by Richard Behrens

First published in April/May, 2008, Volume 5, Issue 2, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

The study of unsolved murders from the past can often teach us about the people and culture of another time and place. Reading about Jack the Ripper opens up a window into the murky underworld of Victorian London; Lizzie Borden reveals much about the genteel culture and private living conditions of industrial New England society; even the assassination of JFK, now so distant in time, resurrects the political paranoia of the Cold War era and gives a glimpse of what America had been like on the other side of the 1960s.

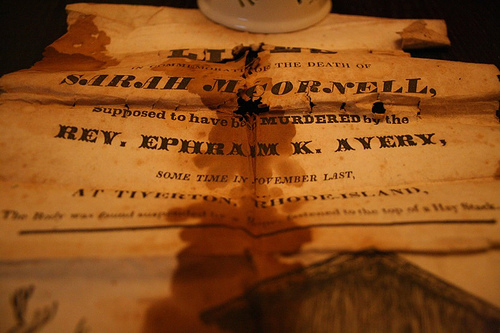

It is now one hundred and seventy-five years since Sarah Cornell, a thirty-year old weaver in a Massachusetts cotton mill, was found strangled to death on the edge of a farm near Fall River in December of 1832. The physical evidence at the crime scene, plus incriminating but unsigned letters found among Sarah’s possessions, led to the arrest of the Reverend Ephraim Kingsbury Avery, a Bristol, Rhode Island Episcopal Methodist minister. The resulting trial, besides being a great newspaper sensation, was, up until that point, the longest, and most complex in American history. Like that other great Fall River mystery, the Borden Murders of 1892, the case remains unsolved and a matter of great controversy.

However, the seasoned Lizzie Borden student would be quite surprised to find in the Sarah Cornell story a very different Fall River than the one depicted in the newspaper accounts, police reports, and trial transcripts of the Borden Affair of 1892. Here, we are transported to a more primitive society, one more rural and driven by religious factions, a world being reshaped by the industrial revolution, but not quite close to the great industrial nations that would build the Titanic and the Panama Canal. The Bristol/Tiverton/Fall River axis upon which the story pivots is indeed a scene filled with familiar elements: present are the Borden and the Durfee families, the worshippers at the First Congregational Church and the shoppers going about their afternoon business on South Main Street. But this is not Lizzie’s Fall River; it is the town of Andrew Borden’s childhood, the Fall River of David Anthony and Oliver Chace (two of the great early mill owners), where no street cars clatter along the cobblestones, no telephones are to be had at the corner stables to summon the police, and you can converse with many a man who still remembers the Revolutionary War. The world of Sarah Cornell and the Reverend Ephraim Avery was as different from Lizzie’s as our world today is different from the days before the Cold War.

Sarah Cornell died just a few short years after Fall River had given birth to its textile industry, an enterprise that would make the city one of the country’s most important manufacturing centers and establish a vast economy built upon the labor of young women like Sarah. The bulk of that industry and wealth was still in the future at the time at her death, but a study of the complex social web in which she had become enmeshed, the religious community in which she struggled for approval and found nothing but condemnation, the society that scorned her for her amoral lifestyle and choices, the factory system that swallowed her up as a mere cog in the wheel of labor, has a lot to teach us about New England’s deep roots and our own collective cultural history.

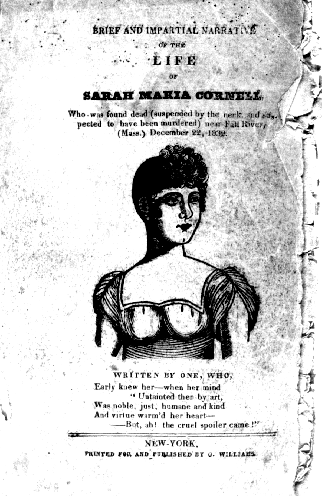

Sarah Cornell was born on May 3, 1802, into an established Connecticut family. Her grandfather had been a successful paper manufacturer and Sarah would have grown up in a genteel affluent environment if her mother had not tragically run off with a worker from her father’s mill. Fallen out of favor with the family, and ultimately abandoned by her husband, Sarah’s mother inherited only enough money on which to survive and spent many years in a furtive rambling existence with her daughter. Young Sarah was first trained as a tailor, but soon had become a weaver working in various factories. The girl had been condemned to the life of a skilled laborer in the mills of New England, a consequence of her mother’s exile from their families’ wealth.

(NY: Printed for and published by G. Williams, 1833).

To make the situation worse, Sarah seems to have grown fond of misconduct and often was the subject of much scandalous rumor about her sexual proclivities. There is no doubt in Sarah’s own letters and confessions that she saw herself as a bad woman. Musing upon the death of a gentle black servant, she wrote: “Sometimes I think why I am spared, perhaps it is to commit more sin” (31). No doubt, in today’s day and age, she would be viewed as a girl whose poor choices led to complications and confusions; but in Sarah’s age, ruled by rigid laws and religious judgment, such misconduct was enough to make her an outcast from society.

