by Kat Koorey

First published in May/June, 2006, Volume 3, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

Very early, on an August morning in 1892, on what would become one of the most infamous days in the history of Fall River, two men sat talking over breakfast. They were brothers-in-law, although bereft of the woman who had tied the two together legally. They shared similar backgrounds and views on financial matters, and the subject was broached about a millionaire’s yacht now up for sale for $200,000. The yacht belonged to Jay Gould, who was dying. It was an ironic conversation, if it really did take place, because the price of the yacht would have cost one of them 1/2 of his own fortune and he would not be able to maintain it. “What little good would it do me if I really did have it?” asked Andrew Borden of John Morse.

What good it might have done him would be to probably save his life. If only Andrew had loosened his purse strings a bit more and lived in the style more commensurate with his wealth and standing. It certainly would have pleased his daughters who would have liked to benefit from a more generous lifestyle. Newspapers were full of stories of tycoons such as Astor, Morgan, Rockefeller and Vanderbilt. Andrew Borden was not in their same stratosphere, but he was cut from similar cloth, and had he lived, might have made it into the millionaire club.

In the late 1800s, William H. Vanderbilt was the richest man in the world. His was inherited wealth, but during his lifetime, he greatly enlarged that fortune. His father, Cornelius Vanderbilt (the “Commodore”), had confidently left him in charge of his business holdings knowing that his son was as ruthless as he.

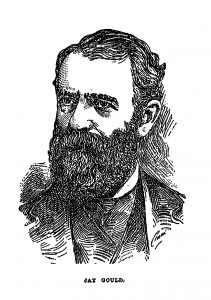

Ruthlessness was a key ingredient in amassing the kind of fortune not yet known in the Western world, and crushing one’s opponent was a desirable outcome. Jay Gould, who rose from being a farmer’s son to a place of highest prominence in the world of American finance and business, had that same spark of single-minded ruthlessness. When he was older and savvy enough to play with the big boys, it would be a clash of the Titans.

Commodore Vanderbilt was considered among the Robber Barons of American history—those entrepreneurs who spent the 1850s and 60s creating and then looting big businesses before there were rules against such things. They then spent the 1880s and early 90s in the conspicuous consumption of leisure and luxury, and the newspaper reading public was fascinated by their lifestyles. Some stories were bold and nearly libelous rumor and innuendo. However, the driving force behind such giants as Commodore Vanderbilt and Jay Gould was never quite understood in their own time. Some historians speculated that only in the future (now) could their methods and motivations ever be truly understood or revealed.

The inevitability of the clashing career paths was partly because old Cornelius Vanderbilt and the younger Jay Gould shared the same birthday, May 27, and had many traits in common. They employed questionable business tactics, learned on the fly as they made their own rules, and cared little about the public’s perception of them. Both men died leaving little to charity, inspiring censure in the papers. Cornelius had been convinced to endow a university to be named after him with one million dollars upon his death in 1877, but that was a pittance compared with his fortune of 100 million and was barely mentioned to his credit when he passed. When Jay Gould died in 1892, it was estimated he was in possession of between 150 million and 200 million dollars. He left a structured will that provided only for his family.

On a smaller scale, Andrew Borden might be compared to these men as a symbol of the times—all three men were judged after death as being purely dedicated to money getting for its own sake, and uncaring as to how they accumulated their profits. It is probable that Andrew Borden did not even have any fun in the making of his money—to him it was serious business—whereas the Titans were consumed and invigorated by the process.

It was written about Jay Gould (as about Andrew Borden) that he preferred to live simply and that he did not care to make any conspicuous display of his wealth. It was said that he was no philanthropist, but when his children had a need, he provided them with the wherewithal. In his later years, Gould was described as sour and a bit vindictive from years of critical commentary on his business methods and lifestyle.1

Gould had started from nothing, an unknown entity with unknowable potential, and rose high in the sphere of finance on his own wits and self taught business acumen. When Gould died, the Boston Globe published an article entitled “Millionaires and Public Opinion.” In some part, and considering a lesser fortune, this article could also be an assessment of Andrew Borden’s character:

Jay Gould left no money for charitable purposes, and made no atonement for a life of overreaching by humane and generous legacies in his will.

Nor had the public any right to suppose that he would be so inconsistent in his death as to make provisions for objects which never interested him during his life.

