre estate in Tyngsboro, Massachusetts, on the Merrimack River, near Lowell, her father’s birthplace. Brinley Farm became her haven in the off-season for three summers. Unfortunately, the manners of her neighbors in Tyngsboro left much to be desired. If Boston loved her talents, the suburbs did not. Residents insulted her as she passed them on the sidewalk and as she walked from the train station, and she eventually packed up and left. However, she loved Brinley while she summered there, and her Massachusetts pilgrimage resulted in the passing acquaintance of a certain devoted fan, producing that reputed notorious friendship with Lizzie Borden that she would never outlive.

In 1909, she parted with Rankin and was briefly managed by David Belasco. It was with Belasco that she had the triumph in that same year as Odette in The Lily. But, aside from that success, there were no starring roles for Nance under his management. Belasco’s complicity with the Syndicate was probably to blame; they had never forgiven her for staying with Rankin for so many years and refusing to tow their line. She found herself idle under Belasco and, in 1911, she broke with him.

When she married fellow actor Alfred Hickman in 1917, Nance O’Neil was forty-two. They continued to work together in many Broadway productions, with Hickman now performing as her manager. When the tidal wave of film nearly drowned theater, they both found work in film, with Hickman taking on the duties of teaching acting students, as well. Nance recreated some of her more famous stage roles in silent films, but by the time of the talkies in 1929, Hollywood didn’t know what to do with a Nance O’Neil. She was older, and years of stage acting and smoking had deepened her already stentorian voice. She was too strong, too frightening, and too damned tall! However, she was professional, showed up on time knowing her lines, and took direction without fuss, so the film industry did what it could with her. For the most part she was cast as unmarried female villains, or into comedic roles that accentuated her height and her remarkable voice. It was less than worthy of her talent, but it paid the rent.

Nance O’Neil knew where she belonged and kept an apartment in New York, where she continued to act. She received much critical acclaim as matriarch Dona Raimunda in Jacinto Benevente’s The Passion Flower, but critic Alexander Woollcott of the New York Times recorded a performance that seemed brilliant one minute, abysmal the next:

No, it is not in these hilltops of Benevente’s play, but in its valleys that Miss O’Neil goes astray. It is because her acting is no continuous movement, but a series of explosions. She is remarkable in the amazing scene between Raimunda and Norbert, but in the still more exacting passage, the hour when Esteban makes full and beseeching confession of his forbidden love for his stepdaughter, she is lamentable. This, for a potent actress who can listen, which is half the secret of acting, is the great hour of the play. You look to Miss O’Neil for guidance and you find her either carefully arranging some preposterous pose or not thinking of the scenes at all. She still sits and gazes upon Esteban, but spiritually she has gone out for a brief rest in the wings. . . . then she lifts her tremendous and matchless voice in her final cry of accusation . . . 30

Woollcott revealed an often-overlooked quality an actor needed in order to transcend above the ordinary: an ability to listen, to act, and react silently. In this, at least in the performance described above in 1920, Nance O’Neil, by then, was lacking. She excelled in the portrayal of what was then politely called emotional roles. That was press talk for characters who displayed a “series of explosions” on stage; it’s no wonder that she never truly blossomed as a romantic figure. She was too strong, and when she failed it was usually for overdoing it.

What this meant for her off the stage was that a great chunk of her life was spent just preparing for the on-stage moments. It took up much of her energy, leaving little free time. In a Boston Globe interview later in her life she admits, “The public little realizes the long hours of rehearsing, of studying, of trying on clothes, buying shoes, having pictures made. All that glitters isn’t gold, and even the brightest career must have hours of despondency.”31

It’s no wonder that anyone portraying such tragic and emotional characters night after night would experience downhearted moments; that has lead many an artist to drink and drugs, even suicide. But if Nance suffered for her art, she did not succumb. She continued to paint, travel, and enjoy life with many friends and admirers. At one point, she asked that her friends call her “Diane,” indicating an actor’s variable sense of self. She had a dramatic belief in Fate, and a mystical side that pulled her through some of the more earthly disappointments. “My art is my world. I love it,” she told Grant Wallace in an interview.

