by Michael Brimbau

First published in April/May, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

If you mention the word “library,” images of majestic neoclassic structures flicker across my mind, such as the one in New York City, with its ageless Beaux-Arts architecture, along with Patience and Fortitude, two magnificent silent stone lions guarding its entrance. Or perhaps the formal and refined appearance of the Boston Public Library, adorned with sweeping arched windows and white Renaissance Revival masonry. But a library is a great deal more than a clever design or expensive building, nor does it need to be constructed to monumental scales. In truth, the real worth of these buildings is measured by the precious bindings waiting on their shelves, the art decorating their walls, and the small treasures that are hidden in some concealed dusty corner or tucked away and forgotten in an archival box in some sequestered back room.

Of course, these major institutions are the exception. Most libraries are but small and modest places, with budgets that depend on cake sales and donated used book fairs to aid in their survival. Small town USA is freckled with these petite cultural depots. No place rightfully can validate itself as a “town” without one. Along with finding the latest best seller there, be it fiction or non-fiction, a small town’s soul is housed in these precious literary guilds. They are much more than a place for casual reading. Many are true protectors of the past, the surrogate historical society of their community, and custodian to a small town’s past. Before we can wear the badge of pride for our communities, we must first learn about those who preceded us. If you live east of the Kickemuit and west of the Lees River in Massachusetts, such a place would be the Swansea Free Public Library.

Although I have lived in near-by Fall River all my life, it’s with sour regret that I must admit the only visits I have made to the Swansea Library were to attend its sponsored used book sales. Oh yes, and to sample the tasty brownies and oatmeal cookies donated by Friends of the Library for such events. It was not until teaming up with Stefani Koorey, in researching material for The Hatchet, did I discover the true value of this small but cherished institution, and the pertinent relationship between Swansea and my hometown—or the friendship and kinship between Lizzie Borden of Second Street and the Gardners of Swansea at the head of Mount Hope Bay.

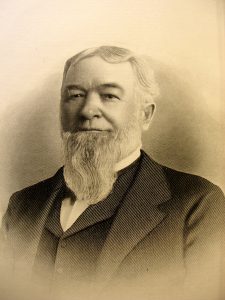

The Swansea Public Library was dedicated in September of 1900. The building was first named after Frank S. Stevens who donated the land on which the library sits. Stevens was a wealthy manufacturer, banker, and State Senator. Along with these attributes, he was a generous man. Those living in Swansea Village became the recipients of his philanthropy in the way of land and public buildings that he donated and had built for the town. A short half block away, the Stevens mansion still sits proud and elegant. Sadly, Stevens died two years before the Library’s dedication and never witnessed the true value of his literary contribution.

The Swansea Library’s architect was Henry Vaughan of Boston. Vaughan, of English extraction, was noted for his church architecture, which includes the Washington National Cathedral in Washington D.C. Although he was famous for building in the Gothic vein, the library was constructed in the Elizabethan style to complement the Romanesque approach of the town hall, and the Gothic elegance of the village church, between which it sits. Its exterior walls were erected in informal but warm colored granite, trimmed with red Potsdam sandstone outlining its corners, windows, and doors.

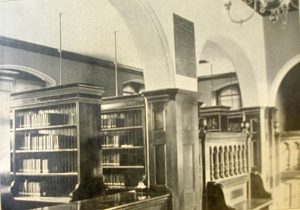

The striking red front door is quickly forgotten once one enters and is greeted by the rich wood interior, whose elegance is frozen in time. At the time of its dedication, the stack room was designed to hold 10,000 volumes. In the beginning, much of its stock was donated by private town folk. By the time it opened its doors, the library had acquired some 2,450 volumes, was sustaining a circulation of over 8,685, and to its success, issued 561 library cards. Still, though somewhat a small building, the space lends itself to a cozy and comfortable visit for reader and researcher alike. The main reading room, which is situated to the left as one first enters, is a snug but welcoming 27 x 16 feet in size. Its cathedral gambrel style ceiling, embellished with wood mouldings and simulated exposed rafter beams, adds to the impression of larger space. The toasted yellow brick of the fireplace (with a 6 foot high mantle) almost scales the entire north wall, 16 feet to the ceiling. Still, with a liberal-sized reading table and chairs situated in the center of the room, the atmosphere is one of a homey kitchen reading space, or nothing short of an Elizabethan delight. Here strangers soon become friends, and one can sit with a book and read to the library cat, Penny, who stretches and lounges in a near-by chair always ready to lend an ear and purr in appreciation. Most of the original portion of the building’s interior is enhanced with dark oak paneling, seven feet high. Above this fine wainscoting, the walls are graced with paintings by prominent local artists. Floors are planked of quartered oak that have proven themselves against a hundred years of foot traffic.

To the right, tucked towards the front of the building, in the east wing, is the magazine room. The tranquility of this little reading area can be compared to a Victorian country den or a smoking room in an old English men’s club. Proceeding forward, the circulation desk is just ahead left, where the staff always greets you with a neighborly smile. To the right is a stairwell that takes one down to the quaint but generous children’s library area. Once past the circulation counter, the back room mushrooms out. Here most of the stacks and rows of volumes, the real meat of the library, are housed. For those interested in historical study, there is a portion in the back that is occupied by the Swansea Historical Society. There, behind a secured door, sits a repository of books and ephemera, including photos and other archival documents and antiquities pertaining to the history, heritage, and ancestral study of the town of Swansea. It was here that a forgotten photograph of Lizzie Borden, as a precious little girl, was discovered by Hatchet editor Stefani Koorey, along with a treasure trove of photos of countless family members, including Gardners, Morses, Masons, and Emerys. Many of these names are familiar, to a larger or smaller extent, to students of the Borden case. For those wishing to access this material for study or research may do so by appointment by calling the Swansea Historical Society.

If memory serves me well, I believe it was Ralph Waldo Emerson who coined the phrase “the people’s university” to describe the American library. In support to this maxim is an inscription carved into the stone in the gable above the front entrance of the Swansea Library. It describes the purpose for such establishments and the reason why they must survive. Written there in Latin are the words Lego ut Discam, which translates into, “I read that I may learn”—to which I may add, “I learn so I may be.”