He was one who amassed fortune simply for the degrading and unworthy love of wealth. He didn’t accumulate money as a means of accomplishing great purposes. The money itself was its own end. He had no higher object in view, and so was merely a miser on a gigantic scale . . . Millionaire stinginess should be made enormously unpopular. It may be hard to teach old millionaires new tricks. But when a great millionaire like Jay Gould dies, he usually leaves several smaller millionaires behind him as his successors. These younger money kings who inherit this wealth should be more susceptible to public opinion then the old and hardened predecessor by whom it was transmitted to them. This very thing has happened with some of the members of the Vanderbilt family. It is not utterly impossible that a generous disposition may be developed even in the Gould family.2

When comparing the half-millionaire Andrew Borden to the multi-millionaires of his day, they all sound as if they went to the same school of business and subscribed to the same rules of money-getting: You obtain it and you keep it and that’s the foremost way to acquire more. These men raised themselves up in the early 1800s: Cornelius Vanderbilt was born in 1794 and died in 1877; Andrew Borden was born in 1822 and died in 1892; and Jay Gould was born in 1836 and died in 1892, of consumption.

There is obviously a connecting theme in the way these men created opportunities for themselves where there had been none there for lesser men who had not their foresight. They were careful with their fortunes later in life, after the early days of wild speculation, and guarded them like sentinels. It was up to the discretion of the next generation to play the philanthropist.

These old Robber Barons were a product of their times, and their children (like Emma and Lizzie Borden to a lesser degree) would eventually distribute some of the wealth to benefit their communities—as probably influenced by the times they lived in.

Jay Gould was described upon his death by the Atlanta Constitution as one who enjoyed the study of history and biography, and “his library was filled with valuable books, and he was proud of them. He had a passion for flowers [orchids] and his conservatories were among the finest in the country. The beauty of nature or of art always impressed him . . . and at a feast ate daintily like a bird, and never sipped more than a spoonful of light wine.”3

In comparison, they continued, “The ordinary rich man, worth say a few hundred thousand dollars, sometimes wonders why he does not accomplish greater things in the line of money making. Nine times out of ten the reason is because he can talk nothing but ‘shop.’ He knows nothing of literature and art—nothing of science—nothing of politics in its larger sense. So he is shut out from the friendship of the superior intellects of his generation—men who would advance his interests if they found him congenial. He is left to consort with his business associates of the same caliber, or such society as his bank account draws around him.”4 This sounds like the lament of Andrew Borden’s daughters, in that their father only cared for simple things, and, consequently, his vision was too narrow to allow his daughters to take a place in society.

The names Vanderbilt, Gould and Astor bring to mind images of huge mansions in New York City, Newport and New York State—as well as of huge steamer yachts. Even though Gould was described as one who liked to live simply, there was always a social position to maintain, and so there necessarily had to be a 5th Avenue address and an estate in the country. The steamer yacht was an expensive toy and yet a practical means of conveyance—with engines one could arrive on time, which was a huge advantage to a businessman.

Yachts, however, beget races, and the regattas of Newport were spectacular affairs. It would have been easy to get caught up in the racing scene as a pleasurable distraction. The large yachts were expensive to build, crew, provision and maintain. There was always a competition to have a bigger, better, faster steam yacht.

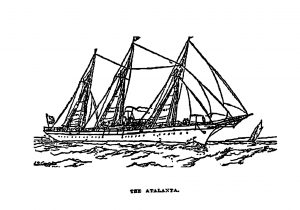

The Commodore commissioned a steam yacht in 1853 and christened it North Star. In 1883, Jay Gould launched his yacht Atalanta (meaning “balanced”), named after the Greek mythological huntress and fleet-footed runner who made a deal with her father that she would race any suitor for her hand in marriage, and if he lost, she not only did not have to marry him, he would also be executed. She not only vanquished all competitors but they also lost their lives. Some might compare the myth to the man, Jay Gould, and find parallels.

It was said that Jay Gould built his yacht primarily for luxury, comfort and safety on ocean voyages, but in an age of racing fever, he was game to test her speed. His yacht competed and won. The Vanderbilts’ lusted after speed and built their boats with that in mind.