While staying in Providence and working as a weaver, Sarah got into trouble over some clothing that she took on credit from a tailor and then never paid for, a controversy that seemed to have cemented her reputation as a thief and a fallen woman. Although accounts of her activities are often contradictory and their truth suspect, Sarah was clearly a reckless youth who sank deeper into trouble no matter how far she fled. She moved from town to town, sometimes changing her name and inventing a past for herself to start life anew, but bad luck followed her. Sometimes it was the simple fact that she was seen walking with a strange man after work that strengthened her reputation for promiscuity.

Soon she was looking to make amends and return to the fold of her family. “God in his mercy has shown me the depravity of my own wicked heart” (35), Sarah wrote to her mother and sister in an attempt to reconcile with them and to throw herself under the protective umbrella of religion. She became a member of the Congregational Church, but her later shift to the Episcopal Methodist Church may have been prompted by the appealing Methodist belief that all can be saved, not just the elite, and that salvation had more to do with deeds and faith than the randomness of being born into a well-positioned family.

Sarah was by now a poor laborer with a sinful reputation, so the Methodist Church may have seemed a logical haven for her. Their tent meeting culture, modeled after the tribes of Israel wandering in the wilderness, must had struck a chord in the mill workers whose survival depended upon a migration from one town to another, drifting about as factories burned to the ground, and labor disputes forced unemployment.

Sarah’s own assessment of the four-day-long tent meetings where ministers gave their impassioned impromptu sermons was that all the Methodists should be “as strangers and pilgrims having no continuing city or abiding place, but seek one to come” (40). Clearly, her spiritual yearnings were authentic, and, in the Methodist Church, she found the closest she would ever come to a central home and a self-identity. But sadly, this safe haven proved to have no lasting value for her.

After more accusations of being in the company of strange men—on one occasion taking up lodgings in a hotel together—Sarah took flight to Lowell, Massachusetts—at that time a great industrial center—looking to reinvent her life yet again. When she arrived there in May, 1828, she was armed this time with a certificate of membership in the Methodist Church, a piece of paper that, because of her poor moral reputation, meant the difference between work and starvation.

Daily life in the Lowell mills started for Sarah, and many other young women like her, at five in the morning and often lasted until six at night. They were paid by the piece, not by the hour, and the girls had to live in boarding houses owned by the factory. Condemned to such a life and hounded by rumors and whispered stories of her sinful past, Sarah decided to jump once more to another profession, one that would put her squarely into the arena of her Church and perhaps redemption in the eyes of her fellow Methodists: she applied for a job as a domestic in the home of the Reverend Ephraim Avery.

Ephraim Kingsbury Avery was a young man from Connecticut, thirty-four years old at the time that Sarah Cornell first knocked on his door in 1830. A decidedly handsome man with a sensuous mouth (a trait that was much played up by his detractors during and after the trial as proof of his libertine nature), he was originally slated to be a man of medicine, but followed a calling into the Methodist Church. He carried about with him his own baggage of scandal, mostly a zealous and rash preoccupation in reporting the ill conduct of members of his flock. On a few occasions, he had spoken out against fellow Methodists and what he perceived to be their bad behavior and morals. At the time, the hierarchy of the Methodist Church was ordered into societies, assemblies, and conferences—creating a culture in which the ranking ministers could ensure a person a stable life by awarding them a certificate of good standing within the church. A denial of such a certificate would result in banishment and often the inability to find employment.

Avery’s rise in the community and the New England Methodist Conference contains several interesting revelations about the changing dynamics of New England society at the time. It was a period of vast cultural and economic expansion and it was inevitable that the old Protestant religious order that had pioneered life in New England, and had served as a fabric of society for so long, was starting to respond to the rising phenomenon of modern capitalism and the impositions it made upon the lives of ordinary people who were destined to work the factories. The Reverend Avery’s subsequent unrelenting, almost paranoid, judgment of Sarah Cornell is representative of the avidity of the old order reacting to the changing conditions of modern life, where wage labor and ownership of property was forging a new culture and a new way of responding to the world.

Interestingly enough, the Methodists first laid down their presence in Fall River by 1827 with the organizing of their first church there. The Methodists were a relative newcomer on the scene, and planted themselves down in the midst of the factory-owning Congregationalists. The Methodists came across as anti-intellectual and non-elitist. The value of the minister seemed more in his ability to spontaneously sway a crowd through impromptu sermons and crank up the level of energy in a tent meeting, rather than in his learned study and integration into the local business community. Clearly, in the meeting of the mill girl and the Reverend, the two conflicting halves of New England’s emerging new order were headed for a confrontation. This may explain the severity of the passions that the Methodists and the Industrialists exhibited towards one another in the long ordeal of Avery’s capture and trial. In this way, Sarah’s death was to ignite an eruption of hidden social, political, and religious forces that were in stressful conflict within the community.

Sarah only worked for Avery for a short time (it was rumored that the Reverend’s wife detected an attraction between the two and dismissed the poor girl unfairly), then went back to the mills, but she persisted in attempting to get good references from him. The Reverend’s stubborn need to discredit the character of those he considered to be amoral created a tension between them, and a struggle of wills became more entangled as time went on.

When Sarah asked Avery to supply her with a certificate, he insisted on an open statement of her sinful behavior. She readily admitted to illicit sexual activity with several men, but she could have been lying to impress Avery with her willingness to repent. He eventually gave her a certificate in good faith, but then proceeded to initiate a church trial against her. Shortly after, Sarah showed up at a doctor’s office diagnosed with a venereal disease and then left town, taking Avery’s prized certificate with her.

