by Kat Koorey

First published in Spring, 2009, Volume 6, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

There was a new religion being born in nineteenth century Victorian rural America —a system of belief that eventually attracted a pair of such disparate personalities as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini, in two very different ways. One man was coaxed into absolute belief, the other into unqualified disgust.

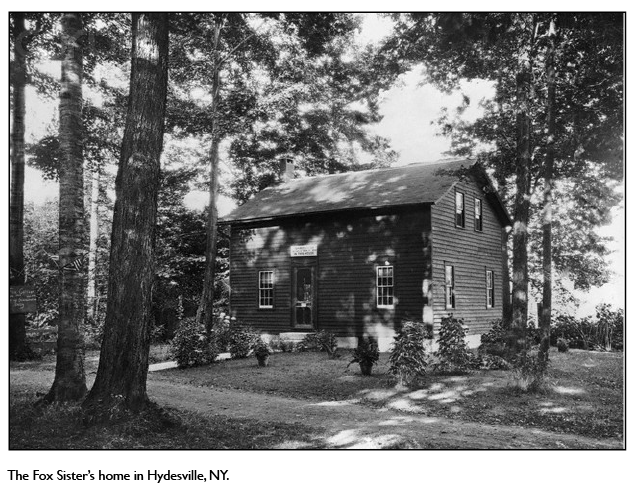

The new religion was Spiritualism, which is credited as being born on March 31, 1848, in Hydesville, New York, at the home of the Fox family. The happenings there were so rare and riveting that their story eventually shook the world and inspired a movement that continues to this day.

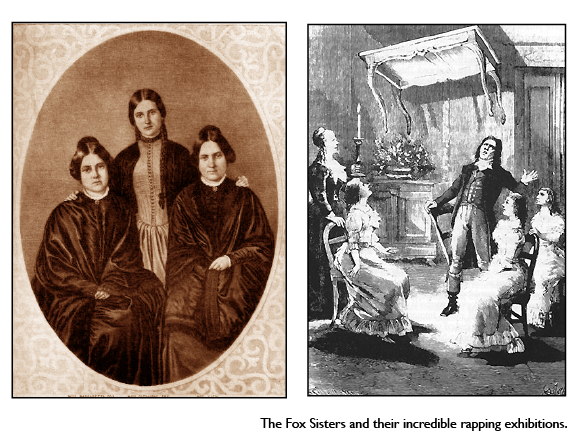

The members of the Fox family were frightened by unexplained noises in their house, which was reputedly haunted. Margaret and Kate, aged fifteen and eleven, the youngest daughters of John and Margaret Fox, responded in kind to the repeated invisible knockings on the walls that were bedeviling them, and challenged the entity to mimic them. One sister clapped her hands and the sound was repeated. The other sister gave the command and clapped her hands, with, again, an answering salvo. Soon, the spirit in their home was responding to intelligent questions with a series of raps, and identified itself through this form of communication as a past resident and murder victim.

The members of the Fox family were frightened by unexplained noises in their house, which was reputedly haunted. Margaret and Kate, aged fifteen and eleven, the youngest daughters of John and Margaret Fox, responded in kind to the repeated invisible knockings on the walls that were bedeviling them, and challenged the entity to mimic them. One sister clapped her hands and the sound was repeated. The other sister gave the command and clapped her hands, with, again, an answering salvo. Soon, the spirit in their home was responding to intelligent questions with a series of raps, and identified itself through this form of communication as a past resident and murder victim.

There had, of course, been isolated unexplained incidents in the early days of our country, notably the Bell Witch story of Tennessee in 1817, but most poltergeist-like phenomena was accredited to “Elementals” (primitive spirits of lakes, streams and trees, guarding a family or animals or crops). When this spirit responded, it seemed to provide valid information and posses some sort of intelligence, convincing many that the mind survived death.