In 1883, the Atlanta Constitution ran an item entitled “Jay Gould’s Yacht,” describing his vessel:

Mr. Gould’s stateroom, with its Persian carpets, pink satin couch and rosewood cabinets, is as pretty as the boudoir of a princess. Judging by the preparations today, the guests who are to enjoy the hospitality of the Atalanta will live in scarcely less sumptuous and sensuous quarters than her owner. Turkish rugs and damask hangings, each of a different color to match the hues of the polished carved wood of each room, were unpacked this morning.

Solid silver mugs, pictures and soap dishes, gold-lined and bearing the Gould monogram, were provided for all the staterooms.

Guest Rooms In Colored Satin

The guest rooms on board the yacht are not numbered but are distinguished by the color of the satin which adorns them. There are, among others, the gray, the blue, the brown and the old gold staterooms, the colors of the handsome wood carving in each case harmonizing with that of the draperies. Each room has a miniature cabinet, a wardrobe, a writing desk and a washstand, while four of the longer ones may be turned into luxurious bath rooms as soon as their occupant is out of bed.

Electric Illumination

Edison electric lights, with crystal shades, illuminate the yacht above and below decks. It was evidently the builder’s intention that even at night the delicate carving and splendid upholstering should be seen at their best.

Aladdin Like Delusions

What appears at first to be a solid wall at the end of Mr. Gould’s private staterooms gives way under the touch and reveals a capacious wardrobe. The counterpart of this panel on the left opens by a gentle spring into a bathroom of ample proportions.

It would be difficult to describe the wonder and surprise visible on Mr. Gould’s face as he explored the mysteries of his own yacht for the first time today . . . He was received by Captain Shackford and eighteen seamen in blue shirts with ‘Atalanta’ across their chests.5

Atlanta’s newspaper readers were very interested in these millionaire’s yachts and a month later, the Constitution continued the theme by printing an article titled “Rich Men Afloat.” This piece claimed that the old symbol of fine horseflesh as a possession of the wealthy was being replaced with a new one: the yacht. Once Gould’s yacht had been floated, William B. Astor wanted a finer one, and it was claimed that William H. Vanderbilt (1821-1885), was about to commission “a pleasure steamer of great proportions and unprecedently luxurious appointments . . . He likes to have such things as other millionaires enjoy.”6

Jay Gould had already been in competition in the business world with old Cornelius Vanderbilt and bested him over ownership of the Erie Rail Road (1867-1868), and had fought with William H. Vanderbilt over the Western Union Telegraph Co., years after his father’s death. William H. inherited a rivalry with Jay Gould, along with his father’s millions. In fact, William’s son, William Kissam Vanderbilt (1849-1920), also competed with Jay Gould when he launched a bigger boat, the Alva in 1887. Jay Gould’s career as a Titan had overlapped and clashed with three generations of Vanderbilts, although he himself only lived to age 56.

The yachting racing blood in the Vanderbilts was honestly earned, however, as the Commodore had started out in the ferry business shipping freight and passengers from Staten Island to Manhattan in the very early 1800s. By 1830, he had gained control of the ferry lines and expanded to the Hudson River, eventually controlling trade up and down the New England coastline, before he switched his interest to the railroads.

William K. Vanderbilt’s son Harold (1884-1970), great grandson of the Commodore, actually perfected this familial yachting craze to an art and defended successfully The America’s Cup three times. In fact, during one of these wins, his wife, Gertrude, with her husband, was the first woman to sail in that competition. Harold Vanderbilt’s other claim to fame was as the inventor of the modern American form of contract bridge, which he introduced to his friends whilst (what else?) cruising through the Panama Canal in 1925.

In 1887, William K. floated the Alva, named after his wife. At the time, the Alva was the largest steam yacht built, costing an estimated $500,000. Gould’s yacht was 228 feet whereas the Alva was 285 feet, 57 feet longer. There were only 75 steam yachts in America over 100 feet in length, and these could run all day during an ocean voyage at 15 knots. It was said the cost to the owner of the Alva was upwards of $1200 a month to take an ocean voyage, not including provisions for entertaining or daily meals.7 It is possible that the Atalanta and the Alva cost $200 a day to run. For us to effectively consider the worth of a dollar in the late 1880s, one multiplies the figure by 18: that is $3,600 a day to entertain guests on a day’s sailing outing. In today’s dollars, the yearly cost of these mammoth vessels was around $180,000, which would include wages, upkeep, uniforms, coal, laying up out of season and putting back into commission.