As Sarah traveled about the state trying to secure employment, she kept presenting the document that would be her only hope to reintegrate herself into her Methodist community, but Avery never hesitated to inform any inquiring minister of Sarah’s ill character and evil past. When Sarah wrote him letters of confession, Avery renewed her certificate, only to denounce her the next day because he had uncovered a falsehood.

Having been excluded from Methodist circles by Avery’s persistent outcries against her, Sarah eventually took refuge at her sister’s home in Woodstock, Connecticut where her brother-in-law took her on in his shop as a seamstress and office manager. She had been welcomed into her new church but was hounded by the thought of the Reverend Avery having her letters of confession, documents that he could use to destroy her reputation at any moment. In fact, Sarah posted several letters to Bristol, Rhode Island, where Avery now lived as a minister. While it cannot be proven that she was writing to him, it does seem likely, since she knew no one else in Bristol, she was negotiating with him for the letters, and was possibly arranging for a face-to-face encounter at an August tent meeting of the Methodists in Thompson, Connecticut.

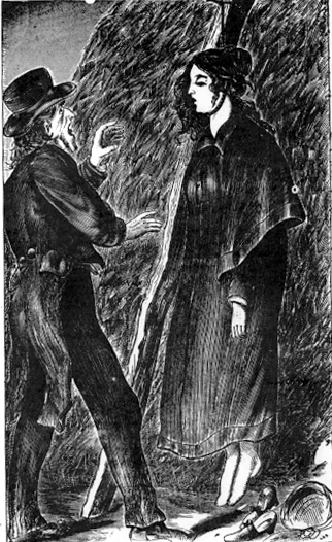

At the meeting, Avery seemed determined to get Sarah ejected from the grounds, but according to Sarah herself, he arranged to meet her in the forest near the camp grounds where he traded sexual intercourse with her in exchange for the letters of confession. Although great pains were taken at Avery’s murder trial to show that he could not possibly have slipped off during that evening to meet with Sarah, there is no doubt that several months later she was known to be pregnant.

At the suggestion of a lawyer, Sarah moved to Fall River ostensibly to be close to Avery’s home in Bristol so she could negotiate support from him. She obtained employment in the Fall River Manufactory run by David Anthony, and, despite her pregnancy and bouts of sickness, held onto the job. Sarah bravely approached Avery and begged him not to destroy her in Fall River as he had done in Lowell and elsewhere. Avery’s response was typical of his consistently heartless attitude towards the poor girl, that he had done nothing to destroy her—she had destroyed herself.

The next evening, October 20, 1832, Avery disappeared after a Methodist meeting for an hour, later claiming that he had been at some stables, but Sarah later confessed that Avery had met with her to give her references to Thomas Wilbur, a South Main Street doctor. Dr. Wilbur, who examined the girl, was horrified to learn that Avery (or at least as Sarah told the story) had instructed her to take 30 drops of oil of tansy to induce the abortion, a dose that certainly would have proven deadly. In short, if Sarah is to be believed, Avery was trying to get Sarah to take a fatal overdose.

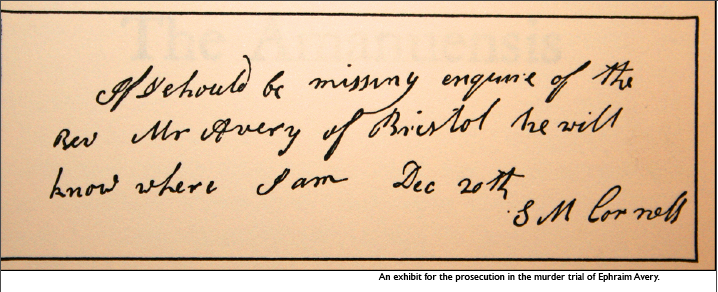

Throughout November and December, Sarah allegedly negotiated with Avery via secret letters. The ones that were found in Sarah’s possession after her death, unsigned and in a hand never determined to belong to the Minster, clearly were about arranging for a meeting in Fall River on December 20, 1832. Indeed, on that day, Sarah left her job at the Mill early, ate a quiet supper in the rooming house where she was saying, and then wrote a penciled note before taking off into the night: “If I should be missing enquire of the Rev Mr Avery of Bristol he will know where I am Dec 20th S M Cornell” (73).

The next morning, Sarah was found dead, hanging in a haystack just outside of Fall River.

Sarah Cornell’s body was discovered on the morning of Friday, December 21, 1832, at nine o’clock in the morning on the Richard Durfee farm in Tiverton, not far from the Fall River border. She was suspended from a pole attached to the roof of a haystack, her cloak fastened about her with her hands inside, a significant fact that was later to be pointed out by Avery’s prosecutors. Elihu Hicks, the Tiverton coroner, gathered a jury of six men to observe the body, and after she was identified as a girl from the weaving room of the Fall River Manufactory, Dr. Wilbur was called upon. The Fall River doctor promptly came to the circumstantial conclusion that Sarah had killed herself because of the betrayal of the Reverend Avery, the man who had fathered her unborn child. The coroner’s jury gained access to Sarah’s personal possessions at her boarding house, including letters found in a bandbox that clearly showed she had been negotiating a meeting with an unnamed person (known only in the letters as B.H., which were the initials of Avery’s niece, Betsey Hill), and promptly came to the conclusion that she had committed suicide over her pregnancy and betrayal by Avery.