From miles around, people visited the Fox’s home for spirit demonstrations and left frightened and amazed. When the girls split up, each traveling to stay a fair distance from the other, the rapping followed them. Visitors who interacted with the entity in these demonstrations began to have these powers to communicate as well. Obviously, the world was ready, because the phenomena spread like an epidemic over the whole eastern seaboard, and within a few years there was established a culture of practicing mediums, clairvoyants, and table-tippers conducting séances and producing manifestations, ectoplasm, and automatic writing for the credulous public.

The Fox sisters became internationally famous as they toured the country, giving public exhibitions for many years. They eventually confessed that they had no special powers, but later claimed that they had made a false confession. This same pattern of admission and denial was later repeated, as other young girls, taking advantage of situations where enormous attention was paid them for a time, would confess duplicity and then recant, always leaving promoters and devotees confused.

The Fox sisters became internationally famous as they toured the country, giving public exhibitions for many years. They eventually confessed that they had no special powers, but later claimed that they had made a false confession. This same pattern of admission and denial was later repeated, as other young girls, taking advantage of situations where enormous attention was paid them for a time, would confess duplicity and then recant, always leaving promoters and devotees confused.

The Climate In America

The climate had been ripe for such a movement to be born in America. It was the Victorian age and the era of Industrialism. The U.S. had suffered the siege of the Alamo (1836), the national tragedy of the Native American’s Trail of Tears, with preventable loss of life (1838), and the war with Mexico (1846-1848). Soon after the Fox sister’s notoriety on the U.S. stage, there followed the Gold Rush of 1849, where hordes of idealistic prospectors flowed west to make their fortunes.

The local atmosphere and conditions of western New York, in 1848, finds a cold March winter of dark days and boredom for two adolescent girls in a small family cottage. It is very possible that these world-altering events were orchestrated out of adolescent ennui. There is precedent in the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 in Massachusetts, when three young girls, aged twelve, eleven, and nine, shook a community and triggered some of the darkest days in our past. These girls mischievously accused neighbors of witchery, and nineteen people, both men and women, were tried and executed. This mischief was born of cold dark days of January, in New England, in cramped quarters, and caused, probably, by boredom.

Prior years of small pox deaths, religious differences and difficulties, and recurring Indian uprisings, influenced this historical climate. The results may seem to be a rebounding effect from the age of Enlightenment, with its emphasis on eradicating superstition, while elevating the attributes of reasoning, intellectuality, and skepticism. We cannot discount the regrettable consequences of a bored teenaged girl and her adolescent accomplice—they can affect history.

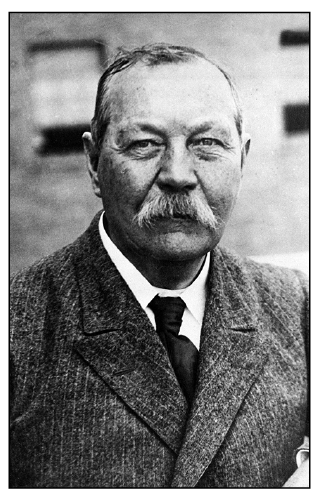

Sir Arthur

The little girls of Cottingley Fairy fame were another fraudulent duo. They came to the attention of Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), who was fascinated by their fairy photographs. It is understood that these girls did not seek notoriety, fame, or fortune, but it sought them. Sir Arthur’s acceptance of the photos as wholly and undoubtedly genuine, as true images of fairies frolicking in the beck with these beautiful children, raised him up to ridicule and tarnished the great man’s reputation the rest of his days.

The little girls of Cottingley Fairy fame were another fraudulent duo. They came to the attention of Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), who was fascinated by their fairy photographs. It is understood that these girls did not seek notoriety, fame, or fortune, but it sought them. Sir Arthur’s acceptance of the photos as wholly and undoubtedly genuine, as true images of fairies frolicking in the beck with these beautiful children, raised him up to ridicule and tarnished the great man’s reputation the rest of his days.