The Alva was designed by St. Clare J. Byrne of Liverpool and was not considered as attractive as Astor’s Nourmahal. She was described as having a bow that was “unusually sharp and narrow, while her stern is said to be very ungainly. It is thought she will roll badly in a heavy sea . . . [but] Danger of sinking from collision is averted by dividing the vessel into four airtight compartments. The Holefern electric search light is in position, and will light up the sea for a distance of eight miles.”8

The Alva was launched at Wilmington, Delaware on October 14, 1886, a steel steam oceangoing yacht, and touted as the largest and the fastest of the pleasure crafts of the world. It would hold 275 tons of coal and carry 28 tons of water in tanks. It had its own small boats that it carried: a cedar steam launch, a harbor gig, a cutter, a pinnace (scout) and a dingy. The Alva boasted electricity on board from a Siemans dynamo and engine housed in the engine room. The signal lights had an electrical attachment when needed. There were also oil lamps for ambiance. It was thought the most excellent feature of the ship was its 4-bladed 10,000 lb. screw made of solid cast manganese bronze.9

When at sea, vessels the size of the Alva would carry “a complete crew with first and second mates, first and second engineers, double sets of oilers, stokers, deck hands, assistant cooks, [and] numerous stewards.”10 The Alva was considered a floating palace, being described as providing as much comfort as home. It had a 31 x 18 foot dining room, a library, and ten suites that included a bedroom, sitting room, chamber room and bathroom. It also had another unique luxury feature: a common nursery for any visiting children and their governesses.

By comparison, the sloop yacht Mabel F. Swift, owned by C.W. Anthony, was a smaller racer, her class being in the 30 to 50 foot range—50 feet being approximately the size of the difference between Gould and Vanderbilt’s yachts. Lizzie Borden was mentioned in the Fall River Evening News, nine days before the murders, as being one of a party of ladies from Fall River who were “stopping at Blake’s Point” while the sloop yacht Swift was at Marion.11

In 1888, the Swift and her owner, Anthony, were mentioned in the Boston Globe:

It was a jolly throng of New York yachtsmen that gathered in the New Bedford Yacht Club house tonight, to enjoy the music and other good things provided by their local friends . . . among others present . . . C.W. Anthony of the sloop Mabel F. Swift . . . Mr. Camancho amused the boys with some good old songs and Commodore Dickerson sang ‘Reuben Kanzo’ til the maintopsail was mastheaded, when all hands shouted ‘Belay.’ 12

Such descriptions of the after-hours yachting scene are so atmospheric they fire the imagination. One can almost hear an accordion, see the fire flickering in the grate, smell the cigars and whiskey, and hear the crude words sung out in unity and laughter.

Another mention of the sloop appeared in 1894, in an article titled “Sport at Fall River, Yacht Club of That City Sailed a Regatta of Seven Classes,” where she won a race:

The greatest general interest centered in the contest between the sloops of the first and second classes. The former was for the challenge cup. The Swift captured it last year [1893] and the Chapequert, owned by C. H. Jones of Boston, carried it off in the regatta of 1892. The Swift will hold the trophy for the coming year, having outfooted her rival today, winning by eight minutes.13

It took a little under 2 ½ hours to run the course. Whether the regatta was out of Fall River, New York, or Newport, and regardless of the class of ship racing, it must have been an exhilarating afternoon for spectators: flags flying, brisk salt air, colorful costumes and finery, triumphant shouts, the thrill of a race, maybe a little betting on the side, and being a part of an old seafaring tradition. Anyone—boat owner or mill worker—would certainly enjoy a day out such as that!

In 1896, there was unfortunate news. “The Mabel F. Swift broke her gaff during the afternoon while off Cat Island, and the cutter Rodina broke her topmast,” on a day described as a “fine one for yachtsmen, as it was clear, with a light southwesterly breeze in the morning, which strengthened during the day [out of Marblehead] so that many of the yachts had to reef.”14

Three days before Lizzie Borden visited at Blake’s Point with her friends, on July 24, 1892, the pride of William K. Vanderbilt, the still new, still splendid, “largest and finest pleasure craft in the world” (as quoted in 1886), was smashed into by the freight steamer H.F. Dimock of the Metropolitan line and sunk in a dense fog. A half-million dollar gargantuan steam yacht with rich appointments became, very quickly, a hunk of junk, lying 5 fathoms down off Nantucket shoals.