An actress must know the despair of her heroines. She could have experienced those passions in other lives, thousands of years ago. Acting lifts [the actor] out of the sordid, narrow life, and thrusts him into a bigger world where he stands in mute handclasp with the larger, cosmic emotions of the gods.32

On Broadway, one of her co-stars was a bright and lovely younger actress named Julia Duncan. Nance and Julia had struck up a friendship on and off the stage, and when Alfred Hickman passed away of a sudden stroke in 1931, Nance moved back to New York for good. At some point, she and Julia Duncan moved in together at the Gorham Apartments.

Throughout her career and her travels, Nance O’Neil kept in touch with her family. She and her parents had reconciled after the first shock of her departure, and she returned to San Francisco on tour more than once to packed houses and great reviews. She and her father wrote to one another and he forgave her impetuous and unconventional flight from home. Perhaps he considered that she had inherited her personality from him. Her phenomenal success surely must have counted for something, even to a staunch New Englander, as it had been attained through hard work and self-sacrifice, like his own.

In 1946, when Nance was seventy-two, she had a young visitor from California—her four-year-old third cousin, Marie.

Marie Cruzzetti-Lintz’s great grandmother, Effie (Findley) Richardson, was the sister of Arrie Findley Lamson, Nance O’Neil’s mother. Mrs. Cruzzetti-Lintz remembers receiving cards and letters in the 1940s while Nance was living in New York with her companion, Julia Duncan. When Marie visited New York in 1946, Nance and Julia gave her a copy of Alice in Wonderland, which she still keeps today.

Mrs. Cruzzetti-Lintz related that Nance’s sister, Lillian Lamson, who passed away of unknown causes at age thirty, was married to film star William Desmond. He was a popular matinee idol of early cinema, famous in western serials. Unfortunately, the family did not have any information on Alfred Hickman, to whom Nance was married from 1917 until his untimely death of a stroke in 1931. The family was unaware of any friendship between Nance and Lizzie Borden. Mrs. Cruzzetti-Lintz did however clear up one point of contention between Lizzie Borden aficionados: Nance was pronounced with one syllable; rhyming with chance, she was not called “Nancy.”

Some time in the early 1950s, poet Eugene Walter was invited by his friend, Joseph Cameron Cross, to the theater and a late dinner. A third person soon joined them for the evening and the sharp-witted Walter described the encounter thusly:

[Cross] didn’t say who was coming along, but it turned out to be this woman who was terribly tall. I mean, she was tall. Even though she occasionally sagged, she constantly remembered to stand straight. . . . And she had dyed red hair which she obviously did herself because it was different shades in different patches of hair. There was one bit over her left ear which was almost purple. She must have gotten the wrong mix or something. She had dead white skin. And she must have put on that mascara with a teaspoon, you know. Just dug it up and went flip, flip, and dug little holes to look out of. And she had rouge in the old-fashioned way. I mean right on the cheekbones, a well-defined patch of rose red. She was dressed in black, something silk or satin that was an old dress, cut on the bias. There was some black lace somewhere. And she had two wristwatches. She had a fancy little wristwatch that was cold, and she had—it wasn’t a Mickey Mouse watch, but had something on it like that, with a plastic band. Right together these two watches. And she was wearing tons of pearls. To my eye, it looked as though half of them were real and half were fake. Then she had this flashy diamond ring. And she was carrying—God bless the lady; I had not seen one since I left Mobile—she was carrying a reticule. In the fabric that matched her dress. She was swinging her reticule. And she had a little brass-headed fruitwood cane, very slender, very elegant. She must have been ninety-five.’ Joseph Cameron Cross introduced her, ‘Oh, Eugene, you know Nance O’Neil.’ 33

Walter further described his unusual dinner mate:

She was smoking cigarettes two cigarettes at a time. And someday I must do a drawing or painting of what I saw as I glanced down and saw the very beautiful gold Cartier watch and the Felix the Cat watch. The diamond ring, one cigarette lit, two pieces of toast, another cigarette in a little ashtray smoking there, and a fork. . . . I thought: They don’t make them like they used to.34

He related that O’Neil ordered “the usual” from the waiter, which turned out to be “a washbin of Welsh rabbit,” “a mountain of toast,” and a “gallon of beer.” No wonder Walter never forgot her.