From the start, tensions between different political and religious factions charged the case with high drama. The Methodists refused to bury Sarah since she had not been on good report with the church, and, further, a letter of resignation from the church in her handwriting had been found in her bandbox. The Reverend Ira Bidwell, a Fall River Methodist minister who had been called to the scene of the crime, immediately ran off to Bristol to tip off Avery that he was about to get into serious trouble. Reverend Orin Fowler of Fall River’s First Congregational Church took on the duty of burying Sarah, possibly at the request of her last employer, David Anthony, a Congregationalist. The people of Fall River were now experiencing a sense of empathetic identification with the poor young girl who had died over the machinations of a Rhode Island Minister who had done her wrong, and was, almost as serious, a Methodist.

The coroner’s verdict and Sarah’s funeral on Saturday, December 22, were a bit premature, since it was after the services that the penciled note she had written the night of her death implicating Avery was found. It was further rumored that her body showed bruises and other signs of abuse, and that the clove hitch knot that had been tied around her neck could not possibly have resulted in a self-inflicted hanging. The cry of “Murder” was immediately raised.

Stirred with the conviction of foul play, the coroner’s jury was immediately dismissed—two of the men were not landowners, a technicality that invalidated the verdict—and the body was exhumed for re-examination. While Dr. Wilbur worked hard to obtain a legal judgment of murder against Avery, the Reverend Bidwell was in Bristol warning Reverend Avery that trouble was brewing. After a bizarre cat-and-mouse game in which two Fall River men traveled to Rhode Island to obtain an arrest warrant for Avery at a time when the murder did not yet legally exist, the Reverend was finally arrested on the evening of Sunday, December 23.

Fall River, Massachusetts.

Fall River came together as a community during the days immediately following the discovery of Sarah’s body. The crime had been committed outside their jurisdiction, in Tiverton, and Avery was to appear before a court in Bristol where he had been arrested, so Fall River, determined to see that justice be done, had formed a committee of vigilance and a committee of investigation that was to aid the Rhode Island officials in whatever way they could. While the case against Avery seemed open and shut, largely due to Sarah’s own confessions to the Reverend Bidwell and Doctor Wilbur, as well as the content of the letters found in her possession, the gap between the Fall River Congregationalists and the Rhode Island Methodists was widening. There was also a decidedly anti-Masonic atmosphere to the whole business since certain members of the Fall River committee were staunch anti-Masons, and associated the Methodists with that fraternal community. Clearly, the death of Sarah Cornell and the Reverend Avery’s association with it, as unproven as it was at the time, was causing the internal stresses between Fall River’s industrial and religious factions to bubble to the surface.

On Christmas Day, the Fall River committee boarded the King Philip to be ferried to Bristol to demand the release into their custody of the Reverend Avery, whom they were determined to have examined in Tiverton. The engineer of the ferry was John Orswell, a man who had delivered to Sarah one of the letters, in an unknown hand, which had proposed a meeting in Fall River. Orswell claimed that the letter had been given to him by the Reverend Avery to deliver into the hands of Sarah Cornell. If such a connection could be proved, it would seem a simple case that only needed its day in court to see Avery hanging from a gallows.

The Fall River men soon found that truth and justice often can take a back seat to political and religious factions. When Justice Howe of Bristol insisted on keeping the case in his jurisdiction, the committee marched to Avery’s home where he had been allowed by the court to reside, towing Orswell behind them, and confronted the Reverend during a tense scene that almost turned into mob violence. Avery, after being identified by Orswell as the stranger who gave him the letter, put on his spectacles and asked Orswell again if he looked familiar.

“Sir,” said the Ferryman, “your glasses do not alter the features of your face” (26).

The Fall River Committee eventually retired to their hometown, empty-handed. Avery was to stand before a court in Bristol.

Reverend Avery’s examination began before Rhode Island Justices John Howe and Levy Haile, with the Reverend himself reading from a carefully prepared statement. From the very beginning, it was clear that his defense was based upon two tactics, the first being the denunciation of Sarah Cornell as a woman of evil disposition, no better than a whore, and someone who had used him as an innocent scapegoat in her boundless machinations. The court was being asked to interpret all the testimony and evidence against the defendant in the light of Sarah’s sinful existence which, contrasted against Avery’s impeccable reputation and serious concern for the moral correctness of the Methodist society under his protection, seemed to be conclusive proof of his innocence. In short, it was Sarah Cornell, the victim, who was now on trial.

Secondly, the defense was determined to prove that all the evidence against Avery—the letters found in Sarah’s possession, the confessions she made to confidants about her carnal relations with Avery, his role in her pregnancy, and any testimony dealing with the Reverend’s whereabouts on December 20—was circumstantial and based on the clever lies of a very desperate woman and her Congregational supporters. All in all, Avery hoped to prove that he was a righteous servant of his flock, and Sarah was a fallen woman who could not be believed, even in death.

