by Stefani Koorey

First published in Winter, 2009, Volume 6, Issue 3, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

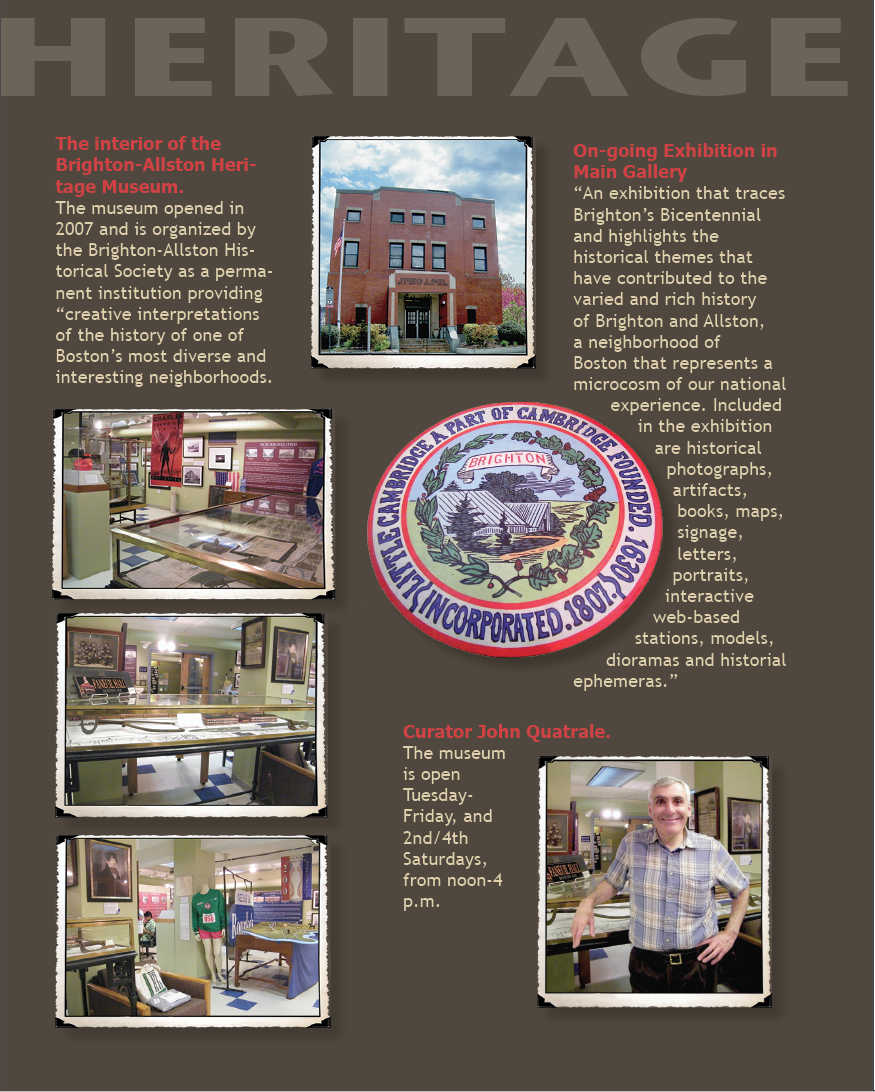

A recent Google Alert* for “Lizzie Borden” led me on an interesting adventure. The notice was a simple invitation to attend a museum anniversary party on February 27, 2010, at the Brighton-Allston Heritage Museum in Brighton, Massachusetts.

Because many Google Alerts are for blogs, news reports, and web pages that are not actually germane to my interests (due to authors who may include the words I am looking for, but have nothing of substance to say on the subject), it is rare to find anything special or significant when I follow the link to the source of the reference. But this particular announcement proved to be just the opposite—it is quite possibly a very important discovery for those who study the Lizzie Borden case.

Buried in a document that was highlighted in the Heritage Museum’s blog were the words, “Over 100 historical artifacts exhibited, including . . . a letter from Lizzie Borden . . .” Intrigued, I emailed the curator, Mr. John Quatrale, and asked lots of questions: To whom is this letter addressed? What is the subject of the letter? May I come and see it and take pictures? Would you allow me to write about it in an article for The Hatchet?

Mr. Quatrale was most gracious in his reply and I soon had an appointment to visit the B-A Heritage Museum, located about forty-five minutes north of Fall River, on the outskirts of Boston.