Sir Arthur was the one who brought these photos to the attention of the public in The Strand magazine, December 1920. Elsie Wright, sixteen at the time the photos were taken in 1919, and her cousin Frances Griffiths, who was then aged ten, had taken a camera down to the pretty place they visited and over the summer returned with photographs of each other with fairies that they claimed came and played with them at Cottingley Beck Wood. Doyle published his opinion on the photos’ authenticity without a full investigation. But, by this time, he had had his religious conversion, forsaking his perceived public position of a non-committal stance toward the psychic phenomena that he had spent thirty years investigating. He had surrendered his skepticism and embraced Spiritism after a remarkable personal experience in 1916.

His second wife, Jean, had a friend, Lily, who was chronically ill and stayed with them in their home. She had lost brothers in WWI, and began producing the phenomena of automatic writing during meditation. The writing is supposedly a product of trance, of words flowing effortlessly onto paper very quickly through the semi-conscious hand of the medium, compiling copious amounts of material that can be composed of prognostication, individual history secret to the witness, or reams of writing on elevated spiritual matters. Throughout Sir Arthur’s investigations into the occult since 1879, he had reserved judgment, saying he would not be convinced of life after death until he had a personal experience. One day, in his home, Lily, channeling the automatic writing of her deceased brother, produced that proof: a conversation was repeated that was private to Doyle and Lily’s brother, to which Doyle knew no one on earth had ever been privy.

It was characteristic of this Renaissance man, highly skilled in physical endeavors as a sportsman, and well versed in, and constantly curious about, the arts and sciences, to make an impulsive, intuitive decision to believe and, therefore, no longer question. This leap of faith was so strong and abiding, it is said that when he was notified of his own beloved son’s death he was able to pause, meditate on the passing, be happy they would meet again in an afterlife, gain strength from that solid belief, and then carry on with a scheduled lecture. At the point when he found steadfast faith, he never waivered. He determined that his mission was to bring such solace to the world, like a ministry, through his already established audience of his readership. When Lily died, Jean Doyle was consumed with feelings of guilt, wondering if anything she did, or did not do, contributed to her friend’s death. Jean tried contacting Lily, and became a practitioner of Spiritualism. The husband and wife team combined to promote the religion, traveling extensively, and investing Doyle’s earnings as an author into their mission.

Admittedly, the Cottingley Fairy girls did not conceive of their stunt in the stark, cold, dark days of winter, but they were more sophisticated children, with vivid imaginations, a Midg camera, knowledge of its use, and possessing a flair for art.

Sir Arthur was already a Knight, and a product of a Victorian upbringing—he embodied the chivalrous code toward females, giving them his honor and respect. He did believe that they had experienced fairies, and he described the little folk as existing in a state of vibration that is merely different than our own. In his romantic view, any nature walk, if the mind was attuned, could reveal glimpses of sacred spots—the habitat of secret communities of elves and fairies. Doyle felt a sense of delight in this imagery—as a contrast to the heavy, harsh realities of the slogging masses striving toward the materialism of the twentieth century. Doyle hoped the illumination of such magical beings would uplift the common folks into the contemplation of an accessible spiritual realm.

In the context of girls acting out, luring trusting adults into their fantasy, riding the wave of publicity, later confessing, then retracting the confession, these young ladies followed the pattern we have already established. Miss Wright admitted much later that the photos were figments of their imaginations. That, at least, was true. Doyle had grown up in Scotland, steeped in folklore, ghost stories, and fairy tales. His Celtic background predisposed him toward an interest in, and an understanding of, the occult—the unseen. He was writing a book on fairies at the time of his inquiry into the Cottingley case, and possibly thought the timing was fortuitous and took advantage of the publicity. He was no scheming charlatan, though, and was sincerely accepting of the photographic phenomenon, which characterized his whole attitude towards things spiritual in these latter years of his life—blind faith.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Meets Harry Houdini

It wasn’t until more modern times, in the 1970s, that author Fred Gettings, in his book Ghosts In Photographs, exposed the results of his investigation into the fairy pictures. He found nearly duplicate illustrations in a tome of 1915, Princess Mary’s Gift Book. At the time, the Bishop of London publicly criticized Sir Arthur, but Doyle continued in his interests of attending séances, lecturing, and writing, just as he always had done.