Avery’s opening statement also provided his own explanation for his whereabouts on December 20 during the crucial hours in question. Claiming to have been curious about a coal mine on the island between Bristol and Fall River where he could obtain cheap heating for his church, the Reverend decided to ramble over some of the island’s countryside, a hobby that many of his friends testified he was very fond of, and to negotiate a coal purchase. Having crossed over to the island on the Bristol ferry, he headed towards the mines, only to discover that there was no coal to be had, so he took off towards the house of a friend—which he could not find in the descending darkness of winter. He claimed to have returned to the ferry, a location some nine miles or so from the site of Sarah’s death, at nine o’clock in the evening, approximately around the time the coroner fixed Sarah’s death, which was a strong argument for his innocence. He absolutely denied having crossed the stone bridge into Fall River at any time.

The Reverend, however, had no definitive witnesses that placed him on the island besides the ferry man at Bristol. The hearing and the second trial later that year included a parade of witnesses who claimed to have seen the Reverend, or someone who looked like a Methodist minister, at various points of the island, at the stone bridge, and even at a tavern in Fall River, closer to the time of the murder. Avery’s stroll across the island is just as elusive and frustrating to fathom as Lizzie Borden’s own sworn whereabouts at the time of her father’s murder.

During the course of the hearing, the defense attempted, through objections, to prevent the jury from hearing any testimony that implicated Avery in Sarah’s pregnancy, including second-hand accounts of her own confessions. Persuading the court that Sarah’s words were hearsay and not sworn testimony or deathbed confessions, the defense unexpectedly barred the prosecution from pursing any direct quotes. As a result, Dr. Wilbur testified as to Sarah’s physical condition of pregnancy, but he was prevented from quoting her that Avery had been the father. Likewise, Sarah’s brother-in-law was prevented from telling the jury how she had told him in confidence all about Avery’s seductions and carnal blackmail. Even when various Methodists were called to remember confessionals from Sarah’s own letters, they were not allowed to quote from memory because it was judged that nothing could be proved without producing the letters themselves, which no longer existed. This was potentially a killing blow to the prosecution, although they tried their best to get the court to allow the testimony.

The hearing ended after fourteen days of testimony with a verdict in favor of Avery. Justice Howe delivered his decision to the shock of the angry people of Fall River and those who had sympathy with the dead mill girl. He did not believe the signs of abuse on her body were anything more than an attempt at a self-induced abortion, and even questioned if a clove hitch knot had been used on the cord that strangled her—a clove hitch would have ruled out suicide. In regard to the unsigned letters, the Thompson meeting, and other occasions where Avery could have sneaked off to meet with Sarah, the Justice put significant weight on the number of Methodist ministers who were paraded before the court to account for Avery’s whereabouts on crucial dates. Howe found the timetables, as defined by the Methodists, unimpeachable.

Not only did Howe find Avery innocent of the charges, but he also summarily decried Sarah Cornell as a girl addicted to every imaginable vice, and no better than a prostitute. Most shockingly of all was his declaration that even if Avery had met Sarah in Tiverton that evening, he most likely would have just given her a cautionary speech, which the Justice conjured from his own dramatic imagination for the sake of the court. In short, the Justice could believe that Avery lied about meeting her, but it was beyond all doubt that such a man could not have murdered her. When Justice Haile concurred, Reverend Avery was set free.

A storm erupted. Newspapers cried out for justice, and in Fall River, David Anthony, called a meeting of seven hundred people in the vestry of the Congregational Church to determine how best to get a new warrant issued for Avery’s arrest and re-trial before the Supreme Court of Rhode Island. The Fall River Committee of Investigation, in turn, claimed to have come up with new evidence—a letter that Sarah Cornell had written describing her relationship with Avery and her attempts to meet with him. With the prospect of such damning evidence being introduced to a court without objection from the defense, Harvey Harnden, the deputy sheriff of Bristol County and a committee member, set off on a dramatic chase across three states to track down Reverend Avery, who had secretly slipped away to a hiding place in New Hampshire.

Tracking his prey through Rhode Island and Boston, Harnden, who was very familiar with the pursuit of criminals, canvassed the taverns where Avery’s carriage had halted, and visited the homes of the Methodist ministers, whom he bullied with threats of legal action if they did not give him information as to Avery’s whereabouts. Harnden eventually cornered Avery in his New Hampshire hideout and stormed the building, finding the Reverend cowered in an upstairs bedroom. Avery was brought back to Rhode Island where Harnden was dismayed to find that, although the Governor had posted a reward of three hundred dollars for the capture of the accused man, the offer had been posted after the capture. The deputy sheriff walked off with a mere reimbursement of his travel expenses. One new report announced that Harnden had “commenced the pursuit for the acquisition of the glory it might produce; he enacted the part of a hero, and let the trophies of the hero be his reward” (127). This did nothing but further the resentment against Avery, and hardened the shell of support and protection forming around him from his fellow Methodists.

Avery was now back in custody in the hostile territory of Tiverton, and swarmed about by a hostile Fall River crowd. He anxiously awaited a hearing before the Rhode Island Supreme Court. A defense dream team headed by Jeremiah Mason, a lawyer friend of Daniel Webster’s, and the collective resources of the New England Methodist Conference, was quickly assembled. The tempers and fevered antagonisms between all the different religious and social strata of New England society had reached a high pitch. The trial promised to be more dramatic, passionate, and desperate than the Bristol hearing.