The Brighton-Allston Heritage Museum is housed in the basement of the Veronica B. Smith Multi-Service Senior Center on Chestnut Hill Avenue. It is a fascinating place, filled with historical objects of local and regional interest. The rooms are bright and clean, with cabinets and display cases, dioramas and maps, posters and signage, and artifacts and treasures, tastefully arranged. It is one of those places where you know you could spend a few engrossing hours pouring over the collection, and learn a great deal of interesting information in the process.

Since Mr. Quatrale was expecting me, he had Lizzie’s letter out of the case, and allowed me to read and photograph it to my heart’s content. He advised me it was difficult to decipher, as is the case when the subject of any letter is fairly obscure, though I have trained myself to the process. It is rather like reading a sort of cryptogram, where I skip over the words that do not make sense until I have finished the reading, knowing I can deduce the hard-to-read words once I have a sense of the missive’s context.

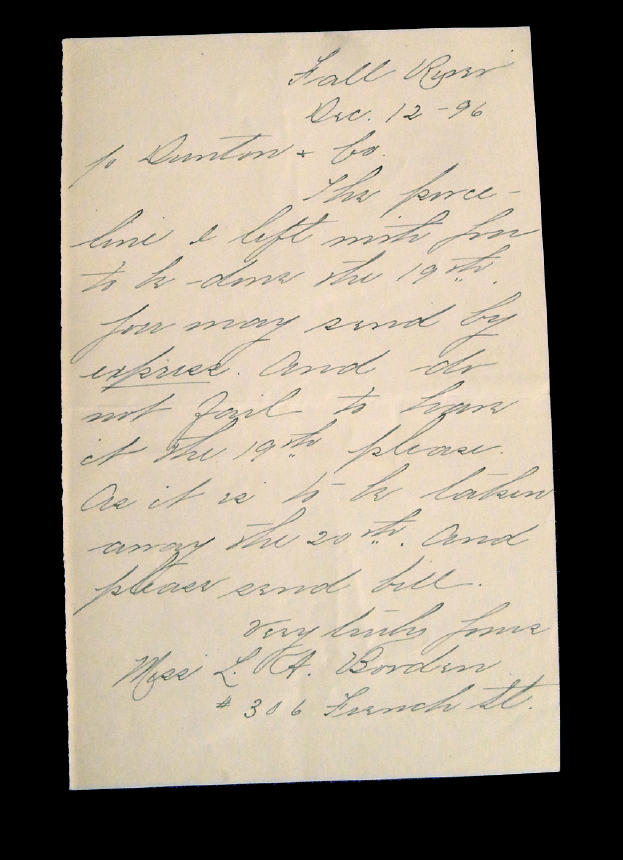

In this case, the letter is addressed to a business of some sort, Dunton & Co., and is dated December 12, 1896. This correspondence is post-trial by three years; Lizzie was thirty-six years old and living at Maplecroft with her sister Emma.

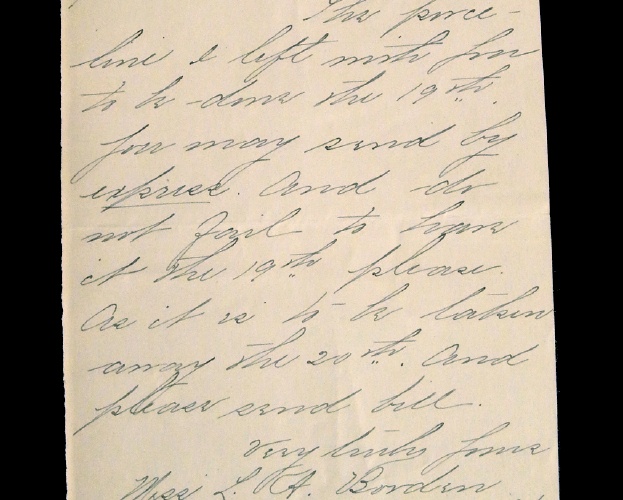

Here is an exact transcription:

Fall River

Dec. 12 -96

To Dunton & Co.

The porce-

line I left with you

to be done the 19th,

you may send by

express. And do

not fail to have

it the 19th please,

as it is to be taken

away the 20th. And

please send bill.

Very truly yours

Miss L. A. Borden

#306 French St.