It wasn’t until more modern times, in the 1970s, that author Fred Gettings, in his book Ghosts In Photographs, exposed the results of his investigation into the fairy pictures. He found nearly duplicate illustrations in a tome of 1915, Princess Mary’s Gift Book. At the time, the Bishop of London publicly criticized Sir Arthur, but Doyle continued in his interests of attending séances, lecturing, and writing, just as he always had done.

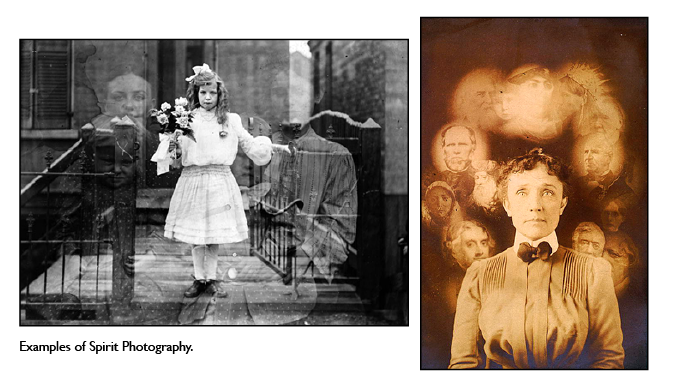

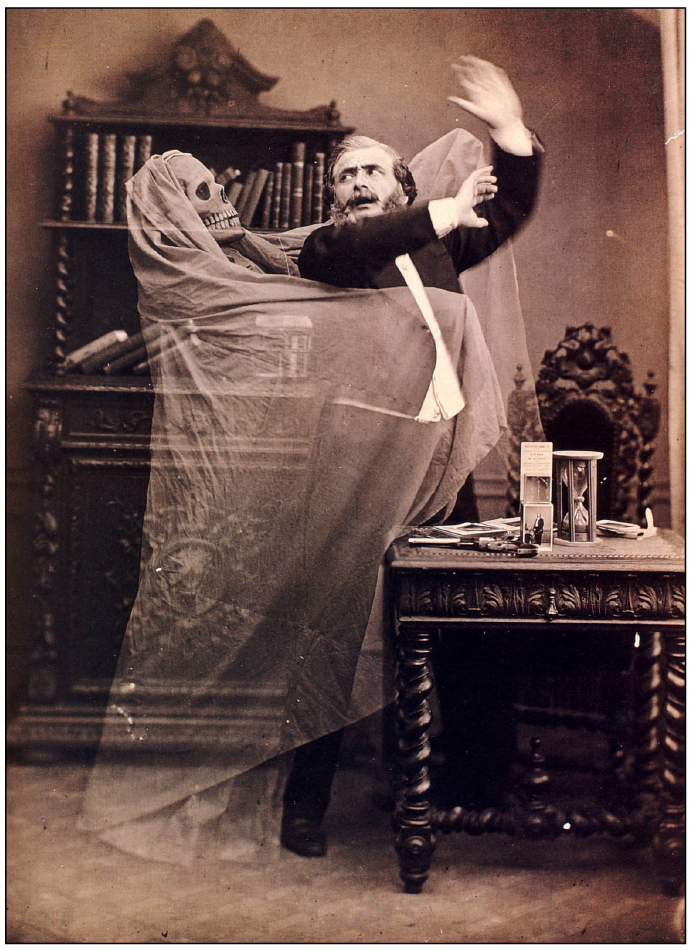

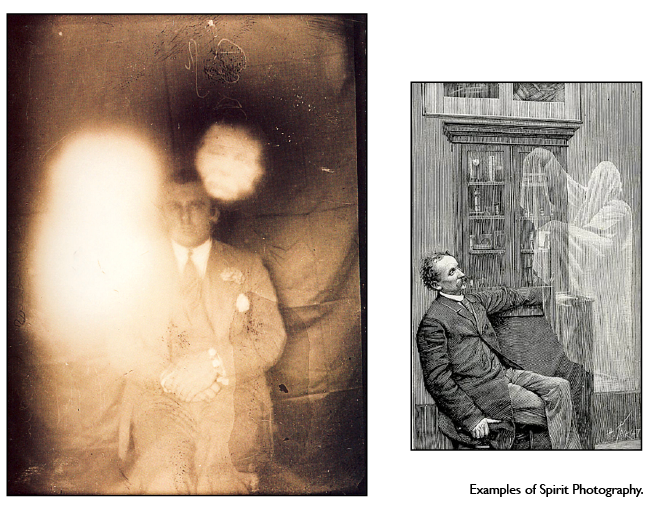

Magicians, especially, were very vocal about perceived fraud perpetrated on the believers at séances, exposing the tricks of mediums. Spirit photography had become another controversial phenomenon, the authenticity of which was always hotly debated. Experts knew very easily how such photos could be faked, but those who believed in them persevered in their faith, as there were always some who decreed them as authentic. In such an atmosphere, one side claiming fraud, the other claiming proof of afterlife existence, these mysteries were never resolved satisfactorily. Doyle, of course, was always convinced that some examples were legitimate and he remained intrigued by it, even publishing on the topic, “The Case For Spirit Photography,” (1923).

In 1920, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini (1874-1926), the great magician and escape artist, met in England and were instantly attracted to each other. Doyle had followed Houdini’s exploits and believed the man had remarkably developed paranormal powers. Houdini probably thought this was naïve and amusing. They each approached the occult from widely different viewpoints, but both were very public personalities, promoting propaganda to sway audiences to their own position. Both had big egos (rightfully earned); both were very biased in their espousal of what they held to be true. It was Spiritist vs. Magician.