It had been a hot, close night and Mr. Vanderbilt and his guests had stayed on deck after midnight for the cooler conditions in the open. They retired to bed late and were awakened so suddenly around 8 AM that no guest on board knew quite what had happened. As they struggled to the deck to evacuate, no men had on trousers or coat and were lucky if they had tied off a light silk robe, as had Mr. Vanderbilt, before appearing in public. Once Mr. Vanderbilt, his family and friends were removed from the now rapidly sinking ship, they were given assistance by the Dimock, came aboard her, and clothing was found to accommodate them. Nothing was saved in the way of possessions, so quickly did the Alva fill with water. 52 crewmen went over the side, and just as the mate, steward and Captain stepped off the deck as the last to go, she keeled over on her side, and from crash to sinking it was fifteen minutes and she was gone. She settled down under thirty feet of water, but her funnel and masts still showed. She had been hit forward on the port bow and cut all the way down below the water line.

The Dimock stayed at the scene until the fog lifted, and by 3 PM headed for Boston with her now rag-tag survivors, arriving there safely around 8 PM. Telegrams were sent to inform friends and family of the survival of the passengers and crew of the wreck, and arrangements were begun to either raise the ship or salvage her. She lay in the worst possible place—the shipping lane of that route. A lantern had been hung from her exposed mast in the hopes that it would burn through the night, warning other ships.15 The Alva had been built with four airtight compartments to prevent her sinking in a collision, which did not save her, and she had been outfitted with electric lights throughout. She also boasted a powerful searchlight, yet these innovations were useless in this situation and the sailors had to rely on an old oil lantern after all.

By the 26th, reports were coming in that on the very evening of the abandonment of the vessel, it had already been stripped of its rigging, blocks, topsails, foresails and mainsail, and any boxes or trunks which had floated to the surface or had washed ashore. Any attempt to raise the craft proved impossible and on August 4, 1892, the Alva was sold, bought by a Boston firm for $3,500. Vanderbilt’s $500,000 floating palace was sold in a twenty-minute auction.16

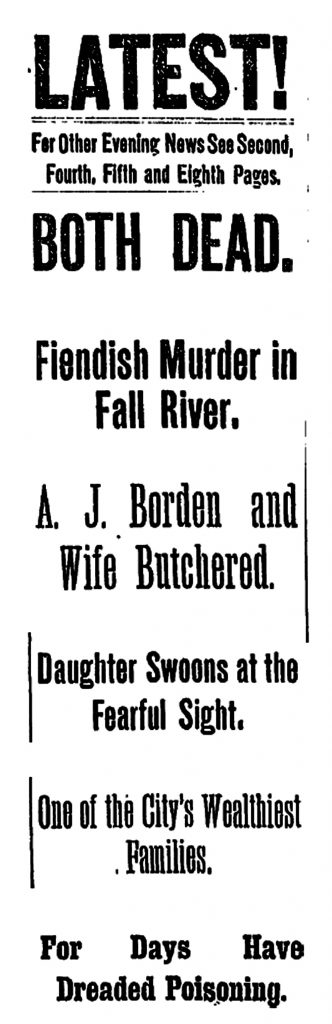

The selling of the Alva wreck shared space and headlines in the Boston Globe with a double homicide that made page one:

Both Dead

Fiendish Murder In Fall River.

A.J. Borden and Wife Butchered. 17

On the same date, buried on page 8, in the sailing and yachting news section, there is found the item describing Jay Gould’s yacht for sale for $200,000.

The next day, in the Boston Globe’s continuing coverage of the Borden murders, appeared the following information from John Morse:

It was about 6 o’clock when I got up, and had breakfast about an hour later. Then Andrew and I read the papers and we chatted until about 9 o’clock.

I am not positive as to the exact time, and it may have been only 8.45 o’clock.

