by Shelley Dziedzic

First published in Spring, 2009, Volume 6, Issue 1, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

One could argue with some measure of success that the Victorians surely rivaled the Ancient Egyptians with their all-consuming concerns with Death and the protocol and ceremony surrounding departure from earthly life. A veritable death industry reached its apex in the interval of 1850-1880, with the suppliers of mourning accoutrements, from makers of hair jewelry to sentimental and highly romanticized funeral statuary, carving out a lucrative niche. Some may point to the tragic 1861 death of Prince Albert, the popular consort of Queen Victoria, and her morbid reaction to it, as a major factor in the evolution of funeral practices and mourning.

America took her cues from the funeral observances across the Great Pond, where England set the gold standard for funerary excesses. Death was truly celebrated with as much pomp and enthusiasm as birth and matrimony, and Death was a frequent caller for both young and old. Professional mourners, wandsmen, mutes, and “pleurants” could be hired to march behind the hearse for a fee, weeping and wailing all the way to the cemetery. The hearse itself, a confection of gilded black festooned with bunting, a glass window showcasing the coffin, and pulled through the streets by six black-plumed steeds, was a sight to stop traffic. This ostentatious display of grief was considered the correct way to illustrate to those still above the ground that the deceased was truly mourned and missed by the family left behind. Families would go into debt to furnish the Dearly Departed with as fine and extravagant a send-off as money could buy. Funeral Clubs sprang up, whereby the middle class and poor might put aside funds for their own final journey to the churchyard.