Houdini had been seeking verification of an afterlife, in hopes of finding a way to communicate with his beloved departed mother. He had not yet found an answer and was becoming jaded. He truly believed that the art of illusion should be a form of entertainment that audiences willingly attend, ready to temporarily suspend their disbelief, and should not be misused to pacify those who were seeking answers, grieving and desperate. Houdini’s exposure of fraudulent mediums became an obsession that mirrored Doyle’s own, but Doyle’s was the flip-side—his was to promote awareness among those grasping for a belief in an afterlife and convert them to the way of Spiritualism for their own peace, happiness, and growth. During WWI, amazing stories came out of the battlefields—mystical happenings, mass visitation of glowing beings, and unexplained phenomenon—all contributing to the belief that there were unseen forces in the world, which fostered an awareness and acceptance of the paranormal. These stories made the overwhelming grief more bearable and gave tragedy an otherworldly illumination—it was an understandable human emotional response to deadly warfare, forging links among the bereaved. Spiritism taught that these casualties were delivered whole in ethereal form from the nightmare of war to a place clean and sweet and fresh, where they romped free and uninjured, still in their shining youth. Doyle believed this wholeheartedly, and it gave him solace and peace, and he wanted to share that.

In the 1920s, while researchers and magicians were focusing on exposing fraudulent mediums, Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931), the inventor, was hoping to build a device that would breach the divide between the living and the dead, allowing communication between them. He also made a study of the clairvoyant Bert Reese (1851-1926), and had an abiding interest in psychic phenomena and telepathy. Even earlier, in 1902, Edison had filmed a motion picture, Jack and the Beanstalk, called a “fairy play” in its listing at the Library of Congress archive. In 1922, Doyle predicted that radio waves would be able to carry the spirit voices of the dead to loved ones. The implications of Spiritualism were openly debated by some of the eras most intelligent and curious minds, including Italian Criminalist and Psychiatrist Cesare Lombroso, and William James, American psychologist and brother of Henry James. In 1923, Scientific American magazine offered a monetary prize to an authentic medium who could produce a genuine manifestation. It never paid out the money to anyone.