While at the table I asked Andrew why he did not buy Gould’s yacht for $200,000 at which price it was advertised, and he laughed, saying what little good it would do him if he really did have it. We also talked about business.18

Morse was referring to the notice out of New York, which appeared in the Boston Globe on August 4, 1892:

Too Expensive For Gould. His Magnificent Yacht Atalanta Can Be Purchased for $200,000.

It was said yesterday in Wall st. that Jay Gould had asked the A.O. Hughes agency to sell his yacht, the Atalanta.

The story was that Mr. Gould had decided to dispose of the yacht because of the wreck of the Alva.

Mr. Hughes told a Sun reporter that on August 28, 1889, he had been commissioned to dispose of the Atalanta.

“The Atalanta,” he said, “has not been in commission since 1890. A long time ago a gentleman informed me that he wanted to buy her.

“The price set by Mr. Gould at first was $250,000. I believe the boat cost $500,000.

“On July 18 I wrote to Mr. George Gould, asking him what was the lowest figure for which his father would sell the Atalanta. The next day I received a reply that the lowest price was $200,000.

“The Alva was wrecked on July 23 [sic, the 24th]. The date of Mr. George Gould’s letter shows that the loss of Mr. Vanderbilt’s boat had nothing to do with Mr. Gould’s determination to sell the Atalanta.”

It is said that Mr. Gould has found it to be too expensive to maintain the Atalanta, even in idleness.19

By the end of the year, Jay Gould was dead. He had known he had not long to live. His physician had warned him three years previously that he had consumption and would eventually die of it, and that is probably the real reason Jay Gould put his yacht up for sale. Earlier in the year, he had packed his private train car, also named Atalanta, and along with his unmarried daughter Helen, who was his hostess and companion after her mother died in 1889, and his younger son, set out on a long journey, leaving New York to escape the cold March winds which so bothered his neuralgia. At that time, it was reported that he looked drawn, ill and gray.

Around Thanksgiving, Gould hemorrhaged and had another attack a few days later. About this time, he updated his will, adding two codicils on Monday, November 21, 1892, putting his estate in order. He knew he was passing, and his family gathered. After he died on December 2, 1892, his son, George, was in control of the fortune. George had been the steward of the Gould holdings for several years before his father’s death. George was in charge of selling the Atalanta in 1892, when the notice was published that caught the attention of John Morse on that fateful day in August, the last day of his brother-in-law Andrew’s life.

Why Morse made that comment, and why Andrew answered as he did, is anyone’s guess. But that yacht was still unsold as of May 27, 1898, when a last news item about the famous Gould yacht was published in the Boston Globe:

Recommends Forty Yachts. New Naval Auxiliary Cruiser Board Includes George Gould’s Atalanta and Astor’s Nourmahal.

The new naval auxiliary cruiser board has sent to Washington a list of 40 yachts inspected by the old board which it recommends for purchase.

Among the vessels named are George Gould’s Atalanta and John Jacob Astor’s Nourmahal, which are recommended for purchase at $100,000 each.20

The famous racing heyday of the old, dependable Atalanta was long over, but her possible new role in service to her country meant there was no shame in her reduced price tag of $100,000. Those who sailed her to victory would remember her as The Queen of the Sea, a title given her in 1886, when she ran “from Larchmont to New London, a distance of eighty nautical miles, in quicker time than it was ever covered before.” She was considered the “handsomest boat in the fleet” and as she sailed up to drop anchor after her win, amongst a harbor filled with all types and variety of crafts, with crowds cheering on the fine lawns and pushing to get a good look at her, she showed at her best, and she was beautiful.21

Afterword

In testimony, John Morse is not asked, and does not state, that he read the newspapers after he arose on August 4 at 6 AM, as he waited for Andrew in the sitting room, before breakfast. Yet some papers claim that Morse stated that at breakfast, a bit after 7 AM, he asked Andrew Borden if he would like to buy Gould’s yacht, but inexplicably, the yacht sale article was published on August 4th.

In the Boston Globe, the item fits in with other yachting news also dated August 4th. One item, “May Call At Marblehead,” gives the information that “The New York Yacht Club fleet leaves here at 11 AM today for Newport. There was a fog outside early this morning and it had not lifted at 9 o’clock, so an early start could not be made.”