In a snippet of conversation in which Nance O’Neil discussed Lizzie Borden, Walter described this passage as Nance’s reply, after he got up the nerve to ask her about Lizzie:

I won’t say I was nervous being in a house with Lizzie Borden. After all, there were a lot of us together. You can be sure we looked out for each other and made a point never to be alone with her. And to notice how sharp her dinner knife was. But there was one thing I do remember as striking me. She would often make me repeat for her at teatime Medea’s famous speech.

Often the night of thunder I have a message from the gods on high.

They ask me why I have not slept. Why in the morning I will touch no food.

Then I’d tell them of my sleepless night and why I did not sleep.

Because, I tell them, this house smells of blood.35

Walter described the setting for this teatime recital as “Lizzie Borden’s house on the Hudson.” But after fifty years, a world traveler like Walter might well have forgotten the name of Tyngsboro, Massachusetts, on the Merrimack River, where Nance and Lizzie had in fact met a few times during the summer of 1904.

Walter further described O’Neil, whom he admired greatly as an actress (he was a theater student) and as a star:

She was like Tallulah. Using her powers for the greater good. Rewarding those people who happened to be in the same restaurant with a performance. She knew what she was doing. At least one fork clattered. But everyone else just put down their fork. She was a prima donna in the best sense. Prima donna usually means self-centered or self-consciously defined center type, male or female. And usually unaware of other people’s rights or reactions or necessities. But a real prima donna has the generosity of spirit which includes putting the shy at ease. Noticing the invisible. Putting down the bore gently. Tallulah was a perfect example. It has to do with cat and monkey sense of humor. And this, Miss O’Neil had. . . . I’ve found that the greater the talent, usually the gentler, kinder, and especially the more humorous they are.36

There is a full-length portrait of Nance O’Neil as Lady Macbeth in the Player’s Club dining room in New York. Painted by her friend, artist Paul Swan, it is magnificent—reminiscent of John Singer Sargent’s “Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth.” But Sargent painted Lady Macbeth sedate in her madness, eyes glazed over, standing full length, and grandly crowning herself. Through Swan’s eyes, Nance O’Neil’s Lady Macbeth is alert, crouching, gathering her skirts about her, eyes shifting. She is ready. She is the lookout as Macbeth murders Duncan off scene. The impression Swan drew from Nance’s portrayal was one of plotting and carrying out the deed. A beautiful villain of action who is not afraid to conspire and to act.

Swan also produced several drawings and a naturally posed oil painting of Nance O’Neil as herself. The painting depicts her as he must have known her—a frequent guest at his New York apartment. She is leaning forward as though listening intently to someone. The feeling is serene: Nance in her seventies, peaceful and attentive; the true diva who would listen kindly, notice the invisible, and put the shy at ease.

Nance O’Neil died on February 7, 1965 at the age of ninety. She had been a resident at the Actor’s Home in Englewood, New Jersey. Her obituary featured a less than complimentary photograph of her, with the succinct, un-sugar-coated announcement: “Nance O’Neil, 90, Tragedienne of Stage in Early 1900’s, Dead.” It mistakenly stated that “no member of her family had ever been in show business,” effectively forgetting Lillian, and William Desmond, her sister’s widower.37

Artist Paul Swan attended the funeral in New York, but her ashes were interred in Alfred Hickman’s lot at the Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, California. It is unknown if these were, in fact, her wishes. It is possible that she left no arrangements for burial and that, as Hickman’s widow, her remains were simply sent to his plot in California. There is, sadly, nothing to commemorate her in New York or Boston, where they knew her and sought her, where she drew full houses, and where they loved her.