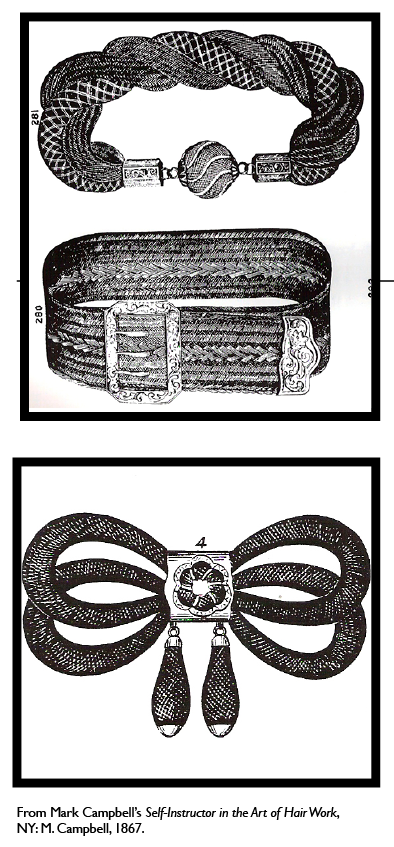

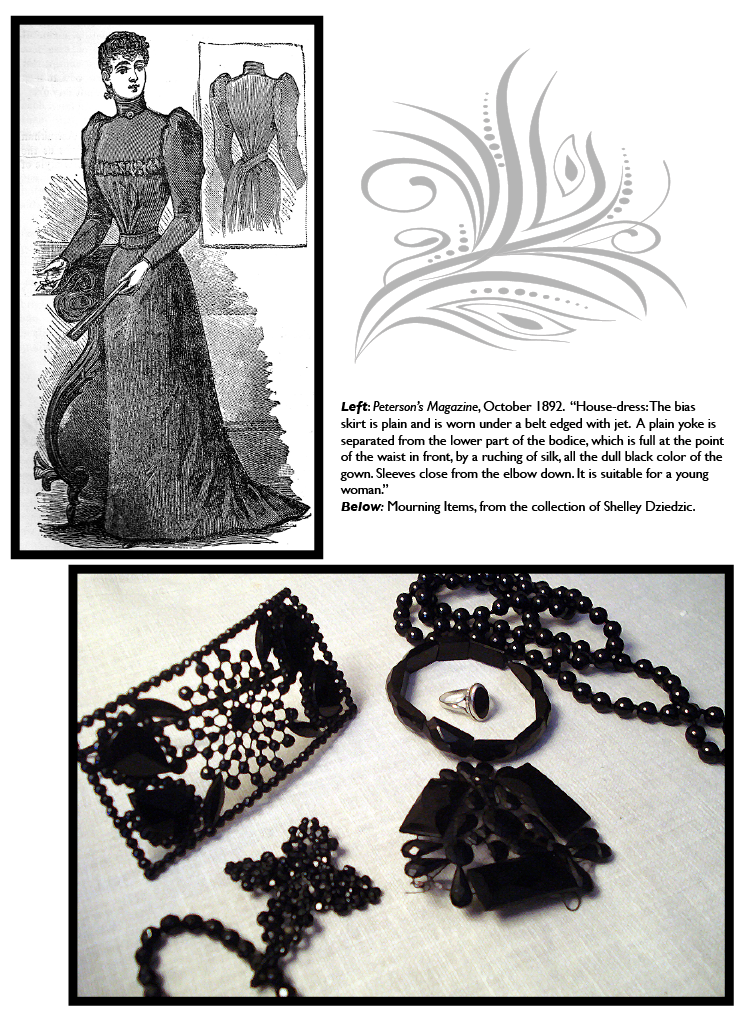

Not only were the funerals and wakes themselves over-the-top excesses of lugubrious splendor, the family was expected to continue the gloomy and melancholy appearance long after the deceased was cold in the tomb by secluding themselves from society functions and draping themselves in dull black mourning attire. The time set aside for these observances depended upon the relationship to the deceased. A widow was obliged to wear deep mourning for the first six months, which was comprised of lusterless dull black and crape-trimmed bonnets. Second mourning might allow for black with a sheen to the fabric, jet jewelry, or bog oak, vulcanite, onyx, or gutta percha jewelry with tiny seed pearls that symbolized fallen tears. Locks of hair from the Dearly Departed were woven into astounding pieces of jewelry for both men and women, and rings, bracelets, lockets, earrings, and all manner of framed artwork made of human hair could be found in the parlors across America.

Not only were the funerals and wakes themselves over-the-top excesses of lugubrious splendor, the family was expected to continue the gloomy and melancholy appearance long after the deceased was cold in the tomb by secluding themselves from society functions and draping themselves in dull black mourning attire. The time set aside for these observances depended upon the relationship to the deceased. A widow was obliged to wear deep mourning for the first six months, which was comprised of lusterless dull black and crape-trimmed bonnets. Second mourning might allow for black with a sheen to the fabric, jet jewelry, or bog oak, vulcanite, onyx, or gutta percha jewelry with tiny seed pearls that symbolized fallen tears. Locks of hair from the Dearly Departed were woven into astounding pieces of jewelry for both men and women, and rings, bracelets, lockets, earrings, and all manner of framed artwork made of human hair could be found in the parlors across America.

Always looking for ways to memorialize the Beloved Dead, family mourners set up permanent tributes, the work of their industrious hands, in the form of post mortem photograph displays, hair work jewelry and wreaths, embroidered sentiments on perforated paper, glass domes heaped with waxed funeral flowers, even a decorated vacant chair solemnly allotted to the Loved One who would live on in spirit and hearts forever in the home. The Victorians were abundantly sentimental in many aspects of daily life, so it comes as no surprise that death would receive the same tender consideration.

The Victorian home was awash with small, beautifully bound volumes of poetry on death, immortality, and heaven, just as were the walls awash with colorful lithographs of angelic children being tenderly lead through the gates of heaven by kindly angels, lovely maidens in white, and tragic widows in black gazing wistfully at departed husbands. Most artistic renderings had poignant titles such as “Remembering Father,” “Going Home,” “At Rest,” and other soothing ways to make the transition from life to death less fearful. The music rack on the parlor piano was not neglected either and many songs of the “tear jerker” variety would be played and sung in tearful tones. The melodies and lyrics sound maudlin today, but in the Victorian era through World War I, this type of song was performed with great seriousness and pathos. “When the Grass Grows Over Me,” “There’s a Picture Draped in Mourning,” “Mine is the Mourning Heart,” “Where My Mother Sleeps,” are but a very few among hundreds of sad songs which enjoyed wide popularity, especially during the Great War. The Victorians were great churchgoers as well, and were much comforted by the old familiar hymns that offered the prospect of the sweet bye and bye where all would be reunited once again.