This sounds like this Globe page, or parts of this page, were added to the issue after 9 AM and probably before 11 AM. It is probable that the Globe had several morning and evening editions, adding or subtracting pages, and even rearranging the front page. By 1894, with new linotype machines and the advent of typewriters, combined with a well-developed circulation system, there were “seven morning and nine evening editions . . . every new deadline gave a chance to replate with any new story or, in the absence of one, to rearrange the front page to look new.”22

We have yet to discover how Andrew Borden received his daily newspaper, but regardless, the question becomes from where did Morse get this information by 7 AM on Thursday, the 4th? This kind of conundrum begs discussion.

The segment on Morse mentioning Gould is found in the Boston Globe, the Fall River Herald and the Fall River Globe published on the 5th, all with exactly the same wording. There is no named author. It is not found in the New York Times or the Evening Standard. It is not certain if it appeared in the Providence Journal. The New York Sun is out of business, and cannot be checked for a news item about Gould’s yacht being offered up for sale.

The possibilities are narrowed to these:

1. For Morse to have read the item by 7 AM on August 4th, he had to have the paper of the 4th. His version of the paper would have included the item.

2. How did he get the paper of the 4th? Did he go out and buy it between 6 AM when he arose and when Andrew met him in the sitting room before breakfast?

3. Did they actually discuss the news item after breakfast while they were looking at the papers?

4. Was the paper delivered to the house early?

5. Was there a delivery slot in the door for mail and newspapers? If there was no slot, Morse would have to open a door to get a paper. If the paper referred to was that morning’s papers that Andrew and Morse were reading after breakfast, how did it come into the house?

6. The author of the piece made up a fictitious breakfast conversation about Gould’s yacht between Morse and Andrew Borden.

7. The Sun, or a Wall Street newspaper issued the item the previous day, and the Boston Globe picked it up. This explanation seems somewhat far-fetched, considering the wording of the notice. It begins: “It was said yesterday in Wall st.,” which does not imply a written account, by any means. It implies a rumor going around that the Sun reporter verified and printed out of New York on August 4th. By 1892, there was direct telephone communication between the New York correspondent and the Globe.23

It seems that any of that day’s issue of the Globe, could be a revised edition, causing more copies to be sold because the populace thought it looked newly issued. Also it is probable that certain items or pages were added or subtracted according to the region of distribution.

Any comments or speculation or knowledge of this mystery can be directed to the Editor in a letter or e-mail, or can be made in an open discussion format at the Lizzie Andrew Borden Society Forum, located at:

http://lizzieandrewborden.com/LBForum/index.php

Endnotes

1 “The Dead Money King,” Atlanta Constitution, 3 December 1892: 4.

2 “Millionaires and Public Opinion,” Boston Globe 10 December 1892: 4.

3 “A Pointer for Rich Men,” Atlanta Constitution 5 December 1892: 4.

4 Ibid 4.

5 “Jay Gould’s Yacht,” Atlanta Constitution 27 June 1883: 5.

6 “Rich Men Afloat,” Atlanta Constitution 29 July 1883: 3.

7 “Glimpses of Gotham,” Atlanta Constitution 31 July 1887: 2.

8 “Vanderbilt’s Alva Afloat,” Boston Globe 4 February 1887: 3.

9 “On the Delaware’s Bosom,” Boston Globe 15 October 1886: 8.

10 “Yachting By Steam,” Boston Globe 29 March 1886: 5.

11 Leonard Rebello, Lizzie Borden Past and Present (Fall River, MA: Al-Zach Press, 1999), 62.

12 “Morgan Enters Protest,” Boston Globe 17 August 1888: 5.

13 “In Light Airs,” Boston Globe 31 May 1894: 6.

14 “Right for a Sail,” Boston Globe 31 August 1896: 2.

15 “Alva Sunk,” Boston Globe 25 July 1892: 3.

16 “The Alva Sold,” Boston Globe 4 August 1892: 2.

17 Ibid 1.

18 “Twelve Cuts,” Boston Globe 5 August 1892: 4.

19 “May Call at Marblehead,” Boston Globe 4 August 1892: 8.

20 “Recommends Forty Yachts,” Boston Globe 27 May 1898: 4.

21 “Queen of the Sea,” Boston Globe 16 July 1886: 1.

22 Louis M. Lyons, Newspaper Story, One Hundred Years of the Boston Globe (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1971), 97.

23 Ibid.