The acting genes continue today through this line of the family. Nance O’Neil’s sixth cousin is a successful actress in the theater in California, and there is little doubt that her once famous great cousin would be enormously proud.

Today, there are several films available on DVD that feature Nance O’Neil. Inviting a few friends over, we watched a scene from Royal Bed. The scene included all of the main characters having a conversation. Asking my friends, two of whom are actors, “Who is the most compelling character in the scene? Who is the character your eye follows?” both acting friends replied, “The queen. You can’t take your eyes off her. And that voice! The other characters are bland compared to the queen. Whoever the actress is, she steals the scene. Everyone else is visibly straining to act.” The queen was, of course, Nance O’Neil.

When watching her enter the scene, one can still see the grace and beauty that she had on stage in her prime. And her voice still carries in a manner that is never heard in actors today; one can imagine her bouncing it off the walls of Carnegie Hall without even trying. This film was a bad comedy, but it was clear that she understood comic timing and expression, even though her true gift was for tragedy.

O’Neil herself once compared the expression of emotion to music: “It is like feeling among the strings of a harp for the chords that are playing themselves in your heart. The touch of one alien string will bring a discord to the melody that you are trying so hard to make. Leave out one note and the harmony is spoiled.”38

No wonder Lizzie loved her. Who wouldn’t have? She was simply Divine.

Eyes of the World. From the private collection of Stefani Koorey.

Endnotes

1. Frank Spiering, Lizzie: The Story of Lizzie Borden (NY: Random House, 1984) 208.

2. “Behind the Scenes,” Kansas City Post, 28 September 1910.

3. David Beasley, McKee Rankin and the Heyday of the American Theater (Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2002) 438.

4. Sources differ as to the spelling of Gertrude’s mother’s name and her place of birth. Federal Census records for 1880 show her name as “Arre” and that she was born in Tennessee. However, Gertrude’s descendent, Marie Cruzzetti-Lintz, reports it spelled “Arrie” and her place of birth Virginia. There are no other earlier census records for an Arrie or Arre in either Virginia or Tennessee to validate one spelling or birthplace over the other. Consequently, we are giving precedence to Ms. Cruzetti-Lintz’s account.

5. Beasley 292.

6. San Francisco Chronicle, 14 July 1903.

7. Hermann Sudermann, Magda: a play in four acts (Boston: Lamson, Wolff & Company, 1896) 122.

8. Sudermann 157.

9. Helen Fitzgerald Sanders, “Nance O’Neil: Her Travels and Her Art.” Overland Monthly October, 1906: 212.

10. Beasley 49.

11. Beasley 46.

12. Beasley 281-282.

13. New York Times, 8 February 1965.

14. Beasley 346.

15. Beasley 375.

16. Literary World, February 1904.

17. San Francisco Bulletin, 20 September 1898.

18. Daily News (Denver), 15 April 1903.

19. New York Times, 24 December 1909.

2. New York Times, 24 December 1909.

21. Beasley 412.

22. Beasley 364.

23. New York American; (n.d), Robinson-Locke Collection, New York Public Library.

24. “The ‘Lady Macbeth’ of Nance O’Neil,” New York Times, 26 April 1905.

25. “Nance O’Neil and Poetic Realism,” New York Times, 4 December 1904.

26. New York Times, 11 October 1908.

27. Thomas Aldrich, 30 November 1904, The Judith of Bethulia Papers, Temple University Library.

28. New York Times, 8 May 1910.

29. The Critic, September 1904.

30. New York Times, 14 January 1920.

31. Boston Globe, 27 January 1946.

32. “A First Impression of Nance O’Neil,” Grant Wallace, San Francisco Bulletin, 1 December 1902.

33. Eugene Walter, Milking the Moon: A Southerner’s Story of Life on This Planet (NY: Three Rivers Press, 2001) 110-111.

34. Walter 112.

35. Walter 112.

36. Walter 112-113.

37. New York Times, 8 February 1965.

38. St. Louis Dispatch, 26 April 1897.

Note: Special thanks to Marie Cruzzetti-Lintz for her gracious and generous help with this article.