The Victorians were also believers in extending their sentimentality and romanticized view of death and the hereafter outside the home and into the cemetery. Mount Auburn, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was America’s first garden memorial park, founded in 1831. Kensal Green and Highgate, two of the original “Magnificent Seven” garden-style cemeteries of England, built in the period between 1832-1841, shared the vision of a beautiful, park-like setting of plantings, fine architecture, and statuary. Fall River’s Oak Grove Cemetery soon followed suit in 1855. The symbolism associated with Victorian funeral statuary abounds at every turn in these Cities of the Silent. The language of flowers, as well as many symbols of the virtues, linger on today in marble and granite as hidden messages for all to decipher.

By 1892, the trend toward excess in funeral ceremony had begun to wane. Expectations as to dress and behavior after the loss of a relative, however, still followed the conservative etiquette of earlier decades. A most telling comment, made in the local papers about Miss Lizzie Borden’s appearance on the day of her parents’ funeral was that she was not in mourning. She did, however, wear a form-fitting black lace dress and a hat of somber hue. Mourning for a parent at this time might have constituted veiling, and the wearing of some dark crape fabric. The many reporters and ladies who attended her trial duly noted Lizzie’s appearance, and they remarked on her dress at every sighting from the train station to the courthouse. It was daring for Lizzie to be seen in a color other than black, and most extraordinary that she might wear bright cherry-colored ribbons on a black hat before the year’s interim of her parents’ death had passed, as Victoria Lincoln claimed in her book, A Private Disgrace.

Naturally, the circumstances of Andrew and Abby Borden’s deaths could hardly be said to be typical, and thus the scrutiny surrounding the funeral and the behavior of their daughters and extended family was unusually focused. Most Victorians were born, often married, and died at home. The wake, viewing, and services were generally conducted from the home parlor, or in the case of a prominent individual, the church, where the coffin would have been opened for the guests to pay last respects. On the morning of the Borden funeral, Saturday, 6 August 1892, at 11:00 a.m., up to forty neighbors and relatives crowded into the small house on Second Street to hear the prayers given by Dr. Adams and Reverend Buck. The immediate family would have said private farewells before the guests were admitted. It was customary to elect a neighbor or close friend to take charge of meeting and greeting guests and assisting with arrangements as the immediate family members, especially the ladies, would be in too fragile a state of grief to attend to such public commitments. Alice Russell, former neighbor and close friend of Lizzie and Emma Borden, may well have served in this capacity, although Lizzie herself expressed her preference for James Winward to take charge of the preparation of the bodies.

In spite of the shocking wounds of the deceased, the coffins were open for viewing, with the intact portions of both murder victims being faced outward. The coffins, in the traditional European shape of a wide top and narrower bottom (so as to follow the natural shape of a human form, thereby saving wood) were probably of cedar, covered with black broadcloth, with three silver-plated handles on each side and a name plate on the lid. The Fall River Evening News notes that Andrew’s coffin bore a wreath of ivy and Abby’s a wreath of white roses and sweet peas tied up with fern and white satin ribbon. According to The Household Encyclopedia, ivy, in the language of flowers, stands for marriage and fidelity. Often a married couple’s side-by-side graves will be twined around with ivy plantings. The white roses signified I am worthy of you and sweet peas simple pleasures with fern having the meaning of sincerity. Flower shops catering to the funeral trade abounded by 1892, so there is no way to know with certainty if the flowers chosen were of any deliberate significance, although pale flowers, especially white, were in great vogue and the displays were usually very large and showy. Photographs and even stereopticon photo cards were frequently made of floral tributes for both the famous and not-so-famous funerals. The mills and banks with which Andrew Borden was affiliated no doubt sent floral baskets and wreaths to the grave. It is likely that thick black or white cardboard mourning cards were printed up with some verse and the dates of the deceased engraved, and the Borden sisters would have observed the custom of black-bordered stationery and handkerchiefs for a year.

As the funeral party left #92 on its way to Oak Grove, the hearse carriages, containing the two coffins would have gone first, followed by the carriage of the undertaker and pall bearers, then the family, followed by friends and neighbors. Emma and Lizzie would ride in the procession to the cemetery, arriving at 12:20, but would not descend and follow the minister and their uncle, John Morse, to the graveside for the final prayers, which lasted perhaps only two minutes. This was not expected of Victorian ladies, as it was judged too taxing on their fragile feminine constitutions to be confronted with the yawning open grave. The graves themselves were lined with dark, thin cloth and strewn with evergreen fir branches, a common practice before the advent of grave vaults. The viewing of raw earth was too grim a reminder of the phrase, “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.”