A few observations are in order before the letter’s possible significance is ascertained. First and foremost, it is agreed that this is indeed a letter in Lizzie’s hand. Her distinctive penmanship is evident, as is her signature, the style of which she very often used.

She writes three sentences to instruct the recipient as to her wishes. In order for the letter to make any sense, it is assumed that the punctuation marks after “19th” and “please,” which look like periods, are, in fact, commas. The photograph of the letter (provided here) clearly shows some sort of punctuation marks where I have indicated them in the transcription. It should be noted that if the commas are periods, the letter becomes an awkward collection of ungrammatical sentences. Of interest also, I think, is the fact that she has misspelled the all-important word porcelain.

This note reads much more like a quick message than a letter of some thought and personal communication. Written as it was during the middle of December, it perhaps refers to an object that Lizzie plans to give away as a Christmas present. The letter is dated the 12th, a Saturday, and she is requesting the item be returned to her by the following Saturday. The piece will be “taken away” on the 20th, or Sunday.

Since there was, and is, no mail service on Sunday, it’s assumed that either she is planning to take it to someone, the someone is coming to get it, or she is having it delivered to someone on that date. Whichever the case, since Lizzie is sending her letter to Dunton & Co. only a week before she wishes the “porceline” returned, it is most probable that the company to which she is writing is in a nearby city.

After searching for the firm Dunton & Co. in city directories for Fall River, Boston, Providence, and Newport, the company was located in Boston, at 298 Boylston Street—Charles H. Dunton & Co., also known as C.H. Dunton & Co. They are listed in the city directory for 1899 as “importers of photographs” in the alphabetical section, as “Photograph Publishers” at 50 Boylston in the business section, and as C.H. Dunton & Co, specializing in “Foreign Photographs, Views, Sculpture, Paintings, Braun’s Carbon Photographs, Artistic Picture Framing,” at 298 Boylston Street, Boston, in the advertising section.

According to Funk & Wagnalls 1897 dictionary, porcelain is:

a translucent kind of pottery, usually glazed, existing in many varieties, according to its composition and method of manufacture, but generally characterized by a glassy fracture, clear ring when struck, homogeneity throughout its thickness, and resistance to fire, water, and all acids but hydrofluoric.

The item referred to in the letter could be a porcelain painting, photograph, art object, or keepsake. It is less likely a piece of jewelry or a plate or cup, as it would be appropriate to refer to those types of items by their usage. To call something “the porceline” is an interesting choice of words, and leaves the debate open as to its exact design for future examination.

The date of this note especially caught my attention.It was very shortly after this time period that Lizzie was accused of shoplifting two paintings on porcelain, one of which, titled “Love’s Dream,” was supposedly found at her home after an investigation. The reportage appeared in the newspapers, beginning on 15 February 1897 in The Bulletin. The next day, a lengthy account ran in the Providence Journal and the Los Angeles Times, where the headlines declared that a warrant for Lizzie’s arrest had been issued in the matter.

From here, the story took on a life of its own, appearing again in the Providence Journal on the 17th, the Los Angeles Times on the 18th, and the Fall River Daily Globe on the 19th. The Tilden-Thurber Incident, as it would forever be known, has been detailed in books and articles on the case ever since, the facts of the story changing somewhat with each recounting.

A great summation of these early newspaper reports appeared in The Hatchet in August, 2005, in the article “Lizzie and the Tilden-Thurber Incident” by Sherry Chapman. I am indebted to her research, which I will quote from here:

Here are some of the “facts” presented in the newspaper articles. You probably noted, as I first did when I read them, that they each presented quite alternative versions of events: the last one being downright mocking. I observed the following:

• The article entitled “Lizzie Borden Again” [Providence Journal, 16 February 1897: 1-2.] tells us that there were two paintings on “marble.” A salesman was in charge of selling those paintings, and the two paintings were still in Lizzie’s possession. The paper does say that the exact reason for not serving the warrant is “entirely a matter of speculation.”

• “The Borden Affair” article [Providence Journal, 17 February 1897: 1-2.] says that a painting on “porcelain” perhaps 18” in length and half that width was involved, and that the large painting was a figure of a young woman in a pose titled “Love’s Dream.” There was a second smaller painting worth less. The larger one was missing shortly after Lizzie Borden left the store.