In a bizarre but significant footnote to the preparation for the new trial, Sarah Cornell’s body was once more exhumed, more than a month after her death, and found to show signs of an attempted abortion and/or sexual abuse.

Reverend Avery’s second trial began on Monday, May 6, 1833, at the 18th century Colony House, in Newport. This time, big guns were pulled out of the state’s pockets to fill the prosecution, including Rhode Island Attorney General Albert C. Greene and former attorney general Dutee J. Pearce, who actually gave up his seat in Congress to prosecute the case. Over a hundred candidates were screened over three days to create a jury of twelve—such was the mounting dramatic pitch of the trial. By the end of the trial, which, according to Fall River historian Henry Fenner, lasted twenty-one court days, 238 witnesses were called to testify.

Avery listened to the indictment brought against him, which included that he had been “moved and seduced by the instigation of the devil” (136)—a grim reminder to a modern reader that we are dealing with a very specific New England culture, one still rooted in the blurred boundary between church and state.

The prosecution’s case had a bumpy start as the jury was denied the right to retain paper and pencil for note taking. This was a denial that worked in favor of the defense, since the trial, which lasted a month, was so long and complex—the 1830s were a time when trials were spectacular if they lasted a week—that the conflicting facts, dates, times, and places that were paraded before the empaneled jurors became, as the weeks went on, a confused jumble.

The main strategy of the prosecution was to place the Reverend Avery in the right places at the right times with the right motives. They needed to prove that Avery had maintained a relationship with Sarah Cornell, had been at the Thompson tent meeting where she allegedly had become impregnated, was in Fall River when the letters to her had been mailed, and had lied about his trek over the Island, making it plausible that he had traveled into Fall River on the evening of December 20. The second thrust of this attack was to finally place before the jury Sarah Cornell’s own confessions to her doctor and family that Avery was the father of her child. These two combined would toll the Reverend’s doom.

Much rested upon the condition of the body during the initial examination and upon subsequent exhumations. The fact that the neck had shown only one set of marks, due to the strangulation from the cord and not from any assault by Avery, suggested suicide, while the bruises and discolorations on her abdomen and the fecal matter upon her undergarments, suggested that at one point in her ordeal she had been lying upon the ground suffering some form of abuse. However, sexual modesty prevailed when the four women who had been charged by the Reverend Orin Fowler to prepare Sarah for burial, were called to testify to Sarah’s physical condition and found that they could not speak plainly about the dead woman’s body. One witness kept insisting that Sarah had been “dreadfully abused” (144), and would not shake her chosen description even when pressed by the court to be more accurate. In the end, their testimony was considered lacking in the expertise that would have been present in the report of a more expert medical man or coroner.

Further, some testimony as to the condition of the body was based on the examination thirty-eight days after her death, when her decomposed body had been exhumed for the second time. These less than optimal forensic conditions practically disqualified all talk of bruises, which could have been caused by blood settling after death, and any physical evidence of rape or attempted abortion.

As in the initial hearing in Bristol, witnesses were produced to prove that Avery had mailed Sarah the letters arranging a rendezvous at the Fall Meeting, that Avery had crossed the stone bridge to Fall River on the afternoon of December 20, and that Sarah Cornell was not in a suicidal mood in the last days of her life. Even the justices from the Bristol hearing were called as witnesses to prove the inadequacies of their own legal proceedings. Much of the trial seemed a rehash of the previous one, but with a dramatic increase of the emotional ante.

As predicted, when Dr. Wilbur was asked about Sarah’s confession to him that Avery was the father of her child, the defense objected that Sarah’s words were hearsay, and not sworn testimony or a deathbed confession, and therefore inadmissible. After several fumbled attempts to get Sarah’s words to the doctor before the jury, the prosecution struck upon a clever plan. They noted that the doctor had been given a statement that had been published in a newspaper called the Microcosm about Sarah’s accusations. Claiming that the statement, as published in the newspaper, differed from the statement he had made in court, the prosecution requested that the newspaper copy be entered into the trial as evidence, thereby getting it in front of the jury. The plan failed when it was determined by the court that the two statements did not significantly differ.

The defense team attempted to prove that Sarah was a manipulative and troubled woman, often unstable and suicidal. Doctor William Graves of Lowell testified as to Sarah’s mental condition: “I was almost inclined to think she was insane” (163). However, the defense quickly pointed out that Dr. Graves had been the Reverend Avery’s personal physician. Sarah’s promiscuity and alleged history of venereal disease were put on display, and an unproven tale was related by a tavern keeper that once Sarah had extorted money from a man by pretending that a blanket wrapped under her clothing was his unborn child, proving a tendency towards desperation and deception.

The defense went on to claim the forensic evidence was insufficient to prove murder, that all of the testimony of a stranger who looked like a minister on the island during the murder could be discounted, and that Avery’s whereabouts could not be proven. A medical expert testified that the fetus found in Sarah’s body could have been too old for it to have been conceived during the Thompson Methodist meeting.