All along the cortege route, hundreds of Fall River citizens lined Second Street and were waiting with interest to view the spectacle at the cemetery. The procession turned left on Borden Street and made a pass by the Andrew J. Borden Building on South Main before continuing up to North Main Street, bearing right onto Cherry Street, then left onto Rock Street, and northward to Prospect Street where the procession went east into the main gate of Oak Grove. The custom of passing by the place of business of the head of house is still carried on today, if it is logistically possible. The procession then passed beneath the great granite Gothic arch, which had been erected in 1873, emblazoned with the motto, “The shadows have fallen and they wait for the day”—an apt sentiment considering the circumstances of the Borden murders. The deceased pair were to have no rest on the day, however, as after the graveside service, they were promptly removed to a holding tomb to await further developments and a more thorough autopsy in the Ladies’ Waiting Room near the front entry, which occurred the following Thursday, 11 August. It was there that the skulls were unceremoniously removed and retained for trial evidence, unbeknownst to the Borden sisters.

After the acquittal of Lizzie Borden, she and her sister selected a conventional and conservative family marker, made of famous Westerly, Rhode Island, blue granite, which was installed on the Borden plot in January of 1895. Andrew Borden is buried between his first and second wives, a custom common to New England. Eventually the skulls, which had been removed, were buried in small containers behind the small rectangular headstones, above the coffins, but not at the same depth. Ground-penetrating radar scans were carried out by Professor James Starrs of George Washington University in 1992. In March of 2009, Starrs reported that those scans reveal that the lid of Andrew Borden’s coffins appears to have caved in. Small anomalies indicate the probable location of the skull containers beneath the sod.

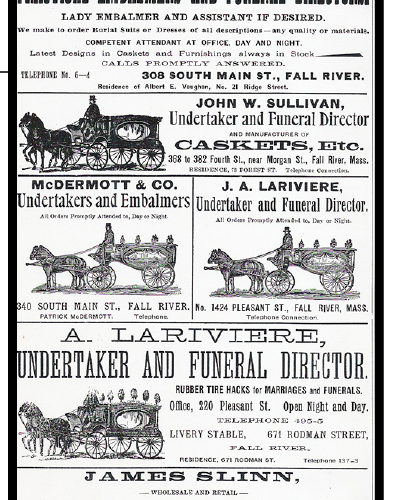

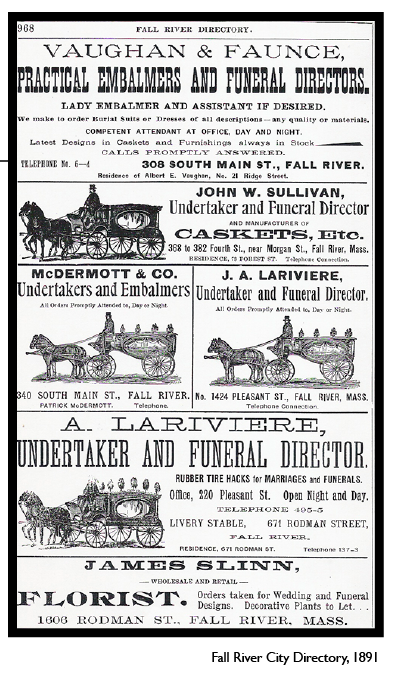

It was desirable and seemly, to the Victorian way of thinking, that the mortal remains of the deceased should eventually return to the earth through decomposition. The art of embalming was being perfected during the Civil War, when the necessity for preserving the bodies of dead soldiers required a method of preserving the remains for a period of time, allowing for transport home. Dr. Thomas Holmes of Brooklyn, New York, is generally credited as the “Father of Modern Embalming.” Dr. Holmes is credited with the embalming of 4,028 Civil War officers and soldiers. Various combinations of mixtures containing alcohol, arsenic, creosote, mercury, and turpentine were used as embalming fluid prior to 1866, as formaldehyde was not discovered until after the end of the war. Mr. James Winward, Lizzie Borden’s undertaker of choice, with his assistant, prepared the bodies of Abby and Andrew Borden in the home on Second Street, in the dining room. Portable tables, called cooling boards, were brought to the home for the preparation of the corpses. The preparation of the Bordens probably included embalming, after the stomachs of both Bordens were removed and sent to Prof. Dr. Wood at the Harvard Medical School for examination. Mr. Winward was, as many undertakers were, including Andrew Borden himself, both an undertaker and a dealer in furnishings, and maintained a “wareroom.” Andrew Borden had supplied items for funerals, and as a carpenter, most likely made coffins—but was not himself an embalmer or mortician. Later on, “funeral director” and “funeral homes or parlors” would enter the American vernacular, as the need for larger spaces to accommodate viewings were required. The improvements in the highway infrastructure and railroad routes enabled a greater mobility to the population to attend funerals of family and friends.