Eventually, modern thought and scientific investigation shifted from communication with the dead to the possibility of determining brain functions and mental powers, like extra sensory perception and thought transference, questioning whether a channeling medium’s output might possibly be the product of the unconscious mind. With the advent of modern electronic devices, even later theories posited the possibility of mental manipulation of cameras and recording devices.

In 1959, F. Jurgenson was recording birds on tape and claimed he heard his dead relatives upon playback. In the years since, many voices in many languages have been caught on tape, but still defy objective deciphering. Some theorize Electronic Voice Phenomena is paranormal activity, or the result of psychokinesis, or even auditory hallucination. Any responsible modern researcher will always make the attempt to verify whatever messages they “capture” on tape, before releasing any determination of the results. Skeptics claim the process is so subjective that any intelligible communication could only be interpreted through wishful thinking.

Rare Mediums

The name of Madame Blavatsky (1831-1891) is the one most commonly associated with the Victorian era of eccentric mediums. Born a Russian, she was married off at a young age to an older man, then abandoned him, resurfacing in New York City in 1873, with wild stories of how she spent the previous years. By 1874, Madame had reinvented herself into a medium. She befriended Col. Henry S. Olcott (1832-1907), and together they authored Isis Unveiled, and established the Theosophical Society. This new religion borrowed from the Cabala, Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, and incorporated Madame’s own quirky theories and doctrines. Some well-known devotees were Thomas Edison, Yates, and Tennyson. The woman herself was described as a chain-smoking mess, but obviously she exhibited great charm and powers of persuasion, and her main precepts promoted the study of comparative religion, the investigation of the occult, the understanding of natural laws, and man’s untested natural powers of the mind. Over 100,000 followers were converted to her cause, which still survives to this day, under the title Theosophy.

Clairvoyants throughout time are thought to have supplemented their supposed innate powers with grandiose exhibitions of phenomena in order to increase interest, which only makes it impossible to prove the underlying truth. Conan Doyle and Houdini may well have understood this unhappy contradiction, being famous showmen themselves. Doyle would believe wholeheartedly, knowing there were bound to be some suspect results, while Houdini was loathe to commit to belief, for fear of being duped publicly, and so spent the latter part of his life debunking mediums, while Doyle enjoyed them. It was the nature of this magician to be skeptical, exposing the “trick” to keep control and maintain order in his life.

Clairvoyants throughout time are thought to have supplemented their supposed innate powers with grandiose exhibitions of phenomena in order to increase interest, which only makes it impossible to prove the underlying truth. Conan Doyle and Houdini may well have understood this unhappy contradiction, being famous showmen themselves. Doyle would believe wholeheartedly, knowing there were bound to be some suspect results, while Houdini was loathe to commit to belief, for fear of being duped publicly, and so spent the latter part of his life debunking mediums, while Doyle enjoyed them. It was the nature of this magician to be skeptical, exposing the “trick” to keep control and maintain order in his life.

In some of the great unsolved crimes of the nineteenth century, mediums, or clairvoyants, insinuated themselves into the case. During the Jack the Ripper murders of 1888 in London, the psychic, Robert James Lees (1849-1931) claimed to have solved the case, pointing to a well-known physician as the murderer. Lees was famous enough to have been consulted by Queen Victoria and Scotland Yard.

Letters from mediums offering to come to Fall River, Massachusetts, if all expenses were paid, were received by Marshal Rufus Hilliard and District Attorney Hosea Knowlton, to solve the murder case of Andrew and Abby Borden in 1892. Communications from the deceased victims were claimed to have been received. One medium explained to a Boston Globe reporter that contacting the murdered Bordens about the crime might not be productive, because they thought Andrew was asleep and Abby’s back was turned when attacked, and therefore neither would have seen their assailant! Of course, both of these Victorian murder cases are still unsolved.

Contact?