Another moment of sexual modesty occurred when a woman who had seen Sarah bathing at the Thompson meeting could not bring herself to describe the state of her breasts, whether or not they were in a swollen state from pregnancy: “her countenance looked as though she was in a state of pregnancy,” claimed the Methodist woman (172). The lawyer examining her broke all decorum and insisted upon a description of the state of her “bosom.” All the woman could insist was, “I noticed nothing but her countenance.” After much harassing from the lawyers, she finally broke down and said, “Her bosoms appeared rather full.” A few moments later, when asked to clarify her description, the woman, shocked and impatient, withdrew her statement, claiming she did not know if Sarah’s bosoms were fuller than usual. From the prosecution’s point of view, this was a far cry from a valid medical opinion on pregnancy.

More Methodist witnesses from the Thompson meeting were produced to account for almost every second of Reverend Avery’s time there. The tension between the Methodists and the Congregationalists was increasing as more of Avery’s kind flocked to his defense. The Methodists, in turn, seemed rather paranoid that the Fall River Committee was no better than a crazy mob giving in to hysteria, much like the Salem Witch Trials of 1692.

At the defense’s summation, Mason emphasized that not only was all the evidence circumstantial, but that it could not even be proven that a murder had taken place, which led to another moment shocking to the modern reader: Mason declared that suicide “may almost be called the natural death of the prostitute” (202), and that “if you were to seek for some of the vilest monsters in wickedness and depravity, you would find them in the female form” (201-202). As an illustration, he painstakingly laid out all the vices in Sarah’s short life—her venereal disease, promiscuity, and unwedded pregnancy—as proof that the “termination of [her] career” (202) would naturally be suicide. The Reverend Avery, on the other hand, had no history of depravity or murderous tendency. How could such a righteous man take such a huge leap from his pious self to deranged killer? It was more likely that Sarah Cornell framed him.

Mason took Fall River to task, painting a portrait of that town as run by a mob of vigilantes who would rather fanatically pursue a man to the gallows than carry out a reasoned and dispassionate search for the truth. He pointed to the large number of pamphlets and newspaper accounts that shouted Avery’s guilt and made the claim that an unbiased trial was, by this stage, almost impossible to achieve.

This last charge was addressed in the summation by Attorney General Greene who defended the actions of the Fall River citizens, emphasizing that they were not driven by any anti-Methodist passions or a blind belief in Avery’s guilt. Respectable citizens and an experienced lawyer, who had performed their civic duties in the face of the tragedy, guided them. Greene concluded that none of the flimsy medical testimony could sustain a conclusion of suicide, that it was nearly impossible for witnesses to have remembered Avery’s movements on certain days down to the last minute, and that the final note found in Sarah’s bandbox explaining that the Reverend Avery would know of her whereabouts in case of her disappearance were all proof that she had met with him in Fall River at the hour of her death.

Finally, after twenty-one days in court, a short deliberation of the jury came back with a Not Guilty judgment and the Reverend Ephraim Avery walked out of the Newport courtroom a free man.

A third trial followed shortly thereafter—the church trial by the New England Methodist Conference. Essentially a formality, the proceedings did nothing more than provide seven Methodist ministers the chance to review the trial transcript that had been liberally published in various editions in newspapers around the country. Predictably, they dismissed the witnesses for the prosecution as unreliable, chalked up the work of the Fall River Committee as the hysteria of a lynch mob, and criticized a climate in which “shadows become embodied into substantial forms, dreams are changed into realities, and vague impressions become known and vivid conceptions” (215). The biggest ammunition on their side was not their own investigations or judgments, but the verdicts of the two previous trials. The Reverend was quickly cleared of all charges within his own Church.

However, his expectations that he could return to a quiet life as a Methodist minister was shattered when a visit to a Boston shop resulted in his being surrounded by close to five hundred angry citizens. Newspaper campaigns were waged against him, especially by the Rhode Island Republican where an anonymous journalist named Proteus accused the defense team of conspiracy and jury tampering. Other newspapers followed suit with attacks and cries for justice. Proteus continued to attack the minister as the year 1833 progressed, even pursuing his own form of investigative journalism, at times claiming to have dug up fresh incriminating evidence.

Like the more infamous Fall River accused murderess Lizzie Borden, the Reverend Avery was subject to the wicked barbs of child rhymes such as “He killed the mother—then the child;/What a wicked man was he!/ The Devil helped him all the while:/How wicked he must be” (220). As if such an association with the Devil wasn’t enough, the songs went as far as to cry out for belated justice: “Hang him, hang him on a tree/Tie around him Avery’s knot/Forever let him hanged be/And never be forgot” (220).

Some in the city of Fall River even hung several effigies of Avery in public, one of which was torn down and dragged through the streets, followed by a screaming mob that reportedly numbered in the hundreds. At particular sermons, Avery was booed, and more than a few times, threatened physically by a hostile crowd. Even Lizzie Borden, who suffered a bitter cold relationship with the people Fall River in the wake of her acquittal, did not receive such violent ill treatment.