By 1927, the year of both Lizzie and Emma Borden’s deaths, the Victorian views on funerals and mourning behavior had drastically altered. The staggering numbers of World War I casualties had influenced the way the dead were buried and mourned. Gone were the regulations for wearing black mourning clothes for a prolonged period, and the rigorous rules of isolation from society. Widows might wear somber colors for a short interval, and the black armband or hatband was still often observed for men mourning a loss in the immediate family. Lizzie’s own written instructions for her funeral indicate a wish for privacy, as Lizzie Borden undoubtedly knew, that even by 1927, her name was synonymous with notoriety—to the point she adopted Lizbeth as her new first name.

Her wish to be buried at her “father’s feet” reflects a certain Victorian sentimentality, that of the adoring daughter, or perhaps, if one believes her to be guilty of the crimes, a penitent criminal! Her wish that only her faithful household staff and closest intimates be a part of the proceedings is understandable, as is her wish for the minister, Rev. Cleveland of the Ascension Episcopal Church, to preside at the prayer service. It has been said that Lizzie Borden had been heartlessly snubbed at her Central Congregational Church on Rock Street after her acquittal, and did not return there again. Lizzie’s cousin and good friend, Grace Hartley Howe, was also a member of the Church of the Ascension, which may also have had some bearing on Lizzie’s choice. Lizzie’s scripture choices were interesting and worth studying. Tennyson’s “Crossing the Bar” was a favorite of the times, with the line “And may there be no moaning of the bar when I put out to sea” perhaps reflected a deep desire to pass without notice and fanfare in the Press and within the confines of Fall River. If so, that would prove to be wishful thinking.

Perhaps the strangest direction Lizzie gave was to have her grave “bricked over”—a practice which resulted from the terrible era of grave robbing or body snatching, by the so-called “Resurrection Men,” who pillaged the graves of the recently buried for fresh corpses to sell to medical schools. Grave robbing was a practice of the early nineteenth century in Britain, an example being the famous Burke and Hare case in 1828. By the late 1890s, body snatching was rare and, by the next century, had all but disappeared in America and Great Britain. It is still possible to see iron cages built over the ground, called “mort-safes,” in some Victorian era cemeteries. Whether Lizzie feared being disinterred, or having her remains unearthed by animals, is unknown—perhaps she merely wanted to insure absolute privacy below the ground for eternity, as she valued it above the ground. Did Lizzie leave a message in her choice of final hymn, “My Ain Countrie”? The answer to that, as with many other questions, Miss Borden would take with her to the grave.

Works Cited:

Campbell, Mark. Self-Instructor in the Art of Hair Work. NY: M. Campbell, 1867.

Coleman, Penny. Corpses, Coffins, and Crypts, A History of Burial. NY: Henry Holt, 1997.

Curl, James. The Victorian Celebration of Death. England: Sutton Publishing, 2000.

Fall River City Directory, 1891.

Lincoln, Victoria. A Private Disgrace: Lizzie Borden by Daylight. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1967. Rpt. NY: International Polygonics, 1986.

Northrop, Henry Davenport. The Household Encyclopedia. Boston: Bay State Company, 1890.

Peterson’s Magazine. Philadelphia, PA: Charles J. Peterson Publishing, October 1892.

Rebello, Leonard. Lizzie Borden: Past and Present. Al-Zach Press, 1999.

Starrs, James. E-mail correspondence with Shelley Dziedzic. 27 March 2009.

Ward, Lee. Coffins, Kits and More: Stories of the Civil War Embalmer. MI: Two Trails Publishing, 2007.