The Great Houdini, the most outstanding magician-performer of his day, never faltered in his quest to affirm a genuine communication from his deceased mother. In 1922, an unfortunate misunderstanding arose between Houdini and the Doyles. Lady Doyle was attempting to channel Houdini’s beloved mother, and he had, for once, suspended his disbelief, because he was fond of and trusted the couple. The session left him hurt and frustrated—yet he did not immediately let on. He struggled with the question of when to reveal to the world that the reading had failed, as he did not want to make negative aspersions against the Doyles, but neither did he want to prolong the impression that they had achieved contact. The price of fame was to live through these personal struggles in public, with an eye toward an eventual press release.

Apparently, Jean Doyle received another message at the same time as the controversial contact with Mrs. Weintz. It was a prediction of Houdini’s impending death, at a rather young age. He did die within four years, aged fifty-two, but it is not clear if he knew of the prophecy. It would be very odd to think that while Houdini thought he was protecting the Doyle’s reputation, they might have been protecting him from an uncomfortable prognostication about his impending doom. Of course, a famous medium in 1928, Arthur Ford, through his guide “Fletcher,” supposedly broke the code that Houdini and his widow, Beatrice, had agreed upon before his demise, which she acknowledged. And also, of course, to follow the pattern, she later denied it.

During their lifetimes, the friendship between Doyle and Houdini weathered all of the storms of controversy. They continued to hold each other in high regard, as if each was star-struck over the other. They were an amazing duo to see walking along the shore at Atlantic City, two of the most famous men of popular culture of their day, joined as friendly adversaries in the exciting investigation of the occult.

During Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s memorial service, on 13 July 1930, in Albert Hall, medium Estelle Roberts claimed he was in attendance and proceeded to transmit Doyle’s communication to his widow. From then on, clairvoyants around the world published messages purportedly from Doyle, as if he were now the newest easy pipeline to the afterlife. Once Jean died, revelations were made of her supposed messages to the remaining family as well—and so it goes. The Dead Celebrity was a convenient conduit for any bargain psychic to lay claim. Sir Arthur probably would not have minded the exploitation—he was tolerant of whatever a medium had to do in order to pass on their true message of the personality’s survival beyond death.

The Message in the Medium

In times such as these, as the pattern of historical turmoil repeats, with television news fixated on war and natural disaster, world terrorism, and stock market casualties, we are re-experiencing the retreat from reality into fantasy. Television shows on the supernatural have proliferated our modern culture and those programs featuring a psychic medium are again most popular: John Edward’s Cross Country; Lisa Williams’ Life Among the Dead; Derek Acorah’s Ghost Town; Sylvia Browne on Montel; James Van Praagh as consultant on Ghost Whisperer; and Alisson DuBois consulting on Medium—most have also authored books on the subject. We should keep an eye out for those two very real young girls who can play havoc with history.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle would fit rather well into twenty-first century society. His reflections on fairies—that the only thing separating us from them is a difference in our vibrations—was possibly prophetic. Recent hypothesis by great minds on the subjects of life, matter, energy, light, the solar system, and the universe, produced the Theory of Relativity and then its companion Quantum Mechanics, after which came String Theory, and its new compliment, Membrane Theory—which postulates that there are multi-dimensions within multiple universes. One could thus argue that the energy of the soul survives death, in a state where there is no time, in another dimension. Where the membranes of these worlds connect with ours, we can perceive them as spectral, and thus interact.

To a person with such a sincere belief in an afterlife, and one whose character was defined by courage in the face of the unknown, as an attribute of any explorer, Sir Arthur probably greeted his passing with a sense of anticipation. There will always be a time, in the ebb and flow of the history of human beings on this earth, when scared and worried minds will reach out for comfort and succor to their deceased ancestors, begging for relief from grief, or just a simple answer to the question: “What’s next?”

Works Cited:

Doyle, Arthur Conan. The Wanderings of a Spiritualist. NY: George H. Doran Company, 1921.

Edison, Thomas A. Jack and the Beanstalk, A Fairy Play, early motion picture, Library of Congress, 1902.

Gettings, Fred. Ghosts in Photographs, The Extraordinary Story of Spirit Photography. NY: Harmony Books, 1978.

Kent, David. Lizzie Borden Sourcebook. Boston: Brandon Publishing, 1992.