• In “Lizzie’s Gift” [Fall River Daily Globe, 19 February 1897: 8.] we are told that Lizzie had given one of the paintings to a friend. The friend is described as the wife of a cashier of a Providence bank. When the banker’s wife brought the item to Tilden-Thurber to be framed, staff there recognized it as one of the two missing paintings. The clerks did not know the paintings were missing until the woman brought the one painting in. She told the store staff that Lizzie Borden had given it to her.

• The LA Times article of February 16, 1897 goes back to the description of the paintings being on “marble.” But an extra twist is added – that Lizzie visited Tilden-Thurber around Christmas time and shortly after the paintings were discovered to be missing.

• “Can’t Avoid Stealing” [Los Angeles Times, 18 February 1897: 2.] calls Lizzie an alleged kleptomaniac. The paintings, one a “magnificent painting on porcelain,” had been missing recently. After Lizzie left the store one day the other was missing. The reporter takes a guess that since the warrant cannot be found, maybe Lizzie did pay for the paintings and the store disregarded the salesclerk’s proclamation of thievery (25-26).

There is yet another account of the Tilden-Thurber Incident that should be mentioned. In the archives of the Fall River Historical Society is a one-page typed, two-paragraph summation of a personal recollection that was shared with the curator. There is no date on the stationary, which bears the letterhead of the Society, but it clearly details a descendant’s assertion that the person who received the porcelain painting was Preston Hicks Gardner, Lizzie’s cousin who lived in Providence. Writes Kat Koorey in the February 2008 Hatchet:

The end of 1896 retired the story of his first cousin Orrin Gardner’s engagement to the infamous Lizzie Borden, yet the year 1897 was barely new when his own family was involved in a scandal. This time Lizzie was boldly accused of stealing from his local Tilden-Thurber, in Providence, apparently as a part of her Christmas shopping expedition. The Preston Gardner name had been suppressed, at least. Lizzie had given his wife, Mary, one of the supposedly stolen pictures. She was described as a friend, but also as married to a bank cashier in Providence. The family knew to whom that referred. It was the only controversy in which his reputation was attached to that of Lizzie Borden. It was many years later that the family legend revealed Preston Gardner as the one who had settled the affair behind the scenes (25).

So, does this letter, found in Brighton, refer to this story? Is the porcelain that Lizzie needed “done” and delivered by the 19th of December, the same object that she gave to the Gardners (Preston or his wife Mary) for Christmas? If so, was the porcelain in need of repair, cleaning, or restoration and was entrusted to Dunton & Co. to do the work? Or does this letter refer, innocently, to another object that was to be given to a friend of Lizzie’s for Christmas, and is of no significance?

It cannot be known for sure, unless some other correspondence or a diary entry is found to link the Gardners to Lizzie on the 20th of December and offer up a description of the gift that they received. Another factor of note is that Lizzie’s letter indicates that the item she wishes them to work on was left by her. This means that Lizzie had traveled to Boston in the recent past and hand-delivered the item to Dunton & Co. It would be interesting to know if Lizzie’s supposed shopping expedition to Providence at Tilden-Thurber predated her trip to Boston to have the porcelain “done.”

Regardless as to whether this letter even tangentially refers to a major event in the life of Lizzie Borden, it is important for the mere fact of its existence. Few examples of Lizzie’s written correspondence are available to us (five letters, one note, and a fragment of a letter), though many may still be held by the families of the people she sent them to. A find such as this is uncommon, and makes visiting the Brighton-Allston Heritage Museum all the more worthwhile.

Lizzie Borden’s letter to Dunton & Co. is but one of many new discoveries related to the Borden story that I have made in the past two years. Traipsing through historical society records, noticing a face in a photograph, spotting a rare book on a shelf, recognizing a signature—these are the ways in which I have made my finds. This discovery was pinpointed courtesy of Google Alerts, a service that anyone with a computer can use. It was just a matter of clicking on a few links, writing an email, and driving to the location. If there is one thing that I have learned in my travels with Lizzie, it pays to pay attention.

* According to the Google website, “Google Alerts are email updates of the latest relevant Google results (web, news, etc.) based on your choice of query or topic. Some handy uses of Google Alerts include: monitoring a developing news story; keeping current on a competitor or industry; getting the latest on a celebrity or event; keeping tabs on your favorite sports teams.” You can set the search terms, type, frequency, length, and delivery address.