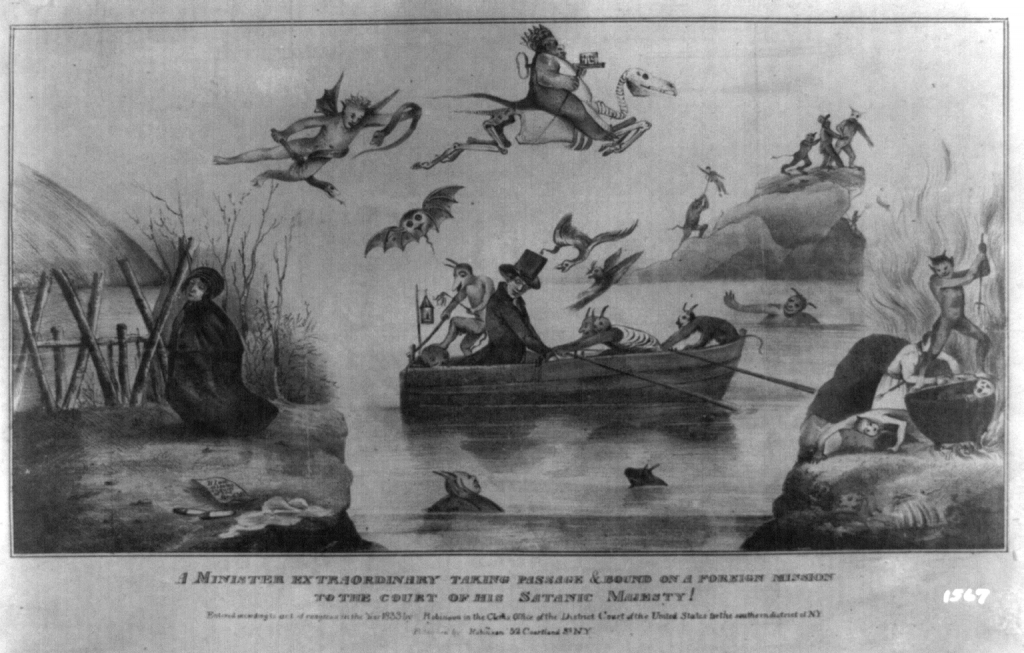

It wasn’t long before the saga of Sarah Cornell’s death reached the public through artistic outlets. In September, a play opened in Newport, Rhode Island called The Factory Girl, Or, The Fall River Murder. A play with a similar title opened in Richmond Hill, New York and soon the story of Sarah’s murder had been published as a book: Fall River, An Authentic Narrative by Catherine Williams (1833). These works were indicative of the growing anger and resentment against the Methodist religion that was replacing specific personal anger toward Avery. Strong public criticism was growing towards this Church that had an nonelected governing body ruling over people with laws that were antithetical to the Constitutional freedom of American citizens. Newspapers shouted that the Methodists were not content with merely subverting American justice, but were ambitious enough to wield political influence for the promulgation of their own ideology. Uncomfortably enough, this situation mirrors today’s climate with the Christian Right Wing and their powerful influence in Washington being counter-balanced by secular critics who profess that such religious extremism is incompatible with a free society.

The storm finally broke with Avery’s publication of his own defense, Vindication of the Result of the Trial of Reverend Ephraim K. Avery, etc. (1834), a collaboration with the Methodist Church to clear both the Reverend and the Church Conference of all guilt or charges of conspiracy. However, Avery’s position in the church was permanently compromised, and the Reverend ended his days in Ohio working as a farmer.

The story of the death of Sarah Cornell and the trial of Reverend Ephraim Avery is a fascinating and richly detailed one, and for those who are addicted to studying such matters, an unsolved mystery of great complexity. In fact, it is not even clear if a murder took place, and in a review of the newspaper accounts, trial transcripts, and subsequent books written about the affair, a bizarre puzzle appears that is as compelling and interesting as the Borden Murders of 1892. In both cases, there were sensational murder trials that ultimately crashed upon the shoals of circumstantial evidence and bungled forensics. Both cases ended in an acquittal of a defendant that many people thought to be obviously guilty, and both of the accused were denied a settled and guilt-free life in the aftermath.

However, the most startling picture to emerge from a careful study of the Cornell/Avery case is how removed in time those events now seem, and how different the world of 1832 is compared to even the nearly-modern industrial world in which Lizzie Borden lived. It is very likely that Lizzie would have heard about Sarah’s death, although it was six decades before her own ordeal. For obvious reasons, Lizzie may have identified more strongly with the Reverend Avery’s struggle to prove his own innocence, but for all those years that Lizzie lived in Maplecroft on the Hill, she could have strolled over to Oak Grove to visit Sarah in her final resting place. Perhaps Lizzie, on a summer’s afternoon, after a short visit to her family plot, could have wandered amidst the winding paths between the rolling hills, manicured lawns, and carpets of stones to see Sarah, even out of plain curiosity. It’s possible Lizzie knew little or nothing about the events of 1832-34, but in the wake of her own tragedy, she may have been curious about Fall River’s most famous other unsolved murder.

Sarah Cornell is on Whitethorn Path, just a short walk from Lizzie’s own plot. The grave marker is severely weathered and almost unreadable, but she is there forever in Fall River, amongst the graves of those Congregationalists who were the only respectable men and women who gave her unconditional community support, although, tragically, she did not live to enjoy it.

Works Cited:

Champlin, Kenneth M. History of the First Congregational Church & Fall River, Massachusetts: The Early Years 1699-1838. Published by the First Congregational Church of Fall River, Inc., 2003.

Fenner, Henry M. History of Fall River. NY: F.T, Smiley Publishing Company, 1906

Kasserman, David Richard. Fall River Outrage: Life, Murder, and Justice in Early Industrial New England. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986.